Franziska zu Reventlow, The Guesthouse

at the Sign of the Teetering Globe, Trans. by James J. Conway, Rixdorf Editions, 2017. [1917.]

In 1917, the world appears to be

tilting on its axis. Accustomed certainties are no more, alliances

are forged and just as soon abandoned. In the first of seven

thematically related stories, we meet reform-minded German eccentric

Hieronymus Edelmann on a Spanish island, where he leads a crocodile

around on a leash and lures his compatriots to a precarious

guesthouse. His motives are opaque, but one of his schemes is a

correspondence association which appears to be an analogue chat room.

Elsewhere we find the ‘polished little man’ who moves in truly

mysterious ways and may in fact be a group delusion; a séance that

turns into an illicit affair across dimensions; and a band of

travellers overawed by the occult power of their luxury luggage –

consumers possessed by their possessions. The surreal scenarios of

The Guesthouse at the Sign of the Teetering Globe remain vivid and

unsettling a century later. . This is the first book by Reventlow

to appear in English, in an edition that also features three short

stories by the author and an extensive afterword.

Countess Franziska zu Reventlow was born into the German nobility, and lived in the castle at Husum in Schleswig-Holstein, where none other than Theodor Storm, writer of the beloved but ghostly Schimmelreiter (Rider of the White Horse/Dykemaster, depending on which English translation you read) , used to tell her scary bedtime stories. A rebellious little miss, she broke with her family in early adulthood and went to live in Munich, the bohemian magnet of Germany at the turn of the 20th century. Fanny, as she was known, soon found herself mixing with the likes of Thomas Mann, Rainer Maria Rilke (who was an admirer of hers) and other luminaries of the German literary and artistic scene. She made a meagre living as a writer and translator. As the estrangement with her family was never healed, she needed to support herself and her illegitimate child. She never apologised for her son’s existence, given that she was a firm believer in and practicer of free love. In fact, she became the grande dame of bohemian Munich in the early 1900s. Reventlow’s lifestyle anticipated the freedoms of the Weimar Republic, which she didn’t live to see, as she was killed in a cycling accident in Switzerland four months before the end of the First World War.

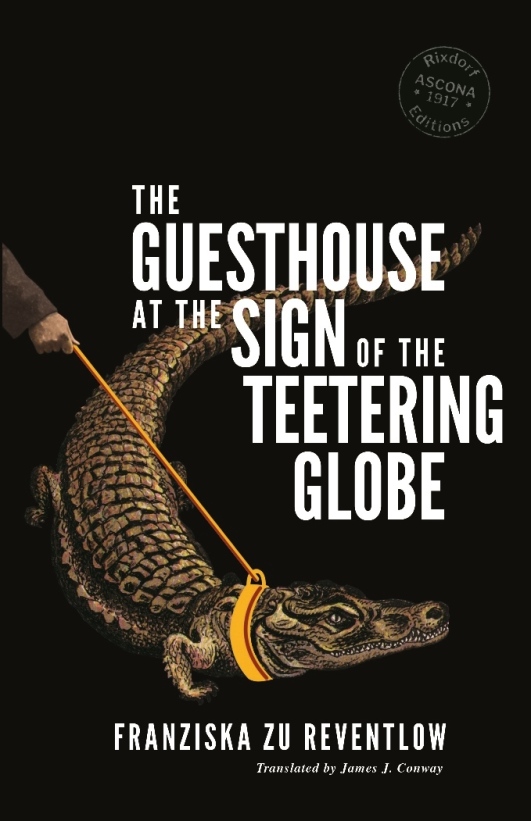

What is to be expected, then, in this collection of short stories, published in 1917? Stories typical of the various literary movements of the time: for example naturalism, decadence or expressionism? Or something as original as the woman herself?Perhaps the leashed crocodile featured on the front cover provides an answer. It makes an appearance in the title story, not as some fetish image or surreal metaphor, but as a fantastic occurrence that the reader is asked to believe is possible. There’s plenty of this, much of it rooted in the uncanny, as in the sense of that which simultaneously attracts and repels. In this Reventlow is reflecting the early 20th century fascination with spiritualism. Though, I will say, often with a light touch. Her stories contain sufficient rational grounding, if you will, to keep the reader wondering if she really is describing paranormal circumstances.

In The Little Polished Man a group of travellers are joined by the eponymous figure on multiple occasions. He is accepted until such time as the group realise that no one outwith their party is aware of his presence. At which point events take a strange disconcerting turn, and their unnamed visitor disappears. Is this simply coincidence? Is the little polished man simply a group delusion? Could he perhaps be a ghostly presence harking back to those bedtime stories with Theodor Storm?

My favourite story in this vein is that of The Belligerent Luggage. In it, an expensive set of luggage seems to resent being owned by a group of impecunious travellers, and conspires to ensure that, item by item, it is lost or stolen along the way. Lighthearted as this may be, anyone who has ever felt the weight of the material universe, when one thing after another (after another) goes awry, will enjoy this story.

The stories are mostly written in the first person plural by an anonymous narrator who is part of the travelling group, part of the ‘we’. This could be Reventlow herself, for as the extensive afterword, written by the translator James J Conway makes clear, these stories were inspired during Reventlow’s own extensive bohemian travels.

Many stories feature the classic outsider, an external who joins the group, only to upset the status quo. The little polished man is of this ilk. So too is Mr Otterman, whose unexpected presence at a swimming lake triggers a most unfortunate series of events. The title and opening story of the collection, however, contains a neat reversal of this trope.

We came across him – Hieronymus Edelmann that is – on a Spanish island, where he had been up to no good for years.

What a first sentence! Doesn’t it make you what to dive right in? Hieronymus Edelmann is waiting at the harbour to greet new arrivals, who he sends on to The Guesthouse at the Sign of the Teetering Globe. Upon their arrival, these travellers discover that Edelmann isn’t quite as noble as his name suggests, and that the guesthouse is nothing but a two-storey shack that is sinking into the ground. Still they stay and Edelmann’s purpose becomes clear. Instead of being the catalyst for division and strife, Hieronymus Edelmann wants to bind the group together into a mysterious association, the Flame Federation, and by means of a strange influence (more suggestions of otherworldliness) they all acquiesce. The spell unravels somewhat when he goes to buy himself a crocodile (as you do), at which point the travellers decide it is time to leave. Easier said than done – that’s when the fun really begins …

In addition to the seven stories that made up the original Guesthouse collection, the Rixdorf edition contains three others. The Elegant Thief is another in the ‘we’ travellers mould. It tells of a matchmaking attempt gone wrong, The change of register in the final two stories is quite extraordinary. Ill is a first person narrative; its contents the thoughts of a terminally ill woman. So authentic is this, that I don’t think I’ve read anything as simultaneously discomforting and moving. The premise of the final story, Dead, is that the consciousness lives on, following the body’s demise. The young man in question is aware of what is happening around his corpse. Worse still, he can hear what others think of him … and it’s time for a few home truths!

I thought this a strong collection with clear thematic ties and structures holding the stories together. To be honest, I could have done with less occult flavouring. Nevertheless I thoroughly enjoyed plots, characters, wry humour and some excellent storytelling. If Rixdorf Editions choose to bring more Reventlow to the Anglophone market in the future, I’ll be happy to read it. - Lizzy Siddal http://shinynewbooks.co.uk/the-guesthouse-at-the-sign-of-the-teetering-globe-by-franziska-zu-reventlow/

Though largely a conservative society, Wilhelmine Germany was nonetheless home to some of the most progressive and pioneering thinkers of its time. The pronounced militarism and censorship embodied by Kaiser Wilhelm II were counteracted by early human-rights activism and experimental, anti-reactionary art. Yet fiction and non-fiction from this period, in particular from exponents representing the liberal side of these conflicting forces, have remained largely unknown to Anglophone readers. Seeking to rectify this problem, the Berlin-based publisher Rixdorf Editions, in two authoritative translations by James Conway, has now released two texts never before available in English: The Guesthouse at the Sign of the Teetering Globe (1917) by Franziska (Fanny) zu Reventlow, a short story collection; and Berlin’s Third Sex (1904) by Magnus Hirschfeld, which according to Conway is “arguably the first truly serious, sympathetic study of the gay and lesbian experience ever written.”

It is hard to imagine a more scandalous and subversive figure in the German Empire than Reventlow, whose individuality and contempt for patriarchal norms (and even those of her feminist contemporaries) earned her the nickname “the bohemian countess.” Born in 1871 to aristocratic parents in Husum (in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein), she received the emotionally reserved upbringing typical of her class in the nineteenth century. Her family’s relocation to the more culturally vibrant city of Lübeck in 1889 offered her a window beyond this confining environment. Here, she had the chance to become acquainted with international literature, such as Tolstoy, Zola, and Ibsen, that challenged the hypocrisies of German social convention, above all the submissive role of women and the centrality of marriage. More passionate about art than literature, Reventlow sought freedom in Schwabing, Munich’s Montmartre and the cultural capital of early twentieth-century Germany. A satirist, free-love advocate, and (less than faithful) translator of French literature, she lived a life marked by debt and illness, unable to obtain financial stability through writing or marriage. Reventlow died in 1918 from injuries sustained in a bicycle accident, too soon for the emergence of Weimar Germany, where, with its more sexually-liberal norms and widespread experimentation in the arts, she likely would have thrived.

Guesthouse at the Sign of the Teetering Globe was published towards the end of World War I, with Germany engulfed in political turmoil and faced with the specter of defeat. Although most of the stories take place abroad, with characters in transit (e.g. on a train, a cruise ship) or on vacation, they nonetheless illustrate this period’s horrific violence, instability (for which the “teetering globe” featured in the title story is an apt metaphor), and tendency toward the grotesque.

Reventlow excels in capturing these era-defining characteristics. Her stories convincingly reflect the tragedy and absurdity of human events, seeming to echo the work of the nineteenth-century German writer Heinrich von Kleist, who stated that “the world is a strange set-up.” Here, in the words of David Luke and Nigel Reeves used to describe Kleist’s writing, Reventlow depicts “human nature” and the world as a “riddle,” where “everything that has seemed straightforward” becomes “ambiguous and baffling.” The influence of the darker side of German Romanticism can also be felt in Reventlow’s use of the uncanny (das Unheimliche in German, meaning literally “unhomely”), an encounter with a strange person, creature, or object that disturbs. It is employed to some degree in the Freudian sense, where the unsettling also attracts. Amplifying the impact of the uncanny is Reventlow’s frequent use of a third-person plural (“we”) narrative voice, a composition of characters that changes from story to story. Conway, in his afterward, notes that “this has an unnerving effect, as it seems to assume a prior knowledge of this ‘we’ (the characters) that we (the readers) cannot possibly possess. We are immediately on the back foot.” All these elements are acutely evident in the title story. A group of vacationers find their plans derailed upon their arrival at a Spanish island, where they are greeted by the eccentric Hieronymous Edelmann. Monocled and sporting a “monstrous” fan-shaped beard, Edelmann tricks the travelers into staying at the eponymous inn, a sinking, “dubious abode” inhabited by idlers “given to alcoholic overindulgence.” Once the vacationers suspect Edelmann of wrong-doing, they attempt to find accommodation elsewhere, only to have their efforts thwarted by (presumably) Edelmann’s menacing reputation. They find upon their return to the inn that Edelmann has enrolled them in the Flame Federation, an international pen-pal network he had recently joined, “which would afford tremendous pleasure to all involved.”

Edelmann (whom the painting The Garden of Earthly Delights by his possible namesake, Hieronymous Bosch, may have inspired Reventlow to endow with an affinity for exotic animals and hedonism) strikes the narrator as a charlatan with a “way of ignoring facts and realities,” from whom normally positive words (fundamental to Romanticism) such as “freedom,” “beauty,” and “pleasure” take on a hidden, sinister meaning. Though he has “given thought to his contribution to the refinement of mankind and its way of life,” his actions (e.g. his enrolling the guests in the Flame Federation without their consent, his attempt to prevent their escape from the island) betray a controlling and megalomaniac personality. Reventlow would die before the rise of fascism and large-scale personality cults throughout Europe, yet as her portrayal of the duplicitous Edelmann—as well as her propensity to base her characters on individuals she knew personally—suggests, perhaps she saw the characteristics of future tyrants in the public figures of her own time. When the narrator refers to the group as “we, the victims of Hieronymous,” her words may not be intended as melodramatic. Rather, perhaps Reventlow is alluding to the prospect of a catastrophic outcome for her country under the influence of such personalities.

“The Polished Little Man,” another of the collection’s stories, could be seen as a variation on this theme, a study of the collective madness and slavish dependency that surrounds such personalities. The story is centered around the tedious existence of five hotel residents in an unnamed “Oriental” town and their obsessive relationship with the “polished little man,” a well-dressed figure with an eerie laugh. The third-person plural narrator states that the “polished little man” is “constantly hopping in and out of our midst” recounting “anecdotes of exotic royalty and persons of high standing in his customary hushed tones.” Although the narrator professes that they can’t stand him, they become increasingly dependent on his presence (“he was absolutely unbearable. Perhaps this was precisely what attracted us”), so much so that their collective will is completely subject to his existence. He has become the master of their fate (“gradually, through no will of our own, he had become the focal point of all our thoughts, determining our lives entirely”) and the only causal agent for the occurrence of events (“or perhaps we had a vague feeling that if anything were to happen at all, that it would only happen through the polished little man”).

This relationship with the uncanny becomes more ominous as the story develops, and a reason for their trance-like state never emerges from these “the ambiguous and baffling” circumstances. One morning, a member of the group, the cavalry captain, returns with minor injuries from a search for a mysterious stranger, a “man with an iron bar” who has injured another member of their circle, and who is suspected of having a connection with the “polished little man.” In the narrator’s eyes, the captain’s injuries “seemed to be an even more sinister outcome than if he had died. Impudent fate was merely toying with us, it never took us seriously.” The arbitrary nature of fate takes on even more mysterious dimension when it is revealed that the “polished little man” seems to go unacknowledged by anyone outside the narrator’s circle, raising the possibility that he is a group hallucination. If true, Reventlow leaves no clues as to the the cause of these bizarre circumstances.

The theme of arbitrary destinies is further explored in “Mister Otterman,” where a scene of happiness is revealed as a mere aberration. At a seaside resort, the beloved of the lawyer Berger inexplicably dies as an unknown stranger introduces himself to her in the water. Suspecting the stranger (who goes by the name Otterman) in his beloved’s death, Berger challenges him to a duel. Berger manages to kill Otterman, but finds no respite in this outcome, as he becomes irrevocably haunted by the latter’s death.

Yet the most disquieting aspect of this story is how both men seem unable to stop this tragedy as it unfolds. Berger, on the one hand, “hardly knew what to feel … had no comprehension of himself, nor of the other man.” Otterman, on the other hand, in a way that seems to anticipate Meursault’s behavior in The Stranger, surrenders himself “blindly and submissively to his fate, a fate he hadn’t made the slightest attempt to avoid since the events of the previous day.” Berger concludes that “why he should have acted this way … would remain forever a mystery.”

Other stories explore different incarnations of the uncanny. In “Spiritualism,” a tale involving a séance with a husband whose murder has gone unsolved, the ordinarily mundane telephone becomes a communication medium for the dead. The spiteful possessions of “The Belligerent Luggage” take on a life of their own, abandoning their owners as they go on a cruise. In “The Silver Bug,” the discovery of a new species of bed bug leads to a romance between strangers.

Though the stories are uneven in quality (one can understand why the underdeveloped “The Elegant Thief” was omitted from the original German edition), Guesthouse at the Sign of the Teetering Globe, with its unconventional plot twists, carnivalesque characters, and existential concerns, will likely appeal to fans of both canonical writers like Kafka and Camus, as well as contemporary authors João Gilberto Noll and Can Xue. - Tyler Langendorfer

http://www.musicandliterature.org/reviews/2018/2/3/franziska-zu-reventlows-the-guesthouse-at-the-sign-of-the-teetering-globe-and-magnus-hirschfelds-berlins-third-sex

Born to the north German aristocracy, FRANZISKA ZU REVENTLOW (1871-1918) grew into a rebellious adolescent and abandoned her family once she achieved her majority. She spent the rest of her life in pursuit of total liberty – artistic, social and sexual – and became one of the most magnetic figures of Munich around 1900, when it was a dynamic centre of arts and letters and avant-garde notions. In the city’s bohemian circles she was both avid participant and astute commentator. Revered by her admirers as a ‘heathen Madonna’, Reventlow raised her illegitimate child alone, supporting herself with translation, satirical articles and even prostitution. She moved to Switzerland in 1910 but was unable to escape recurring patterns of illness and poverty, and died following a bicycle accident at the age of just 47. The five books Reventlow issued in her lifetime were all autobiographical to varying degrees, while posthumously published letters and diaries bear further witness to a life lived with bravery, integrity and passion.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.