Frédéric Forte, Minute-Operas. Trans. by Daniel Levin Becker, Ian Monk, Michelle Noteboom, and Jean-Jacques Poucel. Burning Deck, 2015.

Frédéric Forte’s Minute-Operas are poems “staged” on the page. A simple vertical line of 3 inches separates what Forte calls the stage and the wings. The poet explores the potential of this form with multiple typographic games, calling on different registers of the language, different poetic techniques and, in the second part of the book, by “fixating as minute-operas” 55 existing poetic forms (come out of various poetic traditions or more recently invented by Oulipo, the famous French “Workshop for potential literature.”)

The poems of Minute-Operas also constitute, in their cryptic way, a journal of the poet’s life during the period of composition (2001-2002): his love life, the loss of his father…

It was shortly after the publication of this book, in 2005, that Frédéric Forte was elected a member of the Oulipo.

“A book as intriguing (by its staging of typographic variations) as it is invigorating (in its micro-narratives).”

—Emmanuel Laugier, Le Matricule des Anges n°67 (octobre 2005)

—Emmanuel Laugier, Le Matricule des Anges n°67 (octobre 2005)

“Extraordinary inventiveness…funny, original, brilliant”

—Jean-Michel Espitallier, Caisse à Outils: Un panorama de la poésie française aujourd’hui (Pocket, 2006)

—Jean-Michel Espitallier, Caisse à Outils: Un panorama de la poésie française aujourd’hui (Pocket, 2006)

Frédéric Forte was born in Toulouse, France, in 1973, and is a member opf the Oulipo since 2005. The most recent of his seventeen poetry collections are Une collecte (Théâtre Typographique, 2009), Re- (Nous, 2012) and 33 sonnets plats (Éditions de l'Attente, 2012).

He has translated into French the American poet Michelle Noteboom and, with Bénédicte Vilgrain, the German poet and Oulipian Oskar Pastior. He lives in Paris, where (among other things) he runs the blog poète-public.

In English: Seven String Quartets has appeared from La Presse fall 2014.

As the title of Frédéric Forte's collection (can) suggest, the 'minute-operas' presented here are small and short, the minute applicable both to their (limited) temporal as well as spatial dimensions. They are 'operas' (also) in the traditional-original sense of the word: simply 'works' -- yet even as these texts are not set to music they are more than merely words (though also not libretti, in the familiar form). The stage for these performance-pieces remains the page -- but, through a creative use of typography and presentation, Forte shows how much one can achieve in two dimensions.

Forte is a member of the Oulipo -- the 'workshop of potential literature' -- so the word- and structure- (and strictures-)play in everything from the title onwards comes as no surprise. This volume is presented in two parts -- 'phases', he calls them -- , the first simply (if one can put it that way ...) 'minute-operas', the second applying a wide variety of (mainly) Oulipian forms to the individual pieces (with a 'detailed index' offering a summary definition of each particular applied form).

Practically each 'minute-opera' has a three-inch vertical line as a major element, separating elements of the text -- what's on 'stage' and what's in the 'wings', Forte suggests, but the reduction and separation is rarely quite that simple. What's to the left of the line, usually in smaller print, isn't merely marginalia or stage-directions; what's to the right hardly just the action, so to speak. Complicating matters, the line is not always simply a complete barrier: there are pieces where the text runs over it as if it weren't there, while elsewhere the line isn't straight. Among the most visually beautiful is a poem in which there is not just the familiar line on the left side of the page, but four, at ninety-degree angles, forming a box, in the top left outside corner the text: "use / the void"; in the bottom right outside corner: "the void / used". Another presents the 'skeleton' of an onzina (a 'level-11 quenina, an eleven-by-eleven poem represented (except for some words in the wings) entirely graphically/visually.

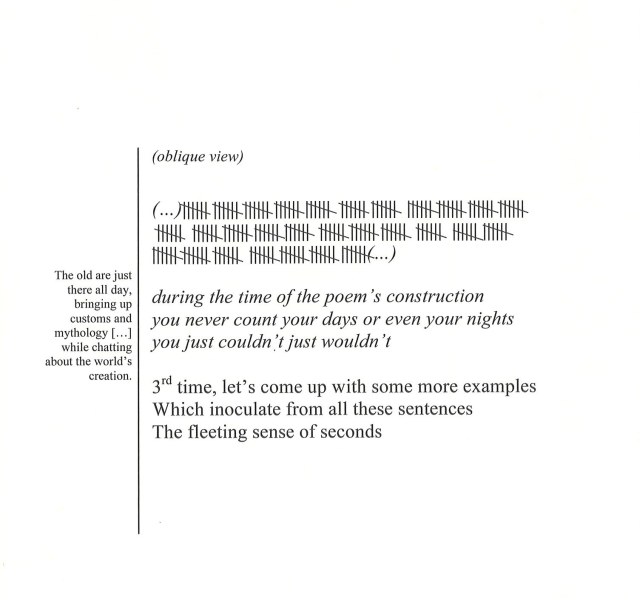

It's almost pointless to present an example because, as with so much Oulipo work, a great deal of the point is the variations on the theme, but this (in the French original, and a rare one with hand-drawn elements) is as good an example as any:

An index defines and explains (more or less) the different 'fixed forms' Forte uses in each of the phase-two pieces, an entry typically reading:

Heterogram, 103. Invented by Georges Perec. The letters chosen by the poet (the ten most frequently used in the French alphabet, plus one) cannot be used again before the whole series is completed.

Some are much more simple/obvious:

French sonnet, 101. Where to begin ?

And even this space is used for occasional commentary:

Haiku, 71. Needs no introduction. Unlike the chant royal the minute-opera is a bit baggy for it.

Forte's remarkable variations -- 55 of them -- range from some of these traditional poetic forms (though even the haiku becomes something quite extraordinary in its visual presentation) through all sorts of Oulipian games. There's even a traditional Algol poem -- following Noël Arnaud's 1968 Poèmes Algol, "using only the limited vocabulary of the computer language Algol".

Minute-Operas is a beautiful, fascinating, puzzling collection. These are very much visual texts: the words count and matter (and, indeed, there's a lot not so much hidden but tied into them, in Forte's use of Oulipian forms and constraints), but the greater rewards are in the creative interplay between (graphic) form and content. The texts, certainly, aren't for the most part immediately very approachable, but the presentation makes them all at least intriguing -- and draws the reader in, to figure out what's going on here.

Arguably, Minute-Operas functions much like (musical) opera, in that it can appeal even to the uninitiated on a surface level, even as it frustrates in its less accessible deeper elements. The sheer spectacle, however, impresses enough at least to warrant that first look -- many of the pages are practically wall-ready works of art, and the book can be enjoyed entirely on a visual level, almost ignoring the text -- while there's so much behind it that the effort of second (and further) looks and closer readings is well-rewarded, too. - M.A.Orthofer

First up from the American Literary Translators Association, 2016 National Translation Awards longlist for Poetry (geez that’s a mouthful), is Minute-Operas by Frédéric Forte (Translated from the French by Daniel Levin Becker, Ian Monk, Michelle Noteboom & Jean-Jacques Poucel).

Stepping into Frédéric Forte’s work is like stepping into a vast sparse gallery space, open space around you, take time to ponder what your eye has been drawn towards. Broken into two sections, “Phase one – January – October 2001” and “Phase two – February – December 2002”. Each section containing 55 “poems” or creations.

Each poem is “Staged” on the page, where a “simple vertical line of 3 inches (I measured the line thinking it would more likely to be in centimetres, but inches it was, I wonder if this is part of the translation or a US audience too?) separates, what Forte calls the stage and the wings”. Typographically the word creations then perform on this stage created on each page. It is probably best to cite an example.

This example showing the passing of time, the polar opposites of marking off weeks but stating that during a “poem’s construction you never count your days”, ageing and creation (in the wings) whilst the seconds pass on the stage. Complexity all on a single page. To quote the ‘Preface” from “The End of Oulipo? An attempt to exhaust a movement” by Lauren Elkin and Scott Esosito;

The concept of potential literature is founded on a paradoxical principle: that through the use of a formal constraint the writer’s creative energy is liberated. The work which results may be “complete” in itself, but it will gesture at all the other work that could potentially be generated using that constraint.

The poem I have used as an example doesn’t actually fall into the Oulipian section of Frédéric Forte’s work, which in fact comes in phase two, but the concept of the paradox and liberation are stunningly obvious.

This is a collection that forces you to pause, as if in an art gallery, to observe, linger, absorb, reflect before moving on, each poem an artwork in its own right, a creation that can work on numerous levels, artistically, literary, poetically, theatrically or even structurally.

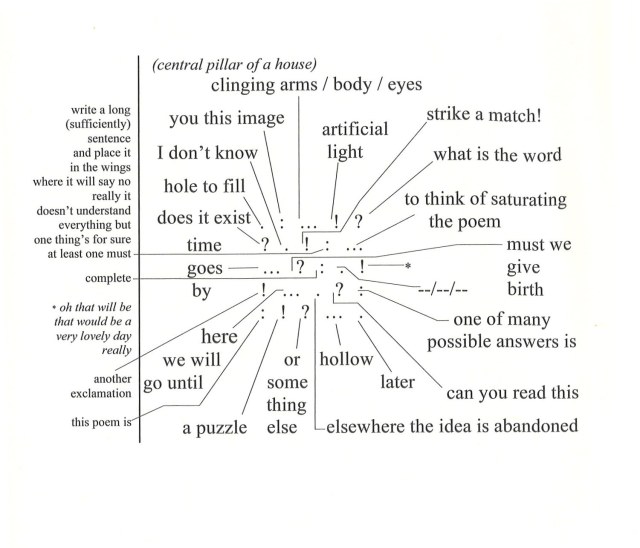

Phase two’s poems come with a “Detailed index of fixed forms” where the poem uses existing poetic forms, either traditional or invented by the Oulipo. Another example for you;

Here the detailed index explains that the poem is a “Quintina. Level-5 quenina. In (central pillar of a house [the title of the poem]) the permutation operates on punctuation marks.” Permutations boundless in this example, I‘ll leave it for you to ponder.

This book is not only a feat of typographical wonder, to even contemplate the translation that would have been required, is a feat in itself. For example, the oulipo ‘heterogram’ “invented by Georges Perec. The letters chosen by the poet (the ten most frequently used in the French alphabet, plus one) cannot be used again before the whole series is completed. In the poem ‘(whistle statue II)’ the letters “SILENTBAROU” go through various iterations as words (eg. Silent Bar: our tale is….) eleven times until they end with the words “burial stone”. How on earth did this originally appear in French and how did the translator make it coherent in English? I’m still astounded, initially upon reading the poem, again when taking my notes, and now when attempting to explain it.

The cover of the book tells us that the content of the poems “also constitute, in their cryptic way, a journal of the poet’s life during the period of composition (2001-2002): his love life, the loss of his father…” unfortunately this depth was something that was personally lost in the translation. Whilst the word games, and cryptic style was extremely impressive, the content, as a cohesive whole, seemed to fall by the wayside.

Phase two of the book containing fifty-five word games for you to explore slowly, wonder upon, stretch your limits, refer to the index and back to the poem, research, ponder. An absolute marvel of potential literature. The first fifty-five poems more structured within the space confines, created by the poet, or simply the limits of the page, but still wonderfully rich and detailed in their construction.

A collection that I think would not be out of place in an art gallery. Illuminating and one I will revisit often, if simply just to be stunned at the creation involved.

In a nut shell this is a book I can’t adequately review, here’s what others have said….if that helps…

“A book as intriguing (by its staging of typographic variations) as it is invigorating (in its micro-narratives).” —Emmanuel Laugier, Le Matricule des Anges n°67 (octobre 2005)

“Extraordinary inventiveness…funny, original, brilliant” —Jean-Michel Espitallier, Caisse à Outils: Un panorama de la poésie française aujourd’hui (Pocket, 2006)

“positively acrobatic, even balletic” – ALTA Blog

How about you buy a copy and see for yourself? I can guarantee literary lovers, Oulipo readers and poetry aficionados will not be disappointed. - messybooker.wordpress.com/2016/09/02/minute-operas-frederic-forte-translated-by-daniel-levin-becker-ian-monk-michelle-noteboom-jean-jacques-poucel/

“Quand le temps décide répète” – an interview with Frédéric Forte by SJ Fowler.

It is rather apt, or rather remiss, that for the fiftieth edition of Maintenant we present our first French poet. The first of many no doubt. It is all the more appropriate, given our dictum, that our first French subject is the youngest, and 35th, member of Oulipo. As the most contemporary representative of that legendary group of writers and poets, it goes without saying Frédéric Forte is an adroit, inventive and certain presence in the ever-lively and rich French poetry scene. We are extremely pleased to mark our half-century featuring a poet who epitomises our commitment to urbane, intelligent and important poetry which is still evolving into its own distinguished completion.

3:AM: Let us begin with a discussion of your involvement with Oulipo. How did you become to be a member of the group?

Frédéric Forte: I discovered modern poetry by reading Raymond Queneau (I was around 24 y.o.). I had heard of Oulipo before but this renewed my interest for it: I read Roubaud, etc. (and also a lot of non-Oulipian contemporary poetry).

When I decided 2 years later to ‘seriously’ become a poet, I began naturally to work on more largely formalist texts. I felt this was my way to be a writer. The Oulipo represented an intellectual family of people thinking the same way as I was. So after that, I sent my works to Oulipian poets like Jacques Roubaud, Jacques Jouet and Michelle Grangaud. That’s how the Oulipo became aware of my existence. In 2002, I was invited to a monthly reunion. There, I met the English and Oulipian poet Ian Monk and we wrote together a bilingual book named N/S. And in 2005, after I published Opéras-minute, the group decided to cooptate me as its 35th member.

3:AM: Could you detail the content of your work with Ian Monk?

FF: N/S is a book made of 8-lines bilingual poems (4 lines in French, 4 in English). The idea was to cross formally both languages in all the ways possible. For an 8-lines poem, there are 70 combinations — from EEEEFFFF to the contrary (FFFFEEEE) going by FEFEFEFE for example (E is for English and F for French of course). There’s no rhyme or fixed meters involved in the process.

The title means “North / South” or “Nord / Sud” because Ian Monk lives in Lille (north of France) and I was living at the time in my hometown, Toulouse (in the South-West).

Ian and I sent 4 lines, at a time, to each other by e-mail in order to complete the poem. Once we completed the first 70 poems, we did it again in “reverse mode” and then Ian translated the whole work in mirror. Finally the book contains 280 poems (140 originals and their translations).

3:AM: Has Jacques Roubaud proved a significant influence upon you as you have come to know him?

FF: As I said I first discovered Roubaud’s work when I was looking for Oulipian books, after the ‘Queneau trigger’. And it completely turned upside down my conception of poetry. I found out that a poem could be at the same time abstact and lyrical, intimate and formal, playful and deep, a very unique kind of conceptual object. After the first shocks that have been ” ” (which means actually ‘belongs to’ in maths) or “Quelque chose noir” I read everything of his and nothing made me change my mind on the importance of his work. I think Roubaud is the only ‘genius’ that I ever met and also a very kind man, discrete, respectful and not trying to impose his views to the others. He is a master I freely chose but absolutely not a guru!

3:AM: What methodologies do you pursue in your work that might be recognisable to those who are familiar with Oulipo through the work of Perec, Roubaud, Mathews etc…?

FF: Each Oulipian has his own approach of writing and his own methodologies. For my part, I mostly dedicate my efforts to use fixed forms and invent some new ones… In a way, it’s a ‘tradition’ in the Oulipo history…

3:AM: What are some of the new forms you have invented in writing your poetry?

FF: I haven’t invented very many actually… Let’s say: the ‘opéras-minute’ (a kind of spatial meta-fixed form that may fix other forms!), the book should be translated soon and published (if everything goes well) by Burning Deck in 2 or 3 years… ; recently I began to write long prose poems called ’99 preparatory notes to…’ where I try to ‘think’ (poetically) about something (the blue of the sky, the impossible or the action of slowing down, for example). This form is very useful when a review asks you for a text: “What is the subject? Aquatic life? Ok, I’m gonna write ’99 preparatory note to the aquatic life!”

Most of the time I work on older forms (sonnet, sestina, etc…) and I try and find a way to renew them…

3:AM: While many philosophically justified movements in poetry seem to have their day and then die away (the nouveau roman an example, an interesting discussion in itself and its relationship to Oulipo), aping the ‘seasonal’ nature of philosophy, it seems the Oulipo movement, in poets like yourself, is renewed, renewable even and still a vital presence in French poetry. Do you think this is true? If so, why?

FF: I would say first that the Oulipo is not a ‘movement’, it’s a group of people, not trying to persuade they’re good and the others are bad, but just working, generations after generations, on the potentialities of literature. This maybe could plainly explain the longevity of the group.

I don’t know if the Oulipo is ‘vital’ for French poetry, maybe it would be pretentious for me, as an Oulipian, to say it. All I know is: it’s alive and it’s part of the thing. The Oulipian logic brings poetry in new, different directions (as others approaches do in their own ways). The important point is to keep poetry as diverse and alive as possible.

3:AM: You have translated English texts into French, do you engage in a lot of translation work?

FF: Not really. I’ve done (along with the poet Bénédicte Vilgrain) an ‘Oulipian’ translation from the German of Oskar Pastior’s anagram-poems. I have also translated Uncaged, prose poems by Michelle Noteboom (who is an American poet, and my partner). To have the author at home helped me a lot! And I will do it again soon, I hope. But, really, I consider the translation of poetry as a poetic act itself. To translate a text is a wonderful way to deeply know it and it’s also a way to explore new territories for your own poetry.

3:AM: You worked as a bookseller, do you consider this your profession? Does it support your poetry?

FF: I love bookshops, I’ve got a lot of friends working as booksellers but this is not my profession. It used to be a job. And in a way, a difficult job for a poet who could see every day that a lot of readers are not curious about poetry at all.

For now, I have the incredible chance, to earn money doing what I love. Not with the book sales of course but doing residencies, public readings and workshops. It’s a luxury. And I don’t know how long it will last.

3:AM: Do you think France as a nation is producing the talent in poetry to match it’s immense poetic history?

FF: Yes! Not because of me of course. But I think the poetry production is vivid, with a lot of authors exploring language in many directions, and great (small) presses to publish them.

3:AM: Are there defined movements and styles in poetry emerging from the next generation of poets? Are there young poets coming to the fore whom you admire?

FF: I don’t really see ‘defined movements’ emerging at this time. But maybe I don’t clearly see. They are many ‘styles’, many directions, as I said, explored by French poets. Too many to detail them here. There’s an excellent book about it if you’re interested by the subject : Caisse à outils by Jean-Michel Espitallier (“a panorama of today’s french poetry”).

I like a lot of ‘young’ (or less young) poets. A few names : Eric Suchère, Anne Parian, Marie-Louise Chapelle, Sébastien Smirou, Cécile Mainardi…

3:AM: Is there a difference in the culture of poetry (it’s nature, the attention it’s given etc…) between those writing in Paris and elsewhere in France? Does each city, and each individual region produce definitively different work, while generalising of course?

FF: You know that France is a ‘jacobin’ country, very centralized. I would say Paris attracts a lot of artists, like a magnet. I was born in Toulouse and if I decided to move in Paris quite recently it’s of course because of my Oulipo membership but also because so many things occur in Paris that don’t exist elsewhere in France. Nevertheless, many great poets live in other French cities. And, for the poetry I like, I don’t see clear distinctions between Parisian and non-Parisian poets.

It’s true, another kind of ‘regional’ poetry also exists, I would say, in a very reductive way, ‘countryside poetry’. But I’m not really aware of it… and not interested in (shame on me).

Photo copyright : © Hermance Triay

Frédéric Forte, Seven String Quartets. La Presse, 2014.

Frédéric Forte's fleeting poems borrow the structure and arrangement of the string quartet, but rather than performing in concert, these poems keep tuning their instruments, fidgeting and fussing, sighing and shrugging, until they quietly exit the stage. Throughout, one is swept along by what turns out to be a surprisingly subtle, finely nuanced performance.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.