Juan Luis Martínez’s Philosophical Poetics is the first English-language monograph on this Chilean visual artist and poet (1942–1993). It has two principal aims: first, to introduce Martínez’s poetry and radical aesthetics to English-speaking audiences, and second, to carefully analyze key aspects of his literary production. The readings undertaken in this book explore Martínez’s intricate textual formalisms, the self-effacement that characterizes his poetry, and the tension between his local (Latin American, Chilean) aspect and the cosmopolitanism or transnationalism that insists on the global relevance of his work. Through his artistic engagement with a number of esoteric concepts—for example, his recuperation of pataphysical “logic” and Oulipian combinatorics, mathematical reasoning, Eastern thought, and the historical avant-gardes—Martínez creates a rigorous quasi-system of citation and erasure that is a philosophical poetics as well as a poetic philosophy. Juan Luis Martínez’s Philosophical Poetics thus addresses all major publications by this groundbreaking Chilean artist and poet in order to read his difficult, experimental texts by focusing on the tension he creates between philosophical, political, literary, and scientific discourses.

[This book] is the first study in English on the poetic production of Martinez. . . . Scott Weintraub succeeds with this study because it introduces the radical aesthetic of the poet in the English-speaking world and also carefully analyzes the key aspects of his literary output . . . We could say that the surprise text, text and unspeakable paradox text lines are synthesized and put into crisis the notion and coding of the poetry of Juan Luis Martinez. (A Contracorriente)

The title of his study is completely appropriate, for Weintraub convincingly demonstrates how Martínez creates a philosophical poetics, which is also a poetic philosophy. Weintraub’s book will be the starting point for all future research on this poet, for it brings together insightful commentary on the most recently published additions to his oeuvre, includes detailed attention to history of its publication, particulars of the poet’s communication and dialogue with others, as well as a very extensive bibliography of works by or about this intriguing writer. Aside from its important contribution as a very comprehensive approach to Juan Luis Martínez as an artistic and intellectual figure, Weintraub’s study offers multiple approaches to the Chilean’s work.... Scott Weintraub’s book uncovers many implicit dialogues of an author whose work readers may find ranges from tricky to impenetrable, by demonstrating how Martínez played hide and seek with a range of philosophical and aesthetic ideas from very diverse fields. The fact that this is the first such monograph to approach his work in English may expand his readership beyond those interested in innovative poetry and philosophy in Chile and open Juan Luis Martínez’s inter-artistic poetic production to the kind of transnational readership implicit in the work itself. (Revista de Estudios Hispánicos)

Juan Luis Martínez’s Philosophical Poetics is an interdisciplinary study of collage/assemblage art and poetry by the most infamous and hermetic member of the Chilean neo-avant-garde literary scene. This comprehensive study of cult figure Juan Luis Martínez (1942–1993) takes a comparative approach to the complex relationship between the visual arts, literature, science, philosophy, and mathematics in his work.

Breve selección poética de JUAN LUIS MARTÍNEZ

Juan Luis Martínez’s work is very well-known in Chile, despite the fact that only two books were published in his lifetime, La nueva novela (1977) and La poesía chilena (1978), and these in relatively small print runs. Martínez’s books were recognized for their radical experimentalism, for the connections they made between language and visual realms, for their humor, and their impenetrability—a quick glance through their pages that intersperse words and pictures with strange visual graphs and equations warned readers that these works certainly could not be approached with conventional ideas about lyric poetry. But in other ways, Martínez was continuing a tradition of interrogating the boundaries among the arts in Chile (I am thinking here of Nicanor Parra’s Artefactos published earlier in the same decade, 1972). One of the great strengths of Scott Weintraub’s approach to Martinez’s [End Page 790] work is his ability to situate him in Chilean, Spanish American, and broader intellectual traditions, for he reads this writer in terms of Huidobro, Borges, Rimbaud, and Pessoa (among other creative writers), yet also relative to “pataphysical logic, Oulipian combinatorics . . . mathematical reasoning, Eastern thought,” and the deconstructive ideas of Derrida (4). The title of his study is completely appropriate, for Weintraub convincingly demonstrates how Martínez creates a philosophical poetics, which is also a poetic philosophy.

In the book’s five chapters Weintraub demonstrates how Martínez employed his poetics to interrupt philosophy’s purported sovereignty over the literary, and how he carried this out through an “ethos of appropriation” and “uncreative writing” (5). Other elements in his poetic-philosophical strategy included continual self-effacement, marked by a yearning for marginality and the desire to write “the poetry of the other” (8). Martínez’s lack of self-promotion combined with the hermetic nature of so much of his work augmented the limited circulation of the books published in his lifetime. After Martínez died in 1993, three more works were edited and published posthumously: Poemas del otro: poemas y diálogos dispersos (2003), Aproximación del Principio de Incertidumbre a un proyecto poético (2010) and El poeta anónimo (2013). These, combined with a website that makes his highly conceptual, visual poetry more accessible, have stimulated renewed interest in Juan Luis Martínez’s poetry. Weintraub’s book will be the starting point for all future research on this poet, for it brings together insightful commentary on the most recently published additions to his oeuvre, includes detailed attention to history of its publication, particulars of the poet’s communication and dialogue with others, as well as a very extensive bibliography of works by or about this intriguing writer.

Aside from its important contribution as a very comprehensive approach to Juan Luis Martínez as an artistic and intellectual figure, Weintraub’s study offers multiple approaches to the Chilean’s work. Some of these are evident in the chapter titles, and I will discuss two of these here. Chapter two is “The Book within the Book: Math, Science, and Politics in La nueva novela,” and in it Weintraub demonstrates how Martínez’s 1977 work calls for a centrifugal reading, sending us outside of his text to create a dialogue between scientific and artistic fields. Some of these include links between Martínez’s poetry and formal logics as well as Alfred Jarry’s pataphysics. In an intriguing and well-researched section on the Boubaki group (a name adopted by a group of French mathematicians who published scholarly articles and poetry under one name) Weintraub connects their principles to those of mathematician and Oaoulipian Jacques Roubaud, as voices that form part of the philosophical underpinnings of Martínez’s work. As I read all of the myriad links Weintraub has uncovered (many of them far from common knowledge, even among academics), I wondered if his next project may be an annotated version of La nueva novela? What if it were to appear in digital form with hyperlinks... - Jill S. Kuhnheim

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/638413/pdf

If you are interested in contemporary Chilean Poetry, and you haven’t heard the name Juan Luis Martínez yet, then something is terribly wrong: you’ve been missing a lot. The good news is we are going to fix that right away.

Juan Luis Martínez was born in Valparaíso, in 1942. Son of the general manager of a reputable local steamship company, and a woman of Nordic origin coming from a very traditional family, he spent most of his life between the cities of Valparaíso, Viña del Mar, and Villa Alemana (Germantown!). As soon as he started high school, he abandoned his studies to embrace the bohemian lifestyle of the late ’50s in Valparaíso. A frequent visitor of all the legendary bars of that time in the harbor, like The Roland Bar, El Bar Inglés (The English Bar), El Yako, and the mythical Siete Espejos (The Seven Mirrors), Martínez was identified, by his family and peers, as a rebel kid. As a typical chico colérico (local version of the Greasers), he never returned to school, used to ride a scooter, wore his hair long (a particularly unusual feature for that period of time in Chile), and lived intensely his youth. As a self-taught poet, his recognized vast erudition came mostly from the many cultural influences that surrounded him in the cosmopolitan Valparaíso, and from his insatiable thirst for new readings.

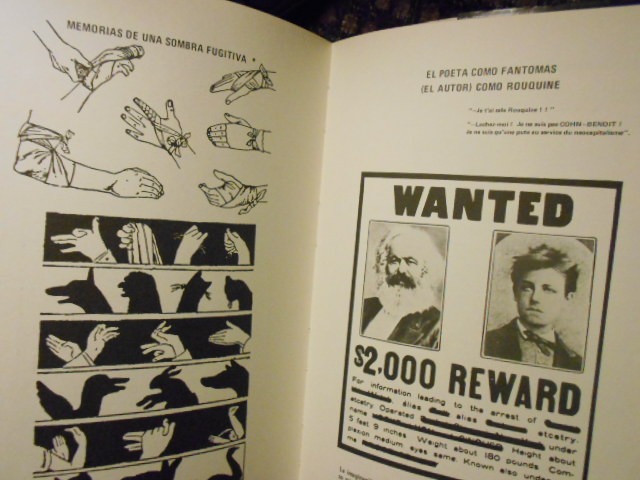

During his lifetime, Juan Luis Martínez got to publish just two books. In 1971, he submitted his first book of poems to the Chilean press Editorial Universitaria. After two years of thoughtful review the publisher rejected Pequeña Cosmogonía Práctica (Small Practical Cosmogony) because it was impossible for them to classify. A frustrated Martínez finally decided to self-publish the manuscript in 1977, changing the title to La Nueva Novela (The New Novel). Listed as one the most enigmatic books of Chilean literature, labeled as the first object-book in the history of Chilean poetry, and considered a seminal work, La Nueva Novela stands as an iconoclastic and disruptive book of poetry. Built as an endless maze of quotes, based on a complex system of literary, philosophical, artistic, and scientific references, its fragments, even though they are constantly aiming to different directions, still draw together a coherent poetic unit, where skepticism, irony, and humor are protagonists. Using strategies such as the eradication of the traditional notion of authorship, appropriation, plagiarism, and recontextualization, Juan Luis Martínez perfectly embodies in advance all the premises of today’s conceptual writing. Despite the fact that La Nueva Novela had a poor and restricted circulation, it succeeded in becoming a foundational book, opening the doors of the neo-avant-garde in Chile, and forging an interesting legacy of experimental writing, which still prevails.

In 1978 he published La Poesía Chilena (Chilean Poetry), an object-book that included a small bag of dirt from Chile’s Central Valley, death certificates of the greatest Chilean poets (Gabriela Mistral, Pablo Neruda, Pablo de Rokha, and Vicente Huidobro), miniature Chilean flags, and blank library cards. There is no trace in the entire book that Martínez had written anything in it. What's more, some rumors say that Martinez kept an original of this book, a sort of master copy, which he continued to add to every time a Chilean poet passed away.

These two books were personally designed and edited by Juan Luis Martínez, and it was also Martínez himself who guarded their distribution, since for the poet it was important to know who had access to his work.

Before he died, Martínez left specific instructions to his wife regarding what to do with his unpublished material: she should burn every single paper, nothing should remain. However, ten years after his death, his widow contacted a local editor with an urgent message; she had found a manuscript left by the author that should be published. That is how in 2003 Ediciones UDP published Poemas del Otro (Poems by the Other), a collection including a short manuscript titled Poemas del Otro, from which the book takes its name, eight little-known poems found in different publications, and a small set of interviews, which includes a conversation with the French philosopher Félix Guattari.

When nobody was expecting any new publications by the poet, in 2010 appeared Aproximación del Principio de Incertidumbre a un Proyecto Poético (Approximation of the Uncertainty Principle to a Poetic Project) edited by the poet Ronald Kay and published by Galería D21. Made of 28-ringed xerox copies, which supposedly belonged to a “work of long gestation,” finished between 1991 and 1992, this book is composed exclusively by visual poems that strike the reader in a way that is similar to the impact of semiotic writing. There is also an evident and strong influence of the trigrams of the I Ching.

And finally, again contradicting the instructions given to his widow, ten years after the publication of Poemas del Otro, exactly twenty years after the death of Juan Luis Martínez, another posthumous book appears. This time published in São Paulo, Brazil, by Cosac & Naify and edited by Pedro Montes Lira, in collaboration with the curator of the Bienal de Arte de São Paulo, Luis Pérez-Orama, El Poeta Anónimo (o el Eterno Presente de Juan Luis Martínez), The Anonymous Poet (or the Eternal Present of Juan Luis Martínez) is an overwhelming assembly of collages, altered pictures, found images, found texts, and cut-ups of diverse origin. As he told Felix Guattari, he finally managed to compose a work where any single line included in the book belongs to him. El Poeta Anónimo is a book that more than being read is to be seen. Found poetry or a kind of poetic readymade, the book used uncountable different sources in many languages. From obituaries, comics, anthropological essays, lit theory, art theory, art history to prayers, litanies, news, advertising, etc. As the editor noted, the book is nothing but nostalgia for happiness strategically turned into poetry.

Unfortunately, this extraordinary and appealing work hasn’t been translated entirely into English yet. Maybe the first, and for a very long time the only translations available of Juan Luis Martinez’s work, were the ones included by Steven White in “Poets of Chile, a Bilingual Anthology 1965–1985”, an edition of two generations of writers who began to publish prior to and after the 1973 military coup. A few other translations appeared in “The Critical Poem: Borges, Paz, and Other Language-Centered Poets in Latin America,” by Thorpe Running, published in 1996 by Bucknell University Press. And recently Mónica de la Torre has presented her own translations in s/n and Zoland Poetry.

In 2000, the filmmaker Tevo Díaz released Señales de Ruta (Road Signs), a sharp and noteworthy documentary, about the work and poetics of Juan Luis Martínez. Mixing sublime images of the Chilean landscape with some pages of La Nueva Novela and La Poesía Chilena, and including interviews with key personalities of the Chilean literary scene (such as Volodia Teitelboim, Armando Uribe, and Miguel Serrano), Díaz managed to put together a very clever film without loosing sight of all the mystery and mystique that always surrounded the figure of the poet. (Find the technical specifications here). - CARLOS SOTO-ROMÁN

http://jacket2.org/commentary/nothing-real

The recent edition of La nueva novela puts the poet who aspired to "radiate a veiled identity" back into circulation. This article gives an account of unpublished aspects of the life of Juan Luis Martínez, shows his rejections and affiliations with Chilean poetry, and reveals the obsessive methodology of work that gave body to a work that is poetic and philosophical at the same time, and that with its unique humor and sense of absurdity, it continues to baffle readers of the 21st century.

Juan Luis Martínez después del silencio

La nueva novela, Publicaciones D21, 2016, 152 páginas, $70.000 (disponible solo en galería D21).

Finding (the other) Juan Luis Martinez (pdf) or here

Juan Luis Martínez and his double: The ethics of dissapearance or writing the other's work

CARLOS SOTO-ROMÁN

There has been some relevant news about Juan Luis Martínez’s work circulating for a while. Scott Weintraub, an academic of the University of New Hampshire, has published in Santiago, Chile, and the US two important books of essays discussing a crucial discovery concerning Martínez’s posthumous publications. During his research, Weintraub found that the initial poems of “Poemas del Otro” had been written by another poet called Juan Luis Martinez, this one from Swiss-Catalan origin. “Poemas del Otro” was published in Chile in 2003, ten years after Martínez’s death. The lyric nature of the poems included in the edition surprised the general public, mostly because they bore no resemblance to the work displayed by Martínez in his seminal work “La Nueva Novela,” but the amazement was not enough to raise suspicions. Ten years later, in 2013, “El poeta anónimo” was published in Brazil. In the middle of the book is possible to find some specific clues that led Weintraub to realize that this apparent plagiarism was more a well-plotted and complicated literary game or hoax. Find a conversation with Scott Weintraub about his fascinating discovery below. If you are not familiar with Juan Luis Martínez and his work, read a previous article here. You can also find Scott Weintraub’s full account of his literary adventure following Martínez’s clues here.

You were conducting some research focused on another Chilean poet (Vicente Huidobro) when you saw La Nueva Novela for the first time. What happened to you? Why did you decide to radically change the topic of your investigation?

At the time I was editing a book on Huidobro and also revising my dissertation (on poetry and politics in Néstor Perlongher, Osvaldo Lamborghini, and Raúl Zurita), with an eye to turning it into a book. However, when I first read La nueva novela in June of 2008, like many readers of Martínez I quickly became obsessed with its labyrinthine textualities and its absurdist (yet rigorous) writing practices. I initially planned to incorporate a discussion of Martínez’s ethic of disappearance into my revised dissertation. But after realizing that there was so little engagement with his work in English, I decided, perhaps foolishly, that I would write the first English-language monograph on Martínez. Six and a half years later that book is finally finished: Juan Luis Martínez’s Philosophical Poetics was published by Bucknell University Press in December 2014.

Tell us about your discovery. How did you realize Juan Luis Martínez didn’t write Poemas del Otro? What clues did you follow and what is the importance you think this discovery has for Martinez’s work, and for the approach of current studies about him?

In October 2013 I was revising my completed manuscript on Juan Luis Martínez when I was struck by the inclusion of a review of a book titled Le Silence et sa Brisure (Silence and Its Breaking) in Martínez’s xeroxed-collage 2012 work The Anonymous Poet (or Juan Luis Martínez’s Eternal Present). The review was published in 1976 and describes a work by a Swiss-Catalan poet also named Juan Luis Martinez (with no accent mark); the following page of The Anonymous Poet is comprised of a facsimile of a card catalogue entry for Silence and Its Breaking, taken from the collection of the French-Chilean Institute of Valparaíso (which no longer exists). I subsequently used the online library database WebCat (with expanded search parameters) to find out more about this book, which was published in Paris in 1976 by the now-defunct Editions Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Out of curiosity I requested Le Silence through interlibrary loan and my surprise when I received it could not have been greater. If the initial poems had a ghostly familiarity to them, they should have: I was shocked to realize that the seventeen poems contained in Silence and Its Breaking were very nearly exact translations of the first section of the Chilean Martínez’s book The Other’s Poems, published posthumously some twenty-seven years later.

Upon recovering from my initial surprise, my first impression was that these poems must have been written in French by the Chilean poet, which meant that Poemas del otro (2003) was composed of translations to Spanish of these poems, originally published in French in 1976. Alternatively — as Chilean journalist Pedro Pablo Guerrero (of El Mercurio) suggested to me via email — I wondered if Martínez had written these poems in Spanish and sent them, clandestinely to a Chilean friend living in exile in Paris during Pinochet’s dictatorship. With nearly half of the Chilean intelligentsia residing in Paris following the bloody 1973 coup d’état, Martínez very easily could have entrusted the poems and their translation to an exiled compatriot. Or, might the Chilean Martínez have discovered the Swiss-Catalan Martinez and together they collaborated on these poems (as a kind of Situationist joke or prank)? Perhaps “Juan Luis Martinez” was an invention or avatar of Juan Luis Martínez, an orthonym that recalled Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa’s extensive use of heteronyms.

Only adding to the ominous nature of this find was the fact that the Swiss-Catalan Martinez’s final book was published in 1993, the same year as the Chilean poet’s death. A few years prior, Martínez had published two of these ostensibly political poems prior to the plebiscite that would put an end to Pinochet’s dictatorship. During his only travel outside of Chile — invited to Paris in 1992 as a part of a group of Chilean writers — he read the poem “Quién soy yo” (“Who I Am”) as his self-introduction, which, as I discovered, is a translation from what appears to be the original (French) text. In this way, Martínez could only self-identify by way of the other Martinez’s words, which rang true with the Chilean poet’s ethic of literary disappearance and self-erasure as an author.

I felt relatively confident that Juan Luis Martinez existed without having any hard evidence to support this assertion. After all, I knew that the Chilean Martínez read French but needed a translator when psychoanalyst and philosopher Félix Guattari visited his house in Villa Alemana in 1991. I also doubted that a well-known bande dessinée (Swiss adventure comics) author such as Daniel Ceppi — with whom Martinez collaborated on two occasions (Ceppi adapted Martinez’s short stories) — would work with a Chilean poet whose French was not up to the task. Plus I just did not see Martínez as being interested in something like bande dessinée, even as part of an elaborate, multi-decade hoax.

In the face of these uncertainties, in July 2014 I published a short book in Chile called La última broma de Juan Luis Martínez: no sólo ser otro sino escribir la obra del otro (Juan Luis Martínez’s Final Trick: Not Only Being Other but also Writing the Other’s Work), which summarized my findings and put forth the theory that the Chilean poet translated and appropriated extant works by the Swiss-Catalan Martinez. After a transcontinental search for the “other” Martinez, I was able to confirm this. It’s a long story …

Regarding the importance of my discovery for Martínez studies, the “Martínez affair,” I believe, is less important for what it highlights about either JLM; rather, it is significant for the way it speaks to the question of originality in literature, the role of translation and also the humanity of writing itself as an inhuman force. After all, where Martinez has brought out aspects of Martínez’s writing through their communication across time, languages, and national traditions — and vice versa — what brings them together becomes clearer even as the identification of the original and the copy becomes more and more problematic and uncertain. As Juan Martinez himself asserted, this relation or synchronicity implies a transcendence beyond a mere joke or trick: in what he described as “Martínez’s literary suicide” we find the radical (Chilean) poet’s reinscription as an author in the face of the impossible challenge of disappearing behind a veil of words. And this would have been “the perfect crime,” according to Juan Martínez, had The Other’s Poems and The Anonymous Poet not insisted on the poet’s necessary failure to disappear absolutely. In the end, this is the punchline of Martínez’s final trick: becoming even more Martínez in poems written by another Martinez.

Your book will be the first comprehensive study about Juan Luis Martínez in English. Despite the attention Martínez has been getting in the last years in the US, why do you think no one else took on this author before?

Cecilia Vicuña and Ernesto Livón-Grossman, the editors of the Oxford Book of Latin American Poetry, call Martínez “the best-kept secret of Chilean poetry — according to almost all present-day critics” (452). This is, in part, related to the limited circulation of his artist’s books: the 1977 edition of La nueva novela (500 copies) is only held by one library in the US, whereas the 1985 edition (1,000 copies) is held by twenty-five libraries (as of May 2014). La poesía chilena (500 copies), however, appears in the catalogues of a mere seven libraries in the US. It is also very difficult to purchase Martínez’s early work; since few copies exist on the secondary market (even in Chile), the curious reader who wishes to purchase a copy of the 1985 edition of La nueva novela must arrange to have onces (“elevenses,” which consists of tea and snacks) or coffee with Martínez’s widow, Eliana Rodríguez, in Viña del Mar or in Villa Alemana, in order to explain his or her motives for wanting to own one of the very few remaining copies of the book — which sells for the set price of $200, as established by Martínez towards the end of his life.

In a larger context, there have been few in-depth, theoretically rigorous treatments of Martínez’s writing, even in Spanish; descriptive and journalistic readings tend to predominate. As Matías Ayala suggests, “La nueva novela se presenta, entonces, como una especie de laberinto semántico: las redundancias y variaciones producen una desorientación que resiste la interpretación. Esta es una de las razones de por qué la crítica de La nueva novela suele expresar sorpresa por lo singular del libro pero, asimismo, se limita a enunmerar esas curiosidades” (“The New Novel presents, then, as a kind of semantic labyrinth: its redundancies and variations produce a disorientation that resists interpretation. This is one of the reasons why critics of The New Novel tend to express surprise about the uniqueness of the book, but at the same time limit themselves to enumerating its curiosities”); from Lugar incómodo: Poesía y sociedad en Parra, Lihn y Martínez (Uncomfortable Place: Poetry and Society in Parra, Lihn and Martínez [Santiago: Ediciones Universidad Alberto Hurtado, 2010], 166–67). This tendency towards merely summarizing the content of difficult literary works is perhaps indicative of a reluctance to engage with hermetic poetry, giving rise to criticism that “reads around” texts that otherwise demonstrate resistances to reading strategies that would seek to “master” a given text, such as hermeneutics, historicism, etc.

Roberto Bolaño once said about Martínez that he was the only Chilean writer that had “read” Duchamp properly. Juan Luis Martínez, as well as other Latin American writers/artists (such as Ulises Carrión and Guillermo Deisler) employed the same premises and materialities of conceptual writing but way before conceptualism was known. What are the tensions and dialogues you think can be established between these two?

We might say that Martínez wrote the novel that Bolaño failed to write — The New Novel (a book of collages and poems) — insofar as Bolaño, the failed poet, turned to prose as a more lucrative source of income for his family. For both poets their greatest success was their greatest failure, in a way: Bolaño would reemerge as the (bestselling) novelist hailed as the “Latin American voice of his generation” (or something like that); Martínez would realize his own poetic apotheosis — “not only being other but also writing the other’s poems” — by appropriating the other JLM’s poetry, only to reinscribe the figure of the author in his failure to completely disappear amidst a galaxy of signifiers.

It is also noteworthy that Bolaño himself pays homage to Martínez numerous times: a main character in 2666 is named (Inspector) Juan de Dios Martínez, after Bolaño called Juan Luis “una pequeña brújula perdida en el país” (“a compass lost in the wilds of Chile”) in Distant Star (trans. Chris Andrews [New York: New Directions, 2004], 48) and referred to Martínez’s work as sort of a “perfect study” of Duchamp in Between Parentheses (New York: New Directions, 2011, 96). In a recent article, Alejandra Oyarce Orrego discusses the relationship between Bolaño’s Los detectives salvajes (The Savage Detectives) and Martínez’s La nueva novela, and mentions several references to Martínez in other texts by Bolaño:

Bolaño reconoce, de manera explícita, la vinculación con el autor de LNN [La nueva novela] cuando destaca a Juan Luis Martínez entre los seis tigres de la poesía chilena, junto a Bertoni, Maquieira, Muñoz, Lira y a, él mismo, en el cuento “Encuentro con Enrique Lihn,” que forma parte de Putas asesinas (Bolaño, 2001, 219). Del mismo modo, en LNN vemos: “Dados dos puntos, A y B, SITUADOS A IGUAL DISTANCIA UNO DEL OTRO, ¿cómo hacer para desplazar a B sin que A lo advierta?” (Martínez, 1977, 11). Treinta años más tarde, en el texto “EL INSPECTOR” incluido en La universidad desconocida, leemos: “Tome usted la única ruta, desde el punto A hasta el punto B, y evite perderse en el vacío” (Bolaño, 2007, 171). Por último, en el texto “Unas pocas palabras para Enrique Lihn” que forma parte de Entre paréntesis, Bolaño parafrasea uno de los fragmentos incluidos en las solapas de LNN, en su afirmación “La literatura ha estado a la altura de la realidad. La famosa rea, la rea, la rea, la rea-li-dad.” (Bolaño, 2008 [2004], 202)

… Bolaño explicitly recognizes his connection to the author of The New Novel when he singles out Juan Luis Martínez as one of the six tigers of Chilean poetry, together with [Claudio] Bertoni, [Diego] Maquieira, [Gonzalo] Muñoz, [Rodrigo] Lira and himself, in the short story “Encounter with Enrique Lihn,” which appears in the book Murderous Whores (Bolaño, 2001, 219 [short stories from Putas asesinas appear in English in Last Evenings on Earth (2006) and The Return (2010)]). Similarly, in The New Novel we read: “Given two points, A and B, LOCATED AT AN EQUAL DISTANCE FROM ONE ANOTHER, how do you move B without arousing A’s awareness?” (Martínez, 1977, 11). Thirty years later, in the text “EL INSPECTOR,” included in The Unknown University, we read: “Take the only path, from point A to point B, and don’t get lost in the void” (Bolaño, 2007, 171). Finally, in the text “A Few Words for Enrique Lihn,” which can be found in Between Parentheses, Bolaño paraphrases one of the fragments included in The New Novel’s cover flaps, in his affirmation that “literature has measured up to reality. The famous re, the re, the re, the re-al-it-y”

(From “Cortes estratigráficos en la crítica y en la obra de Roberto Bolaño” [“Stratographic Cuts in Criticism and Work by Roberto Bolaño”], Acta literaria 44 [I sem. 2012]: 30. My translation, save this last quote from Between Parenthesis, which can be found in Natasha Wimmer’s translation of the essay “A Few Words for Enrique Lihn” [New York: New Directions, 2011, 218].)

Finally, why is it important the English-speaking reader know about Juan Luis Martínez’s work?

Firstly, there are literary-historical motivations related to exploring the Chilean scene of writing in the 1970s and 1980s (for example, the context of writing under dictatorship, experimental and conceptual poetics in Latin America, etc.). This also includes a focus on the ludic strain of the Chilean neo-avant-garde (as Marcelo Rioseco has convincingly argued in the context of Martínez, Rodrigo Lira, and Diego Maquieira, the most direct poetic descendants of Nicanor Parra). More importantly, however, there are few artists or writers from Latin America who have so adeptly interrogated the relationship between word and image in poetry, while at the same time developing a rigorous, yet absurdist philosophical poetics (which for Martínez, was a poetic philosophy). Martínez’s poetic philosophy is exemplary among contemporary texts written under the Chilean dictatorship in its radical conceptual “uncreativity,” vis-à-vis the complex formalisms he so carefully employs. La nueva novela, La poesía chilena, and El poeta anónimo, in particular, are intensely political in their critical self-reflexivity as Chilean books that very clearly attempt to situate themselves outside of Chilean intellectual-poetic space, through the erasure of the author as well as their radical use of appropriation, bricolage, citationality, translation, and interdisciplinarity. Martínez’s groundbreaking work is the site of a unique and unresolved encounter between the poetic (the poet) and the philosophical — in this case, both the professor of philosophy and the philosopher (as poet), to paraphrase Chilean philosopher Patricio Marchant. And as Cuban poet and essayist José Lezama Lima has argued — in the very beginning of his essay American Expression — “Only that which is difficult is stimulating.” I have found no more difficult — or stimulating — writer in the whole of contemporary Latin American literature than Juan Luis Martínez.

https://jacket2.org/commentary/juan-luis-mart%C3%ADnez-and-his-double

In LALT 1.4 (October 31, 2017) I published an essay detailing some of the controversies involved with Chilean poet Juan Luis Martínez’s (1942-1993) posthumous body of work. This literary detective story began in 2013 with my discovery that the first publication after Martínez’s death —a book of mostly unpublished lyric poems and interviews called Poemas del otro (2003)— was largely an unattributed translation of a book titled Le Silence et sa brisure (1976), written by a Swiss-Catalan poet also named Juan Luis Martinez (without an accent mark). Insofar as Martínez repeatedly insisted that he had not written the poems (“fueron escritos por el otro”) in truth he meant the other Martinez. As I argued in my books La última broma de Juan Luis Martínez: No sólo ser otro sino escribir la obra de otro (Cuarto Propio, 2014) and Juan Luis Martínez’s Philosophical Poetics (Bucknell UP, 2014), the brilliant conceptual logic of this “writing-as-translation” project made Martínez even more Martínez in poems written by another Martinez.

However, on July 7, 2017—on the 40th anniversary of the publication of La nueva novela [The new novel], and on what would have been Martínez’s 75th birthday—the Martínez family and patron Pedro Montes released a facsimile edition of his masterpiece La nueva novela, which included hand-written comments ostensibly made by the author. This edition of 300 copies sold for 150.000 Chilean pesos (approximately $250) and contains numerous annotations in Martínez own hand—or so it seemed. In the summer of 2018, however, a controversy emerged regarding the authenticity of these hand-written comments. The author of these annotations was allegedly not Juan Luis Martínez, but rather a former literature student named Ricardo Cárcamo, who maintains that he is the true author of the hand-written notes reproduced in the 2017 edition of La nueva novela. This interview took place on September 22, 2018. Read more here: Ricardo Cárcamo: "I wrote the annotations in the 2017 edition of The New Novel": A Conversation with Scott Weintraub

French translation:

https://www.undernierlivre.net/juan-luis-martinez-le-nouveau-roman/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.