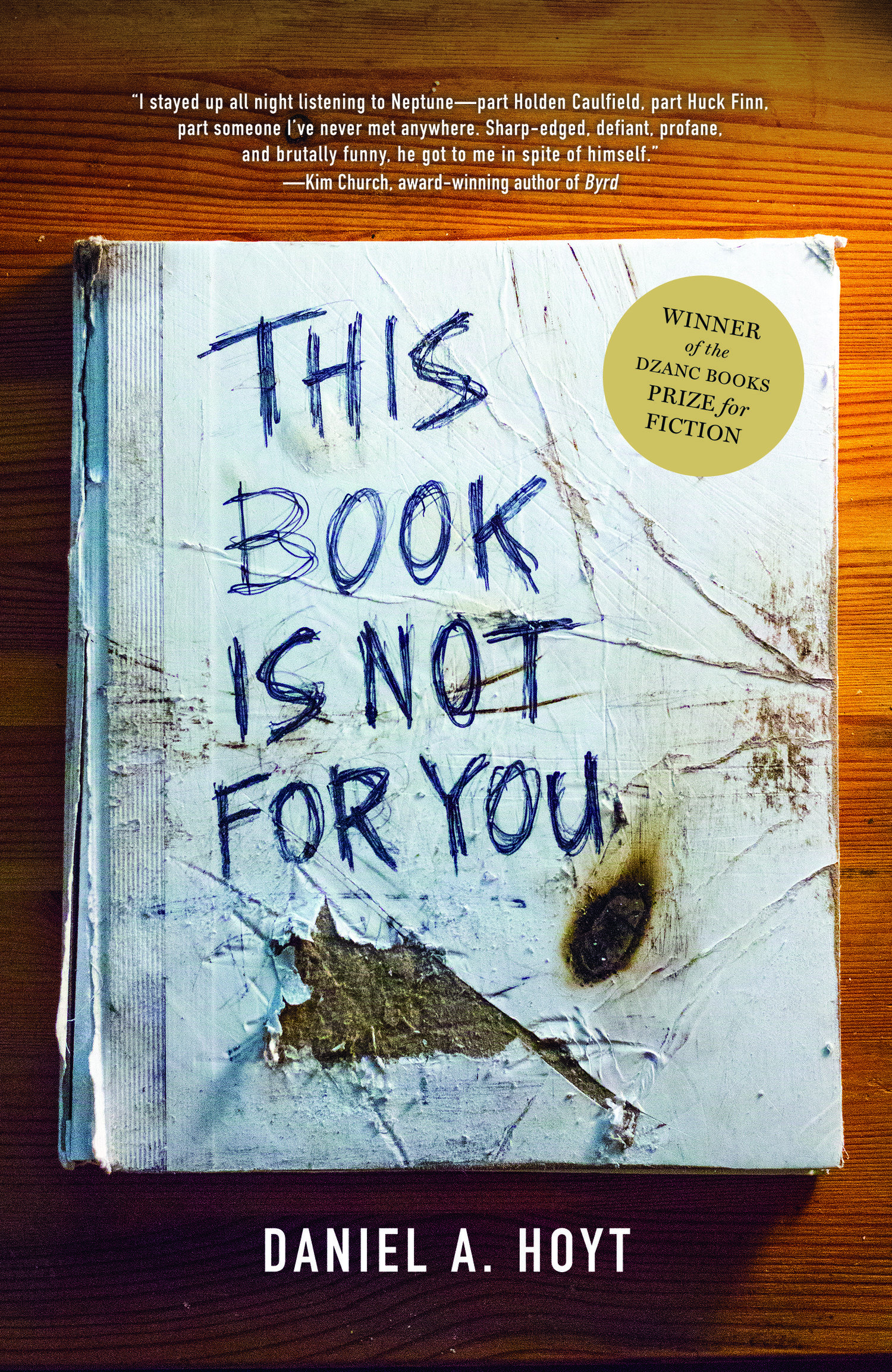

Daniel A. Hoyt, This Book Is Not for You, Dzanc Books, 2017.

Winner of the inaugural Dzanc Book Prize for Fiction

Utilizing an innovative mashup of genres, ranging from pulp fiction, dark comedy, and metafiction, This Book Is Not for You charts the actions of nineteen-year-old Neptune, a misfit and punk haunted by the death of his parents. Having fallen in with an anarchist group determined to blow up a university building, he steals the dynamite instead, igniting an entirely different brand of trouble: the murder of his mentor; a three-way manhunt; and the mystery of the Ghost Machine, a walkman that replays snippets from his own twisted past.

Told in a nonstop chain of Chapter Ones, Daniel Hoyt’s debut novel explores the clash between chaos and calm, the instinct for self-destruction and the longing for redemption. – from the Dzanc Books website

“I stayed up all night listening to Neptune—part Holden Caulfield, part Huck Finn, part someone I’ve never met anywhere. Sharp-edged, defiant, profane, and brutally funny, he got to me in spite of himself.”—Kim Church

“The energy of Hoyt's prose carried me until I was reading at a pace I never do, and panting at that. A page-turner experimental novel.”—Carmiel Banasky

“This is not a confession, but a caustic blend of pulp and metafiction that surrounds a haunted Walkman, a murder, wishful anarchists and a constant reset for the reader. Every chapter is chapter one, but Hoyt knows just how to pull the strings..”—Andrew Sullivan

"This Book Is Not For You introduces the world to Neptune—a self-destructive and overly self-aware hero for our times. Neptune’s misadventures are funny, harrowing, thrilling, and sweet, and the novel’s recurring Chapter Ones give a fresh start. Neptune’s bad decisions might make you cringe, but you’ll cheer for him... An exciting and inventive novel."—Craig Finn

The snarky, experimental first novel by Hoyt (author of the story collection Then We Saw the Flames) consists of one “Chapter One” after another narrated by an abrasive young man who calls himself Neptune. After leaving the University of Kansas, he falls in with a group of anarchists and, on a whim, takes off with their supply of dynamite to thwart their plan to blow up a building. On the run, he arrives at the apartment of his favorite professor, only to find that her head has been bashed in, and she now appears to him as a silent ghost, accompanying him wherever he goes. The narrator, quite conscious that he is a voice in a book, frequently addresses the reader directly and belligerently. “You hate me already, I can tell,” reads one chapter in its entirety; “You still there?” reads another. While the series of first chapters might suggest a time loop, in fact the novel moves along linearly, with a few flashbacks. Frequent references to The Catcher in the Rye and Huck Finn suggest that Hoyt is aiming for a contemporary version of those tales, with an extra helping of profanity and violence. Though Neptune’s story might not be for all readers, some may be carried away by the momentum of his sharp voice. - Publishers Weekly

The snarky, experimental first novel by Hoyt (author of the story collection Then We Saw the Flames) consists of one “Chapter One” after another narrated by an abrasive young man who calls himself Neptune. After leaving the University of Kansas, he falls in with a group of anarchists and, on a whim, takes off with their supply of dynamite to thwart their plan to blow up a building. On the run, he arrives at the apartment of his favorite professor, only to find that her head has been bashed in, and she now appears to him as a silent ghost, accompanying him wherever he goes. The narrator, quite conscious that he is a voice in a book, frequently addresses the reader directly and belligerently. “You hate me already, I can tell,” reads one chapter in its entirety; “You still there?” reads another. While the series of first chapters might suggest a time loop, in fact the novel moves along linearly, with a few flashbacks. Frequent references to The Catcher in the Rye and Huck Finn suggest that Hoyt is aiming for a contemporary version of those tales, with an extra helping of profanity and violence. Though Neptune’s story might not be for all readers, some may be carried away by the momentum of his sharp voice. - Publishers Weekly

Hoyt’s debut novel (following a collection of stories, Then We Saw the Flames, 2009) is an unconventional whodunit in which who did it is not the point.

Nineteen-year old Neptune is at the nexus of many different storylines. He's a thorn in the side of the local Black Block, an anarchist commune whose dynamite he has made off with; a late-night knight in shining armor for his mentally ill former professor, Marilynne, whose life he cannot save; a link to the past for the mysterious Saskia, whose dead brother’s shaman-hexed Ghost Machine (a Walkman circa the 1990s) has started spinning the tape of Neptune’s life and cannot be muted or turned off. Adrift, multiply abandoned, alcoholic, and emotionally scarred, Neptune has a tough, wry, and at times movingly vulnerable voice which guides us through the underbelly of anarchic/punk Lawrence, Kansas, as he runs from the anarchists, the police, his past—both recent and way-back-when—and, most of all, his future. Will Neptune evade the anarchists, intent on either recovering their dynamite or enacting their revenge? Will he successfully overcome the minefield of his own personality to work things out with Saskia—who is beautiful, brainy, patient, penitent, and has many other Manic Pixie Dream Girl traits beside—and, most important of all, will he find out who killed Marilynne? Will he tell us if he does? Told in an unending string of first chapters, Hoyt's book beguiles even as it actively befuddles. Ultimately, though Neptune’s hapless violence, his psychic damage, his deep attachment to equally damaged literary lost boys like Holden Caulfield and Huckleberry Finn are both engaging and sympathetic, his insistence on refusing to tell the reader pertinent parts of his past and his near constant defensive rejection of the reader’s attention are relied on too heavily for the surprisingly slender weight of the plot to withstand.

The events get lost in the telling. Though the book is full of piquant details, juicy language, and the totally believable chaos of characters living on the counterculture fringe, it is outpaced by the restless, relentless energy of its main character’s voice. - Kirkus Reviews

It’s time to stop talking about fiction categorically, time to shut the fuck up about metafiction, postmodernism, experimentalism. It’s time to remember Rabelais and Petronius, Burton, Arlt and that other guy (women? I suspect they are in the vanguard—I wish I could experience the genderrific thrill of having a lady named George enter the man’s world just to show them how easy it can be if you take your genitalia just a little less seriously). The history of fiction is a very long one, a history of free prose winnowed suddenly into a conformism commodified into an embarrassing self-regard—mirrors previously used to perform tricks became instruments of judgment. How it happened is not my concern, other than to say it took a great deal of cowardice, collaboration—in the shave their heads sort of way—and competition. Okay, yes, I AM disgruntled, but as things stand I am far happier that I am me and not Dan Brown, not Frank Conroy. I’m glad I’m not Dan Hoyt, too, but that’s because we never enjoy our own books the way we delight in the inspired works of others. And Hoyt is inspired, red hot, boiling—he’s a mad phalanx of lobsters with felt-once tip claws; and I’m going to let other reviews discuss his innovative moves—I’m going to tell you that I can’t remember the last time I came across so many memorable lines with such frequency, especially from a young first person narrator. It’s not only the descriptions, but the wisecracks, the attitude, the violently ambivalent truths of a man in the contracting idiocy of his time. Hoyt’s Neptune is an amazing literary creature, a narrative drive unto himself. And this is where I recall an obscure writer like Desani and his mad Hatterr and slide him into the review like an asshole, but I wouldn’t do that to Hoyt. I would do it to you, but not Dan Hoyt. The very notion is absurd—we need to shut the fuck up about other writers when we’re reviewing the current victim (every review is a violence done to the work of the author, every review). This may seem odd, but it is even about time we review the photos authors let their puppeteers attach to their books: and I’m damn glad a bald Hoyt with sleeves rolled up is looking at me, telling me he absolutely does not care what I think of his book. No sweater. No dog. No living room floor. Back to the book, the word choice is unparalleled, deft, but that goes without saying—if it wasn’t deft I wouldn’t be reviewing because I leave the reviewing of shitty books to others; no the word choice is consistently inspired: ‘burlap crackers’! See if you can top that. See if Joyce Carol Franzen can top that. It’s a work of literature and it has a plot, too, and you actually read it as fast as the narrator tells you to, tells you are, and unless you’re an asshole you will take your first origami lesson. As for the content of the book, I mean otherwise—the cover is great but for the five blurbs, all of which are right in praising the book, all of which fall short of sufficient praise, and each of which has at least one remarkable idiotic aspect (Listen to this shit: ‘A page-turner experimental novel.’ I would rip the head off anyone I caught putting that on my novel.)—the content of the book doesn’t matter in the least because the narrator is the book and it wouldn’t matter what he was going on about in his way. I probably should tip one of my Midwestern hats to Dan Hoyt, a lesser Pacino, phelt you can afford: the environment of his novel is up to date and survives, the characters what has been done to them, wires and everything…

Maybe one reason I like this book so much is that the narrator directly tells the reader a lot of what I think, but that passes because I have to get on with what I am writing—I like directly telling readers uncomfortable things and I don’t get to do it often enough. This book revels in it. I have spent far too much time writing for the one or two or three people who pop into mind as I write—P will like this, B will laugh at this, T will get this. The fact is, however, that we could not possibly have the detrital bloat of commodified cornholery that passes for literature without a plethora of morons not getting our books, not caring to get books, not advancing their selves through art, surrendering their selves lest art, merely paying lip service to art without even swallowing. Which brings me to my only problem with the book, not an uncomfortable one for me. I love great literature, and I read a lot of it, and I’m damn grateful for the current writers of it…But this is the first time I’ve ever read a book and felt that it might change my writing in some way in the future. It has an urgency that may finally lead to a necessary coherence in literature given the world that Arlt described is in its late menopausal stage. I might have to learn from Hoyt to maintain my relevance to myself. I might have to speed up to keep the urgency in sight. - Rick Harsh

https://rickharsch.wordpress.com/2017/12/15/this-review-is-not-for-amazon-dan-hoyts-this-book-is-not-for-you/

I did attempt to pass the time with a witty little novel, recently: something called This Book is Not for You by Daniel A. Hoyt on a little, unpronounceable press we’ll call Dzanc, if only we can ever learn how. This wild ride of a book reminds us that it’s not the tragedies that kill us; it’s the messes.

I must confess that the last time I encountered such a rude title with one sweeping, liquid gesture, I tossed it out of my twelfth-story window. But Mr. Hoyt’s voice sufficiently stilled my hand until I felt myself titillated and twitter pated and all around acidulated. So you see my confidence in my judgment is scarcely what it used to be. To that point, I cannot, with the slightest sureness, tell you if Mr. Hoyt’s new novel will sweep the country, like Main Street, or bring forth yards of printed praise…My guess would be that it might not, creeping forth like the finest small fish swimming in a school of sardines, but my God should it ever. Keep in mind that other guesses which I have made in the past year have been that Hillary would carry Wisconsin, that there might emerge a great dramatic critic for an American newspaper, and that I would have more than twenty-six dollars in the bank on March 1st, so I’ll leave Mr. Hoyt’s career in more capable and, hopefully, corporeal hands. You can certainly do your part by buying a copy.

I feel Daniel A. Hoyt’s little book is too tremendous a thing for praises. To say of it, ‘Here is a magnificent novel’ is rather like gazing into the Grand Canyon and remarking, ‘Well, well, well; quite a slice.’ Doubtless you have heard that this book is not pleasant. Neither, for that matter, is the Atlantic Ocean. On the first page we’re greeted with a stern warning by a Kansas anarchist – of all things – who finds it so nice he repeats it mercilessly throughout the title and the entire book. But that’s part of the fun, to keep touching on a refrain so that the whole band keeps swinging. Left to his own devices, our narrator, whose beloved mentor got herself murdered and whose satchel contains enough dynamite to blow up the entire English faculty at Kansas University, certainly doesn’t seem mentally sufficient for narrative responsibility. He doesn’t seem sufficient for very much at all, but Hoyt knows a capable mule when he spies one, and he saddles the idiosyncratic and inarticulate Neptune (I’m so very grateful Hoyt chose that name over Uranus) like a narrative beast of burden. Neptune perfectly illustrates the only dependable law of life – everything is always worse than you thought it was going to be.

The author finds a way to marshal the gritty, earthy and unseemly qualities of his narrator without succumbing to them. What we’re left with is a propulsive, profane, smart and very often hilarious work that compels you follow this ignoble Caliban the way we might follow that other low Midwesterner; Huckleberry Finn. As they say I say, A little bad taste is like a nice dash of paprika. - http://www.darrendefrain.com/this-book-is-not-for-you-daniel-hoyt/

Daniel A. Hoyt, Then We Saw the Flames: Stories, University of Massachusetts Press, 2009.

read it at Google Books

Read a story from this collection in the Kenyon Review

In this freewheeling debut collection, Daniel A. Hoyt takes us from the swamps of Florida to the streets of Dresden, to the skies above America, to the tourist hotels of Acapulco, to the southwest corner of Nebraska. Along the way, we encounter a remarkable group of characters all struggling to find their footing in an unsettling world.

Sometimes magical, sometimes realistic, sometimes absurd, these stories reveal people teetering on the dangerous edge of their lives. In "Amar," a Turkish restaurant owner deals with skinheads and the specter of violence that haunts his family. In "Boy, Sea, Boy," a shipwrecked sailor receives a surreal visitor, a version of himself as a child. In "The Collection," a father and son squander a trove of bizarre and fanciful objects. And in "The Kids," a suburban couple grasp for meaning after discovering children eating from their trash.

In each of these stories, characters find themselves challenged by the political, cultural, and spiritual forces that define their lives. With a clear eye and a steady hand, Hoyt explores a fragile balance: the flames―fueled by love, loss, hope, and family―shed new light on us. Sometimes we feel warmth, and sometimes we simply burn.

"Sharp, daring, and shot with moments of rare beauty, these stories grab you by the collar and refuse to let you go. Daniel Hoyt tears away the layers of our shared human experience to reveal the raw emotional truth at the core, and at the same time he uncovers the searing loneliness and desire that bind us together. This is a fearless and unforgettable book."―Julie Orringer

"A wonderful book that brings together thirteen stories that are odd bedfellows―now realist, now magical, now minimalist, now not. To read them is to wander untethered through Daniel Hoyt's highly developed imagination and to come away sometimes stunned, often thrilled, always amused, constantly surprised, and, from time to time, comforted. In a way, reading this collection is like changing channels on a very peculiar TV: the programs look different each from the next, but soon you realize that someone is controlling all of the programming, there are common threads running through every show."―Frederick Barthelme

"Variety is the spice of life, and Daniel A. Hoyt has a lot of spice. Then We Saw the Flames is a collection of short stories from one Daniel Hoyt, as he presents a fine compilation of short stories that go into a variety of topics, with the overlying themes of the challenges that everyone faces in their life. With plenty of entertainment crammed between the covers, Then We Saw the Flames is a great short fiction pick."―Midwest Book Review, Fiction Shelf

"Hoyt is a brave and capable writer and his collection provides an entertaining and exciting read."―North Dakota Quarterly

This is the way I like my fiction, when I get the feeling that no one else could write like this. That’s not to say that I think every story in this collection is high art. But unlike other collections I’ve read, these stories are tied together by a certain style. Each is quirky in its own way. But all of them could only have spilled out of one head. There are some normal (though low class) people doing mostly normal things, as in Last Call of the Passenger Pigeon. Well, except that an old man is teaching a troubled young boy, who has troubled young boy things on his mind like getting laid and stealing booze, how to make bird calls. How, in fact, to be the last person on earth who can make some of those bird calls. This would qualify as a really terrific story, except that ending took me away from the main character’s youth and into some coda-like passage that didn’t seem right. But don’t let that throw you. It’s well worth the read. Then there are some abnormal people doing abnormal things. In The Dirty Boy, a male character doesn’t shower for hundreds of days and becomes a minor media sensation. It’s thinly veiled sarcasm on our media saturated culture, with an under-toned parody of academia. It works, but again, the ending, this time only two lines so its effect is limited, seemed to me like that hangnail that keeps catching on your threads. Then there are the abnormal people we all are familiar with, such as terrorists, in this case caught in their own infinite loop. This was my favorite story, Black Box. Terrorists have hijacked a plane but the episode doesn’t end, all refreshments (to keep the passengers mollified) never run out, and the instruments in the cockpit don’t change. One of the hijackers "doesn’t believe in this overwhelming stasis." The passengers are not only not terrified, they are bored and have even gotten sarcastic. "Your wish is my command, Master of Disaster," one of the flight attendants says. Another cares no more whether they live or die. In my opinion, there’s more imagination and life on this plane than in any thriller with its requisite dark, menacing terrorists doing what you expect them to do. But here’s the even cooler part: One of the terrorists figuratively gives up and talks into the black box for posterity. Only the black box will outlast them, he says. Talking into the black box is all that’s left, the only place he can confess his sins, admit his failure, talk about his predicament. There’s rich irony and metaphorical static in this idea! The martyr seeking his eternal glory in suicide and death decides that an inanimate box will outlast him. This is the one story that I think has a terrific ending, too. In other stories, Hoyt includes immigrants, skinheads, orphans, and weird people who collect stuff. Don’t be put off by what I say about the individual story endings. We all know endings are so difficult to get right. Hoyt takes us on quite a journey with every story in this collection. You might be a tad wobbly pausing at each intermediate destination, but the overall experience is worth the price of the ticket. - Jason Makansi http://www.theshortreview.com/reviews/DanielHoytAndThenWeSawtheFlames.htm

The modern short story is sometimes so short that it does something less than tell a story. Glossing over the standard narrative arc, it catches a mood or a vignette and preserves it, like a bug under glass.The 13 offerings in " Then We Saw the Flames" Daniel A. Hoyt's short story collection, meet this definition. Hoyt, a professor at Baldwin-Wallace College in Berea, writes dark, cynical and nicely crafted tales. They glimpse a certain sad reality but rarely develop in a way that gives you pause.

Take Paul and Crystal in "The Kids," for example: They're married, fat and cheating their way through the Atkins diet. You don't hang with them enough to relate or sympathize; instead, they seem rather repulsive.

The couple is incensed with a bunch of young miscreants who repeatedly raid their trash. They go vigilante and catch them. Their actions create headlines they weren't looking for because the thieves turn out to be foster kids who forage other peoples' garbage cans to keep their hunger at bay.

Or, as the Family Services spokesman puts it on television: "Even the best systems possess a degree of failure."

Sadly, you never got a close look at the kids, either. So you shrug your shoulders at the inept bureaucracy (how is that new?) and move on. Hoyt writes with style and contempt, portraying a society besotted with celebrities but dismissive of everyone else.

In "Five Stories About Throwing Things at Famous People," he mocks this misplaced attention through the testimonials of five nobodies who find a sense of purpose in making contact, literally, with famous folks. In "Black Box," we hear from a 9/11-style hijacker whose route to fame and martyrdom includes a smart-mouthed flight attendant.

In "Maria," the former maid of Maria Callas hints at the sorrows of an ordinary life during an interview about the opera star. In "Amar," the title character is a transplanted Turk in Dresden besieged by skinheads. He's either a poster boy or a cliche -- you choose.

The best story in the collection, "Last Call of the Passenger Pigeon," is slightly longer than the rest. Here Hoyt gives himself the space to develop his characters to the point of sympathy. A hapless single mother sends her alienated teenage son on bird-watching expeditions with an old geezer intent on imparting what he knows. Hoyt figuratively and, in one case, literally gets under their skin. The storyteller seems less detached and more mature.

" Then We Saw the Flames" reveals a writer with style to burn and the potential to bring greater substance to his work. - Emry Heltzel

http://www.cleveland.com/books/index.ssf/2009/07/daniel_a_hoyts_debut_then_we_s.html

This Book Is Not For You by Daniel Hoyt claimed it was not for me, but this book was exactly what I needed. I likely won’t be the only one to compare the tone of the narrator to that of Holden Caulfield in my beloved Catcher in the Rye, that was the first thing that struck the right chord with me. I’ve missed that kind of chaotic narration. My head has been so far in the clouds, I forgot how exhilarating that kind of brutally honest stream of conscious messed up word vomit can be. And I loved every word of it.

It was quick, it was witty, it was all over the place yet never strayed too far from the core story. It was violent but it was also vulnerable. It will make you laugh and it will also make you cry. It will make you question everything you’re reading and everything you know.

This was a gritty coming of age story about a boy named Neptune who had been put upon and put upon, not unlike the tragic heroes he often references in the book. He fell in with the wrong crowd, he committed some wrongful deeds, and when the only person who was close to him, a mentally ill old school teacher, winds up dead, Neptune’s world starts to crumble and come into focus all at the same time.

This was chaotic and it was hard to follow, but it was also clear. It was a mess of contradictions and things that felt like lies but you’re constantly told are not lies. There was a dark overtone of lost youth, of kids who fall through the cracks and are just trying to get by, but there was also a hint of a love story, of broken people finding broken people and mending into some kind of whole.

Whatever this was, Daniel Hoyt may be partially right, this may not be for everyone, but this book was definitely for me. - citygirlscapes.com/2017/11/08/arc-book-review-this-book-is-not-for-you-by-daniel-hoyt/

story: The Inevitable

Interview with Daniel A. Hoyt

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.