Nick Sousanis, Unflattening, Harvard University Press, 2015.

spinweaveandcut.com/The primacy of words over images has deep roots in Western culture. But what if the two are inextricably linked, equal partners in meaning-making? Written and drawn entirely as comics, Unflattening is an experiment in visual thinking. Nick Sousanis defies conventional forms of scholarly discourse to offer readers both a stunning work of graphic art and a serious inquiry into the ways humans construct knowledge.

Unflattening

is an insurrection against the fixed viewpoint. Weaving together

diverse ways of seeing drawn from science, philosophy, art, literature,

and mythology, it uses the

collage-like capacity of comics to show that perception is always an

active process of incorporating and reevaluating different vantage

points. While its vibrant, constantly morphing images occasionally serve

as illustrations of text, they more often connect in nonlinear fashion

to other visual references throughout the book. They become allusions,

allegories, and motifs, pitting realism against abstraction and making

us aware that more meets the eye than is presented on the page.

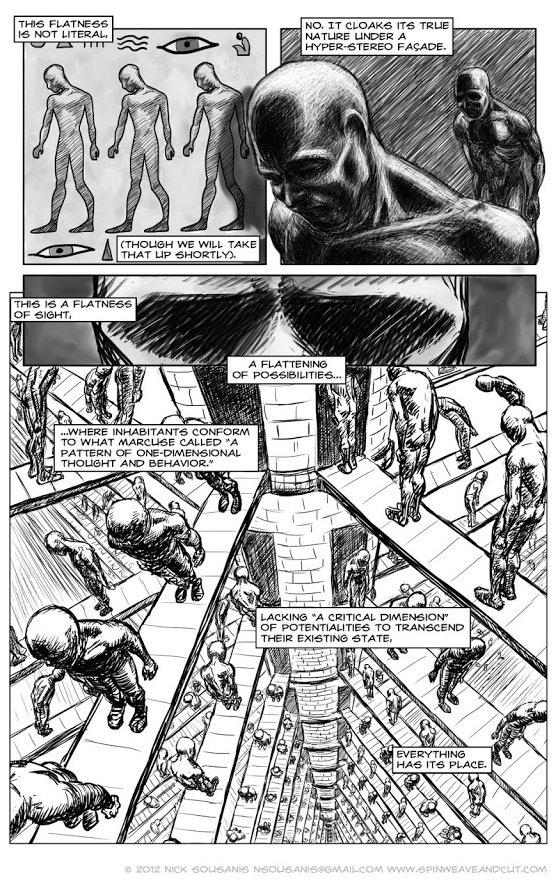

In its graphic innovations and restless shape-shifting, Unflattening is meant to counteract the type of narrow, rigid thinking that Sousanis calls “flatness.” Just as the two-dimensional inhabitants of Edwin A. Abbott’s novella Flatland could not fathom the concept of “upwards,” Sousanis says, we are often unable to see past the boundaries of our current frame of mind. Fusing words and images to produce new forms of knowledge, Unflattening teaches us how to access modes of understanding beyond what we normally apprehend.

Listen to Nick Sousanis discuss Unflattening on the Publishers Weekly podcast More to Come

If Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics charmingly investigated the history, development, and formal features of visual narrative, Unflattening is its equally brilliant epistemological counterpart. With profound depth and insight, Sousanis looks at how the ‘unflattening’ possibilities of this form of storytelling allow us to see the world from entirely new perspectives… Written with remarkable clarity and insight, its sometimes-haunting, sometimes-breathtaking illustrations prove the book’s arguments about how visual information can shape our understanding… Weaving together language, perception, and the theory of knowledge in an investigation of how the multidimensional possibilities of graphic storytelling can awaken us to ways of knowing from multiple perspectives, Sousanis has made a profound contribution to the field of comics studies and to semiotics, epistemology, and the burgeoning study of visible thinking. Essential reading for anyone seeking to create, critique, or consider the visual narrative form. - Publishers Weekly

An important book, Unflattening is consistently innovative, using abstraction alongside realism, using framing and the (dis)organization of the page to represent different modes of thought. The words and images speak for themselves and succeed on their own terms. I couldn’t stop reading it. - Henry Jenkins

Sousanis’ main argument is that images, in conjunction with text, can help us understand the world around us in ways that are impossible for text to do on its own. Indeed, the format he’s chosen itself works to support the thesis. For Sousanis, it’s all about new perspectives. He uses a visual analogy of eyes working together to produce a stereoscopic view of our environment to demonstrate. Because of the space between them, each eye sees the world from a unique perspective, but only when used together are we able to perceive depth. It takes two different views operating in tandem to come to a new understanding about what’s being observed. And that’s just the beginning of the rabbit hole.

The second thing that strikes me is that, despite this not being a narrative, I can’t help but apply narratives to Sousanis’ stunning images. The book opens with illustrations of human figures moving along a complex system conveyor belts. It’s the assembly line from hell (maybe the DMV?), with signs hung reading “Stay in Line” and “Maintain Proper Distance”. Each figure stands uniformly submissive, with their heads and shoulders slumped. They look sad, and I immediately begin to wonder about them. Who are they? How did they get here? It’s a dramatic image. And the more I think about, the more in awe I am of what Sousanis has accomplished here. I’ve never read a scholarly work that elicited this kind of emotional response from me. To be clear, this is a truly intellectual volume, one which earned its author a PhD in education, but it’s also a very stirring work of art. How many PhDs can say that about their dissertations?

This emotional component adds another dimension to the reading, while simultaneously contributing to his argument. According to Sousanis, part of the reason the world became “flat” is that we’ve lost some of our sense of wonder. Our accumulation of knowledge has accelerated exponentially, leading to increasingly narrow fields of study as we strive to draw in all the edges of the map. We’ve answered most of the big questions, the ones that first stirred us to wonder. Now as we look further out, or more deeply in, we compartmentalize, closing ourselves off from other perspectives. Sousanis is suggesting that a more interdisciplinary discourse is needed in order to come to new understandings about, well, everything. It’s a call to action, that action being to wonder. Ah, but there’s, as Shakespeare wrote, the rub – wonder is both an action and a feeling, speculation and awe. Which is he asking of us? The text points us in one direction, the images move us in another, and the answer appears to be in a magical third space in between.

This is a fascinating achievement. I’m a firm believer in comics’ ability to illuminate the dark corners of the world, to inspire growth and change, the way that all great literature does. But I never imagine comic books functioning as anything other than a storytelling medium. I never consider their capacity to communicate in other ways. What are the limits of its applications? How much longer before we begin seeing the first textbooks in comic book form? Comic book souffle recipes? Legal contracts? Tax forms? I suppose the answer to that lies in our willingness to de-compartmentalize, and step away from our narrow – sometimes strongly-held – views, in order to gain a new perspective. - Joseph Manuel Nieves

Inside Higher Ed Interview: Seeing in New Dimensions

760 WJR Detroit radio, The Relevant University “The Trend of Visual Literacy”

The Chronicle of Higher Education “Amazing Adventures of the Comic Book Dissertator”

review at MIT Center for Civic Media

In its graphic innovations and restless shape-shifting, Unflattening is meant to counteract the type of narrow, rigid thinking that Sousanis calls “flatness.” Just as the two-dimensional inhabitants of Edwin A. Abbott’s novella Flatland could not fathom the concept of “upwards,” Sousanis says, we are often unable to see past the boundaries of our current frame of mind. Fusing words and images to produce new forms of knowledge, Unflattening teaches us how to access modes of understanding beyond what we normally apprehend.

Listen to Nick Sousanis discuss Unflattening on the Publishers Weekly podcast More to Come

If Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics charmingly investigated the history, development, and formal features of visual narrative, Unflattening is its equally brilliant epistemological counterpart. With profound depth and insight, Sousanis looks at how the ‘unflattening’ possibilities of this form of storytelling allow us to see the world from entirely new perspectives… Written with remarkable clarity and insight, its sometimes-haunting, sometimes-breathtaking illustrations prove the book’s arguments about how visual information can shape our understanding… Weaving together language, perception, and the theory of knowledge in an investigation of how the multidimensional possibilities of graphic storytelling can awaken us to ways of knowing from multiple perspectives, Sousanis has made a profound contribution to the field of comics studies and to semiotics, epistemology, and the burgeoning study of visible thinking. Essential reading for anyone seeking to create, critique, or consider the visual narrative form. - Publishers Weekly

An important book, Unflattening is consistently innovative, using abstraction alongside realism, using framing and the (dis)organization of the page to represent different modes of thought. The words and images speak for themselves and succeed on their own terms. I couldn’t stop reading it. - Henry Jenkins

For Nick Sousanis, editing his dissertation will be much messier than

pressing the delete key and retyping passages.

That's because Mr. Sousanis, with the blessing of his advisers, is writing and drawing his dissertation about comics in comic-book form. He believes his dissertation, in interdisciplinary studies at Columbia University's Teachers College, is the first of its kind.

Mr. Sousanis grew up reading comics—he says his first word was "Batman"—and he drew them in high school. But his dissertation doesn't involve the usual superheroes who fight villains bent on world domination. Ever since Superman's first appearance in 1938, Mr. Sousanis says, people have associated comics with a limited range of genres. But they're increasingly being created and used in the classroom to help students retain information, so last fall he taught a course about teaching and learning with comics.

His dissertation, "Unflattening: A Visual-Verbal Inquiry Into Learning in Many Dimensions," expands on that subject. It explores how comics' interwoven elements open up new avenues for creating and learning that aren't possible through writing alone. Mr. Sousanis calls the work a series of "philosophical essays" that employ images and metaphors. He uses a text outline as a scaffold to flesh out sketches on large sheets of paper, and finishes the final drawings on a computer.

He hopes the results will be richer than the typical double-spaced, 12-point font format.

"I know if I took a research paper I wrote of the same topic, the same density, there's no chance I could hand it to somebody on the street" and they would read it, he says. "My mom might read it, but that's about where it would end." - Nick DeSantis

That's because Mr. Sousanis, with the blessing of his advisers, is writing and drawing his dissertation about comics in comic-book form. He believes his dissertation, in interdisciplinary studies at Columbia University's Teachers College, is the first of its kind.

Mr. Sousanis grew up reading comics—he says his first word was "Batman"—and he drew them in high school. But his dissertation doesn't involve the usual superheroes who fight villains bent on world domination. Ever since Superman's first appearance in 1938, Mr. Sousanis says, people have associated comics with a limited range of genres. But they're increasingly being created and used in the classroom to help students retain information, so last fall he taught a course about teaching and learning with comics.

His dissertation, "Unflattening: A Visual-Verbal Inquiry Into Learning in Many Dimensions," expands on that subject. It explores how comics' interwoven elements open up new avenues for creating and learning that aren't possible through writing alone. Mr. Sousanis calls the work a series of "philosophical essays" that employ images and metaphors. He uses a text outline as a scaffold to flesh out sketches on large sheets of paper, and finishes the final drawings on a computer.

He hopes the results will be richer than the typical double-spaced, 12-point font format.

"I know if I took a research paper I wrote of the same topic, the same density, there's no chance I could hand it to somebody on the street" and they would read it, he says. "My mom might read it, but that's about where it would end." - Nick DeSantis

“In the beginning was the Word.” But what do we lose when we value language

over images? And how can we think using both at once, the visual and the

verbal?

Artist and educator Nick Sousanis made waves in academic circles last year by presenting his doctoral thesis at Columbia University in the form of a comic book, now released as Unflattening. The medium was vital to Sousanis’s message: a comic which dethrones the primacy of words over pictures in Western thought, and posits comics as an art form which transcends both.

This isn’t Magritte’s “Treachery of Images,” taunting us with “Ceci n’est pas une pipe" (1929). Sousanis is keen to explain; he’s more teacher than provocateur. He describes comics as a way of juxtaposing the visual and verbal in meaningful order. This medium, he argues, helps us to see all things—concepts, objects, abstractions, fantasies, experiences—in relation to one another. Although the implications are profound, Unflattening is less an insurrection than a carefully argued case for rethinking our priorities about art and learning.

Unflattening is above all a humane piece of scholarship which challenges our assumptions about perception. Sousanis reminds us that all art and knowledge are created by beings who inhabit bodies and see the world from a unique perspective, and that every mark on a page or painting was authored by some living hand.

Sousanis works with a wide range of visual and verbal references, drawing imagery from TV and movies, natural science textbooks, and the classical canon of art. In the opening page alone he acknowledges the inspiration of Piranesi’s etchings, set design from the Batman films, and Star Trek: The Next Generation. But this book is neither a geek-fest nor a referential ramble.

With its breadth and ambition, Unflattening doesn’t aim to deeply interrogate every last one of the texts it calls on. Its tone is oracular, and Sousanis’s attempt to leap beyond the limit of mere words leads him, by necessity, away from close textual analysis. Allusions to Bruno Latour and Herbert Marcuse flit past in the kaleidoscope of words and images. An aphorism from Kahlil Gibran bears as much weight here as Deleuze and Guattari. Sousanis compares the process of exploring ideas to that of measuring a coastline: as the length of our measuring unit decreases, we find ever more tiny and subtle folds in the shore. An ant that walks the exact border between sea and land must weave a longer path than a heavy-footed human. Sousanis’s book seeks to outline a vast conceptual geography, and its map can only sketch out some finer points in the territory he surveys. Still, these limitations only challenge us to take Unflattening’s method further. Reading the book, one tries to imagine finely treading the shoreline between the visual and verbal, as an ant would. With Sousanis’s large-scale map in hand, we can seek a way of interrogating both words and images ever more meticulously.

Unflattening’s very first image, on the dedication page, is the double footprint of Sousanis’s daughter, born while he was writing his doctoral thesis. As readers, the author invites us to take our first steps, too: to recognize the many different ways humans have of perceiving, and see the world anew. This is the work of an expectant father, seeking not to limit the future or deny the past, but to unlock doors and invite others to discover their potential. - Matt Finch

In case you haven't noticed by now, this is a very unique book. I was told that Unflattening is the "first doctoral dissertation written and drawn entirely in comic book form," but that's misleading. This isn't a comic book. Nick Sousanis has done something rather incredible: he has taken philosophical concepts, scientific theories, classical myths, contemporary allegories, and notions of the bounds (or lack thereof) of visual thinking and combined them into a stunning work of graphic literature that exists simultaneously as signpost and road, instruction manual and finished product. Pulling from a vast array of sources across time, space, and subject, he examines the nature of text, image, and thought in a way that could only be successfully done "in comic book form." His work could not be performed adequately through text alone, something which his work both illustrates and explains. It's all very deep and intellectual, but with cool pictures.

I wasn't convinced that Sousanis had any clue what he was doing until chapter 2, but once it hit me, I was completely hooked. It was page 37, actually, of the roughly 200-page book (including notes, acknowledgements, and bibliography—in my opinion the work proper was over too soon). Sousanis does not merely proselytize on the benefits of examining new modes of thinking, doing, and learning; he practices what he preaches on every page. There are times when the narration is a bit dry, especially at the very beginning, but as he begins to weave various concepts in and out of the river that is his explanation of dimensionality of thought, the world comes alive both within the book and in the greater world around it. I wouldn't go so far as to say this book opened my eyes to entirely new ways of thinking about the world, but it certainly opened my eyes to entirely new ways of thinking about learning. Sousanis jumps from one source to another, citing and name-dropping and referencing and alluding and generally drawing up the history of human thought to present an understanding of the world that admits a lack of understanding, and it's all very engaging. I was left wishing that more concepts were taught in this way, not only visually, but through a marriage of text and image that makes the best possible use of both. Sousanis plays around with text placement and repetition in an attempt to stretch the boundaries of what is considered practical in a work of graphic fiction, always in aid of the point that he's examining. I've done a poor job of explaining precisely what this book is about, but that's kind of the point: the best way to explain the ideas the book covers is through the visual avenues that the book traverses.

Some people aren't interested in learning, so this book wouldn't be for them, but anyone who is curious, who faces their admitted ignorance with excitement at the possibility of the constant education it implies, they will find joy in Unflattening. We should encourage this type of teaching, because learning should always be this fun. - Brian McGackin

The first thing that struck me as I began to read Nick Sousanis’

Unflattening – the first doctoral dissertation in comics form accepted

by Teacher’s College at Columbia University, and the first comic published by

Harvard University Press – is that I’ve rarely read a comic that wasn’t a

narrative. The only other examples I can think of are Scott McCloud’s

Understanding Comics and its follow ups. Like those, Unflattening isn’t

a story. It’s a monograph, the most beautiful academic essay I’ve ever seen,

complete with cited sources and notes.Artist and educator Nick Sousanis made waves in academic circles last year by presenting his doctoral thesis at Columbia University in the form of a comic book, now released as Unflattening. The medium was vital to Sousanis’s message: a comic which dethrones the primacy of words over pictures in Western thought, and posits comics as an art form which transcends both.

This isn’t Magritte’s “Treachery of Images,” taunting us with “Ceci n’est pas une pipe" (1929). Sousanis is keen to explain; he’s more teacher than provocateur. He describes comics as a way of juxtaposing the visual and verbal in meaningful order. This medium, he argues, helps us to see all things—concepts, objects, abstractions, fantasies, experiences—in relation to one another. Although the implications are profound, Unflattening is less an insurrection than a carefully argued case for rethinking our priorities about art and learning.

Unflattening is above all a humane piece of scholarship which challenges our assumptions about perception. Sousanis reminds us that all art and knowledge are created by beings who inhabit bodies and see the world from a unique perspective, and that every mark on a page or painting was authored by some living hand.

Sousanis works with a wide range of visual and verbal references, drawing imagery from TV and movies, natural science textbooks, and the classical canon of art. In the opening page alone he acknowledges the inspiration of Piranesi’s etchings, set design from the Batman films, and Star Trek: The Next Generation. But this book is neither a geek-fest nor a referential ramble.

With its breadth and ambition, Unflattening doesn’t aim to deeply interrogate every last one of the texts it calls on. Its tone is oracular, and Sousanis’s attempt to leap beyond the limit of mere words leads him, by necessity, away from close textual analysis. Allusions to Bruno Latour and Herbert Marcuse flit past in the kaleidoscope of words and images. An aphorism from Kahlil Gibran bears as much weight here as Deleuze and Guattari. Sousanis compares the process of exploring ideas to that of measuring a coastline: as the length of our measuring unit decreases, we find ever more tiny and subtle folds in the shore. An ant that walks the exact border between sea and land must weave a longer path than a heavy-footed human. Sousanis’s book seeks to outline a vast conceptual geography, and its map can only sketch out some finer points in the territory he surveys. Still, these limitations only challenge us to take Unflattening’s method further. Reading the book, one tries to imagine finely treading the shoreline between the visual and verbal, as an ant would. With Sousanis’s large-scale map in hand, we can seek a way of interrogating both words and images ever more meticulously.

Unflattening’s very first image, on the dedication page, is the double footprint of Sousanis’s daughter, born while he was writing his doctoral thesis. As readers, the author invites us to take our first steps, too: to recognize the many different ways humans have of perceiving, and see the world anew. This is the work of an expectant father, seeking not to limit the future or deny the past, but to unlock doors and invite others to discover their potential. - Matt Finch

In case you haven't noticed by now, this is a very unique book. I was told that Unflattening is the "first doctoral dissertation written and drawn entirely in comic book form," but that's misleading. This isn't a comic book. Nick Sousanis has done something rather incredible: he has taken philosophical concepts, scientific theories, classical myths, contemporary allegories, and notions of the bounds (or lack thereof) of visual thinking and combined them into a stunning work of graphic literature that exists simultaneously as signpost and road, instruction manual and finished product. Pulling from a vast array of sources across time, space, and subject, he examines the nature of text, image, and thought in a way that could only be successfully done "in comic book form." His work could not be performed adequately through text alone, something which his work both illustrates and explains. It's all very deep and intellectual, but with cool pictures.

I wasn't convinced that Sousanis had any clue what he was doing until chapter 2, but once it hit me, I was completely hooked. It was page 37, actually, of the roughly 200-page book (including notes, acknowledgements, and bibliography—in my opinion the work proper was over too soon). Sousanis does not merely proselytize on the benefits of examining new modes of thinking, doing, and learning; he practices what he preaches on every page. There are times when the narration is a bit dry, especially at the very beginning, but as he begins to weave various concepts in and out of the river that is his explanation of dimensionality of thought, the world comes alive both within the book and in the greater world around it. I wouldn't go so far as to say this book opened my eyes to entirely new ways of thinking about the world, but it certainly opened my eyes to entirely new ways of thinking about learning. Sousanis jumps from one source to another, citing and name-dropping and referencing and alluding and generally drawing up the history of human thought to present an understanding of the world that admits a lack of understanding, and it's all very engaging. I was left wishing that more concepts were taught in this way, not only visually, but through a marriage of text and image that makes the best possible use of both. Sousanis plays around with text placement and repetition in an attempt to stretch the boundaries of what is considered practical in a work of graphic fiction, always in aid of the point that he's examining. I've done a poor job of explaining precisely what this book is about, but that's kind of the point: the best way to explain the ideas the book covers is through the visual avenues that the book traverses.

Some people aren't interested in learning, so this book wouldn't be for them, but anyone who is curious, who faces their admitted ignorance with excitement at the possibility of the constant education it implies, they will find joy in Unflattening. We should encourage this type of teaching, because learning should always be this fun. - Brian McGackin

Sousanis’ main argument is that images, in conjunction with text, can help us understand the world around us in ways that are impossible for text to do on its own. Indeed, the format he’s chosen itself works to support the thesis. For Sousanis, it’s all about new perspectives. He uses a visual analogy of eyes working together to produce a stereoscopic view of our environment to demonstrate. Because of the space between them, each eye sees the world from a unique perspective, but only when used together are we able to perceive depth. It takes two different views operating in tandem to come to a new understanding about what’s being observed. And that’s just the beginning of the rabbit hole.

The second thing that strikes me is that, despite this not being a narrative, I can’t help but apply narratives to Sousanis’ stunning images. The book opens with illustrations of human figures moving along a complex system conveyor belts. It’s the assembly line from hell (maybe the DMV?), with signs hung reading “Stay in Line” and “Maintain Proper Distance”. Each figure stands uniformly submissive, with their heads and shoulders slumped. They look sad, and I immediately begin to wonder about them. Who are they? How did they get here? It’s a dramatic image. And the more I think about, the more in awe I am of what Sousanis has accomplished here. I’ve never read a scholarly work that elicited this kind of emotional response from me. To be clear, this is a truly intellectual volume, one which earned its author a PhD in education, but it’s also a very stirring work of art. How many PhDs can say that about their dissertations?

This emotional component adds another dimension to the reading, while simultaneously contributing to his argument. According to Sousanis, part of the reason the world became “flat” is that we’ve lost some of our sense of wonder. Our accumulation of knowledge has accelerated exponentially, leading to increasingly narrow fields of study as we strive to draw in all the edges of the map. We’ve answered most of the big questions, the ones that first stirred us to wonder. Now as we look further out, or more deeply in, we compartmentalize, closing ourselves off from other perspectives. Sousanis is suggesting that a more interdisciplinary discourse is needed in order to come to new understandings about, well, everything. It’s a call to action, that action being to wonder. Ah, but there’s, as Shakespeare wrote, the rub – wonder is both an action and a feeling, speculation and awe. Which is he asking of us? The text points us in one direction, the images move us in another, and the answer appears to be in a magical third space in between.

This is a fascinating achievement. I’m a firm believer in comics’ ability to illuminate the dark corners of the world, to inspire growth and change, the way that all great literature does. But I never imagine comic books functioning as anything other than a storytelling medium. I never consider their capacity to communicate in other ways. What are the limits of its applications? How much longer before we begin seeing the first textbooks in comic book form? Comic book souffle recipes? Legal contracts? Tax forms? I suppose the answer to that lies in our willingness to de-compartmentalize, and step away from our narrow – sometimes strongly-held – views, in order to gain a new perspective. - Joseph Manuel Nieves

Inside Higher Ed Interview: Seeing in New Dimensions

760 WJR Detroit radio, The Relevant University “The Trend of Visual Literacy”

The Chronicle of Higher Education “Amazing Adventures of the Comic Book Dissertator”

review at MIT Center for Civic Media

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.