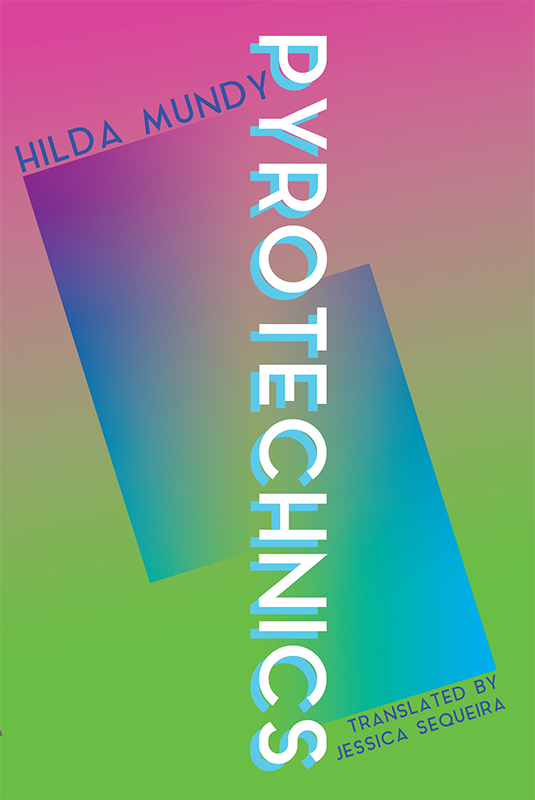

Hilda Mundy, Pyrotechnics: A Spineless Essay of Ultraist Literature, Trans. by Jessica Sequeira, We Heard You Like Books, 2017.

In Pyrotechnics: A spineless essay of Ultraist literature (1936), over the course of seventy prose poems, inspired by everything from magazine pop culture to high art, Mundy captures the noise of the metropolis, the effects of transformations in technology, the changes in sensibility and behavior she sees in her contemporaries, and the new professional aspirations of women.

When we talk about literary avant-gardes we tend to imagine a group of writers planning manifestos, participating in happenings, and editing books together. In many Latin American countries not everything was so collective; that was the case with Bolivia, where Hilda Mundy (1912-1982) was the only avant-garde writer (and one of the few female avant-garde writers on the continent). In the ’30s, when Mundy wrote, Bolivian poetry was still attached to forms of modernism from which the rest of the continent had moved on; it would have to wait until the end of the ’50s and start of the ’70s for renewal to occur. This may explain why the merits of the Oruro poet’s small body of work are only now being appreciated.

Hilda Mundy, the pseudonym of Laura Villanueva Rocabado, published just one book in her lifetime: ‘Pirotecnia’, subtitled “A spineless essay on Ultraist literature” (1936). The book was forgotten until 2004, when the Bolivian publishing house Ediciones La Mariposa Mundial printed a new edition of this highly valuable work. Mundy’s seventy prose texts attempt to capture the noise of the metropolis in the new century, the product of technological transformations and changes in sensibility and behavior. Her work comments on the fledgling modernity in the west of the country, including the possibility of alternatives to marriage and the new roles aspired to by women (“…she now feels herself a suffragist… chauffeur… aviator… engine driver… concert performer… boxer…”). Paradoxically, Mundy didn’t support the proto-feminist movements of her age.

The author sings her praises to electricity (“The hulking street light developed into an electric light bulb through a miracle of the Empress of Light…”) and plays with the changes in perspective during a journey in a tram: “On the platform with all the last minute passengers, two worlds appeared to me: travelers in the tram seated childlike facing one another, and the evasive artistic panorama of the city […] Science and art for the modest sum of twenty centavos!”. Her writing registers technological advances — the telephone, the public streetlight — and new urban settings — the theater, the sweet shop, the stadium — and admires them, while also showing doubt about the toll of progress. She writes of the automobile, for instance, that “those traveling in it accustomed to the landscape disappearing behind them, also long for the disappearance of humanity”. She accepts the modern cult of velocity, but prefers the calm movement of the tram to the frenzy of automobiles.

Literature may be predestined to failure, but one can discover “joy” in this.

At the age of only twenty-four and with such a promising work behind her, Hilda Mundy opted for silence. It would be logical to think she paid the price of many female writers of the period, who consumed by marriage and family (Mundy married two years after publishing ‘Pirotecnia’) didn’t enjoy the possibility of continuing a literary career. Without opposing that reading, the poet and critic Eduardo Mitre proposes another, reminding us that in the epilogue of her book Mundy mentions three types of artists. One of them is the “Genius who remains silent… because to remain silent is to make thought flourish on the route to perfection”. Mitre also points out that in her prologue Mundy suggests her texts are “fleeting fancies that represent nothing”. Literature, in the Dadaist gesture of the author, is a useless project that must be questioned.

After her “pyrotechnics” and “attack on logic” that “does without authenticity and borders the absurd”, the resulting gesture of the great artist is silence. In this, Mundy is as radical in her avant-garde ethos as Cesárea Tinajero in ‘The savage detectives’. Literature may be predestined to failure, but one can discover “joy” in this. - Edmundo Paz Soldán

http://themissingslate.com/2016/01/27/hilda-mundy-the-avant-garde/

Hilda Mundy (1912-1982) is the pseudonym of Laura Villanueva Rocabado, an avant-garde Bolivian writer who published just one book in her life, when she was twenty-four years old -- Pyrotechnics: A spineless essay on Ultraist literature (1936). In addition to Pyrotechnics, Mundy published a great deal of journalistic poetry, occasionally under pseudonyms, such as her personal impressions of the War of the Chaco -- but never another book.ardyoulikebooks.com/releases/pyrotechnics/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.