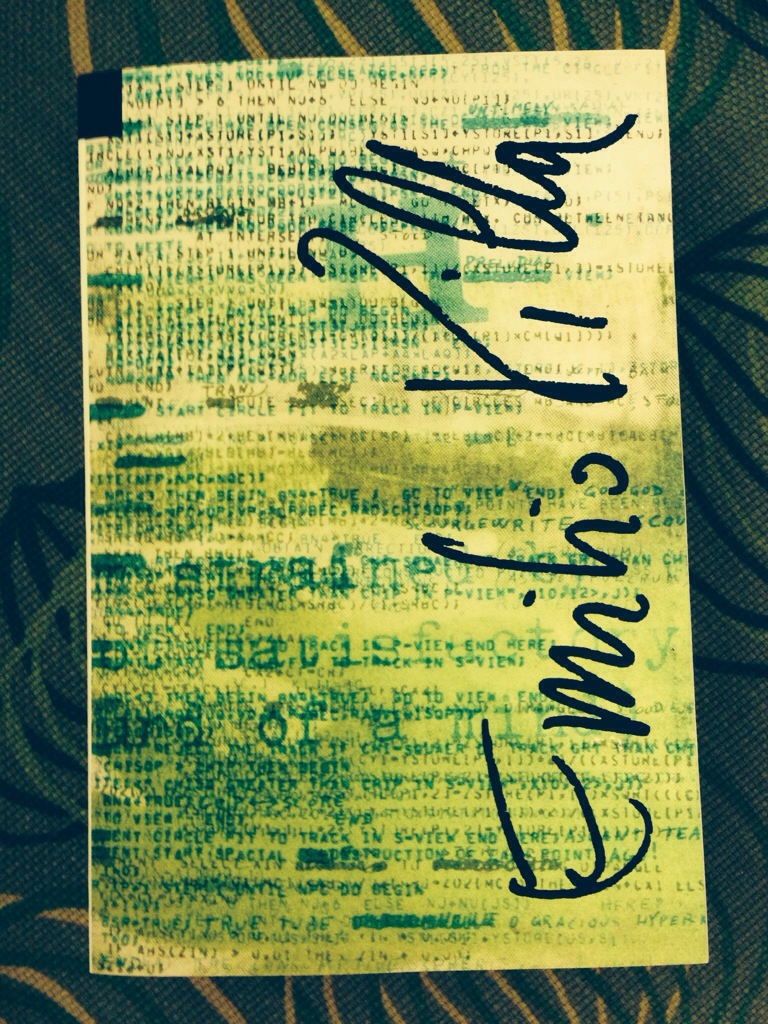

Emilio Villa, The Selected Poetry of Emilio Villa,

Trans. by Dominic Siracusa, Contra Mundum

Press, 2014.

excerpt (pdf)

While Emilio Villa (1914-2003) was referred to as Zeus because of his greatness and Rabelais because of his mental voracity, for decades his work remained in oblivion, only recently surfacing to reveal him to be one of the most formidable figures of the Italian Novecento, if not of world culture. His marginalization was in part self-inflicted, due to his sibylline nature if not to his great erudition, which gave rise to a poetics so unconventional that few knew what to make of it: a biblicist who composed experimental verse in over ten different languages, including tongues from Milanese dialect and Italian to French, Portuguese, ancient Greek, and even Sumerian and Akkadian. As Andrea Zanzotto declared, "From the very beginning, Villa was so advanced that, even today, his initial writings or graphemes appear ahead of the times and even the future, suspended between a polymorphous sixth sense and pure non-sense." In merging his background as a scholar, translator, and philologist of ancient languages with his conception of poetics, Villa creates the sensation that, when reading his work, we are coming into contact with language at its origins, spoken as if for the first time, with endless possibilities. Whether penning verse, translating Homer's Odyssey, or writing on contemporary or primordial art, Villa engages in a paleoization of the present and a modernization of the past, wherein history is abolished and interpretation suspended, leaving room only for the purely generative linguistic act, one as potent today as it was eons ago. This volume of Villa's multilingual poetry ranges across his entire writing life and also includes selections from his translation of the Bible, his writings on ancient and modern art, and his visual poetry. Presented in English for the very first time, The Selected Poetry of Emilio Villa also contains material that is rare even to Italian readers. In adhering to the original notion of poetry as making, Villa acts as the poet-faber in tandem with his readers, creating une niche dans un niche for them to enter and create within, as if language itself were an eternal and infinite void in which creation remains an ever possible and continuously new event.

As the universe expands and its galaxies grow further apart with a speed proportionate to their respective distances, so does the linguistic universe of Emilio Villa. - Adriano Spatola

Who are the greatest Italian poets? Ask the most turned-on and tuned-in anglophone literary heads you know and you’ll get a rich list indeed, including Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio, Montale, Pavese, Leopardi, de Palchi, Calvino and Merini. Mama Mia, some wise guy might even throw in Vinnie Barbarino, but he, like Dominique Wilkins, is more accurately “poetry in motion.”

Does poet, scholar, translator, philologist and art critic Emilio Villa (1914-2003) deserve a spot on that roster? Dominic Siracusa, who has meticulously edited and helpfully annotated this volume in the face of the distinct challenges of Villa’s obscurity, his temporary exile from Italy in Central America, and his penchant for destroying his own work, would definitely argue in the affirmative.

Siracusa’s thesis, as presented in his introduction, is that placing Villa in the canon of 20th century Italian poetry radically disrupts the way we think about the Italian avant-garde. Without pretending to read Italian, this humble critic would concur. Because even when we place Villa’s work in the context of poetry as a human endeavor, it prefigures much of what would come to seem innovative about American poetry in the second half of the 20th century.

But that’s not really what’s interesting and finally rewarding about this book. Villa is zany: energizing and enervating by turns, emotionally and intellectually. His is a polyphonic voice. From high to low diction, Italian to English to Latin to Spanish to French to Sumerian to Akkadian, to drawings and photographs — sometimes all on the same page — Villa’s concept of “poetry” was all-encompassing.

But it didn’t necessarily start out that way. One thrill of this book is the wild contrast between Villa’s early work and his last. If, as Ilya Kaminsky suggests, great poetry begins in elegy and ends in praise, Villa’s body of work is great poetry in the sense that it begins in elegy and ends in praise of the malleable force of language. But such strictures are not necessarily relevant to a mind as iconoclastic as Villa’s. Here’s part of an early poem, “Medieval Town,” published in 1934:

A people of grim and holy thoughts,

Like old angels hanging from the sky,

Rolls across the bells’ waves.

Melancholy pervades Villa’s first book, Adolescence, but Villa’s work quickly thickens and grows stranger. Yes, but Slowly, published in 1941, is a departure from Villa’s earlier poetry and one that seems to cross the best of Ginsberg and Beckett. The collection is a turning point in the development of Villa’s style from the personal to something more experimental and expansive. Here’s part of the title poem:

we wait, patience will come, let’s get to the thing:

it will come when in the evening in the little town

where the incandescent clouds of dried meals cross off shore

and the shouts of barn dances or halls, in a winy

prose, when spring tenderly milling between false notes

and musically will spread across the colored hemisphere,

in great handfuls the grasshoppers and grain and fountains

of the universal grain and the cornel tree, and venus

supreme venus and an inimitable light of iridium […]

A multi-linguist who worked in numerous languages in his native Italy before moving to Brazil in the 1950s, where he became involved with Concrete Poetry, which would deeply influence today’s Vispo movement, Villa was complex and original from the start. But reading chronologically through these poems, one sees a rapid shift toward the avant-garde. This development seems to have been at least partially sparked by World War II, as is evident in the brilliant poem, “1941 Piece,” which begins with a description that could be an ars poetica before moving in the second stanza to the cynicism that injects Villa’s otherwise intellectual poetry with feeling and humor:

It could be

that on any given

day air would travel

half-heartedly through the air,

maybe, but if Lake Garda fails to recover in time

all the dust eaten by cyclists in meaningless races,

& kilometers that don’t count, good for nothing […]

Villa’s poetry is often as ethereal as air blowing through air, or as he writes a few lines later, an “ephemeral vase of air.” But elsewhere in this poem, which stands out for its connection to historical events, Villa is stunning in his visual precision, as when he writes about “the breath…”

of foreign fodder, and the air filled

with a stew of local beer, and the change

of musical coins across the zinc counter, will touch

the firmament with frosted hands: and then

some agate marbles concealed in the panic snore

of those poplars will serve as lamps or blinds

When Villa writes about “the earthly dream / where the stones of Europe mature,” his vision of poetry in the midst of a World War crystallizes. This poem, which comments obliquely on the situation in Europe and Italy during World War II, is one of the last in the book that feels grounded in a physical subject. After 1950, when Villa published his collection Yeah but After, his poetry is a cacophony. This book and several following are printed horizontally rather than vertically, so one has to turn the book on its side to read the poems. At this point all the elements of language — its sound, its sense, and its image — become more pressing realities than the physical world.

In much of this mid-career poetry, Villa sounds like Fernando Pessoa if he could have written in all of his voices at once. This is code-shifting at its most vibrant:

seed in the tracks at the end of the line under the rotten ties

seed on the cobblestone of the capital

a grain on the sparrow’s tail

a proton (in the parlance of our times) a quantum bloated with shade

in the isotope

or (let’s suppose) a bacillus aestheticus subtillimus

in the wolf’s maxillary membrane or the anal

orifice of the whale

a seed (as we say around here) that leavens, of Justice […]

This is poetry that is smart, sensitive, and hard not to enjoy. When Villa is at his most inventive, he can swerve between the voice of Chaucer and a Milanese chancer in the dark alley of one line.

In Da Verboracula, published in 1981, drawings and charts mingle with words, vying for the attention of the reader, who is now also partially a viewer. The latter part of this collection feels utterly contemporary, as in still strange, like a combination of the New York School and the Language Poets. And here we see how Villa’s work developed along the same lines as the poetic avant-garde we generally consider American. This is from “Poetry Is,” written around 1989:

poetry is to forget

forgetfulness

poetry is to se-parate self from self

poetry is what’s completely left out

poetry is emptying without exhausting

poetry is constraint to the remote,

to the not yet, the not

now, the not here,

the not there, the

not before, neither not after,

nor not now […]

It is certainly Villa’s deep allegiance to the avant-garde and the experimental that have kept him in obscurity. Siracusa states that the poet is still relatively unknown even among Italian readers. His entrance into the canon enriches and complicates the way we think about poetry in both Italian and English.

Readers of Czech poetry will see a stylistic connection between Villa and the exiled Czech poet Ivan Blatný, whose late work also moves among several languages. As such, Villa — like Blatný — is a scholar’s dream, relatively untouched and truly complex. Contra Mundum is establishing themselves as a clearing house for Villa’s work, also publishing his Selected Writings as well as his translation of The Hebrew Bible.

It is important to note that passion shines through Villa’s great erudition and at times astringent avant-garde sensibility, and this is what differentiates him from many devoted practitioners of experimental anglophone poetry. His most familiar touch is a shock:

windows are a seed among headlights: and I

sow breath and great goodtime, and you

walking up and down the arteries of town;

and I make ragged comparisons, and you carry

the stingy and melancholy beauty within the red shade

of still being beautiful, a girl like a countryside;

and I know how to give forgotten compliments, and you move on;

and you think that one needs to watch what is needed,

and I think about shivering animals that will once again

piss close to the air like they used to; and you

make me a musical list of clothes to dry

in the generous and hapless air of our camporella.

Villa’s poems — complicated, confounding, exciting, rewarding — are a seed among eyes.

–Stephan Delbos

https://bodyliterature.com/2016/04/08/the-selected-poetry-of-emilio-villa-friday-pick/

Poetry is notoriously difficult, some say impossible, to translate. But what does it matter, really? If a reader finds a German Dante, an Arabic Wallace Stevens, or a Quixote in Tagalog that speaks to her, moves him, enlightens us, then why not embrace it? And if a publisher gives us a bilingual edition, all the better. It cannot distract anyone too much nowadays and may well allow a deeper understanding of the original to see how another reader has interpreted it in a second language. Moreover, the bilingual Italian/English Selected Poetry of Emilio Villa (1914-2003) translated by Dominic Siracusa (New York, Contra Mundum Press, 2014) has the considerable additional merit of introducing an under-appreciated twentieth-century Italian master to the Anglophone public. Bilingual in this case is only a manner of speaking, since Villa’s originals are also in idiosyncratic classical Greek, Latin, French, English, Portuguese, Provençal, and Milanese with a free-handed sprinkling of words in other languages.

Admittedly, there is a long tradition of disparaging or at least claiming ambivalence about bilingual editions. Aldus Manutius at the turn of the sixteenth century performed typographic contortions to create parallel Greek/Latin editions that could be read on facing pages but also sold as separates (or separated after the fact), apparently because he felt his substantial audience of native Greek readers would find a Latin crib insulting. But Aldus’s noblest goal was to transmit Greek learning to a new, Western European public, even to translate an entire ancient civilization for his own modern age. It is an ideal we need more than ever in our own, all too centrifugal age. Certainly, Emilio Villa, a vatic poet if ever there was one in the twentieth century, deserves an English translation for the twenty-first. Dominic Siracusa and his collaborators have given us a fine and useful one.

The model of Aldus is particularly appropriate to cite in the present case, since Villa’s always-experimental poems often depended in part on a particular sort of typesetting. It was necessary for Siracusa, publisher Rainer Hanshe, and designer Alessandro Segalini to translate the graphics as well as the words (see Segalini’s “Options” Imposed). Siracusa opines in his introduction to this substantial, seven-hundred-page anthology that Villa was not interested in typographic experiments for aesthetic reasons after the manner of the Futurists or shaped-poetry avant-gardists like Apollinaire. Villa, that is, was not looking for striking visual effects. Siracusa tells us (and the poems in this volume confirm) that Villa’s eccentric typography was intended to emphasize “the indeterminate nature of language.” He adds, “One could say that the blank spaces that perforate Villa’s pages are almost a reaction to and not a continuation of the experiments [of earlier poetic radicals].” This attitude toward language, this impulse to destabilize, is a constant in Villa’s poetry and informed his art criticism. He indulges in word-play incessantly but even at his most playful he is dead serious about disrupting our usual sense of how language works.

It is clear that this attitude toward language derived from Villa’s study of ancient languages, particularly the pre-Hellenic and pre-Hebraic languages of the Mediterranean and Middle East. We might even see in this another echo of the Aldine project, at least to the degree that it looked to the ancient world for wisdom embodied in little-known languages. Here again, Siracusa’s introduction is a valuable guide, emphasizing as it does Villa’s life-long project to translate the Old Testament in a manner that would strip away all the theological interpretations that assigned narrowly specific meanings to the ancient texts and return them to some semblance of their original force as open-ended, multivalent, mythic narratives. One of the advantages of the present anthology is that it includes a short passage from Villa’s translation of Genesis, a retelling of the Fall that goes a long way toward explaining why language was the creative force for Villa. For Villa both gods and men — and indeed the rest of the universe — were created by language, what he himself called the Verbum naturans or Verbum operante. His account of the Fall has everything to do with the power of language to create knowledge and morality and to disrupt them.

Once we leave behind Siracusa’s excellent, succinct introduction, which is complemented by a useful bibliography, we set sail upon the choppy seas of Villa’s poetry. It is an exciting, rewarding voyage but not always easy going. The Selected Poetry is presented with minimal apparatus in roughly chronological order following dates of publication. In this Siracusa departs from the practice of earlier Italian collected editions and from that of the excellent critical edition of Villa’s Opera poetica that appeared in the same year (Rome, L’Orma, 2014) edited by Cecilia Bello Minciacchi, which used a chronology based primarily on presumed dates of composition. Villa often worked on a given piece for decades before publishing it or simply left things unpublished. Composition dates are hard to determine; Villa often included or added them in his manuscripts, but mostly retrospectively and in many cases after the stroke that debilitated him in 1986, so they are often just guesses. Then too, several important collections of verse were published after his stroke, when he was no longer writing new poems and while his literary affairs were supervised by Aldo Tagliaferri. Siracusa has included a generous selection of these, and he returned to manuscript copies for some texts. He also included two pieces hitherto unpublished, for which he relied on manuscripts; wisely, he does not hazard a date for either.

There are wonders here on almost every page. The early poetry is easier to approach — it is a calmer sea than later work, though deceptively so since the waters definitely run deep. Villa’s love for incantatory diction was evident from the very start. Siracusa gives us several poems from a collection, Adolescenza: Liriche, that was published when Villa was barely twenty years old. These poems are not great; in fact, Bello Minciacchi relegates them to an appendix as examples of Villa’s precocious but derivative “compositional technique.” Even the title of the collection suggests some (at least false) modesty on young Villa’s part. Still, in the very first poem on offer in English, Villa addresses “My Poetry” as “Virgin air created,” and “Virgin breath.” Almost every poem thereafter partakes of this kind of insubstantiality — airy or liquid or aflame. At the risk of overdoing my analogy to an excursion on the ocean, it is as if the reader sets out on the waters with a net that never captures the sea-substance itself but only the creatures, living and lovely or grotesque, that float close enough to the surface to be brought up into sight. We can only imagine what lies around or below.

But honestly, I should leave my own poor similes aside. Siracusa at one point compares himself to Melville’s Ahab, but Villa provides plenty of better images that apply directly to his poetic labors. You do not even have to go far to find him in a piscatorial mood:

fish the moon in the ditch with the rake

quick wise eager hand, and what a moon! that

of the great popular nights and the grey

fog in the unique heart of the bat,

of the lovers in public gardens,

or maybe the big moon of the well of cats of ditches?

or that of the stokers and engineers

of tides? or that of the evening

in the glass of grappa and at roof level?

-from no. 13 of the “17 Variations on Themes Proposed for a Pure Phonetic Ideology,” 1955

In such a world, created by a grammatical anarchist like Villa, every poem repays multiple readings.

Villa’s first great poems appeared in Oramai (“By Now,” 1947) which is richly excerpted here. These are still early, straightforward pieces, but Villa has found his voice and it is already a powerful one. Many of these poems reflect the darkness of the late Fascist period and a few are obviously political enough that they could not have been published before the end of the war, parts of which Villa spent in hiding. One of the most impressive takes its title from the Latin version of Job 14:1, “Man that is born of woman is of few days.” Siracusa leaves the title in Latin (Natus de muliere, breve vivens), but follows Villa directly to the point, which has as much to do with Genesis as Job: “Without a doubt man in nature / was invented like a point-blank scream: hate, / wrath, garments…” And this poem’s conclusion has everything to do with the suffering of Italy during the war: “…the soul / escapes, reckless, vile, / strong taken by national / pleasure: and maybe it’s that / just maybe here we need a change of scenery, / everybody: it’s a suggestion, / a conclusive argument.” This is a particularly nice bit of translation, for the start-and-stop rhythm of the English does full justice to that of the original. - Paul F. Gehl

Read more here: https://thedecadentreview.com/corpus/emilio-villa-in-english/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.