https://hobohemiadotblog.wordpress.com/

Resurrecting a lost Jazz Age novel from literary obscurity

Maxwell Bodenheim, Georgie May, 1928.

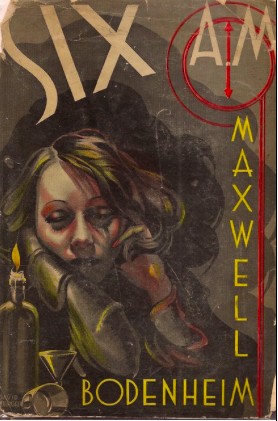

Maxwell Bodenheim, Six A.M., 1932.

One of my passion projects was to try and bring Maxwell Bodenheim’s work back into the marketplace. His 1932 novel, 6 A.M. came and went when it was published, hardly making a stir from jaded critics and readers before it quickly fell out of print.

Long out of print since its first publication by Horace Liveright, Inc. in 1932, poet-novelist Maxwell Bodenheim’s lost novel, SIX A.M. is the story of sixteen hours in the lives of a motley crowd, living and visiting in the shadiest Broadway hotel imaginable.In the strange salon there maintained by Harold Loomis, butterfly of the night, two women struggle for his love. There too, in Room 416, Temple, a novelist, makes a wager with Kranzberg, a bootlegger, that he can take a vicious, hard-boiled girl from the curious salon that Loomis maintains, and bring about her regeneration. If he fails, he will commit suicide at 6 A.M. A society girl and a burlesque show queen play their parts in the dramatic evening. Sailors, actresses, business men, writers, gold-diggers and vagrants add color to the scenes. And the girl to be saved brings about an ironic and intense denouement in a novel of absorbing interest.

The scarcity of 6 A.M. meant that even scholars, not twenty years after it was published, and working on dissertations of Bodenheim’s life and work were able to locate a copy. - hobohemiadotblog.wordpress.com/2019/02/20/maxwell-bodenheims-lost-novel-6-a-m-now-available/

I was reading a journal of Jack Kerouac's, from August 1951 when I first came across the name of Maxwell Bodenheim. Kerouac was out carousing and drinking with friends, including Allen Ginsberg when he ran into Bodenheim at a bar. The pair brought Bodenheim with them to the recording studio of Jerry Newman. Newman proceeded to record the poets reading from their poems. Bodenheim fell asleep on the floor while Ginsberg read of "The Shroudy Stranger." Bodenheim woke and the trio left and returned to Bodenheim's cold-water flat in a Bowery rooming house where they were thereafter kicked out to the street for making too much noise.

Intrigued, I wanted to know more about Maxwell Bodenheim. Who was he? Was he ever published? Was he still alive? Searching the Internet, I found that he was long gone, of murder in 1954. He was dead and, apparently, so were all of his books, fourteen novels and ten books of verse. He was, I learned, a Jazz Age poet of notoriety who was once the "King of Greenwich Village." He was now tabloid fodder, and of this, it was all that was left of this troubled genius's legacy.

There are numerous sites that duly document Bodenheim's peccadilloes and foibles, describing his dalliances with young women, some of them tragic. There was his flirtation with Communism that all but blacklisted him from not only the publishing industry, but also working for the Workers Progress Administration which kept him in sustenance. Bodenheim had burned every bridge that could have lead him to a lifetime of relative comfort and sustenance. He pissed off critics, fellow poets, women, wives, and family. One-by-one they backed off creating what one critic described, a "conspiracy of silence."

One-by-one, Bodenheim's books dropped off the shelves, either making it as far as a sleazy pulp paperback (Georgie May, A Virtuous Girl, Naked On Roller Skates), or to die untimely (6 AM, Slow Vision) to stay out-of-print to this day. Bodenheim, desperate and starving, eventually sold off the rights to his works and lived out his remaining years in poverty and a waning literary reputation. He had become a ghost of the Jazz Age, resigned to begging for drinks and coffee in Greenwich Village.

In February 1954, Bodenheim was murdered, along with his third wife, Ruth Fagan, after being taken in off the cold wintry New York streets by a deranged dishwasher. Bodenheim took a bullet to the heart and Ruth Fagan was savagely stabbed to death. The murderer, Harold Weinberg, attempted to flee to elude authorities on an interstate chase, but soon returned to New York without a cent to his name.

Though there was an immediate attempt to cash in on Bodenheim's infamy with a trashy book reputedly authored by Bodenheim (My Life and Loves in Greenwich Village, authored instead under the auspices of notorious Samuel Roth), the rest of Bodenheim's books slowly disappeared . . . for good.

Learning this, and developing a growing interest in the life and work of Maxwell Bodenheim, I initiated my interests with an all-encompassing blog that would attempt to give some scope to the entirety of Bodenheim's life. I collected what books I could find until two years later when we had found all of his work, some of them very rare. Many were signed and/or inscribed by Bodenheim. It is a rare time, a writer waiting for rediscovery and his books, signed or otherwise, that can still be had for a bargain.

My other goal was to try and put his books back into print. I didn't want to wait for the time, if ever, that this would happen. All of Bodenheim's work is in the public domain. I started first with Bodenheim's first novel, Blackguard, and then Six AM (an especially rare book, as it has eluded the first two of Bodenheim's biographers who were unable to locate a copy less than ten years after his death.

For the next novel, Georgie May, I wanted to make it an exceptional reprint and include letters, reviews and other related material to accompany the book. With your help, I can make this happen.

Bogie deserves rediscovery of his work, and I think you will be pleased with his keen discerning insight into human heart.

Please check out my blog devoted to the life and works of Maxwell Bodenheim here.

Cheers!

"I am a distinguished outcast in American letters — a renegade and recalcitrant, hated and feared by all cliques and snoring phantom celebrities, from ultra-radical to ultra-conservative — an isolated wanderer in the realm of intellect and lithely fantastic emotion, hemmed in by gnawing hostilities and blandly simulating venoms . . ." - Maxwell Bodenheim

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/paulmaherjr/resurrecting-a-lost-jazz-age-novel-from-literary-o?ref=user_menu

“What Is This Thing Called Love?” Sings Maxwell Bodenheim and Even the East River Bridges Are Moved

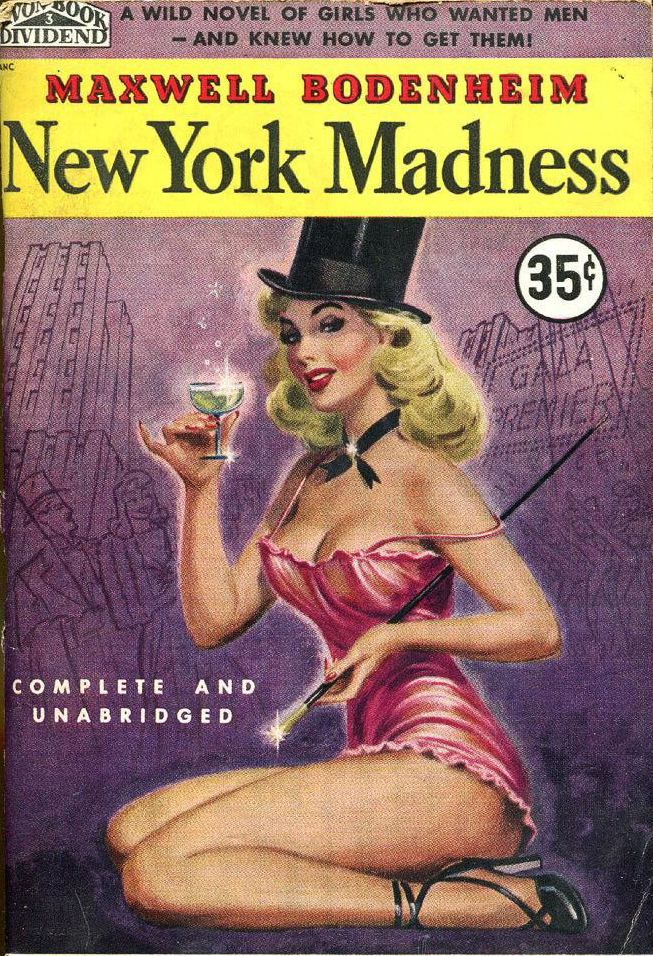

“Maxwell Bodenheim in “New York Madness” (The Macaulay Company) arrives at the conclusion that while such a thing might be, life has become too complex, too exacting ever to allow a man and a woman dwell together in a completne contentment.

At least, that seems to be the burden of his story, for at the end, when Mona has decided that she loves the crippled Emil, after all, the ruthless Mr. Bodenheim causes the disheveled and hysterical Alicia to come staggering back to the apartment in time to wreck an hour-old Harden of Eden with the frightened statement that her Joe, on the spot, had committed suicide chiefly because life wasn’t worth living, just hanging around to scrap with her.

The same preoccupation with the race’s sexual problem which characterized “Replenishing Jessica” and “Georgie May” rages feverishly throughout “New York Madness,” but either Mr. Bodenheim is getting older or he has undertaken a self-discipline which a Matthew Arnold would have called “Literary restraint.” Both Alicia and Mona, even Joe, the speakeasy proprietor, and Emil, the crippled newsdealer, are gifted with volcanic passions. Mr. Bodenheim still seems to think it is a great pity they may not be in continual eruption, like so many Vesuviuses. The boredom of human existence exasperates him. However, I think in this book he reveals more clearly than in any of his other novels that at heart he is a small boy whose fondest wish is not to worship at the shrine of Venus with odes, libations and reverences, but rather with skyrockets, Roman candles and firecrackers. In his ecstacies he seems to have an urge to clap his hands and cheer. Again he is his own most enthusiastic audience. But slightly subdued, if you please.

Wandering Bridges

He takes the reader from “sin spot,” as the columnists call them, to “sin spot.” He sits apart, using Alicia and Mona and their gentlemen friends to prove that alcohol is but an anaesthetic for ennui, certainly a not very original observation. He is deeply interested in the vagrant attraction of one for another, skillfully masked behind the conventional subterfugues of small talk. This may be a sign that Mr. Bodenheim is growing up. At least he has overtaken Honore Balzac at last and is now treading on the heels of Guy de Maupassant.He is at his best in this book when he sharpens his knife upon the literati, gathered for a lark after rendering honor to one who is so obviously Pearl S. Buck that lest, by not mentioning her name, we fail in the identification, he describes this “white lady from China” as one “who had written an enormously best-selling, sentimental, placidly flowery and pathetic version of a Chinese farmer’s rise to power and influence in his locality––a book in the ‘undangerous’ and earthly simple category.”

The book reviews in the New Yorker irritate him to a wordy frenzy. So do the Communists, although he introduces Mona to Emil in the heat of one of their smaller riots with the cops. The stool pigeon, the vice squad and the fixings which alarmed New York but a short while ago make their appearance early and as early make their exit. The frameup for a while seems to have left its scars upon Mona and Alicia, but wearying of such crusading missionary work Mr. Bodenheim moves on to more universal problems, such as a reason for men and women saying one thing and thinking another, etc.

Both the girls are scarlet creatures, half-pagan, half-repressed. Beneath their tinsel each has the heart which is perpetually on the gold standard. You will be amused by Alicia’s explanation to Joe that, while she has always been a gold-digger, at heart she never was.

Meekle, the straight-thinking liberal of Columbia Heights, is inclined to get a bit beyond Mr. Bodenheim at times, the reason being, no doubt, that Meekle is always reasonable, even when ducking out of Jose Marranza’s pool room to avoid a beating up after a brawl. But I wonder how long ago it was that one of the East River bridges left its moorings to move down to Atlantic Ave.

“Miguel Romalos, nicknamed Meekle, lived in the dirtier and less respectable part of Columbia Heights, one short block away from the foot of Atlantic Ave. –that lower part of Brooklyn hemmed between the shadows of two great bridges and confronted . . . by . . . the uplifted, gray talons of Manhattan’s downtown district,” we read, which reminds me I must take a stroll along the water front to check up on the wonders wrought by time. Or is it that Mr. Bodenheim has confused Atlantic Basin with Wallabout Market and the Navy Yard?

To be sure, so far as the fortunes of Meckle and the girls and Joe and Emil, not to mention Tom and Stan, are concerned, it doesn’t matter. Mr. Bodenheim has his district dead to rights, even if he has seen fit to exercise a curious poetic license by moving great bridges about like pawns and rooks, to suit his momentary necessities. - hobohemiadotblog.wordpress.com/2019/02/21/book-review-new-york-madness-august-30-1933/

“White Collar Workers Facing Crisis is Theme of Bodenheim Novel”

In the earlier stages of his career, Maxwell Bodenheim was more rightly known as a poet than as a novelist. The most impressive of his earlier writings were to be found in his first two volumes of verse, “Minna and Myself,” and “Advice.” In these, he produced tender and individualized romantic love poems, and utilizing many of the familiar themes of poets, such as death, he treated them with a subtlety and metaphorical originality which resulted in genuine freshness.

In his succeeding volumes of verse, he stiffened up, overdrawing and attenuating his subtleties and allowing his metaphorical originality to run into too much verbal license. Exceptions to this development in his verse were some of his jazz poems which recreated a real use of jazz age atmospheres in the rhythms and movements of jazz. In the earlier stages of his career, Maxwell Bodenheim was more rightly known as a poet than as a novelist. The most impressive of his earlier writings were to be found in his first two volumes of verse, “Minna and Myself,” and “Advice.” In these, he produced tender and individualized romantic love poems, and utilizing many of the familiar themes of poets, such as death, he treated them with a subtlety and metaphorical originality which resulted in genuine freshness.

Since Bodenheim has turned into the wholesale production of action, his poetry seems to have lessened, and if we compare “Slow Vision” with some of his recently published efforts at revolutionary poetry such as “Revolutionary Girl” in the New Masses, it is apparent that the former is now outrunning the latter. Previous to this book, the most satisfying of his earlier novels was unquestionably “Georgie May”, the story of a southern prostitute. Although he inclined to over-sentimentalize his feminine characters, and to interrupt his narrative progress with needs authors’ asides, his characterization survived and we were given a plausible picture of this girl’s life, her background, her unchannelled and unanalyzed bitterness.

Sociologically, “Slow Vision” is one more document added to that accumulating pile which informs us of what is happening in present day capitalistic America. Here we see two white collar workers, Ray Bailey and Allene Baum, summed into the depression with unemployment, speed-ups, discouragement on every side. Their story runs a natural and inevitable course. They offer resistance after assistance to a growing impulsion towards radical and revolutionary impulses. They try to convince themselves that maybe they, if not others of their class, can forge ahead. They offer jingoistic phrases to cool their growing doubts.

They piously hope that some reformist politician will make America honest, and that they will profit from such a moral cleansing. And int he end, with their hopes unfulfilled and their doubts overcoming their resistances, they move towards a Red union, he taking the lead, and she following after him because of their love.

Bodenheim tells this story naturally, and the gravitation of his characters towards a revolutionary stand is unforced, and implicitly a part of their lives as he depicts them. In building up this story, he surrounds it with a sympathetic account of their love, the way they are granted no privacy, and must sit on park benches and meet the curious glances of strangers, and the menacing stares of cops. Also, he stresses the effects of work and fatigue on his characters, the way it impels them towards a search for over-stimulation and for the forgetfulness that can be achieved in drink, in sex, in quibbling quarrels.

In a sense, the theme of this novel also recapitulates and reveals something of Bodenheim’s own development. In much of his earlier work, he blindly stabbed out in the expression of a resentment and unchannelled bitterness which he felt, and which he put into the mouths of various characters. At one stage of their career, his protagonists here give voice to the same feelings. They gravitate beyond them to a revolutionary position just as Bodenheim reveals that he has. Thus he is here able to establish the social background to his story more firmly than in some of its predecessors. And he does not force his endings by needling in an attenuated subtly, or by hammering over melodrama as in other novels. Rather, the denouement rides naturally out of the story and the author’s viewpoint.

Bodenheim writes with ease. His descriptions of the work-worn crowds flowing homeward over the pavements, of the crowds in the parks at night, of Union Square are all done with effect. However, in a few descriptive passages of passing importance, he relapses into an old mannerism, in which he combines anthropromorphism and gratuity to produce a description that is merely wordy: “The beginning of night in late March had a subdued coolness, the reluctant compromise between winter and spring with one putting on its best front to say good bye and the other diffidently acceptant, a meeting always robbed of its inherent gaiety and plaintiveness, in any large, American city, by a factor difficult to define in its external contrasts and yet unmistakable underneath.”

Also, in passing, it should be added that in establishing the effect of work and fatigue on various characters, he relies on a number of explicit statements which beat like a refrain, producing a certain amount of over-statement. These criticisms notwithstandingly, “Slow Vision” is decidedly the best of Bodenheim’s novels, and it is symptomatic of what is happening at the present time in our American cities.” (Daily Worker) - hobohemiadotblog.wordpress.com/2019/02/24/slow-vision-review-daily-worker-november-29-1934/

During the first third of the 20th century, Maxwell Bodenheim enjoyed a reputation as both a poet ranking with Ezra Pound and Edgar Lee Masters and an obnoxious caricature of the Great Lover. Born in Hattiesburg, MS, Bodenheim received no formal education. He falsified his age to enlist in the Army. There, a lieutenant ridiculed Max as a Jew. Private Bodenheim slugged him with a rifle, leading to six months in the guardhouse. This and other events led to an eventual dishonorable discharge.

Max drifted to Chicago, where he met Ben Hecht. Then a daily newspaper reporter living the life he later distilled into The Front Page, Hecht published the Chicago Literary Times, "the bull-in-the-bookshop," a hair-raisingly radical review inspired by anti-establishment critics H.L. Mencken and James Gibbons Huneker. Bodenheim came to Greenwich Village as the CLT's eastern correspondent. In The Improper Bohemians, Allen Churchill ascribed the move to the contrast between morally conservative Chicago and Greenwich Village, which was, as Jacob Rachlis told Jeff Kisseloff for You Must Remember This, a pretty freewheeling place. Thus began, as Kisseloff wrote, Max's "equally long trails of empty bottles and broken hearts."

Through the 20s, Bodenheim's novels, such as Georgia May, Replenishing Jessica, and Naked on Roller Skates, were controversial and often popular. He had published several collections of verse, and his poems frequently appeared in fashionable magazines. Given his present obscurity, Bodenheim's reviews are astonishing. For example, Burton Rascoe, the literary editor of the New York Herald-Tribune, then called him "?the Rimbaud of the arts, a remarkable and gifted poet."

In 1926, Bodenheim and his publisher, Horace Liveright, were hauled into court by John S. Sumner of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. Sumner, Anthony Comstock's successor as champion of bigoted morality, had suppressed James Joyce's Ulysses in 1920. Now he claimed Replenishing Jessica, whose heroine found "the simple feat of keeping her legs crossed?a structural impossibility," was obscene and indecent. This time Sumner's case was dismissed, although not before it had unwittingly burnished Bodenheim's reputation and made his novel a bestseller.

This meant nothing to Bodenheim. Even as the royalties flowed in, Bodenheim attacked even favorable reviewers: "The poverty of (New York's) ash cans cannot match the pathetic debris in the heads of its literary critics." He enjoyed offensively declining invitations: Hecht recounts one such refusal, sent to a wealthy Chicago hostess: "Thank you for inviting me to dine at your house, but I prefer to dine in the Greek restaurant at Wabash Avenue and 12th St. where I will be limited to finding dead flies in my soup." Nearly everyone who ever did Bodenheim a favor made him a mortal enemy. For example, his friendship with Rascoe ended when, after learning the poet had not eaten for several days, the newspaperman gave him two dollars for lunch. The editor's failure to drop everything, take Max to lunch and pick up the tab was a grievous insult. Thereafter, Bodenheim denounced Rascoe as, among many other things, "?a literary prostitute [who, like] all the others in this gilded bordello of publishing parasites?kowtowed to nincompoops and well-known mediocrities."

In the summer of 1928, during "sixty days of flaming notoriety," as Churchill wrote, Max Bodenheim won renown as the Great Lover. He had been notorious for cutting in on a dance floor and, after enfolding some unknown girl in "a lecherous grip, and insist that she go to bed with him, pronto." Bodenheim blamed women for his misconduct, writing: "Since the dubious dawn of human history, dancing has been one of the more adroit female ruses for the sexual stimulation of the male. A young woman who embraces a man while he is being assailed by primitive drum beats and bacchanalian horn tootings, may pretend she is interested only in the technique of dancing. I wonder if the same young woman, naked in bed with a man, would insist that she is only testing out the mattress."

One suspects his genius for weaving romantic words was more effective, and though they sound silly now, they worked at the time: "Your face is an incense bowl from which a single name arises." However, like many accomplished seducers, Bodenheim didn't really like women: He merely enjoyed games of pursuit and abandonment, usually with a final savage twist of the knife.

Gladys Loeb, a dark-eyed, dark-haired 18-year-old from the Bronx, had dallied with him in early 1928. By summer, Bodenheim was bored. He told Gladys that her love poems to him were "nauseous trash." After he left her studio, Gladys clutched a picture of Max and turned on the gas. The police broke down the door in time. Waving Bodenheim's photograph, Gladys told the reporters that the poet had driven her to suicide. The resulting coverage probably inspired Virginia Drew. The 22-year-old Westsider wrote a letter to Max asking to confer about her poems and a projected novel. He replied, they telephoned, she went to his apartment on MacDougal St., and he used her.

Amidst all this, Bodenheim stayed briefly in a hotel at 119 W. 45th St.. The hotel staff later recalled Virginia Drew going up to Max's room one night at 8:00 and not coming down until 3:00 a.m.. Max later claimed she had arrived declaring her intention to kill herself, and he had spent the next seven hours dissuading her. Then he had walked her to the Times Square subway station and bade her good night.

The hotel desk clerk said Virginia had left alone. However she left the hotel, she never went home. Her father and a brother tracked Bodenheim to the hotel to find the poet not in; when Max returned, the switchboard operator told him of their visit. Max checked out the next morning. Four days later, Virginia's body was found near the East River.

The police interrogated the Drews, and Bodenheim's name was mentioned. Now even the New York Times made it a front-page story: BODENHEIM VANISHES AS GIRL TAKES LIFE. Gladys Loeb, too, had vanished. Her father somehow learned where she had gone and rushed to Provincetown, MA. He arrived outside Bodenheim's cottage with two reporters and a local constable. They knocked on the door. Bodenheim was alone. When Gladys arrived on the afternoon bus, she was intercepted by her father. Bodenheim returned to New York by train. Fearing the cops might be at Grand Central with an arrest warrant, Max changed trains at Stamford, CT, disembarked at the 125th St. station, and, true to form, went to the Rose Ballroom on 126th St., where he picked up a girl. Someone recognized him, and the cops picked him up. By then, however, the medical examiner had decided Virginia Drew was a suicide, and the poet was freed.

Yet another young woman, Aimee Cortez, had a fling with Max. Aimee loved to declare at parties that she had the most beautiful body in New York, disrobe to prove it and swing into what Churchill described as "an erotic, uninhibited dance." Aimee, too, turned on the gas while holding Max's photograph. She was less lucky than Gladys. The landlady found her dead.

Finally, Dorothy Dear, a teenager, wrote to Max. He invited her to MacDougal St. and, surprisingly, Max liked her. Dorothy was carrying his love letters in her purse in late August, 1928 when, at Times Square, her subway train derailed, its cars shattering against the tunnel walls. She died instantly, and Max's letters were found among the wreckage.

His fame soared beyond notoriety. Every major American newspaper and the European press had featured his adventures. Mencken denounced Max as "a faker and a stupid clown." Hecht later wrote that the critic's attack had placed Bodenheim beyond the pale. Bodenheim replied in his fashion: "H.L. Mencken suffers from the hallucination that he is H.L. Mencken. There is no cure for a disease of that magnitude," adding, "Mr. Mencken, who is constantly informing his readers of his libations, is a total fraud. He drinks beer, a habit no more bacchanalian than taking enemas." Nonetheless, Bodenheim became "more ignored than any literary talent of his time."

More importantly, Max stopped writing the novels that had proven so lucrative. As the Depression deepened, his royalty checks vanished. Emily Paley, whose mother owned Three Steps Down, a cafeteria on W. 8th St., told Kisseloff that her mother always fed Max Bodenheim although he had no money, saying, "Just keep a little book of what you owe us." Even in his good years, he arrived at parties with a burlap sack into which he loaded all the liquor bottles and canapes possible before being thrown into the street. He drank at Village bars such as the San Remo, swilling gin from a water glass. Once the bars closed, he would move to the Waldorf Cafeteria, on 6th Ave., which resembled "an enormous bathroom bathed in sickly yellow-green light," and sit for hours over a single drink or cup of coffee.

In 1935, he began working for the Federal Writers Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a New Deal emergency employment agency. Bodenheim worked on projects such as the guidebooks New York Panorama and New York City Guide. After the WPA's arts projects were curtailed during WWII, Bodenheim became a homeless wino, scribbling doggerel on scraps of paper to sell for drinks. Some magazine editor occasionally bought a poem for $25 or so.

By the early 50s, the "tall, cadaverous, unwashed" Bodenheim spent much of his time drinking straight grain alcohol. Hecht wrote that, after awakening at Bellevue from a two-day coma after being picked unconscious out of a Bleecker St. gutter, Bodenheim explained, "I must have had a drop too much." After one of Bodenheim's visits to Hecht's house in Nyack, Hecht realized Max had ransacked his closets, stealing socks, shorts, ties, shirts, pajamas and a pair of shoes. He responded by retaining Max for $35 a week to send him a poem or two pages of prose.

His last affair began one rainy night in Washington Square when Bodenheim met Ruth Fagin. The 29-year-old later explained, "He had an umbrella, and I did not." They married, and she thereafter seldom left his side. They occasionally slept in rented rooms or flophouses, more often in subways or doorways or on park benches. Occasionally, Bodenheim beat her and, after knocking her down, kicked her in the head.

In the fall of 1953, they met Harold Weinberg, a dishwasher with a history of psychosis and petty crime. The night of February 6, 1954 was bitterly cold. Weinberg had a room on lower Third Ave., just above the Bowery. The Bodenheims went there. Weinberg shared his whiskey, and then Weinberg began making love to Ruth. Bodenheim rose to his feet. Weinberg drew a pistol and shot the poet in the chest. - www.nypress.com/village-rogue-the-poetic-life-of-maxwell-bodenheim/

Most of Bodenheim’s works of fiction center around the theme of rebellion against authority. He reportedly uses an unusual amount of imagery in his writing, which critics view as highly individualistic. The protagonists in Bodenheim’s works are often confident youths who reject parental authority, a central theme of Bodenheim’s work. His female protagonists reject society and express this rejection through sexual rebellion. - more here

On the night of February 6, 1954, in the lower intestines of Manhattan, two homeless people, an aging, booze-addled poet and his young, unstable wife, sought shelter from an impending late winter storm. The idea of yet another night spent sleeping on park benches–no matter how swaddled with alcohol and newspapers the two might have been–was too painful to bear.

Then the pair crossed paths with an off-duty dishwasher, with whom they were acquainted from the bars of the Village. The dishwasher had the hots for the old poet's wife–who did little to discourage his interest–and offered to share his room on the fifth floor at 97 Third Avenue with them. Numb from cold and booze, the trio managed, with their suitcases, bottles of wine and other potables, to make it to the dingy walk-up flat. The old poet was offered the bed, a glorified cot, where he flopped, pulled out a book and commenced reading. He seemed as at home here on this strange, fetid mattress as anywhere else in the world.

The young wife and dishwasher continued drinking. Soon enough, they began groping on the floor, then rutting like demented goats not more than an arm's length from the cot on which the old poet was thought to be sleeping. But the old poet had noticed their state of arousal and challenged the dishwasher. Much younger and stronger, he overpowered the old man and shot him twice in the chest (appropriately, right in the heart). The old poet died instantly. With his young wife screaming bloody murder, the dishwasher plunged a hunting knife into her back four times. After a struggle she also died, her body grotesquely twisted in her final agonized moments on the floor. As the killer left the blood-drenched, completely ransacked room, he locked the door from the outside.

The cops didn't come until the next afternoon, when the rooming house proprietor asked them to break the padlock because he was owed back rent (apparently the sound of a struggle and a gun going off twice didn't attract curiosity from the other tenants). On a table near the bed, the cops found some scribbled poems, a pad of paper and pen and an empty liquor bottle. Propped up against the table was a hand-lettered sign that said "I Am Blind," which Bodenheim was said to use to beg for money on the streets. When the identity of the poet was discovered and released to the press, the details of the crime dominated New York newspapers for days. The killer was easily apprehended soon thereafter; he confessed to the crime but was deemed mentally incompetent to stand trial.

The murder was the final, seemingly inevitable chapter in the life of one of New York's literary legends, the author of 10 books of verse and 13 novels, as well as a partly ghost-written memoir called My Life and Loves in Greenwich Village. The old poet's name was Maxwell Bodenheim, age 62; he had once been king of the Greenwich Village bohemians. Bodenheim's 35-year-old "wife"–it was never clear whether they were legally married–possessed the Dickensian name Ruth Fagin (alternately spelled in the papers as "Fagan" or "Fagen").

The 25-year-old killer was officially named Harold Weinberg, although he was known around the Village as "Charlie." Described by Life magazine as "a wild-talking, scar-faced vagabond," the truth was that he may have been mildly retarded, even schizophrenic and that he was tolerated by the legendarily non-judgmental Villagers who saw him around the neighborhood. The murders gave him a sudden, perverse fame, and he basked in it, describing the grisly events of February 6 to the police and scandal sheets–just as they’re recounted here. In lieu of facing the two murder charges, Weinberg, aka "Charlie," was sent to a mental institution.

* * *

In the 1920s, when Greenwich Village was in full flower, Maxwell Bodenheim was known, even to unhip middle Americans, as the living embodiment of bohemian existence. He'd inherited the mantle from the late John Reed who, before he became the playboy-revolutionary depicted in the film Reds, was the "golden boy" of Greenwich Village. Indeed, Reed's poem The Day in Bohemia, or Life Among the Artists (1912) was perhaps the first open declaration that America had its own thriving "Left Bank."Reed, a Harvard graduate so prodigiously gifted that his renowned mentor, Lincoln Steffens, told him "you can do anything," chose the carefree life of the artist and applied his writing talents to documenting it. His verse, a mirror image of his own jeu d'esprit, echoed Joycean wordplay and presaged early Beat poetry, with everything from guttersnipes to high society names, faces, bars, bistros, people, streets, bookshops, stray chat, shouting matches, howls, moans, shouts of glee: "Inglorious Miltons by the score,/ Mute Wagners, Rembrandts, ten or more/ And Rodins, one to every floor./ In short, those unknown men of genius who dwell in third-floor rears gangrenous,/ Reft of their rightful heritage/ By a commercial soulless age./ Unwept, I might add, and unsung, / Insolvent, but entirely young." The poem went on in this manner for thirty-five pages.

When Reed died in Moscow in 1920, Max Bodenheim, who had just moved to New York, willingly picked up Reed's banner. A prolific poet, novelist, provocateur and performer, as well as an inveterate womanizer, the handsome and self-promoting Bodenheim was known to millions for his willful embrace of all things unconventional. "He personified the avant-garde," wrote Life. "He was young and slim with sandy red hair and pale, baleful blue eyes, and women jammed tiny candlelit rooms in the Village when he gave readings of his poems."

His personal history was shrouded by sometimes-artful mystery. Bodenheim–known as "Bogie" or Max to friends–variously identified his birthplace as Mississippi, Missouri or Illinois and his birthdate as 1893 and 1895. (The truth is that he was born in Hermanville, Mississippi on May 26, 1892.) His family moved to Chicago in 1900, and when he told his shopkeeper father that he wanted to be a poet, the idea did not sit well. They quarreled, and the enmity increased when Max was expelled from high school. The prodigal son left home to hop freight trains in the Southwest (or so he claimed), but soon joined the U.S. Army. He was in the Army from 1910 to 1913 but was dishonorably discharged after a stint in the Fort Leavenworth brig for going AWOL and–so again he claimed–for bashing an anti-Semitic officer over the head with a musket.

Upon his release from prison, Max drifted back to Chicago with a suitcase full of poems, rejection slips and a bottle of Tabasco sauce. While his self-created myth was that he was an outcast living totally on his wits, Max actually moved back in with his mother and father. This aspect of his life, hidden from his Chicago literary comrades, was later revealed in his 1923 novel Blackguard. This was a thinly veiled autobiographical account of the prodigal son's inauspicious return to face his mother, embittered for having fallen from her social station, and his father, embittered over failed business ventures. Even with a roof over his head and free board, Max still found much to alienate him in the city, describing his family's apartment as "standing like a factory box awaiting shipment, but never called for."

more here

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.