Ermanno Cavazzoni, The Nocturnal Library, Trans. by Allan Cameron, Vagabond Voices, 2013.

Ermanno Cavazzoni admits that his books push the novel to its very limits — “like outpourings of the maniacal”, he says. “That’s how they come to me, you must understand.”

Here in The Nocturnal Library, we have the maniacal that we all know from our own dreams: a dreamer’s lack of control and a dreamer’s dogged acceptance of the absurd. Here we have the dream as paranoia and the vain struggle to understand the rules that govern life. Here we have the dream as a bizarre library in which the fragility of human knowledge is emphasised again and again.

Jerome, who perhaps represents the archetypal man of learning, is bound up in his world of books and suffers from crippling insomnia. He has to study for an exam, and his troubles are compounded by bad toothache, or at least these are the dominating themes of his dream. The reality of wakefulness only appears in the last paragraph of the last chapter.

But this is not primarily a book about dreams. Amongst other things, it is a book about the arrogance and illogicality of power and bureaucracy, and the relationship between the world of intellectual order and the chaos of nature, dominated as it is by mutual disregard and the latter’s inevitable victory in the long term.

And above all, this is a book in which fantasy reigns for its own sake and goes wherever the author’s creative impulse takes it. That is how his novels come to him, and you have to understand that! If you do, you will enjoy this exotic book.

A fantastic evocation of life and learning in a dream sequence: Jerome, who has to sit an exam and suffers from toothache, enters a nighmarish library in which everything conspires to frustrate his desperate attempts to revise. Cavazzoni creates an entire world in this dream, whose absurd perhaps comments on the more muted absurdity of reality. The library contains geological and natural realities that plague the organic matter of which the books are made, demonstrating or at least suggesting the futility of human learning. In some parts of the building the books have turned into peat. Cavazzoni admits that his books pushe the novel to its very limits - "like outpourings of the maniacal," he says. "That's how they come to me, you must understand."

Ermanno Cavazzoni, Voice Of The Moon, Trans. by Ed Emery, Serpent's Tail, 1990.

The madness particular to all those who come under the influence of the city of Padua is celebrated in this novel by Italian writer Ermanno Cavazzoni. Savini, the central character, finds himself the victim of even more alarming circumstances at the time of the full moon.

Savini is exploring the countryside to gather information about a strange phenomenon: people have been finding messages in bottles at the bottoms of wells and hearing voices coming up from these wells. What follows is a belabored account of Savini's discovery that people are really actors and their houses made of cardboard, that they will come out, put on a show and then laugh about what a fool they have made of the audience. Savini meets up with a prefect, and together they set out to expose these actors as well as the hidden creatures they believe are residing at the brink of reality, latching on to human thoughts and bodies. As the novel unfolds in a surreal succession of episodes, we encounter a man who has intimate relationships with his kitchen appliances and a woman who is able to transform herself into a cockerel as part of a mating ritual. Although the Italian author's writing is amusing, the action is repetitious and the appeal of the characters is severely limited by their unrelenting paranoia about the bizarre and ultimately meaningless happenings around them. This novel was recently made into a movie by Federico Fellini. - Publishers Weely

Fellini the Lunatic and His Last Film 'Voice of the Moon'

Ermanno Cavazzoni, Brief Lives of Idiots, Trans by Jamie Richards, Wakefield Press, 2021.

Brief Lives of Idiots is indeed a collection of pieces about people who are, in various ways, mentally enfeebled, ranging from those whose intellectual growth has been stunted to those who become preöccupied with an idée fixe to a few examples of people simply acting very foolishly. (Yes, the chapters focusing on those with actual physical disability in the form of limited mental capacities -- such as one on 'The Republic of Born Idiots', about the Bastuzzis, "a community of idiots left to their own devices" -- can make for somewhat discomfiting reading nowadays, but most of the pieces feature characters whose idiocy is of a different nature.)

As Cavazzoni explains in a 'To the Reader'-preface:

What follows is one calendar month. Each day holds the life of a kind of saint, who experiences agony and ecstasy the way traditional saints do.

There are thirty-one pieces in this sort of calendar of lives, in imitation of a typical 'lives of the saints'-collection but with a rather different (and, in some ways, not so different) cast of figures. Most of the entries do center around individuals, though in some -- as with the aforementioned Bastuzzi family -- the portraits do extend beyond a single individual. Bolstering the cyclical calendar-feel, every seventh entry is of a somewhat different form, basically not dedicated to an individual idiot but rather focused, more or less, on suicides; most of these include several, rather than just a single example.

The idiocy of most of the lives described here is one of some kind of foolishness. The figures tend to the obsessive or repetitive, focused on one thing or idea, often to the bitter end: 'The Martyr to Feet' finds a Dr.Dialisi's life destroyed after buying a pair of shoes that struck his fancy but proved painfully too small for his feet: he can't let go, or have them fixed, and: "whereas he used to be a man without any interests or desires, from then on he became a man who thought of nothing but his shoes". As happens with several of the fools in this collection, it's an obsession that eventually kills him.

Some of the characters seem to have led relatively normal, full lives before cracking, while others have always been this way; either way, the conclusion of one of the pieces goes for almost all of them:

That was her life. Nothing else happened.

If some get stuck in their loop of obsessed sameness, others' foolishness manifests itself in suddenly new-found ambitions. The opening tale finds a Mr. Pigozzi reading about someone's 1976 escape from East Germany in a homemade airplane made from old car parts -- and:

Since Pigozzi had an old Fiat and didn't get along with his wife and daughter, he started playing with the idea of taking off one day and never coming back.

Typically, however, his efforts fall short; Pigozzi proves not to be, as the title of the piece had suggested, 'The Aeronautical Expert'. Part of the fun of Cavazzoni's pieces is not merely in his characters' failures, but in how they fail; not only is Pigozzi's escape-attempt a complete failure, it isn't even recognized for its grandeur and ambition: one witness doesn't recognize his would-be plane as a flying machine and simply thought: "he was trying to mow the lawn" with some newfangled machine, while his family then tells everyone that his spectacular crash was a simple car accident.

The suicide-pieces are slightly different from the rest, but particularly good fun. Each of the four is a variation on the theme, with the first, for example, describing 'Working Suicides' -- people who kill themselves in some work-related way, down to the creative:

A professor of Roman law provoked a nervous student so much during an exam that the latter grabbed the gavel on his desk and hit him in the face and then the temple. The professor had wanted to die for some time; he said no one needed Roman law anymore and that it only served to torture professors and students from generation to generation.

Here too, as well, Cavazzoni finds cruel twists to take the wind out of the sails of the suicides' hoped for moment of significance and glory, as in:

A poet who composed meaningless poems using a calculator committed suicide by gas inhalation to give his poetry a general sense of drama. But the police report simply states he left the gas on, possibly by accident.

The second set of suicides collects 'Collateral Suicides', where the hapless ones trying to do away with themselves manage to inadvertently take someone with them; a third set focuses on 'Near Suicides', where most of the figures have second thoughts at the last moment; while the final one describes 'Star-Crossed Suicides', yet another example of would-be suicide going all wrong.

The foolishness of the idiots collected here ranges from a man obsessed by the speed at which the earth is moving through space -- an insane 108,000 kilometers an hour, after all -- to 'Luigi Pierini, Calculating Prodigy' (who can't quite do enough with his remarkable talent) to 'The Failed Whore'. The one who can't get over how fast the earth is moving can't help but conclude that: "We're a bunch of nuts" -- but he means all of mankind, unperturbed by the speed at which everything is going by; of course, in reality he is the odd man out, just like the rest of these idiots, fixated on something in a way that sets them apart from going on with life as normal, as most everyone else is able to do.

The variations are entertaining, and some are very clever -- and one truly haunts, described in 'Memories of Concentration Camp Survivors'. The fool in that case spent two years at Mauthausen during the Second World War -- without recognizing that as such, or his experiences as unusual. Even his own emaciated condition, and that of the other prisoners, doesn't strike him as strange:

He was very thin when he went in, since everybody in Pescarolo had been thin for ages, as it's such an underdeveloped area. The other people in the concentration camp were thin too. He didn't know where they were from, so he thought it was just a general attribute of the population.

A neat little collection, especially for dipping into, a few pieces at a time. - M.A.Orthofer

https://www.complete-review.com/reviews/italia/cavazzoni.htm

Non-Italian readers probably don't know Ermanno Cavazzoni at all. Even many italian readers probably don't know him (Italians are not great book readers). Here is a brief description of Cavazzoni in English. And here is a Cavazzoni's short story - a funny, absurd, fairytale writing - translated to English.

Cavazzoni writes not so popular books. He gained some popularity when Federico Fellini in 1990 made a film out of his book "Il poema dei lunatici" (English translation "Voice of the moon"). A few more of Cavazzoni's books are translated to English.

I read all of his books and so when I knew a new Cavazzoni's novel was out I bought it as soon as I could. The new book is "La galassia dei dementi" (The Galaxy of Madmen) and, unexpectedly, it is a very long novel that looks like a sci-fiction one. I have not read yet the 660 pages of this novel but I know it is not what we can identify as "sci-fiction", even if it is set in the year 6ooo A.W. (After the Invention of the Wheel - but the date of the invention of the wheel is not exactly known, and it's placed around the 4th-5th millenniun BC, so...).

Anyway, I just want to introduce to you this important italian writer. What kind of reader can appreciate Cavazzoni's books? As I said, his novel are not the very popular kind. He writes absurd, weird and somehow funny stories using a very simple language. People who like writers like Cortazar, Borges, Perec, Queneau - or the american Nicholson Baker - could appreciate Cavazzoni too, probably.

A list of titles of Cavazzoni's books can help you to understand what I mean:

- The Poem of Lunatics

- Short Lives of Idiots

- The Useless Writers

- Eulogy of Beginners

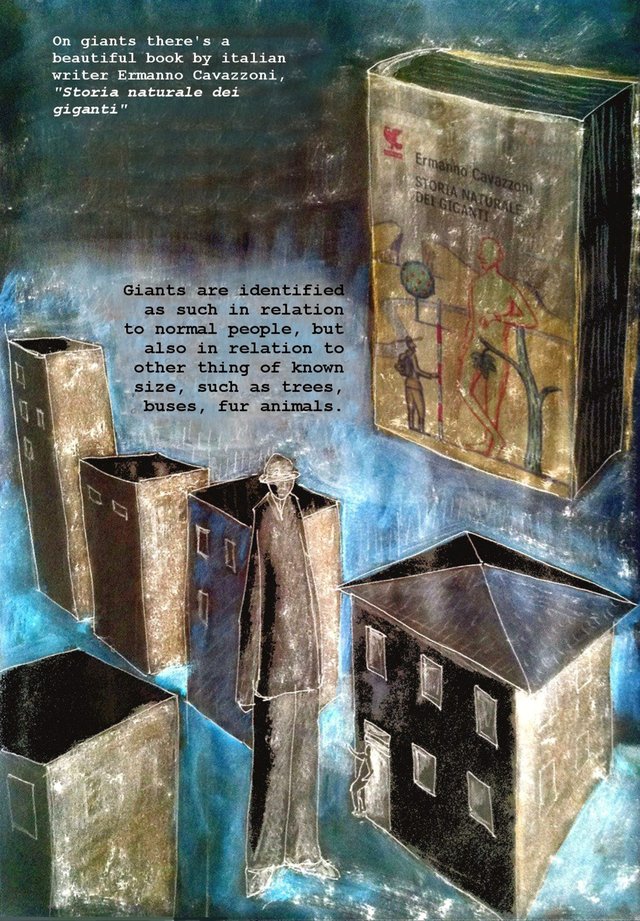

- Natural History of Giants

- The Limbo of Fantastications

- A Guide to Fantastic Animals

- The Valley of Thieves

- The Lonely Thinker

- paolobeneforti

https://steemit.com/books/@paolobeneforti/a-new-novel-of-a-great-italian-writer-ermanno-cavazzoni

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.