Iphgenia Baal, Merced Es Benz, Book Works, 2017.

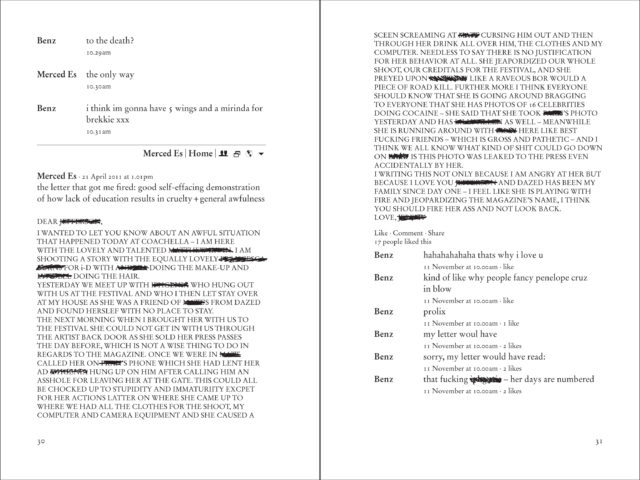

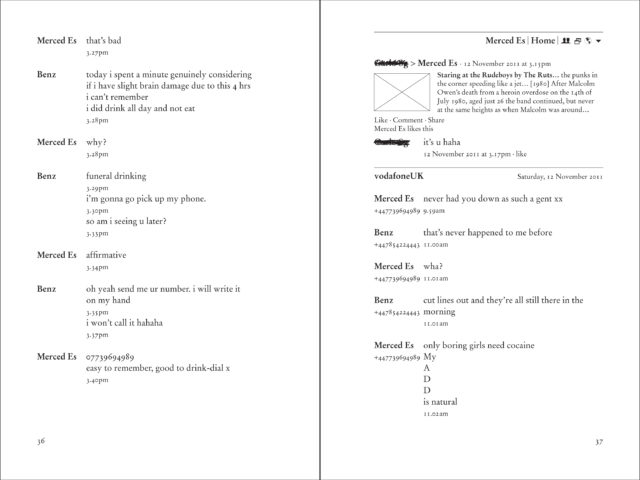

Merced Es Benz is an account of a dysfunctional love affair, narrated via SMS, email, Facebook and Google search results. Events unfold against a backdrop of a barely-credible pre-Olympic London where Bow E3’s high-rises are no longer the Ends and east London’s awful art parties, populated by the debased progeny of the rich and famous, do little to dispel 90s rave nostalgia. Remnants of a ‘virtual’ conversation act as a body of circumstantial evidence, betraying a ‘real’ intimacy behind a messy social media scandal that spilled into tabloid coverage.

Iphgenia Baal’s non-fiction novel balances at the jarring intersection of death, mourning and Facebook, as downward mobility proves to be a more intoxicating – if less fatal – drug than heroin. It is published as part of the Semina series, commissioned and edited by Stewart Home, that also featured books by Bridget Penney, Jarett Kobek, Katrina Palmer, Jana Leo and Mark Waugh, as well as Stewart Home himself. Merced Es (10 November 2011 at 11.03pm)

whenever i write things on facefuck, i can always imagine them being read out at a later date in court...

Benz (11 November 2011 at 8.40am) · Like

all these little things - trust me

From a shared can of beer in the twilight of London rave culture to a tragedy at a corporate rave in gentrified Shoreditch years later, Iphgenia Baal’s third book, Merced Es Benz narrates the arc of a doomed relationship. For anyone who found love in an online chat window or was tantalized by the possibilities of its ecstatic immediacy during the early days of social media, the format will undoubtedly be familiar. Pieced together from fragmented Facebook conversations, the novel published by Book Works in March 2017 is an epistolary novel that relies on the ephemeral messages sent from parties, buses and bedrooms to reconstruct hazy personal histories. Punctuated by distance, silence and cruel romantic games, Merced Es Benz ultimately shows the fragility of our online lives, and the difficulty in making sense of our entanglements through the scraps of ourselves we leave behind on the web.

It’s significant then that Iphgenia and I speak over Skype, followed by more emails and collaborative edits. The first conversation gets off to a glitchy start, while I struggle to get the camera on my laptop working and set up the recording. “Sometimes it’s better just to use a tape recorder,” Baal suggests jokingly before everything finally gets going. It’s late afternoon in London, and the darkness is creeping into her apartment, a stark contrast from the lazy Saturday morning sunshine in Los Angeles. In our hour-long call, it becomes clear that the author possesses an unshakeable DIY attitude, and a commitment to approaching her literature — and her life — without compromise.

Set against a wealthy London clique who dominate the art, music and real estate scenes, Merced Es Benz gives an intimate insight into a floundering relationship that is collapsing under the pressures of drug addiction, shady secrets, misleading online personas, and the slipperiness of online communication. As the two protagonists flit across London and the world, falling in and out of sync with each other, ultimately the struggle to keep up with a privileged party crew reaches its inevitable conclusion.Perhaps most importantly of all, in a world where heroin dependence is a minor medical issue for the rich, but a moral failing for the rest, the book works to preserve the legacy of a relationship that has been corrupted by the clichés and judgments that inevitably accompany addiction. Emerging from the midst of London’s flagging alternative culture, Merced Es Benz embraces the possibility of love no matter what the cost, and grapples with the consequences of refusing to conform.

Like Baal’s previous work, there is a visual element to the writing process, with other media forms incorporated into the design of the book. This strange copy-paste technique, full of redactions, phone numbers and timestamps, gives an urgency to the events that would be lost with a more traditional approach, and gives additional weight to what goes unsaid.

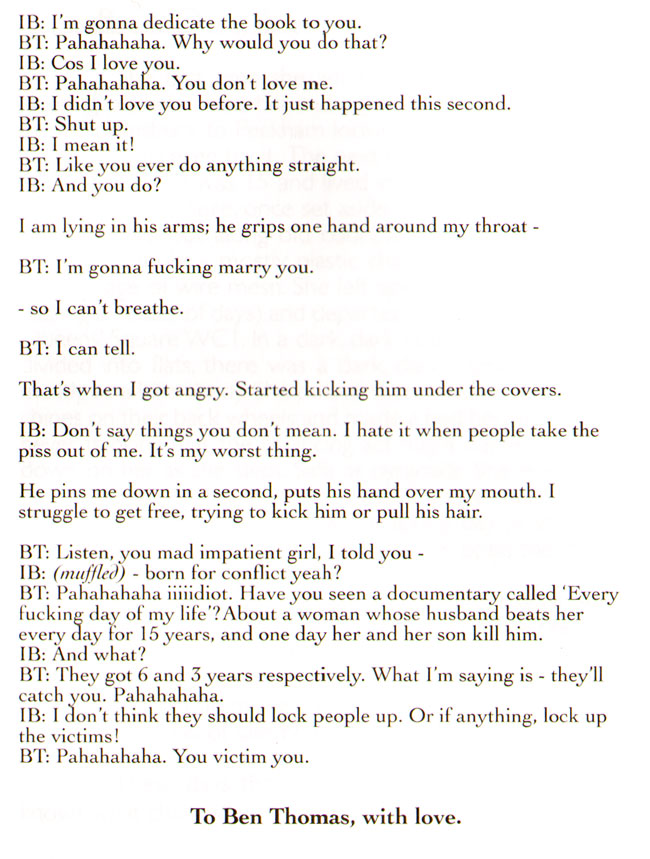

** How much of your relationship with BT in Merced Es Benz is fictionalized?

Iphgenia Baal: It’s all fiction, insofar as the act of writing something down requires omitting 99 per cent of reality in order for it make sense, but since a lot of the relationship was written in the first place — we spoke as much over Facebook and in texts as we did face to face, so the ‘fiction’ was built in. It wasn’t two people talking, it was two personas interacting, a phenomenon exaggerated (if not caused entirely by) Internet and telephones. The conversations [included in the book] are like clues, evidence of real people and real events, but who the people are and what actually happened remains unclear.

** Was it tough to go back and revisit some of the experiences you chose to include?

IB: Not really. I mean, the first messages I read after [BT] died were the ones we’d sent on facefuck, mainly because the conversations didn’t take much finding, they were just there. The first conversations I read were some of the last conversations we’d had, mostly empty threats and desperate sounding messages. Reading those made me cringe, but months later I found a load of texts on an old Blackberry and when I read those, I didn’t recognise myself at all. I suppose I approached them in the same way a very nosey stranger would. And what I found, or maybe constructed, was this spooky subtext—pretty death-obsessed. Also, the constant miscommunication: messages sent without previous messages being read properly or at all… plus the lazy assumptions people make. Like, if you post a picture of yourself at the beach, everyone assumes you’re at the beach, when you could be anywhere. Things like that can be a mistake, or done on purpose, but in the end have the same effect. I mean, maybe it’s a trite example, but when you add it all up, it totals a deluge of misinformation… why our communication these days is so frayed and basically fucked.

** The first line in Merced Ez Benz reads, “Whenever I write things on Facefuck, I can always imagine them being read out at a later date in court…” Can you talk a little bit about that?

IB: It was, amusingly, the first interaction Merced Es and Benz had online. Other than that, the sentence works as a pretty smart modernisation of the old ‘publish and be damned.’ So, it’s a disclaimer. The idea that simply stating an idea is enough to offend people has always tickled me, but then what with all the online shenanigans these days, the ‘burn the witch’ mood in society is heightened to a tiresome degree. People love a lynch mob, which is in fact what I was writing about in The Hardy Tree—A Story about Gang Mentality. It’s not the gang mentality people assume—drugs and dealers and guns and stuff. More people grouping together, towing the line…

** In Merced Es Benz and The Hardy Tree the climax occurs at a rave. Did you grow up in rave culture?

IB: I went to squat parties when I was a kid but, as people never tire of telling me, I’m too young to really remember rave culture. It belongs to the generation before mine, so all the free-party-living-in-a-trailer-M25, blah blah blah, was ultra-mythologized for my lot, because it was the thing we’d missed. But look at London now—that whole culture is dead. It’s been suppressed completely. Not just squat parties, but the whole mentality of feeling like you owned your city. Only yesterday I got fooled into going to a bar in Dalston and as soon as I walked in I thought, ‘What the hell is going on?’ It’s so boring. The music is shit, the music is quiet, the décor is bad, the drinks are expensive and everyone’s dressed up. I dunno, I looked around and just thought, ‘you lot have no fucking idea…’

I only realised recently that The Hardy Tree and Merced Es Benz not only have the same sort of structure, but also conclude in the same sort of way and I think it’s just because, for me, raves were always the most romantic, they were where stuff happened. And now, no more, so yeah—lighter in the air at an emo gig—RIP the rave. Goodbye.

** What are your thoughts on ‘counterculture’? Does it exist anymore?

IB: The current consensus seems to be that counterculture is dead. I mean, I’ve heard it enough times, but I think there are always going to be too many people to catalogue who aren’t willing to do what they’re told, but I think these days it’s more difficult to find evidence of them. Maybe one aspect of today’s counterculture is that it wants to be incognito, in protest at the rest of culture’s constant thrust to promote.

** I’m interested in the format of this book. There have been a few books lately that pursue an epistolary style that use email or text message, but yours is one of few that I know of that derives its material from Facebook.

IB: I think a lot of the reason why people don’t admit to using Facebook or don’t use it as content is because it’s lame. Also, it’s a more recognisable brand than email or text, even if these are also delivered by specific carriers, but for some reason it’s less immediately obvious.

** Your books tend to include a lot of visual elements. There’s a piece online, one where you’ve written inside a phone bill. Or in The Hardy Tree, which pieces together the story of Thomas Hardy’s ‘Resurrection Men’ who cleared gravestones in St. Pancras to make way for the railway with newspaper cuttings, handwritten letters and other documents…

IB: The Hardy Tree is the only book I wrote in Word, because it was before I learnt InDesign, which has now become what I write in. I used to write in-house for a magazine and found the best way to edit text was by giving it to the design department, who’d say, it needs it to be five lines longer or three lines shorter and I’d hack at it accordingly. It made me less precious about what I’d written. Like, if something’s got to go, it’s got to go. Plus, I like having different processes. If I just write, I go mad and design without content is dull.

I guess I’m begrudgingly learning to be more professional—I’ve always been decidedly anti-professional and highly suspicious of professionalism, mainly because I remember reading books when I was younger and thinking, ‘How could I ever do that?’ But what I later came to realize was that this idea of the ‘great author,’ the ‘exceptional individual,’ is a myth. Almost all cultural produce, books included, goes through countless stages of editing and making, usually by multiple people. Weirdly, I think it is in these stages where the cost or worth of a book is defined, rather the actual writing. The creative… or the entertainment industries, whatever you want to call them, professionals seem to radiate a sentiment of ‘We are the ones who know what we’re doing, you’re a moron, so buy the book and shut the fuck up.’ So, I’ve always liked the idea of being unprofessional as in opposition to that, but I suppose in the end, being professional is just knowing what you’re doing, which sometimes means knowing that the right thing to do is to let someone else do it.

** Do you think people’s accessibility to other people’s thoughts and rants on social media has made this fragmentary style of writing more acceptable when packaged?

IB: I can’t speak for anybody else, but I love bad writing as much as I love the rants of lunatics. Most people accept whatever, as long as it is presented in the right context. The wrong context, or confusing them, can provoke all sorts of reactions, but mostly being totally ignored. Course this can be played with. People have certain expectations of books, the same way people have certain expectations of screens—but imagine trying to make someone log into your Facebook and force them to scroll back for months and then read all your boring shit… I mean, it’s not gonna happen, but in a way that’s all Merced Es Benz is.

**[Spoiler] In the first chapter of Merced Es Benz, BT has died basically, but then you lead with a conversation between the two of you. There are these long gaps where he doesn’t respond. It’s almost like he has already died in a way. You just keep talking and there’s no response.

IB: BT wanted to be wanted and he was very aware that not responding to people was an effective tactic, but Merced Es Benz is a dual narrative. His narrative might seem the dominant one—a story about this crazy, crazy guy, clever, amazing, fucking lunatic bastard on a death trip, but the other part, the female narrative is not some meek, long-suffering… she’s a menace. I guess I was trying to out myself. I mean, it sounds stupid, but after BT died I briefly entertained the idea that I’d texted him to death. But no, at its core, whatever else is going on, it is two people who refuse to do what they’re told—maybe a decent example of the sort of counterculture I was talking about earlier. People who won’t accept what’s given to them and who’ll break even useful rules on principle.

** Jumping to the end of the book, explain the tabloid material.

IB: The first draft of Merced Es Benz was an edited version of a series of private conversations without explanation, but as the idea of publishing the text became more real and I started to think about how to make it not only make sense to someone else, but to mean something to someone else—death is cheap in fiction, the inclusion of the hack journalism worked as shorthand for the shitty state of culture.

Summing up [BT’s] life as ‘Mick Jagger’s son’s friend’ is so crass. But I mean fuck, it’s not like BT is the only victim of this shit. I mean, the Rolling Stones have quite a trail of dead bodies in their wake. I’m not laying the blame for anything at anyone’s feet. I mean, everyone’s a victim of this shit, even the ones who are doing it, and yeah, ‘sympathy for the devil,’ but no actually, he’s a cunt—and Jerry Hall married Rupert Murdoch. What more do you need to know? No one can help who or what they’re born to, but they can help what they do with it. Which is always jack shit—I mean bless them, but no, I don’t need Rupert Murdoch’s stepson telling me to ‘save the oceans’. It’s like, ‘Fuck you, fuck off.’ This is why I don’t get invited to weddings, I just want to egg Rupert.** - Matthew O'Shannessy

Iphgenia Baal, Death & Facebook, We Heard You Like Books, 2018.

No one wants to end up #RIP with 45 likes, your death traded as someone else's fleeting social capital, your last inane status update being the one that defines you for all time, your 'Friends' competitive grieving, and misery tourists perusing your profile.

But Facebook has become the channel for broadcasting news of the recently deceased, with the number of "memorialized" Facebook accounts soon to eclipse accounts of the living. Mark Zuckerberg is a merchant of death.

Whether it's the demise of another geriatric celebrity, or that your best friend from college took a pill and jumped off a roof, nothing makes your News Feed blow up like someone being dead. There is a rush to tag the deceased in albums of lo-res photos, to share favorite songs as YouTube links, and to post long, dolorous, largely misspelled status updates.

Facebook claims the deceased as its own, commodifying misery and entering it into its usual agenda: stalking your online shopping habits, advertising clothes, confused political declarations, and wondering why you haven't had a baby yet.

Set in a London where Mick Jagger's kids rule the social scene, Death and Facebook is a true account of a dysfunctional love affair that ends in disaster, posthumously pieced together from threads in Facebook Messenger, archived email, saved SMS, and a Google search history.

Cliqued by proxy into Dodie Bellamy’s (born to sneer dismissively about the flank of her Buddhist sebum & riding some long expired mid-west working class cred) most fleeting and be-caped endowments (paper towel wipe of political-writer-arrogance-cum-mundane-new-narrative-diary-graph endemic to San Fran), iphgenia baal (the pronunciation of which is its own insufferable reparation / too patriarchal if capitalized / character white guilts yuppie pals into buying her drinks / prime to move copies with another super-ethical, f-the-corporation (ballsy maybe twenty years ago), slogan-wrought (SJW PP time) NPR chum trending its propagandistic new left media Iago ballyhoo (titling the hydra-dependent soapbox as it cousins her protests) inveigles readers (even one this mean and pasty) with the tale at hand, because attention, lost and gained (unto aforementioned death), is her book’s motif. Enchanting splotches tobogganed down daddy’s comforter (she’s not yet another victim in a half shell), the spanked array of politics and ass may be capable of rooting up an eye or two while a sophisticated talent endures below ideology (getting under the skin it aroused and bleeding the life out). It’s art, though, not a marriage, and for zero to five likes online, I’m willing to call baal an artist. Any click-count higher and I will correct my mistake and revert to the previous hatred. Her publisher (Jarett Kobek, to whom I apologize) wrote a brilliant book (Atta) that, to the shame of our anti-literate country, relatively few people bought. He then changed his approach and wrote a gimmicky (overtly) political conundrum (sneaking talent in) and profited, if any lit could provide the ink for a receipt (thumbs up and hearts from me, he awesomely Trojan horsed the culture).

Wage gap dilly dally or not (be I goober-level republican-menaced (which libel will knight me a Nazi for decamping from PC church) by inclusivity (however insincere) even having no position rich white guilt can finagle from me? – right wingers almost had countercultural heft for the first time in this safety scissors internet, but, of course, dropped the ball forthwith), baal’s lineage perjuriously discriminates from ipseity to rave, alt lit to shoehorned new narrative to civic spillover (not her fault, tis my psychotic fault: I see all current art tainted as such). On the other bland, certain strains of cosmopolitan undergrads gotta suck the sickle ‘cause it’s the furthest taboo megacorp paradigm. You couldn’t accuse the prose’s complete, if intentional, egalitarian lack of style (no decadent elitist aesthetics to distinguish individual vision above the official commonality (or satire of such?) – we live auto-mocked in our own sincere parodies) of an amateurishness fobbed off by somebody not ready to be published yet, because everyone writes plain now, and the point is online relatability. A lot of writers preemptively and defensively mistake hard-spun daily travails for bravery and show as much by treating any creative torque, any weighted line, like ostriches hiding in the sky. There are very few youths I relate to (with their clothes on), for a million self-puckering reasons, not just because most have been raised to be proud snitches (re baal’s delightfully bonkers, hottest of the nightmare lays, feminist PMS threats to shop some drug dealer casualty bro she got bored humping to the rozzers (bro is the weak American slur her brand prefers (though I like how sneakily off brand she ends up). We’re post scandals-that-require-an-actual-crime (concerning people with a millimeter of power or attention). Attention across platforms has become its own slithering context and we, target market, inhale the docious wet wipe. Anyway, a supermodel in a slightly less moneyed situation than the well-to-do partiers that surround her runs afoul of an edgier dope mule, then sticks us with the transcript for masturbation material (we are grateful). As the production company’s boiler plate seems to be to phantom thread us a little literature under the guise of accessibility, baal does work a scratch and sniff cemetery below the medium. I apologize for demanding a denser population from its sepulcher.

If you disdain communities (which, pardon, was once an artist’s goddamn thing – left / right / center: incinerate them ambidextrously), why not burn one down from the inside (London via San Francisco), with their own festering style, and reverse that vain society into art, because I don’t care about you or your stupid friend drama (flip Capote how he likes: that’s not writing, that’s social studies; good journalists flunk the beret) or why their names are being obscured into Russel Edson nouns or handed to me out of nowhere on a cute tray with zero exposition (don’t make me crave exposition, you’re the authoritarian square here, oppressed or not): stop journaling at me. I suppose I should join the mutual frig, included in and occluding on insert-author-name’s privacy (authors equaling the undertow of a national work front or group product regardless of intention), but baal veers smartly from this approach into a conceptual meltdown. She’s not your common protester for likes. She’s produced the best kind of degeneracy, mirroring the façade outdoors, forfeiting a malleably purchasable beauty and a fake, well-sponsored system-daddy revolt to spike her pathology across a piece of epistolary carrion.

Remember when the literary troupe trotted out the word “body” as some kind of critical whatsit because they all donned a classroom chicken suit? Foisting cowardly comments with pretentious handles of anonymity – like thirteen year old sexpot Lonely Christopher, for instance, a living being, I’m to understand (imagine Adam Scott with typhus, trying to look hard and experiencing the bends), who holds open forums across the social hemisphere as if he’s judging wine bottle insertion on American Idol, administering justices hither and tither with the dumb, barely-lingual conceitedness of an adiabatic politician, a real throwback to when scarfing too many dick-murdering pills was just for the moneyed – one short film featuring Julian Richings’s amazing mug is the closest this authorite ever came to a produced style (writes like a dog dug a chewing gum-sized hole in his (zis? xis? cherwivis? xxxlonely fizz? writer1110101012994?) professionally-lit headshot and vomited MDMA (that might be an improvement – more like toned but generic, traditional New Yorker stories, if their content was allowed to yawn ten percent less; as daringly homosexual as James Franco, a venereal rubric, a congressional yarn). Are we undoing language (L plus A plus ad infinitum) theory-head poetry back to plain-head New York School (the training wheels of simplicity, the presence of the poem, its presence!), back to Black Mountain School (before the beats, who at least wrote lyrically, were stripped of their poesy and the remaining politics were knighted into (again) new narrative – generations later the post-alt babies of Tao Lin really hate their dad because he’s better at their “style” (and lives!) than they are), back to Imagism, back to a faux-deep, concrete glyph disrupting William Carlos Williams’s eleemosynary day job, the breed kennel of Americana fast food verse, hack muckraking 101 (guest appearance from G. Stein speed-bagging my nutsack into the rhetorical loop it already was), all the way back to Fanny Burney (everyone today is her), pegged by under-read madman John Davidson as possessing the originality of ignorance, Burney’s frank tales reading like trained meat for profit?

I hope someone shoots the wings off my every concession. This book (death & facebook) is a fetish gone wrong by someone who might deserve their genitals (time will tell). A rare treat nowadays. At least this cool kid party transcript has a body count. The culmination seems to funnel the window-shopped death therein so the narrator can stroke her immaculate person. Death on an abstract grid, caskets wagging through the air for group approval – skip straight to the throes, the rattle, the lubed whisperings. That the dipshit who got lucky with her is a corpse may be the best part. If those eyes weren’t turned to goo, if he could even read in the first goddamn place, worms would twerk the dust deeper into his sinuses until they came themselves in half. - Sean Kilpatrick

Iphgenia Baal lives in London, England. She is the author of three books, the most recent, Death & Facebook, was published in July by We Heard You Like Books. Death & Facebook memorializes the sometimes turbulent relationship she had with a boyfriend who died of a drug overdose. Across devices and social networks, their online exchanges propel the narrative. Death & Facebook makes you consider all the e-artifacts left behind to speak for you when you die. For a book about missed connections and the tragedy of dying young, it’s a lot of fun, with truncated critiques of rave culture, wealth and celebrity. (I kept thinking of Tama Jankowitz. Iphgenia probably won’t like that.) Iphgenia was a writer for Dazed and the end of her time at the magazine is chronicled in Death & Facebook.

Iphgenia and I hung out in New York City last year. She is the kind of person who can turn an everyday occurrence into an unexpected adventure. I watched her hide one of her books on a shelf in the Rare Book Room at The Strand and thought to myself, “What an ingenious idea,” but didn’t have any of my books with me to hide. We also took a morning stroll to David Wojnarowicz and Peter Hujar’s old apartment on 2nd Ave. I talked to Iphgenia over Skype while she was visiting Los Angeles. This interview has been edited.

FIONA: Are you liking L.A? Did you have any exposure to it before this visit?

IPHGENIA: I’ve been here twice before. The first time was years ago, which was a complete disaster. I was with all these awful fashion people and it was just really confusing. The first night I arrived I was taken to like a Swatch party at Britney Spears’s house and it just didn’t make any sense. She wasn’t even there, which was annoying. It was just loads of like watches on plinths, backlit. Stupid.

Was this while you were writing for Dazed ?

Yes. They hired me when I was 20-21, and I liked it for ages, but then very quickly I started to hate it. After that, it ended pretty fast.

In Death & Facebook there is a redacted email from one of your co-workers at Dazed that explains how things ended for you there—why you were fired. There was something that happened backstage at Coachella?

Yeah. It actually doesn’t really tie in to the rest of what Death & Facebook is about, but the letter’s so good, I thought I had to get it in print. It’s hilarious.

So, did you really threaten to leak pictures of Lily Allen doing coke?

No. I wish I did. Are you familiar with the guy who wrote the email? His name is Jeremy Scott.

No, but I recognized the name of one of the photographers you mention working with at Dazed.

Matt [Irwin]?

Yes. He killed himself!

He did kill himself.

That sounds so crass, but I remember his photographs of celebrities, and you keep suicides in your memory more than other deaths. At least I do.

Him dying was a weird one. It was years after my working relationship with him at Dazed ended. I got fired in 2009, I think. I’d been there for six years, but Matt had only been there a couple of months, but he really befriended me. Then, when we were in Los Angeles, he turned on me completely. Like he had a split personality. Really vengeful and insane. It didn’t make sense at the time, but when I found out he’d killed himself, it, I don’t know, made sense? He had crazy Christian parents, who I think disowned him when he came out of the closet, and from thereon, it sounds like everything was pretty fucked up.

He was a good photographer.

He was. But I think part of the problem was his work. I mean, he had his own style, which he basically abandoned for ultra-cutesy, pop pics of Harry Styles. I don’t have a problem with that stuff, and it works for fashion, but I think if you aren’t a moron, then that kind of thing in the end, just drives you crazy. So yea, when I found it he was dead, it seemed kind of obvious. He wrote his will on ‘stickies’.

Sticky notes? That makes it sound like his death was very spur of the moment.

I think he was just very out of touch with reality. He was so Instagram that it never occurred to him that ‘stickies’ wasn’t a legally binding medium.

I like that expression, “so Instagram.” When you wrote for Dazed did you see much behind the scenes brokenness?

I guess so, but what I really saw was a bunch of ageing geeks trying to maintain their relevance. It wasn’t a very glamorous place. Just a warehouse filled with people on less than minimum wage, who had to suck up to total dickheads for their wages. Then again, I must’ve liked it a bit at some point, because I was there for a long time.

You did an interesting interview with Poly Styrene of X-Ray Spex before she died.

She was great. But she tried to sue me. That was sort of the beginning of my downfall at Dazed. I went to interview her about her punk rock days, it was supposed to be ‘looking back’, but she’d turned into a massive hippy and wasn’t interested in X-Ray Spex, which I thought was fair enough, so we talked about whatever, and when I wrote the article, I just made the whole thing up. That was the sort of journalist I was. Anyway, she had a brother who was a Nation of Islam lawyer and she called me up and told me she would sue me. But then she died. I felt awful. But also I didn’t. I mean, who cares? It’s not like Dazed is exactly a verifiable source of information. I didn’t take offense. But it’s weird, because years later, Dazed put the article up on their website. I think it’s the only thing up on it by me, so maybe they don’t remember being threatened with legal action. Or maybe they just don’t care.

Death & Facebook is about the relationship you had with a boyfriend who died of a heroin overdose. The text of the book is made up of your virtual interactions: your Facebook comments, emails and text messages to each other. I don’t want my questions to come across as crass or cold. Your boyfriend’s death, which opens the book, is very sad, but your interactions, as they’re happening across all these different social mediums, are very funny. There’s a real joy to reading the text. It’s not at all heavy or somber, even though we know from the beginning of the book that he dies. In the first chapter, you’re out at a party and your phone starts ringing, and people approach you and tell you that he’s died. There are a few girls at the party who are also reacting to his death, and they’re saying things like, “He was my best friend!” and “My best friend just died!” I’ve had friends die, and I’ve noticed this phenomenon where people try to lay claim to the dead person, to what there relationship was, almost competitively. You see it online to an extent when a celebrity dies. People either expound on or embellish their connection to the person. It becomes like a performance. Did you feel like you experienced this with your boyfriend’s death?

The weekend he died, which makes up the start of the book, was very like that. Everyone competitive as to who knew him best, or who saw him last. I felt especially weird because my relationship with him was over. We hadn’t spoken in a couple of months. This guy who I kind of loved, but now hated me, was dead so, what do I do? What’s funny is that everyone laying claim to him after he was dead disgusted me, but later I realized that the book is, in a way, the ultimate laying claim to someone. First, I wouldn’t have able to write it if he wasn’t dead. But also, because most of what people other people said was spoken, in the pub, at parties, but mine was in print. And in print means forever. Or as good as.

You use web links in the book to illustrate things that aren’t necessarily spelled out in the text. There’s a link that shows how your boyfriend’s death was covered by the British media. He was good friends with the sons’ of Ron Wood and Mick Jagger. How did it feel seeing him represented in the media that way? As the deceased friend of famous people’s children? His death was used by British tabloids to write salacious stories on the children of rock stars.

It was depressing. I mean, what a way to sum up someone’s life. It’s really grim. But I think the saddest thing about it, is that the all those rock star kids are as much a victim of it as the people who aren’t and just read it in the paper. They were actually his friends, and I don’t think they’d want him remembered as ‘someone famous’s son’s friend’ either.

How much editing did you end up doing to the book? How did you choose what online interactions to include? Did you have a narrative in mind?

I only decided to write something about it, a long time after the event, so initially, I chose what to include just by what I could find, and trying to make sense out of conversations that jumped from one medium to another. Like from Facebook to phone. I left out a few conversations which implied other people who were still alive’s criminality. Also, stuff that just didn’t make sense. I added things like conversations we had in reality or over the phone, and wrote them out as text messages. I did find an old Blackberry, which had a lot of messages from the start of the two of us hanging out. But basically, I tried to piece together everything I had with everything I thought, felt, and remembered and then make it make sense. To me, as much as to anyone else.

I thought that that was a really smart device: you don’t say that he was definitely involved in drug smuggling, you just sort of imply it, through google search links about drug smuggling.

I think it works, mainly because most of the time when someone is up to ‘no good’, no one ever comes out and tells you or says it, there is just a general sense that something’s going on. You suspect. It’s like watching someone try and keep control of a situation, who’s already out of control.

There’s a lot of travel in the book. You go to Africa, your boyfriend goes to Ethiopia, and then he goes to Thailand.

When I think back to that time, it felt like he was this guy who had money and could do what he wanted and I was just sitting around in a council flat wishing I had a life. But when I looked back, I realized I travelled quite a lot. I think it’s one of those things, if you are brought up thinking you can go places and do what you want, that is essentially wealth. More than money. The idea that you are allowed, whether or not you can afford it. This also applies to writing, the idea that it is allowed.

Your two other books Gentle Art and The Hardy Tree are fiction. You play with the font and size of the text, and break up sections in Gentle Art with images that say things like “WANK FANTASIES HAVE FEELINGS TOO.” Is Death & Facebook your most autobiographical work? Would you have written Death & Facebook in a regularly structured format?

Death & Facebook was the first book I’ve done that is ‘real’, as in it’s about real people doing real things. I redacted a lot of names, but people can recognize themselves. Just before it came out, I got really paranoid that people in it would freak out, but instead there’s been a vacuum of response. The conclusion I come to, was that the sort of people I am writing about don’t read. All your work that I’ve read is about ‘real’ people. Do you ever worry about people getting pissed off?

I had a boyfriend tell me blatantly, ‘I don’t want you to write about me’. He also made a concerted effort to try to change the way that I wrote. On holidays, his sister wrote long epic poems about all the things her family was doing. I remember him showing me something she’d written about Christmas stockings and saying I should write like this, which was not just insulting and dismissive, but totally impossible. To write like that would have required me to be a totally different person. I’ve had concerns about making people mad, but I guess those people don’t really read, either. I would describe your fiction writing as esoteric, yet accessible. Gentle Art is a collection of short stories. One of those short stories is told through quotations from the Book of Revelations, another is written in the style of Choose Your Own Adventure.

I always loved Choose Your Own Adventure books. I’d love to write a proper novel like that, but it’s so difficult. You need to keep so many strands of possibility open. It’s a total headfuck, when you are writing about anything more complex than whether or not there is a dragon in a cave.

Do you have anything in mind for what you’re going to publish next?

I’ve always hated the idea of writing a ‘proper’ novel. Everything of mine is short. I think Death & Facebook is the longest continuous text I’ve done and it’s 30,000 words, so I decided to try and write something normal novel length. Just to not get stuck in the doldrums of only doing insignificant-length texts. Just to prove I can, you know? I’m writing about a girl who ends up living in a car in L.A. - Fiona Helmsley

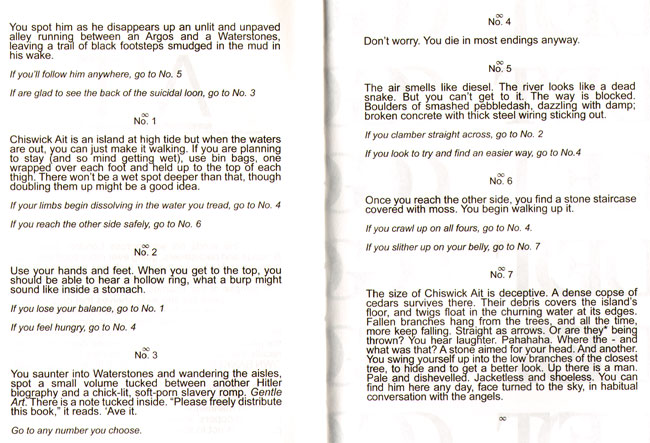

Iphgenia Baal, Gentle Art, Trolley Books, 2012.

Gentle Art is a book about folk devils; creatures at war with respectable society and the conventions on which respectable society is based. It can also be read as a heartrending account of the permanent degradation of men of great talent due to persistent lack of self-control, often indistinguishable from madness. Gentle Art's diminutive dimensions echo the intent of early devotional literature - an almost disposable object, designed for personal edification and spiritual formation. Referencing Stephen Graham s 1927 work, The Gentle Art of Tramping - a manual for life on the other side - Gentle Art is a departure from standard experimental literature: its aim is not to be difficult. Kidnapping personas from real life ("marvellous" George, the petrol-drinker, the ket-head with a woman for a cock and more!) and entering them into absurd formatting - from Choose Your Own Adventure to a compilation of quotes footnoting the entire text - her stories tell of how and why people slip beyond the norms of society, and report back on what lies in store when they* get there. *Everyone has a plan til they* get punched in the mouth.

Interview: Boxing Biannual, Mike Tyson

Interview: Boxing Biannual, Mike Tyson

Experimentalism in literature is often confused with obscurantism. Iphgenia Baal’s collection of sharp, mad stories demonstrates that radical new forms of fiction writing can close rather than widen the gap between author and reader. Incorporating sketches, collages and a welter of typefaces, Gentle Art is a perfect illustration of the innovative means by which the short story can adapt to a new era without having to retreat onto the internet. This is a book to be carried around and consulted. It deals in moments. —Prospect

Each story is unconventional and magical—TPG blogLike [..] lots of thick books imploded into one little one - Moors

Iphgenia Baal, The Hardy Tree: A Story about Gang Mentality, TROLLEY BOOKS, 2011.

The degenerate area surrounding London's Kings Cross is the setting for the debut novella by young British writer Iphgenia Baal.Beginning in the nineteenth century and spanning the next 150 years we are lead through a potted history of the overbrimming St Pancras cemetery, long before the metropolis rode over its bones.

Writer Thomas Hardy was also an architect, and was delegated the unenviable task by the Bishop of London of exhuming and dismantling the tombs to make way for this progress. Here he heads a cast composed of the living and the dead, set into turmoil

as the modern world entrenches on sacred soil.

A post-psychogeographic gothic tale of morality is backed up by a series of forged documents, maps and missives. Somewhere between the two, Baal creates a world where fact and fiction eerily blur; a sanctuary for the over-imaginative.

The Hardy Tree is a book-guide-manual about trains and brains and cliques and freaks. It is a demonstration of how stories are made and an argument for chaos, anarchy and lawlessness. It is also a ghost story. With a happy ending.

Writer Thomas Hardy was also an architect, and was delegated the unenviable task by the Bishop of London of exhuming and dismantling the tombs to make way for this progress. Here he heads a cast composed of the living and the dead, set into turmoil

as the modern world entrenches on sacred soil.

A post-psychogeographic gothic tale of morality is backed up by a series of forged documents, maps and missives. Somewhere between the two, Baal creates a world where fact and fiction eerily blur; a sanctuary for the over-imaginative.

The Hardy Tree is a book-guide-manual about trains and brains and cliques and freaks. It is a demonstration of how stories are made and an argument for chaos, anarchy and lawlessness. It is also a ghost story. With a happy ending.

Told through a collection of fictional ephemera The Hardy Tree begins in 1864, with an account of an early act of London gentrification, kickstarted by the force purchase of St. Pancras's cemetery-slum by Great Midland Railways. The text follows fledging poet Thomas Hardy in his employment as architectural assistant, and his overseeing of the Resurrection Men, a group of louts charged with the disinternment and reburial of 10,000 displaced bodies. Then, abandoning London's dead for a more modern tale, the text rejoins events in 2011, with the advent of the Eurostar casting a remarkably similar threat over the end days of squat party culture.

“Puts the psycho back into

psychogeography but jettisons deep topology for a far more impressive

literary archaeology. Think 'Suicide Bridge' era Iain Sinclair but

with a gallows humour and voodoo swagger. At last, some truly far out

fiction for the post-dubstep generation!" - Stewart Home

"The Hardy Tree; this is the

stuff, to be savoured. A cracking, crackling totentanz."

- Heathcote Williams

"One of London’s most potent

secrets." - Iain Sinclair

“A really wonderful book - full of

energy and delight and humour and lots and lots of London.” - Toby

Litt

"It's brilliant, frankly."

- The Londonist

"Iphgenia Baal has created a

spectacular panorama, a thrilling breath of fresh air, crackling with

life, as well crafted as a Flaxman bas-relief, even if it is about

the lives of the dead…" - Delisia Howard and Chris Price,

Plectrum

As a wild card, I'd recommend readers to look at the work of Iphgenia Baal, whose The Hardy Tree is like Iain Sinclair's wayward, smart-mouthed niece: perhaps more conceptual art than prose fiction, but exhilarating nonetheless. - Stuart Kelly

https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2013/apr/16/choose-best-young-british-novelists

Old St Pancras church yard, just north of the station, is one of those odd and ancient corners of London where history groans from every shrub. We mentioned it only a couple of weeks ago, as the burial place of John Soane, whose tomb inspired the red phone box. The small burial ground, one of the oldest Christian sites in the country, is also associated with Percy Shelley, who used the unlikely spot to declare his love for Mary, author of Frankenstein, while visiting the grave of her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft.

In 1846, the future novelist and poet Thomas Hardy was employed to help clear an estimated 10,000 graves that stood in the way of the rail link into St Pancras. Baal describes the morbid efforts of his 'Resurrection Men' to shift the human remains to a nearby reburial plot, dancing in and out of Hardy's mindset, unearthing local characters and legends, then shifting to our own times and the Channel Tunnel rail link that once again disturbed the ground of St Pancras.

Actually, 'describes' is an insufficient word. This inventive little book pieces the story together through newspaper cuttings, poems, illustrations, tombstone dedications, hand-written letters, maps, penny dreadfuls, acts of parliament...even musical score. It's brilliant, frankly. Part fiction, part fact, the tone and treatment reminds us of Snakes and Ladders by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell, but with a much more accessible narrative. Smashing as it is, we'd love to see this done as an e-book. The countless different formats would work very well on an iPad. - https://londonist.com/2011/06/book-review-the-hardy-tree-by-iphgenia-baal

Fake Ass Bitch

Rot in Pieces

The Seedless Grape

For the Suppression of Savage Customs

Time is a Sausage

TopShop Returns

Heavy Vibrations

Green Felt Hate

Tramps vs. Trendies (live)

https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2013/apr/16/choose-best-young-british-novelists

Old St Pancras church yard, just north of the station, is one of those odd and ancient corners of London where history groans from every shrub. We mentioned it only a couple of weeks ago, as the burial place of John Soane, whose tomb inspired the red phone box. The small burial ground, one of the oldest Christian sites in the country, is also associated with Percy Shelley, who used the unlikely spot to declare his love for Mary, author of Frankenstein, while visiting the grave of her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft.

Among the many other oddments in this place stands the 'Hardy Tree', a lofty ash surrounded by a ring of tombstones. Iphgenia Baal reveals the story behind it in new book The Hardy Tree.

Actually, 'describes' is an insufficient word. This inventive little book pieces the story together through newspaper cuttings, poems, illustrations, tombstone dedications, hand-written letters, maps, penny dreadfuls, acts of parliament...even musical score. It's brilliant, frankly. Part fiction, part fact, the tone and treatment reminds us of Snakes and Ladders by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell, but with a much more accessible narrative. Smashing as it is, we'd love to see this done as an e-book. The countless different formats would work very well on an iPad. - https://londonist.com/2011/06/book-review-the-hardy-tree-by-iphgenia-baal

In The Hardy Tree, Iphgenia Baal deftly “unearths” the history of St Pancras Old Church, through the distraught mind of a then-young architect, poet-to-be Thomas Hardy. Back in 1868, he was commissioned by the bishop of London to supervise the exhumation of bodies in the burial grounds that Great Midland Railways acquired to enter London from the north through King’s Cross. A cheerful job, one imagines. Iphgenia tells his story, combining fact and fiction through newspaper cuttings, headstone epitaphs, correspondence, poetry and illustrations. If you fancy getting to grips with north London on the verge of modernity and seeing it through the eyes of an idealist exhumer, then give this a go. - https://www.vice.com/en_uk/article/gqwgq9/literary-v18n8

Fake Ass Bitch

Rot in Pieces

The Seedless Grape

A World Without Apple (cassette)

Live with JK (cassette)

Supermarket Hell

vodafone.co.uk/helpFor the Suppression of Savage Customs

Y¹, Y², Y me?

Dead Beat EscapismTime is a Sausage

TopShop Returns

Heavy Vibrations

Green Felt Hate

Tramps vs. Trendies (live)

AQNB (Q&A)

Iphgenia Baal was born in London. Her first book The Hardy Tree was published in 2011. The Times Literary Supplement called it a “dizzyling dark, and twisted, collage of a novel.” A themed selection of these short texts were compiled in her second book Gentle Art. Prospect magazine called it “a book to be carried around and consulted.” Once described as “London’s most potent secret” by Iain Sinclair, Baal’s unique voice is a clear rebuke to the current milieu.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.