Steven Hendricks, Little is Left to Tell, Starcherone Press,

Chapter One, available at The Brooklyn Rail

stevenhendricks.com/

This poetic debut novel takes readers down a rabbit-hole through the tales that Mr. Fin, a man with dementia, conjures for his son. In Little Is Left to Tell, rabbits flee bomb-dropping zeppelins. Virginia the Wolf writes her last novel to lure her daughter home and reads its expurgated sections to her captive audience. A rabbit named Hart Crane must eat pages from books in order to speak. Mr. Fin tries to stitch the past together from marginalia and to rebuild his son from boat parts. The haunting fables in this lyrical first novel trace the fictions that make and unmake us.

"Little is Left to Tell ... stands on its own haunches, a powerful meditation on the real and the imaginary, consciousness and family, interspecies friendship, and the imbrications of animal and human experience in landscapes torn apart by violence. The book asks: where do violence and wisdom come from? What will trauma and loss require of the imagination, in order for beings – animal; human; humanimal – to live onward?" - Miranda Mellis

"Like a dream that inhabits an entire life, even a life of reading, this is a deeply rich and surprising novel." - Amina Cain

"We go underground in this book, and keep digging, with hooves and claws, until we've surfaced into a timeless flood that absorbs all of the communiites, animal and imagined, populating this entangled network of narratives that destroys yet refuses to stop regenerating." - Daniel Borzutsky

"Virgina the Wolf devouring little bunnies whole, Hart Crane as a steampunkesque hero, and an old man floating on the seas of dementia are a few of the hallucinatory pleasures that await the reader in Steven Hendricks' debut novel. The classics on future acid, coupled with deep emotion." - Brian Whitener

A tale about the ravages of old age, the weight of the past and bunny

rabbits.

Debut novelist Hendricks tries to apply the whimsical mood of fairy tales to the mildly experimental fiction at play here, and he largely succeeds despite the grim nature of his story. Our protagonist is an elderly man named only as Mr. Fin, who spends his time daydreaming on park benches and tinkering with an old boat; he's clearly suffering from dementia. His only company is a kindly neighbor named Viv, who comes often to check on him. What readers learn is that Fin has a rich inner life, populated by a fanciful cast of animals that includes a bold rabbit adventurer, Hart Crane, and a melancholy writer, Virginia the Wolf, among many other beasts of claw and fang. Fin’s tales (and indeed, the novel itself) also pull liberally from Homer, Cervantes, Hemingway and Virginia Woolf, sometimes (admittedly) borrowing its inspirations sans quotation or citation. Fortunately, all the characters have their own arcs and their own unique journeys—Hart Crane works feverishly to save a family of bunnies who are reeling from a zeppelin attack, while our wolf toils at her last novel in an attempt to lure her daughter home. Things take a dark turn when Fin discovers that, after 20 years, the body of his son David has washed up on the beach. David is strongly implied to have committed suicide, and whether Fin is really attempting to nurse his son back to life or simply worrying after a bit of debris is left hazy. However, as Fin struggles to understand the cipher of his long-lost son, his atmospheric daydreams become more frenzied and insistent than before. It’s a curious experiment but one that carries more emotional weight than most books starring anthropomorphic animals.

A vivid story that uses the language and metaphors of myth to reflect on the unkind nature of age and perception. - Kirkus Reviews

Debut novelist Hendricks tries to apply the whimsical mood of fairy tales to the mildly experimental fiction at play here, and he largely succeeds despite the grim nature of his story. Our protagonist is an elderly man named only as Mr. Fin, who spends his time daydreaming on park benches and tinkering with an old boat; he's clearly suffering from dementia. His only company is a kindly neighbor named Viv, who comes often to check on him. What readers learn is that Fin has a rich inner life, populated by a fanciful cast of animals that includes a bold rabbit adventurer, Hart Crane, and a melancholy writer, Virginia the Wolf, among many other beasts of claw and fang. Fin’s tales (and indeed, the novel itself) also pull liberally from Homer, Cervantes, Hemingway and Virginia Woolf, sometimes (admittedly) borrowing its inspirations sans quotation or citation. Fortunately, all the characters have their own arcs and their own unique journeys—Hart Crane works feverishly to save a family of bunnies who are reeling from a zeppelin attack, while our wolf toils at her last novel in an attempt to lure her daughter home. Things take a dark turn when Fin discovers that, after 20 years, the body of his son David has washed up on the beach. David is strongly implied to have committed suicide, and whether Fin is really attempting to nurse his son back to life or simply worrying after a bit of debris is left hazy. However, as Fin struggles to understand the cipher of his long-lost son, his atmospheric daydreams become more frenzied and insistent than before. It’s a curious experiment but one that carries more emotional weight than most books starring anthropomorphic animals.

A vivid story that uses the language and metaphors of myth to reflect on the unkind nature of age and perception. - Kirkus Reviews

Art to read by…

A couple weeks before reading at Orca Books in Olympia, I invited a number of artists to create work drawing on a 1,000 word excerpt (without context) from the novel.

They created amazing pieces and allowed me to give them away to randomly selected (through child-generated numbers) audience members.

Thanks to China Star, Talcott Broadhead, Johnny Boucher, Rebecca Targ, JC Beldin, Whitney Evanson (image coming soon), and Ruth Hayes (image coming soon).

Artist: China Faith Star

Virginia thought about her daughter, for she needed to think her way through the strange city she’d drawn from Jinny’s own stories. Whatever she’d taken she had made her own, but still, as much as her work was her escape, her meditation, she was haunted by her daughter’s creations, and they made her book a troubled thing.

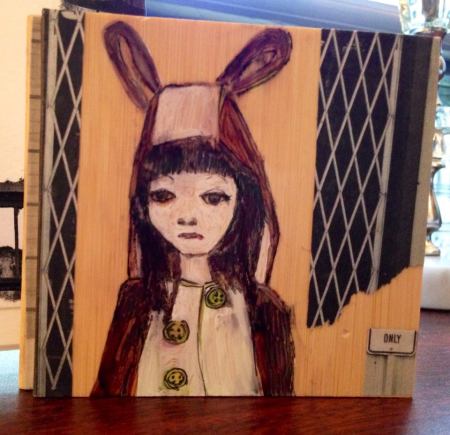

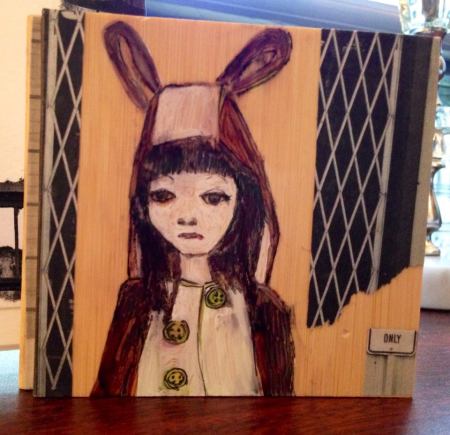

Artist: Talcott Broadhead

Here, she thought, at this moment, no one on the earth can see me, and no one thinks of me but me. She listened for her name in the faraway air, along the limbs of the airship. I’m invisible, she thought, except to the ship, the tree-bird knows I’m here, and carries me.

She was living ink on living paper, and she was part of the conversation in the sky’s humors, so that around her, crisply serifed letters relayed her thoughts to another world, told her story.

Artist: Johnny Boucher

…the sour clockwork of the zeppelin growled into action.

The chewing shook the wreckage all around her, and Mother ventured from her shelter, clambered up to the top of the shifting pile. A quick look and she saw no other rabbits, none of her children. But it was dim

Artist: Rebecca Targ

As for the other rooms of the house, which seemed to lack innate functions, they were more, to the salmon children, like game boards, surfaces and pieces that signified something else, variables—the functions and the rules of which needed discovery. Properly arranged, a harmony might be achieved. Would there be answers? The possibility occurred to them, but they hadn’t managed to formulate questions.

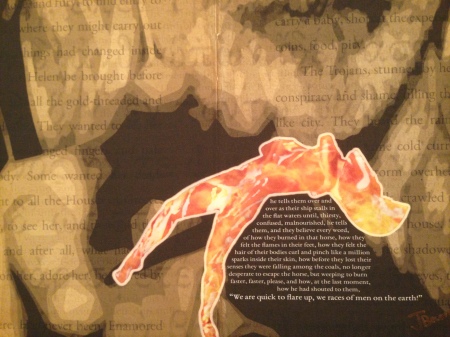

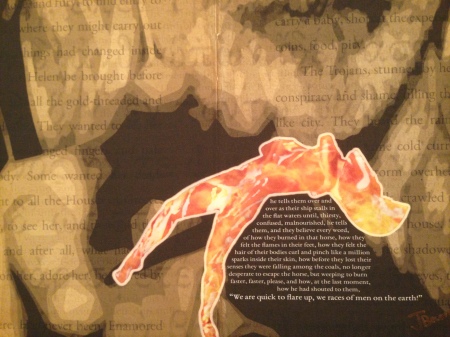

Artist: JC Beldin

…he had shouted to them, “We are quick to flare up, we races of men on the earth!”

All along, despite Athena’s love for him, Odysseus did not suspect that he was the hero of a legend. All along he believed he would die alone, that his story, once told, would shame his family, and expose him as a thief, a liar, a coward, a fraud. Instead, he lives on as the blind bard, repeating his tale to be rid of having lived it. He lives on as the figure of all authors who transmute their speech into the dead earth of the novel.

As his connection to the world fades, old Mr Fin finds a measure of delight in the vividness of memories that crop up, especially the stories he used to invent for his long-lost son, David.

From the half-remembered bedtime stories and scenes from The Odyssey, The Old Man and the Sea, Don Quixote, work by Maurice Blanchot, Hart Crane, Mallarmé, and lines from Virginia Woolf, Mr Fin draws the materials he needs to approach the limits of his life.

But as the stories press upon him, the possibility that he might reconnect with his son leaves him isolated in his home, searching in books and in his and David’s troubled past for some peace, some way to soothe the troubled characters of their broken world of stories.

The stories are overwhelming, multiplying and repeating patterns like a fugue: a family of rabbits, searching for a place to bury their eldest brother; a flying tree that carries our heroes but can’t save them; a bear half-eaten by a colony of ants, searching for a book; zeppelins of iron and flesh that devour cities; the big-bad wolf—now domesticated as pulp-fiction writer Virginia the Wolf, finishing her last novel; Hart Crane, a rabbit who eats printed words and speaks in poetry; Orpheus and Eurydice, adventurers between the world of the living and the dead; Odysseus, hatching new plans after the horse has failed; an alphabet trapped in the mind of a goat-boy; a young wolf who must brave the path through the woods to her grandmother’s house; fish-children, alone in an abandoned village, who must reinvent the world.

“As silent as a mirror is believed

realities plunge in silence by”-Hart Crane

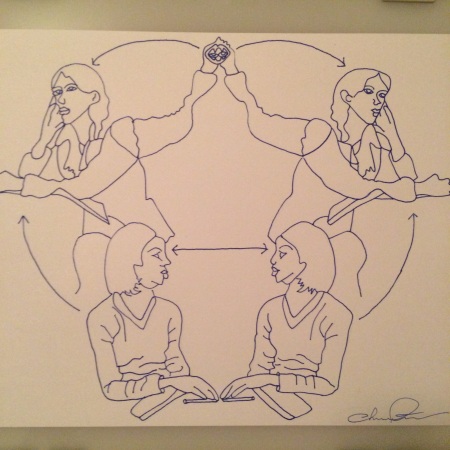

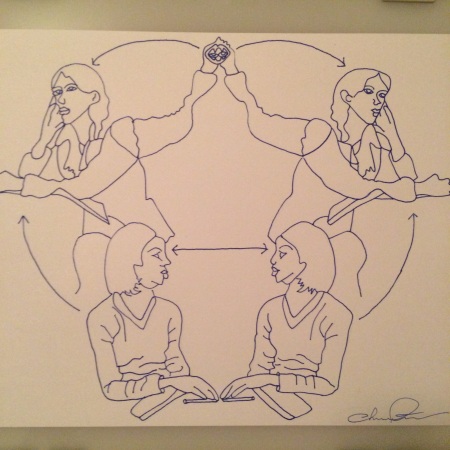

I took the title, Little is Left to Tell, from Beckett’s entr’acte, Ohio Impromptu, an 11-minute play staged with two identical actors seated across from one another at a table. Only one speaks throughout the play, and only to read from a book. “Little is left to tell…”, he begins, recounting a loss and a grief to the other, whose only action is to knock on the table when he wants a line repeated. Eventually, there is nothing left to repeat, and the end must arrive.

They created amazing pieces and allowed me to give them away to randomly selected (through child-generated numbers) audience members.

Thanks to China Star, Talcott Broadhead, Johnny Boucher, Rebecca Targ, JC Beldin, Whitney Evanson (image coming soon), and Ruth Hayes (image coming soon).

Artist: China Faith Star

Virginia thought about her daughter, for she needed to think her way through the strange city she’d drawn from Jinny’s own stories. Whatever she’d taken she had made her own, but still, as much as her work was her escape, her meditation, she was haunted by her daughter’s creations, and they made her book a troubled thing.

Artist: Talcott Broadhead

Here, she thought, at this moment, no one on the earth can see me, and no one thinks of me but me. She listened for her name in the faraway air, along the limbs of the airship. I’m invisible, she thought, except to the ship, the tree-bird knows I’m here, and carries me.

She was living ink on living paper, and she was part of the conversation in the sky’s humors, so that around her, crisply serifed letters relayed her thoughts to another world, told her story.

Artist: Johnny Boucher

…the sour clockwork of the zeppelin growled into action.

The chewing shook the wreckage all around her, and Mother ventured from her shelter, clambered up to the top of the shifting pile. A quick look and she saw no other rabbits, none of her children. But it was dim

Artist: Rebecca Targ

As for the other rooms of the house, which seemed to lack innate functions, they were more, to the salmon children, like game boards, surfaces and pieces that signified something else, variables—the functions and the rules of which needed discovery. Properly arranged, a harmony might be achieved. Would there be answers? The possibility occurred to them, but they hadn’t managed to formulate questions.

Artist: JC Beldin

…he had shouted to them, “We are quick to flare up, we races of men on the earth!”

All along, despite Athena’s love for him, Odysseus did not suspect that he was the hero of a legend. All along he believed he would die alone, that his story, once told, would shame his family, and expose him as a thief, a liar, a coward, a fraud. Instead, he lives on as the blind bard, repeating his tale to be rid of having lived it. He lives on as the figure of all authors who transmute their speech into the dead earth of the novel.

* * *

Scarcely able to see well-enough to read, Mr Fin nevertheless

indulges in old familiar novels, classics that he can recompose from a

bit of text.As his connection to the world fades, old Mr Fin finds a measure of delight in the vividness of memories that crop up, especially the stories he used to invent for his long-lost son, David.

From the half-remembered bedtime stories and scenes from The Odyssey, The Old Man and the Sea, Don Quixote, work by Maurice Blanchot, Hart Crane, Mallarmé, and lines from Virginia Woolf, Mr Fin draws the materials he needs to approach the limits of his life.

But as the stories press upon him, the possibility that he might reconnect with his son leaves him isolated in his home, searching in books and in his and David’s troubled past for some peace, some way to soothe the troubled characters of their broken world of stories.

The stories are overwhelming, multiplying and repeating patterns like a fugue: a family of rabbits, searching for a place to bury their eldest brother; a flying tree that carries our heroes but can’t save them; a bear half-eaten by a colony of ants, searching for a book; zeppelins of iron and flesh that devour cities; the big-bad wolf—now domesticated as pulp-fiction writer Virginia the Wolf, finishing her last novel; Hart Crane, a rabbit who eats printed words and speaks in poetry; Orpheus and Eurydice, adventurers between the world of the living and the dead; Odysseus, hatching new plans after the horse has failed; an alphabet trapped in the mind of a goat-boy; a young wolf who must brave the path through the woods to her grandmother’s house; fish-children, alone in an abandoned village, who must reinvent the world.

“As silent as a mirror is believed

realities plunge in silence by”-Hart Crane

I took the title, Little is Left to Tell, from Beckett’s entr’acte, Ohio Impromptu, an 11-minute play staged with two identical actors seated across from one another at a table. Only one speaks throughout the play, and only to read from a book. “Little is left to tell…”, he begins, recounting a loss and a grief to the other, whose only action is to knock on the table when he wants a line repeated. Eventually, there is nothing left to repeat, and the end must arrive.

Steven Hendricks's work has appeared in The Denver Quarterly, Web Conjunctions, Fold: The Reader, The Encyclopedia Project (Vol. 2), Sidebrow, and at XCP . He is a practicing bookbinder, book artist, and letterpress printer. He lives in Olympia, WA, with his wife and two children, and teachers writing, literature and book arts at Evergreen State. Little is Left to Tell is his first novel.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.