Paul Hawkins, Lou Ham: Racing Anthropocene Statements, Dostoyevsky Wannabe, 2018.

excerpt

These statements were initially created from texts of radio transcripts between a multi-millionaire, tax-evading racing driver and his Mercedes pit crew during the F1 season of 2015-16, and an article by Mike Hulme: Why we disagree about climate change (Carbon Yearbook). The texts were then processed by various digital means (Markov Text Generator & the Oulipean N+7 Machine, via The Spoonbill generator) and then cut-up and edited.

Lou Ham: Racing Anthropocene Statements, by Paul Hawkins, takes appropriated text from the world of Formula One Motor Racing and creates a series of commentaries. Each page contains just a few lines, staccato sharp experimental poetry that is scathing towards the attitudes of those who participate in the activity. The result is to provoke the reader to consider why it continues, and why the drivers remain so revered.

Climate chaos is a recurring theme, as is the money involved and the hollowness of the spectacle. In stripping away the hype, the inane and damaging nature of motor sport is brought to the fore.

None of the entries are straightforward text given the structure of their transmission. The humour is mocking yet effective in portraying the self-satisfaction of the driver, encouraged and facilitated by their team. The statements are the driver’s voice, divided into countries on the race calendar.

From ‘5 spain’

i’m happy with qualifyingThe narrative builds, a sardonic exposure of a meaningless and detrimental spectacle, a costly entertainment. That cost is complex, and it is this that the percipient text delves into.

fanfares should be ten yelps

i veered

i’m disrespectful

i was really happy with it

well i did get the win

it’s been a loudmouth of work

i was in teasels about it

still there’s no need

to get emotional

i got everything i could

a big congratultions

to this tearaway

This is protest poetry that immerses the reader in the glittery, grubby world of wealth generation and its transient frontmen. Racing pollutes not just the planet but its participants. A challenging, persuasive read. - Jackie Law

https://neverimitate.wordpress.com/2018/07/02/book-review-lou-ham/

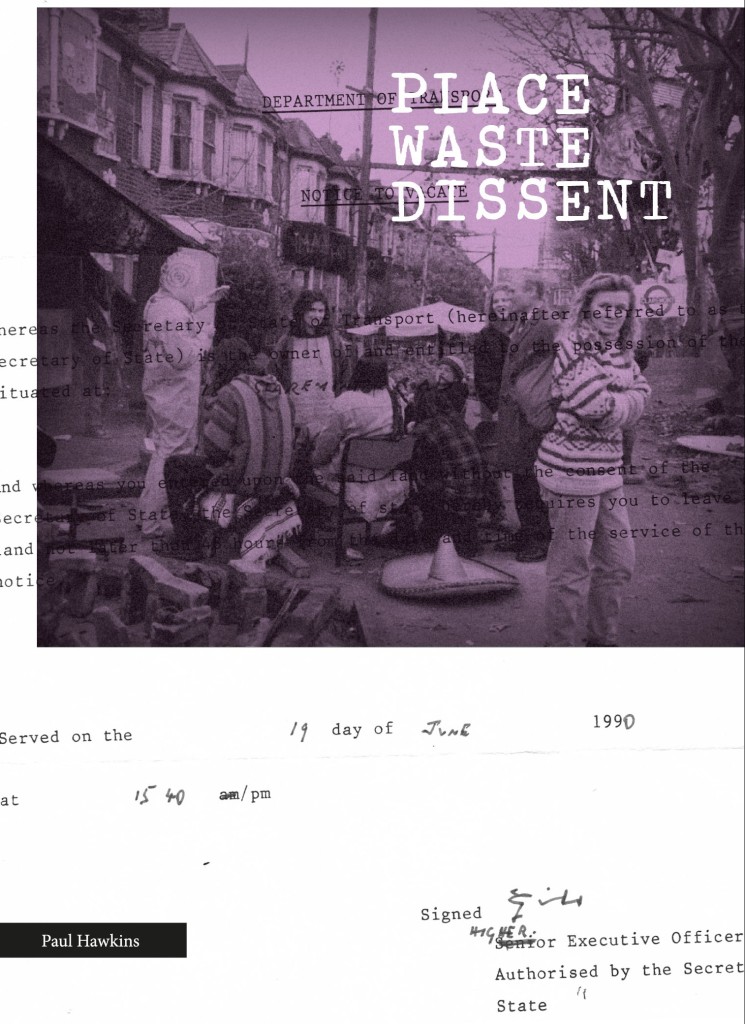

Paul Hawkins, Place Waste Dissent, Influx Press, 2015.

PLACE WASTE DISSENT is a book that takes the aesthetics of poetry as seriously as the occupation and protests that inspired its writing. Having spent three years in the early 1990s occupying properties and protesting in Claremont Road, east London, poet Paul Hawkins maps the run-off, rackets and resistance along the route of the proposed M11 Link Road.

Using the voices of Dolly Watson, Old Mick and many others in avant-garde experimental text and lo-fi collage, he explores place, waste and dissent; the stake the Thatcher/Major Tory government was driving into the heart of the UK.

From Claremont Road to Cameron via surveillance culture and Occupy: transient-beta memory traces re-surfacing along the A12. This collection is an important reflection on a historic site of resistance, offering us illumination, ideas and inspiration for the future. Foreword by Alice Nutter 'Fire sermons and authentic retrievals for a battleground on the edge of the liminal, delivered with spirit and spite and sting. True witness.' – Iain Sinclair

London, August 1994: the revolution is imminent. The odds seem stacked against it: the police, the law, the education system, the media — the whole damn capitalist superstructure, but all it takes is one spark, one flame. Believe me. It is going to happen.

This, at least was my mindset as I hauled my dog-tired body across Leytonstone in search of a bed for the night. A connection in the SWP had offered to put us up for a long weekend whilst we attended the party’s annual ‘Marxism’ conference. We were heading for Claremont Road- a whole street of squats that had appeared sporadically in the media as the focal point of the growing ‘Anti-Road’ movement. None of us were really sure what to expect.

I don’t remember much about ‘Marxism 94’. To be honest, the creeping cynicism that would see me leave the party a year or so later was beginning to take hold of me even then. At one point, a mob of us stormed into the London School of Economics and drove Chancellor Kenneth Clarke off a podium. My friend J. got a little emotional and burnt Clarke’s speech; I took the remains home and stuck them up in my loo. For the most part, however, it was your typical Trotskyite bash- there’d be discussions, someone would get angry in front of us and shake their fist a lot, we’d all nod sagely and agree that Rosa Luxemburg was right. Claremont Road, however, stayed with me for a long time.

Picture Sesame Street as reimagined by Guy Debord and the set designers for Apocalypse Now and you’ll have something of an approximation of what the site was like. The street itself was cluttered with furniture (an outside living room), a zebra crossing that extended over a bifurcated car wreck and into the sidings of the Central Line railway; a giant chess set with tyres and hubcaps for pieces. In amongst this children wandered like Peter Pan’s Lost Boys, dub bass throbbed, threaded with the thick odour of skunk. In one of the houses we stayed in, every inch of the place had been daubed with slogans and outsider art.

The area had been a focal point for squatters and artists since the 1980s, but by the 1990s, as the powers-that-be claimed the land for the projected M11 link road extension, and all but one of the original residents had been pushed out by purchase orders, Claremont Road had evolved into a place where the very fact of residence was intensely political. It may have looked like an all day party, but what these people were doing wasn’t in any sense easy. The Criminal Justice Act of 1994, with its infamous ‘repetitive beats’ clause, had largely been presented in the media as a crack down on the illegal rave scene in Britain. In fact, the act also represented a wholesale attack on dissenting culture, making squatting well nigh impossible, bullying travellers, limiting the right of protestors to assemble and granting heightened stop and search powers to the police. In this sense, Claremont Road was a defiant, two fingered salute to the ascendant forces of conservatism.

In retrospect, the M11 protestors seem to me to be part of a long line of English dissenters, going back to the Diggers, Ranters and Levellers of the English Revolution in the 17th century. All of these groups were Millenarian in nature: they believed that a perfected state of mankind was achievable on earth. Much as us socialists like to pretend otherwise, we’re really no different. If you subscribe to the dialectic then you must believe that history inevitably will lead to worldwide proletarian revolution. The link road protestors were ideologically diverse: anarcho-punks, green hippies, Trots, sometimes just mainstream, middle-class types who’d decided that this was a cause worth fighting for. However, it seemed obvious that Claremont Road was a paradise in continual construction, underpinned by the principles of collectivism and shared responsibility. This was the real world. Everything else outside was just insane. Given half a chance, they’d have made the promised land.

However, just as Millenarianism implies a messianic belief in a promised utopia, it also comes with its own eschatology, the knowledge that somehow these are the ‘end times’- annihilation is just around the corner. All of this was graphically apparent in the architecture of Claremont Road- beneath the Situationist playfulness, this place was a fortress: rope netting stretched across from the roof tops to the tree line opposite; a look-out tower had been extended, impossibly high, on a house at the end of the street. Inside the houses, the protestors had devised multiple ‘lock-on’ points that would allow them to attach themselves physically across the chimney breasts, forcing their evictors to pull the whole place down, brick by brick, before removing them. If you wanted confirmation that the end was nigh, one rooftop featured a makeshift gallows: we were informed in no mean terms that someone intended to hang them self when the goon squad arrived.

Similarly, much as the protestors used an argot riddled with gently ironic hippy code (sabotaging the road-builders’ machinery was known as ‘pixieing’, non-violent resistance was ‘keeping it fluffy’), the air was charged with a well-justified paranoia. This was heightened by the fact that the Road protest also functioned as a sanctuary for the damaged and the fugitive. Amidst the smiles and the jollying on, you couldn’t miss the odd character who wouldn’t meet your gaze and who rarely seemed without a can or bottle in their hands.

They did their best. On one day, we took part in one of their actions, gleefully running rings around construction site security guards until the cranes and diggers were brought to a stop. On the next, we stood powerless as a pensioner was carted out of her house of over half a century and into an ambulance, a faintly embarrassed line of riot police protecting her evictors.

All of this tension, this paradox and contradiction, runs deep through Paul Hawkins’ bleakly beautiful book for Influx Press: Place Waste Dissent. Hawkins was a resident of the road from 1990-1993, and on one level at least, the book functions as a narrative-verse memoir of his time there, though this hardly does justice to its creative verve and invention.

Given his history, he can hardly be blamed for pinning his colours to the counter-cultural mast in his introduction, defining his book as a ‘cross-disciplinary collaboration of avant-garde poetry / collage’ against what he sees as ‘conservative mainstream poetry traditions’. Virtually every page of the book is stamped with left-field credentials: Gee Vaucheresque monochrome montages of photos, police documents, agitprop fliers and eviction notices circumscribe and blend into the verse itself. Oddly enough, this is a book with damn fine production values, even down to the high gloss paper it’s printed on.

Many of the images are deeply affecting of themselves, not least because the faces staring out of them have been caught in a brutally ephemeral slice of history. Everywhere is the sense of something intimate, squashed up to the lens and faintly scary; excised or buried beneath the weight of modern memory.

As I hinted above, dissent has its own traditions, as does the poetic avant-garde. The jaded half of me sees a lot of the techniques Hawkins employs as part of a rather croaky underground lingua franca. People who read this sort of stuff (and I do) will find themselves on familiar territory. Expect Bob Cobbing palimpsests, cut-ups, MacSweeney diatribes, huge chunks of unpunctuated text and cataracts of noun phrases that virtually collapse on your head like falling rubble:

“peeling wallpaper damp walls scummy carpet kids clothes scattered all over the hallway and bannisters over the front-room”

However, Hawkins never seems to use formal experimentation for its own sake. This, after all, is a work dealing with fragmentation in many senses- physical, political, personal — and the ends in this case perfectly justify the means. He’s also got a flair for punkish kennings (‘skip-junkie’) and that puts him in good company with Caedmon and the Beowulf poet.

Towards the end of the book, there is a palpable sense of language burying and consuming itself until only an undifferentiated aggregate remains:

“also funded the smartening / up of a clock tower in / Lea / Bridge Rd funding is lost on retail theatre”

I’m reminded of a snap shot from Burroughs’ Naked Lunch: ‘They are rebuilding the city… yes… always”, except here the apocalypse has a dreadful social immediacy. Hawkins never lets you forget that what was destroyed in this little London reinvention wasn’t just bricks and mortar, but human lives and human memories.

In fact, the two most affecting sections of the book are expressed mostly in a relatively conventional manner. In one section, Hawkins takes on the voice of Dorothy Watson, the pensioner who steadfastly refused to leave. It’s a defiantly unadorned monologue, recounting her history back to London’s blitz years, the isolation of her winter years (‘the days / pass / like Russian dolls / folding into each other’) and the new community that coalesced around her and who made the street a perpetual ‘Coronation’ day street party.

Elsewhere, Hawkins charts his own breakdown due to alcoholism, a terrifying episode in which he and his partner are savagely repaid for their kindnesses to a stray teenager and the descent into paranoia as the evictions begin and police infiltrators slip into the street.

It’s a book that deserves to be read, and certainly beyond the counter-cultural audience that it will immediately attract. As Alice Nutter (she of Chumbawumba fame) intimates in her foreword to the book, much as the M11 link-road protestors faced an inevitable end and an inevitable failure, they changed the world for the better. Exponential road building ceased to be a major part of Governmental policy.

As I write this review, the House of Commons has just passed a bill to begin a bombing campaign in Syria. The protestors have been out in force Parliament Square. More end times. More new beginnings. - Peter Boughton

minorliteratures.com/2015/12/04/place-waste-dissent-by-paul-hawkins-peter-boughton/

Bruno Neiva and Paul Hawkins, Servant Drone, Knives Forks and Spoons, 2018.

Bruno Neiva and Paul Hawkins, Servant Drone, Knives Forks and Spoons, 2018.In the Booklight – bruno neiva, Paul Hawkins & Servant Drone

Paul Hawkins, Claremont Road, Erbacce Press, 2013.

'a valuable voyage, tossed and memory-tumbled over the battleground - ‘self-medicated’ visions of entropy and sensual returns' - Iain Sinclair

'comitted social rebels sharing their lives with down and outs, the homeless, druggies and drinkers, in a loose-knit, tentative community. Dub rhythms (or what Hawkins calls ‘loose-boned blues’) and personal memories drive this collection along. It’s original and moving and I look forward to seeing where Paul Hawkins’ poetry squats next' - Rupert Loydell

'the thirty or so poems in this pamphlet are vignettes of urban life in the 1990s, of grit, pain, love and death, and of resistance and protest. The realism serves up a vivid picture of life on the edge'

Alan Baker

'a pamphlet of protest and ‘broken piano lungs’ that showcases Paul Hawkins’ extraordinary range. Both an experimental and unflinching snapshot of a now lost community, Hawkins sure-footedly sidesteps clichés of romantic dilapidation. This is ‘a survival jive’ for our times' - Claire Trevien

'there’s an unflinching, forensic gaze at work here that holds you spellbound; you don’t want to look but can’t help it. This is the heart of darkness in the east end of London during the Thatcher years: depression, addiction, evictions; the tide and time of love, sex, the bitter fight to overcome. Although it is dark, it is not entirely hopeless, there are moments of tenderness and unity that build a barricade against despondency. The poetry is rich and lyrical, with a probing experimentalism that challenges both the subject and the form, from sonnets to collage and found poems. This is a joy-ride of a pamphlet, so strap yourself in and feel the buzz' - Neil Rollinson

reviews:

Rupert Loydell, Stride Magazine

Alan Baker, Litter Magazine

Billy Mills, Sabotage Reviews

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.