Jay Bernard, The Red and Yellow Nothing, Ink Sweat & Tears Press, 2016.

‘The Red and Yellow Nothing has the feel of a heartfelt and intense investigation into something complex and significant, a true poetic quest, and one that has compromised little, if anything at all. It’s confusing, it’s challenging, it’s deeply satisfying, and it would be a real mistake to let such an exciting piece of work pass by uncelebrated.’

‘The pace and menace of The Red and Yellow Nothing has the horse pace of the ride of the Valkyries. It is time traveling through gender race and genre and is explored through an Arthurian legend – It reads like a song in my head.’ - Kathryn Williams, singer-songwriter, Ted Hughes Award judge 2017

‘The source text was translated into English by Jessie Weston in 1901. She commented, “the poem is a curious mix of conflicting traditions”. Bernard has more than lived up to the gloss. The pamphlet is a strange, lurid, baroque mash of tradition that calls to mind the “livingness” attempted by Hölderlin in his work with Sophocles’ Antigone. It does not stick with one style for long but is always dangerously alive…

…It is joyfully anachronistic (at one point Morien plays “the first computer game”). The world of the sequence is other, but complete. And the reader swallows each psychedelic trip. It is a magic trick to write back like this, into “the land before the story-o”, and for it to feel so crisp and alive and crackling.’ - Edwina Attlee The Poetry Review

Disclosure: Saw the poet read many years ago, don’t know Bernard personally. The book deals with social aggressions over race and gender, and a character in constant negotiation with their identity, or the identity imposed on their body. These are things I’ve tried to educate myself about, but have very much not experienced. It’s also a riff on a medieval text, which is not my specialism. Huge thanks due to Muireann Crowley for editorial advice.

The Red and Yellow Nothing was published over a year ago, and usually I’d take the loss and pay closer attention to pamphlet releases in future, but in part because of its Ted Hughes Prize shortlisting, and in part because I’ve never read anything like it, I want to spend a short time discussing it now.

‘The question of how a Moor, described as being black from head to toe, came to be the child of a knight of the round table is more about textual history than genealogy […] Morien is not racialised (except through contact with anyone reading this in the last five hundred years)’

I’ve talked on here about how truly radical texts need an uncommon amount of critical scaffolding to transport the (culturally centred) reader from canon-friendly reading practices to a place where those practices may be effectively criticised. Alongside this introduction Bernard has written two blog posts, at Speaking Volumes and The Poetry School, and they both helped me triangulate things in a book that does very little hand-holding. As Bernard argues, this quest is as much a textual as a physical one, and that requires a lot of lateral thinking, creative reading.The first lines are not words but punctuation:

‘.

:

;

,

,

.’

Morien ‘enters page left on his horse, Young’Un’, and ‘a bard of indeterminate gender’ sings::

;

,

,

.’

‘A silver wind came passing in

the distant land where books begin

where maids are men and hermits siiiiing

in the land before the story-o’

The poem’s action literally happens in a book, or a dramatized literary space, where postmodern ideas of text, contemporary slang and understanding of gender fluidity meet folk song and knightly romance. Wherever or whatever this ‘land’ is, it is a contested and uncertain place, and primes the reader to start making themselves uncomfortable. Perhaps it’s useful to visualise the story playing out onstage: The Red and Yellow Nothing regularly calls attention to its own artificiality and breaks the fourth wall, highlighting its episodic structure and the self-conscious humour of its narrative/stage directions. There’s that elongated ‘siiiiing’ that nudges the reader to imagine its vocalisation, the physical body behind the words. Maybe, again, this is a primer to think of Morien (and his dramatic monologue) as embodied also, both textual artefact and physical form; certainly the text and its players alike read his body like an open book. The narrator argues that ‘maybe we can empathise with the frustration one feels when the local people take one look at you, then hurry away from you before you’ve finished your sentence’. The ‘maybe’ seems pointed: as a middle class white reader I certainly cannot – the only thing that ‘maybe’ hinges on is who’s reading it. Morien, in turn, instrumentalises this fear:the distant land where books begin

where maids are men and hermits siiiiing

in the land before the story-o’

‘Tell me where my dad is, or I’ll kill you. Wanna fight?

I’ll fight you. I’ll take this sword and run you through,

I’ll have a disco inside you.’

Before either poem or reader meet Morien, or see anything of his inner life, we meet his violent response to the world. Whether this is due to a preternaturally hot temper, a perfectly understandable response to prejudice, or a mix of both is finally unknowable. He is, for now, all exterior.I’ll fight you. I’ll take this sword and run you through,

I’ll have a disco inside you.’

The following episode is taken up by two perhaps competing exteriors, both unreal in their own ways. The section begins with William Dunbar’s hateful poem ‘Of A Black Moor’, describing a white woman in extreme dishygiene and blackface posing as a black woman for the crowd’s entertainment; Morien spots a woman in the crowd, wearing red and yellow, ‘both cheeks shining black like whorls of wood’, ‘shoulders like a proto-stradivarius / lost to the sea’. She disappears and Morien wakes drunk in a field, ‘the dew that / cradles him finds the word: innocence’, a beautifully poised moment that allows Morien his youth and inexperience, and allows the reader empathy for a character who in this moment is completely lost. It’s possible the idealised and vanishing woman appeared in Morien’s imagination in self-defence against the collective ridicule of blackness, but the gloves left in Morien’s hands seem to suggest otherwise, and the section ends:

‘a red and yellow nothing stands with

her back towards him; red lace

yellow silk, and no-one there.’

The Red and Yellow Nothing is full of these doublings and halvings: Morien and his father dream corresponding parts of the same dream, there is a town split down the middle with one half in summer, one in winter, one character sings a song about promising a song, other examples abound. While a recognisable literary trope, and one that feels right in a medieval romance, its sheer abundance adds to the uncanny sense that the usual relationship between story and protagonist (or even reader and story) has broken down, is in transition to something stranger.her back towards him; red lace

yellow silk, and no-one there.’

The book doesn’t shy away from the ghoulish. Later, a female convict is ‘hog-tied’, ‘hanging from a pole […] writhing like an errant C’. Though that last simile seems to point to the girl’s existence as a leftover trope of misogynist writing, her fate is still extremely gruesome. A figure called ‘The Something’, which might be the ‘red and yellow nothing’s grim counterpart, emerges from the trees and draws the woman bodily into its anus before releasing her for burial. Bernard’s account is visceral and revolting, giving the whole scene the air of an awful ritual or sacrifice. Like Morien, the woman is painted in innocent tones, ‘She is a child’s finger’, ‘crying for god and her mother’, and their connection seems substantialised by a later, crucial episode in which Morien is transformed and processed (‘Morien is currently a turd.’) by sinking to the lowest point in Earth’s sea and being ‘expelled’ ‘from the slippy slide / of time’. Where the woman’s ordeal is socially inscribed and compulsory, Morien’s seems to be the result of some psychological shift that originates in dreams and comes to reorder reality as Morien perceives it.

If it wasn’t clear, The Red and Yellow Nothing is, by any standard in common currency, extremely weird. But there’s something so clear and graspable and purposeful about that weirdness that has kept hold of my imagination weeks after first reading it. Shortly after the horrific scene discussed above, the whole adventure becomes increasingly surreal, increasingly subject to bizarre and arbitrary laws and rules. And yet those rules are almost followable, the story’s progression right on the brink of logical, while the meanings attached to Morien’s body become increasingly nonsensical, or perhaps their inherent nonsense is revealed.

I can’t help feeling that in someone else’s hands the book and its narrative would have felt pretentious, or merely arbitrary, rather than a faithful account of the odd trajectory needed to get from the book’s start to its finish. Throughout, there’s a wry humour (‘in which Darkness herself comes across Morien’s dreaming body and is like woah’) that keeps the story grounded, human, and for all its depictions of suffering and brutality, Morien himself (or themself, for a significant passage) is neither the butt of the joke nor a punching bag. The book clearly cares for him, however much it focuses on the change and uncertainty being visited upon him.

Most of all, I think, this is a story about blackness and how the world responds to it. The white people at the fair and the people in the book’s first episode won’t talk to Morien, and the brutal execution scene is implicitly enacted by white society. Darkness appears as a character, and while she doesn’t interact with Morien either, she is invested in his story and knows he is both closer to and further from Camelot than he thinks. Five African soldiers in Scotland speak the book’s most peaceful and mindful sequence, on ‘the strangeness of the land they’re in’, articulating a complex thought about empathy and mutual respect:

‘Their footsteps of mine.

I want to know what people

to whom I give everything

feel when they think they are me.’

The book’s climactic scene has Morien encounter the figure of Saint Maurice, a character who the writer of the Medieval POC tumblr – which Bernard cites as an originary source for the book – argues might be cognate with Morien himself, given the shared linguistic root of their names and the habitual shuffling of characters’ identities in romances of the period. Given this final muddling, the final passage seems deeply significant:I want to know what people

to whom I give everything

feel when they think they are me.’

‘The statue stirs, like it’s about

to speak, then of its own accord, blows away.’

This may be the story’s final doubling, or the final doubling’s reconciliation. The canonised Christian martyr Maurice gives way, of his own volition, to the transformed, multi-identitied, genderqueer Morien, to whom Christianity and its official sanctioning have meant nothing. The next moment, Morien finds Camelot, and Moraien begins.to speak, then of its own accord, blows away.’

It’s incredible that so much has been fit into about 24 pages, including the handful of full-page illustrations by the poet, without feeling overburdened. The Red and Yellow Nothing has the feel of a heartfelt and intense investigation into something complex and significant, a true poetic quest, and one that has compromised little, if anything at all. It’s confusing, it’s challenging, it’s deeply satisfying, and it would be a real mistake to let such an exciting piece of work pass by uncelebrated.

- Dave Coates Dave Poems

‘For who can bear to feel himself forgotten?’ (W.H. Auden ‘The Night Mail’). Many poems have fallen underfoot in the forests of memory. Jay Bernard’s pamphlet makes brilliant use of one of these. Morien is a Middle Dutch romance; its hero, a Moorish knight. Bernard inroduces her poem as ‘an inquiry into the idea of blackness in Europe’ before slavery.

This retelling of Morien is wildly appealing. Its opening (which can be sung) owes less to Le Morte d’Arthur than to topsy-turvy Disney, spiced with folk song in the style of the late great Kenneth Williams…’ - Alison Brackenbury Under the Radar

It is difficult to put a finger on the immediate aftermath of reading The Red and Yellow Nothing: there is puzzlement, rage, and wonder, but ultimately the sense that Jay Bernard has created a rare and beautiful thing. Part contemporary verse drama, part mythic retelling, the pamphlet – containing one long poem, broken into sections with stage directions – is framed as a ‘prequel to the tale of Sir Morien, son of Agloval’, narrating the backstory of the young Moor’s arrival in Camelot.

Its premise is cleverly, and comically, formulaic. Morien and his horse, Young’un, gallop onto the scene in search of his father, a knight of the Round Table. They kill a poet, lose a tournament, encounter a mysterious woman, find Morien’s mother in a strange village, and endure other fantastical trials before crossing a wasteland to Camelot. The true quest, however, is not Morien’s but ours. Employing metrical ballads and concrete poems with equal vigour, Bernard takes us on a visual and allusive journey to test the imagination, thus putting the poet’s resources of sight and sound to full use.

While two conscientious footnotes point us to direct quotes from William Dunbar and Kendrick Lamar, it does not take long to see that the entire text is crinkled with allusions. Bernard’s use of Sir Morien’s story alone is a case in point: the tale has tangled roots with various Arthurian tales, including Parzival, and she draws fully on the immigrant resonances of Morien’s name (which in Medieval Welsh means ‘sea-born’) as well as his ethnicity. The fact that ‘Morien’ also derives from the Old Welsh ‘Morgen’, which is the spelling Geoffrey of Monmouth uses for Arthur’s gentle healer (or ambitious nemesis) Morgan le Fay, further lends her project its deliberately ambiguous – and subversive – character.

But this is not merely another Arthurian remix. Bernard casts a wry eye over the past, playing with our modern expectations; from start to finish we recognize supporting actors that look and sound, uncannily, just like we expect them to. Morien and Young’un enter (‘page left’) introduced by a bard – rhyming of ‘the distant land where books begin / where maids and men and hermits siiiiiing’ – whose over-the-top, modern lyrics fall into the quatrains of a minstrel’s song. Before they exit, they encounter St Maurice, the third-century black martyr and leader of the Theban Legion, and he is dressed (of course) ‘like a burned manuscript: gold halo, gold / on the collar of his breastplate’. The half-seen, half-remembered quality of each description brings the narrative’s intertextuality to life, and in one of Bernard’s own lines, ‘it is hard to hold the two halves of the past and future apart.’

Poems that aim to do this much with the past often buckle under their own weight. It takes a poet of Bernard’s skill and sensitivity to keep the lyrical movement of the sequence alive, and the joy of this pamphlet is in its language. From Morien’s exuberant taunting (‘Wanna fight? / I’ll fight you…I’ll have a disco inside you.’) to the echoey dream-world he shares with his father in a haunting twin cinema (‘black was the light / black was the field / and the rain was / falling backwards’), reading The Red and Yellow Nothing brings continuous surprise. Bernard is careful not to let her inventions slip into wordplay for its own sake. Many excerpts deliver hard-hitting critiques of colour and femininity; in one scene, after a wild man has won ‘a kiss from a black lady’ in a tournament, and the assembled scrum of courtiers express their relief that ‘beneath her skin the black was white in fact’, Bernard writes –

How white, is another thing. If the colour

Was the smell, then the maid was grey. Tallow,

Fish-oil and potash; saddle seat; monthly blood

In dusty streaks along the base and up the crease.

Brilliantly, this is what never happened as it happened, and not as we expect.

Ultimately, Bernard succeeds in bringing the travelling pair to life, and fleshing out her mysterious knight in the fullest sense. As they arrive at part x of the poem, Morien (now without Young’un’s reassuring presence) undergoes ‘something we won’t call a transition, exactly’, and we get a precious glimpse of the possibilities that are larger than both life and legend. In the slow, almost prenatal dusk where ‘shadow and form change place’, a new Morien is born: ‘s/he has ceased to be a thing, / but a rule – a how or why, / a reason, / a what things are / governed by’. Morien’s plea – and perhaps Bernard’s – is to put aside all we think we know about past and present, about the thingness of things, and learn the value, freedom, and colour of nothing itself. There’s something to be said about that.

- Theophilus Kwek The London Magazine

The Red and Yellow Nothing is the story of a quest… or is it, and if so, for what? Jay Bernard has unearthed an Arthurian tale from a Middle Dutch poem of possible French origin, translated into English a century ago. Sir Agloval, a knight travelling in Moorish lands, meets a princess and then leaves her. She gives birth to Morien, who grows up and rides to Camelot in search of his father. He has some adventures, and there’s a happy ending… in the original.

In The Red and Yellow Nothing things go differently. I’ll talk about it in terms of the story, which is one way to give an idea of the variety in this unusual pamphlet. Adventures become experiments in time, space and identity, spinning out of a kaleidoscope of poem-episodes, leaving me dizzy and disoriented.

At first we seem to be following a conventional quest, updated with brio and irony. Morien “enters page left on his horse, Young ’Un”, to be serenaded in assured ballad-style by a bard:

Some things we know but can’t say why

the dark is what light travels by

a blind man’s finger is his eyyyyyyye

in the land before the story-o

Next, Morien makes a hell of a fuss because no-one will help him. I sense that he’s expressing the hurt of any abandoned son, plus the hurt and frustration of a stranger, “black from head to toe”, who people just want to get away from (poem II):

Everyone says

I know not good knight where your father dwells,

mincy mincy moo. Ergot brained fuckers. Fight me.

Everyday racism is just the start; in poem III, Morien happens upon a competition in a castle. He doesn’t win, and the prize is a kiss from a blacked-up woman (losers’ prize: kiss her arse, which is smelly, details provided) while the early sixteenth century Scottish poet William Dunbar recites his poem ‘Of Ane Blak-Moir’, a cruel and, to modern sensibilities, repellent love-parody. Then Morien spies a black woman in the crowd, who turns to leave:

Her shoulders like a proto-stradivarius

lost to the sea. Which sea, Morien couldn’t say.

A red and yellow one, a sudden one, sudden.

.. and vanishes. Hence the pamphlet’s title. This episode, part Monty Python, part medieval /16th century horror, part brief love lyric, raises questions about what’s real and what’s not, who anyone actually is, and the experience of blackness in a world that was racist before the concept existed.

Morien witnesses a horrific, nightmarish execution scene, and poem VI contains a strange dream:

I dreamt that I dreamt that I woke in the wilderness

wanted for something and walked in the wilderness

black was the light saw folks made of green

and the rain was falling backwards

Bernard’s formal versatility makes poems like this stand out. Not that they aren’t all worked on, with vividly fantastical descriptions and striking turns of phrase. Her skill won’t surprise anyone who read her first pamphlet, your sign is cuckoo, girl.

There are illustrations too, by the author, which perhaps work best with the more abstract parts of the narrative; for me they don’t enhance it, unlike Bernard’s useful notes and introductions to most of the poems.

The theme of blackness and light runs through everything and attracts interesting language, as in poem VIII, where African soldiers playing a firelit game talk about the strangeness of Scotland, “how different the flame is to air”, or poem VII, in which Darkness herself takes an interest in Morien:

Morien’s body speaks to

the thin high black he

sleeps in.

Later Morien finds a two-pound coin, crashes through time, becomes s/he and undergoes other transformations in a prose poem (XI) that’s part Hieronymus Bosch, part Salvador Dali, part modern gaming/dreaming fantasy. I had trouble linking this to the story, though it contains some inventive stuff:

Hadopelagic:

A roseate spoonbill snorts crushed ecstasy off the belly of a blow-up doll. Eats bunga kuda.

Sort of recovered but very confused, Morien continues his (his?) quest through “Earth pocked like natrolith and riven / with dried rivers” (XIII). He appears to succeed – he sights two knights, and the book ends with a quote from its source poem, in which Morien arrives at Camelot.

He was all black, even as I tell you:

his head, body and hand

was all black, save his teeth;

and weapon and shield, armour,

were even those of a moor,

and as black as a raven.

That coda returns us to the beginning: the familiarity of an Arthurian tale in which a stranger appears, and we know there will be adventure. But after all he’s experienced, who is Morien? What was his strange journey all about, and why should anything happen the way we think it might?

There’s some background on the pamphlet, and depictions of black medieval knights, here; the link is in Bernard’s credits. The Red and Yellow Nothing was joint winner of the 2014 Café Writers Pamphlet Commission, and is published by Ink Sweat & Tears. - Fiona Moore, Sabotage Reviews

Winner of the sixth Cafe Writers Commission judged by Kate Birch, Chris Gribble and Helen Ivory, The Red and Yellow Nothing explores Sir Morien’s search for his father, Sir Agloval, a knight of King Arthur’s Round Table. It’s loosely a prequel to Morien: A Metrical Romance Rendered into English from the Middle Dutch, translated by Jessie Laidlay Weston (1901). Morien travels from Moorish lands to England to start his quest to find his father, in a sequence split into 13 parts, each starting with a stage direction. In II, the introduction suggests maybe we can empathise with the frustration one feels when the local people take one look at you, then hurry away from you before you’ve finished your sentence. Here, Morien asks a bard:

I'll fight you. Why don't you come out and face me and

fight me and tell me what you know? I've been riding since

I don't know when, now I don't know where,

why don't you come and face me. Everyone says

'I know not good knight where your father dwells.'

Naturally someone who’s trained as a knight since childhood would instinctively and as a reflex turn to his sword. The bard sings a story of a knight setting out on a quest but cannot answer Morien’s questions directly, giving rise to frustration. Readers don’t know who the everyone referred to is. Are they unarmed commoners wary of a knight’s sword? Are they being truthful about not knowing where Sir Agloval is? Do they refuse to answer because they are naturally suspicious of a stranger or because of some other prejudice? In not spelling out that Morien is black, Jay Bernard allows the readers to explore ideas around racial prejudice without directly being told this is the issue.

In III, Morien joins a competition where the prize is a kiss from a black lady; but he loses to a wild man who turns out to be a king. And as he kisses the black woman, the other men form a line, they pressed their mouths against the woman’s ass, laughing. The woman is revealed to be white.

How white is another thing. If the colour

was smell, then the maid was grey. Tallow

fish-oil and potash; saddle-seat; monthly blood

in dusty streaks along the base and up the crease.

As Morien pressed his nose into the fine clothes

and finer stench, he caught a woman in the corner

of his eye: she was dressed in red and yellow, sat

silent in the crowd, mouth and lips full and pursed,

both cheeks shining black like whorls of wood.

The richness of detail, particularly of smell, is apt. By showing, the poet doesn’t need to remind readers these are historical times. Morien loses the woman wearing red and yellow in the crowd and realises she was a figment of his imagination, an ideal in contrast to this king and woman who sought to deceive. The king, by hiding his skill underneath the clothing of a commoner, is tricking his opponents into losing. The woman by appearing foreign, is using her apparent exoticness to entice competitors into thinking her a rarer prize. Small wonder then that Morien catches sight of something that appears ideal (but is in his imagination), a red and yellow nothing that reminds him he is being diverted from his quest.

Continuing his exhausting journey, Morien is struggling to keep a grip on reality. In XII, catching a rare night’s sleep in a hermitage:

His lids flutter, the hatched lashes betray a milky slit. On it:

the surface of a dream in which a hermitage roof slid down

a century ago and left a jagged aperture above. Below,

Morien appears skeletal and genderqueer:

promise that you

will

sing

about me.

Occasionally a modern colloquialism slips in to draw attention to a particular point. Morien’s nightmare reminds him of his quest: to find a father who left before he was born and the unvoiced fear of rejection. Rejection would undo Morien’s identity as the son of a knight.

The Red and Yellow Nothing is an exploration of identity, primarily through race, using its medieval setting to get away from modern labelling and to encourage readers to think about their own prejudices. The poems are rich in detail but remain mindful to need to progress a plot and tell the story. - Emma Lee, London Grip

Is ‘horrible’ horribly good?

I didn’t like this ‘prequel to the tale of Sir Morien’ but I can’t forget it, which must – I think – be sign of potency. What I remember best is the bit that appalled me most. That’s the way memory works: we have hotspots for disgust, sex, violence.

… I’m reminded that when I first met the word ‘allegory’ I thought it meant a story you couldn’t fully understand. And so it is, for me, with the The Red and Yellow Nothing. I don’t understand it at all but I can’t forget it. I wish I could. - Helena Nelson, Sphinx OPOI Reviews

Bernard turns the story of a little-known medieval knight into a fresh, witty and exciting quest for identity, in an imagined medieval world that is equal parts strange and familiar. The poem is interspersed with gorgeous, richly textured images. - Diva (UK)

Jay Bernard on The Red and Yellow Nothing

…The Red and Yellow Nothing was like that. I didn’t realise what I’d written until I’d written it.

There are many influences. My introduction to the story begins with a quotation from Jessie Weston about the story of Morien in its current form – part of an idiosyncratic C14th compendium called the Lancelotcompilatie: “As it stands, the poem is a curious mixture of conflicting traditions.”

When I first started this project, I tried to be coherent. I tried to make it a neat confection of historical figures interacting with each other. And it didn’t work because the technical requirements of such a story are not neat.

The story itself isn’t neat, how could my interpretation seek to neutralise, formalise, make coherent?

More, including the influences of Kendrick Lamar, The Child Ballads and, we kid you not, Super Mario can be found by clicking the link below.

Blog, March 2017 Poetry School feature where each of the 2016 Ted Hughes shortlist is asked to blog about the writing process.

…I wanted to write something about blackness that wasn’t tragic, but still spoke to the situation we are currently in. The paradoxical nature of now: the way you can be erased, snuffed out, disfigured, distorted, while being privy to the remarkable insight that is only possible from the margins.

I thought that writing about black characters in a world before the construct of race as we currently know it would be a liberating move. I thought it might open up a contemplative space less weighted by the ballast of the media, and American media in particular. We are always expected to view ourselves in a certain way – and I wanted to present and view Morien completely differently.

Interview, October 2016 Poetry Spotlight

“I wanted to go back in history and begin exploring a time when blackness was not the thing it is today.”

Jay Bernard is one of 10 writers returning to the US for part two of Breaking Ground. This year, the group is visiting the West Coast for a series of readings, workshops and university visits. Jay won the 2004 London Respect Slam and is the recipient of a Foyles Young Poet award (2005). She is from London and has been published in in numerous international journals and magazines. Her first pamphlet Your Sign is Cuckoo, Girl was the Poetry Book Society’s pamphlet choice for summer that year. She was the inaugural 2012 writer-in-residence at the Arts House and National University of Singapore and 2013 City Read young writer in residence at London Metropolitan Archives. Her second book, English Breakfast, appeared in 2013, and her most recent book The Red and Yellow Nothing, has just been published by Ink, Sweat and Tears

Jay is also a programmer for BFI Flare: London LGBT Film Festival and, as a graphic artist, her work has appeared on the cover of Wasafiri and in Chroma, Diva and Litro. In her own words: ‘I am interested in graphic/public art, film, literature, technology, cyber-feminism, queerness and impending doom(s).’

We caught up with Jay Bernard just before her departure to the US.

Speaking Volumes: You were part of the Breaking Ground Tour in 2015. Were there any moments/events that particular stood out for you as highlights, and why?

Jay Bernard: I managed to get on the bus that was heading to Solomon Island and joined in the ceremony they held for the slaves there. Everyone walked out onto the jetty and dropped flowers, and there was a slow current, so as the sun was sinking, there was magenta, yellow and violet on the surface of the river. Beforehand, one of the women conducting the ceremony said that if you can’t remember a name from history, make one up – your imagination would almost certainly correspond with the destitution someone was experiencing as they stepped off the boat. So it was very poignant and I was holding it together, and afterwards they gave us little bottles of water that contained drying agent, which I found completely undrinkable.

SV: Your new collection The Red and Yellow Nothing has just been published by Ink Sweat and Tears, and it was joint winner of the Cafe Writers Pamphlet Commission. Can you tell us a little bit about the collection, and what led to you deciding to write about this particular subject?

JB: I came across the story a few years ago on medievalpoc.tumblr.com and decided it would be an interesting concept for a book. The original idea was to profile several black figures from European history, including Sir Morien, but as I was writing, I realised that I wanted to do something with more of a narrative drive. So I decided to write a prequel to the story of Sir Morien instead. The Red and Yellow Nothing is basically the figure of Morien in the twilit, pre-story universe before he enters the narrative that was eventually passed down. But I didn’t want it to be a strict historical project, so it’s very anachronistic, and there’s some gender bending in there, shape-shifting, Kendrick Lamar makes an appearance as does William Dunbar.

I wanted to write this pamphlet because I wanted to go backwards in history and begin exploring a time when blackness was not the thing it is today, when Moors culturally dominated the British, when race/racism had not yet been invented. There are some interesting scenes, such as when Morien rides to the beach and none of the sailors will take him because of his appearance. It’s very easy to read that as racism as we now understand it, but in the story its pitched as a kind of stupidity; the other figures, particularly Sir Agloval, who is Morien’s father, do not have an issue. So what is that? Also, Morien is described as literally black, yet his father is, presumably, a pale-skinned European. His mother is described as simply a Moorish princess. So this story has cultural / ethnic difference in it, but it’s being pitched in a way that you and I probably don’t understand and possibly contaminate. Or not, as the case may be.

SV: How much research did you do in order to write the collection, and how long did the entire project take?

JB: I wrote it over two years. It started out as portraits of different figures – some of whom are still in there, such as the black lady who is mocked by William Dunbar and Sir Maurice. Then I decided to make Morien the narrative thread, so I wrote out a prose version of the original tale, took some of the most interesting scenes and tried to thread it together that way. I was going to have different figures from history interrupt the tale at key moments, but that didn’t work out. I then wrote some really weird poems which later became the section about the five African soldiers whose bodies were found in Scotland, and finally I hit on the idea of making this a prequel. I think I was being too strict with myself in the beginning, whereas this is basically me doing the opposite of scholarship and the opposite of history. Sometimes I worry that someone is going to read it and haul me in front of an academic judge for not sticking to the details.

SV: In addition to writing, you’re also a graphic artist. Does your artistic practice influence your writing practice in any way?

JB: I’ve done quite a few projects that are part text, part graphic. Yemisi Blake and I collaborated on London-wide installation for TFL that was part poetry, part graphics. I like to draw comics. The Red and Yellow Nothing has images in it. I’ve done the covers for all my own books. So yeah, maybe the two things are entwined. - Interview, April 2016, Speaking Volumes

Jay Bernard, Other Ubiquities, 2017.

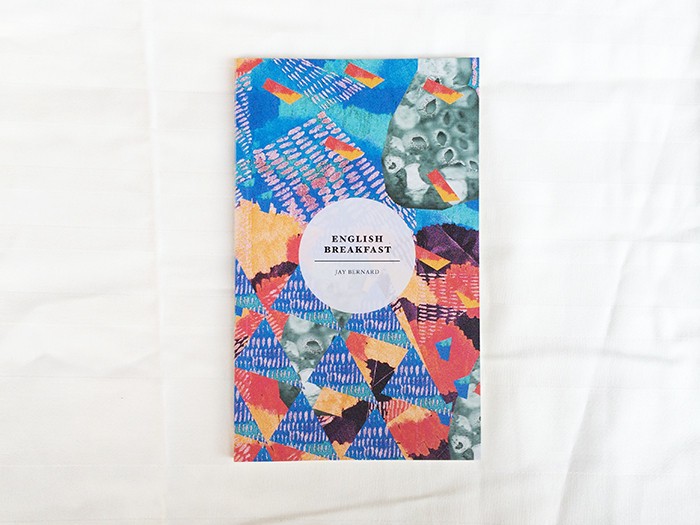

Jay Bernard, English Breakfast, 2013.

In 2011 I went to Singapore to undertake a fellowship at the National University. It was amazing - a lot came out of it, including this pamphlet,

From 'Coming from Ankhit':

Do you Jay? Do you rub lotion on an otherwise bald white skin

to make it blacker? Are you really a Jersey cow, or are you like

the long lashed sabu, gold, really, or are you really skinless

like the pig, being dead, being skinned with a knife?

From 'The Language of Fish':

In my flat there’s a photo of a boat a little way out to sea.

Now it’s reclaimed land and sepia prints are the only proof

that fishermen ever returned to the one-storey shop-houses

lining the sea front, and lit joss sticks in the sand. That temple

sent the smoke of gratitude into the fickle dark to find some

warm ocean current, tasted by whoever, whatever, was listening.

From 'A Milken Bud':

I was never a mother; I never brought to term

a lit cluster of dividing eggs, thriving like bulbs

and streaming behind me, like the proud amphibious

matriarchs hatching their young in my hip bone.

Jay Bernard is a poet, writer, and film programmer. Her published pamphlets are Your Sign is Cuckoo, Girl (tall-lighthouse 2008), English Breakfast (Math Paper Press 2013), and The Red and Yellow Nothing (Ink Sweat & Tears Press 2016).

Jay’s poems have also been collected in The Salt Book of Younger Poets (Salt 2011) and Ten: The New Wave (Bloodaxe 2014).

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.