Chris Campanioni, A and B and Also Nothing, Otis Books - Seismicity

Editions, 2020.

“How do we re-write American identity? Start by exploding the canon. Chris Campanioni begins by adapting (re-writing?) Henry James’s The American and Gertrude Stein’s “Americans” through an amalgam of annotations, observations, aphorisms, and asides, dissolving the boundaries between journal and novel, autobiography and fiction to enact the correspondence between all things when they are copied out. Then he goes further, imagining several other books inside this one, including an exploration of the ways in which “migrant illegality has been fabricated and shaped since September 11, and how these processes parallel the expansion of criminalization in an increasingly securitized and (border-) patrolled United States, and how this might inform a critical evaluation of technology’s role in capturing and containing bodies: the specular and surveillant logic deployed for the divestment of human rights—to dispel bodies or, alternatively, to keep them in check.” More than anything else, it is this hypothesized convergence of the real, the not real, and the not yet real that propels A AND B AND ALSO NOTHING toward a blueprint for American identity built on errancy and errantry, hospitality and mutability, and a reevaluation of the exclusionary practices premised on the fetishization of origin and the original; the singularity of specialization. “Against nothing,” Campanioni writes, “if not against expertise and the territorial character of art.” In introducing the game and inviting all of us, A AND B AND ALSO NOTHING is both a call and a response to the avant-garde, an attention to the community of neo-mestizo writers and writers of color who have, consistently, been left out of its genealogy. -from the SPD website

On Instagram, the fast-moving writer Chris Campanioni goes by the name “chrispup.” The “pup,” I think, signals his readiness, as a writer, to leap and run and frisk and never regret. In poetry and fiction, in critical essays and new-media hybrid pieces, in sentences alternately lavish and trim, he breaks the sound barrier. Like José Lezama Lima, Campanioni finds no syntactic or figurative posture too baroque to try on for size. Migratory poetics is among his current subjects; his protean energies—his willingness to go everywhere with a thought, and to spin an association out to its most eerie and electrified edge—elevate him to a rare rank of writer. Campanioni is the traveler who, like Hervé Guibert, rides language without ever stopping to worry that language might not cooperate.

His new book, A and B and Almost Nothing (Otis Books | Seismicity Editions), began its life (I’m tickled to say) in a seminar he took with me on Henry James and Gertrude Stein. In it he unfurls a brilliant manifesto-aria on what it means to attend, to concentrate, to listen, to resist, and to reckon. Imaginatively jamming together James’s The Americans and Stein’s The Making of Americans, Campanioni reshuffles nationality, borders, and genealogy. The son of Cuban and Polish parents, he shows us who was left off the page; his bricoleur scissors work magic with available materials because he knows afterward how to be free with the glue. He writes, “when I am whirling rapidly and dizzy with possibility or pleasure, a friend might tell me to cut it out.” Fascinated by Stein’s “continuous present,” Campanioni keeps textuality, that glittering subterfuge, whirling: I hope he never cuts it out.

—Wayne Koestenbaum

While writing your book, were you thinking of The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again)? B, the other voice on the line. A, the originator. A and B, interlocked voices, codependents, alter egos, echoes.

Chris Campanioni

I hadn’t thought about that text in a while, but Warhol’s work remains instructive for my project of name-dropping and the play of representation. I’m interested in the moments when “B and I” become merged, or reversed, reversible; when “proper” names become emptied of meaning. The undecidability or indeterminacy of the doubled, troubled, “I” signals my attempt to form a lineage with James and Stein; “J and S” become entangled with my own dad and mom, “J and S.” The immigrant perspective confounds cultural nativity. In the book, this tension begins to confuse or fuse with the national literary canon: Stein is truly the mother of us all, and the James I am concerned with isn’t a James but a Juan. These coincidences manufacture more coincidences, self-reproducing—that’s kind of how slippages work, right? Fabric loosens until the clothing unravels all by itself—so The American’s “Christopher” is stripped down, in my version, to become “cc” (my authorial initials or signature) with the reminder that “no one calls me ‘Christopher’ except S, whose name, in Polish, is spelled with a Z.” These moments of clarification only constitute another slippage.

Naming is also important to your project, in your latest essay collection, Figure It Out, and elsewhere. And yet I’m equally struck by the moments where you negotiate the decision to name, to alight upon, to recognize, to remember, to commemorate or designate—whether person or room—with the erotic charge of anonymity, indirection or indiscretion.

WK

I like to name, and name-drop; proper nouns are my carbs, a glad addiction. Your writing has a beautiful sheen of non-specificity; you disclose and cite, but also enjoy veils. If Stein, Henry James, and you were to compare styles of veiling, how would you describe your veil mode to theirs?

CC

I want to play voyeur and exhibitionist—maybe to be the voyeur of my own exhibition—which necessitates so many veils, so much unraveling, a word that has always confused me but also captivated me. Am I being unwound, undone, or does the un- reverse the ravel operation, return or rewind me to myself, differently? I’m excited by iterations and a style of writing that I think of as a reprise. What I hope to hear or sound out is a mise en abyme without any hierarchically different levels: no subordination, only similarities—the text as a procession of resemblances.

My veil works by disclosing a lack: no distinctions between myth and memory, fiction and experience, waking life and dreams. When I read the text back, I want the text to harvest a latent haze, from which everything is familiar and nothing is recognizable. You’ve taught me so much about my work, about a mode of writing that insists upon transparency while problematizing the texture of the confession. I think about what that makes possible for the text, what it invites as a readerly behavior, to reorient the ways in which we have been taught to read “poetry,” “autobiography,” “fiction,” or any other genre.

You, too, want to imagine an alternative ecology of literature but also language. In Figure It Out the “subjects”—punctuation, the sentence, translation, cum-bucket consciousness—aren’t really subjects but predicates. The order of the English sentence has been recast, allowing you permission to claim nearness to other things while displacing an original investment, a sleight of hand that relies on an attention to tempo but also to petrifaction, to placement. Rather than excluding “all culinary delights,” as Adorno has recommended, you relish the body, what it gives and gives off. I want to connect this generosity to your pedagogy, your ability to make everyone feel like contributors to a project that values, as you write, the “important” alongside the “extraneous.”

On the first day of your seminar on notebooks, you told us, as addendum to instructions for our weekly assignments: “you can always write about something else.” In your James and Stein seminar, your guidance to my classmates was “cultivate affinities.” In any project of catalog and collection, the path of resignification is sacred; your work not only cultivates affinities but commemorates and eulogizes. Transference, compassion, and empathy organize your writing’s dynamic wish: the task to imagine the daily experiences of people—and objects—we could not possibly know, and to attend to the lives of people and spaces that have since been lost. We each have taken seriously the irregular accounting as a poetics that is both processual and theoretical, an engine that can alter the temperature of texts without warning. What can you realize in the notebook that you can’t attain in other modes of composition? Tell me about the gift of transcription. - The Unconditional Hospitality of Composition: Chris Campanioni Interviewed by Wayne Koestenbaum A conversation that could be a poem, a diary entry, or a game of tennis about how writing reinvents itself.

Read more here: https://bombmagazine.org/articles/chris-campanioni-interviewed/

The Internet is for real inverts the autobiography in the age of dis-integration, calling into question all narratives of national belonging. ‘Right? So that the universe could eat me & send traces everywhere, this book or the backroom countertop audio of the same scene.’ Sifting through—and re-writing—the films of Godard, the novels of Henry James, Twin Peaks, VR fantasies, Internet ephemera, and his father’s dreams of Cuba, Chris Campanioni reveals the materiality of our spaceless encounters, and forces us to reckon with the violence hidden below the sleek 4G surface. As he revisits his parents’ migration to the United States and his own first-generation dislocation through a blur of poetry, prose, and screen-play, Campanioni shows us that in a culture of self-dissemination and unlimited arrivals, we are all exiles under the sign of a mythical return.”

“the Internet is for real is obsessive, it’s compulsive—it throbs with the autonomic flush of being ‘seen,’ and the reflective terror of being ‘known.’ It scared me the way open water scares me, or outer space the vacuum of black. You read this book, and the book reads you right back.” — Tommy Pico

“Campanioni’s writing is playful, unflinching . . . a much-needed reminder of our endless potential for duality, in a world that too often suggests only polarity is possible.” — Harvard Review

“Award-winning author Chris Campanioni may, for better or worse, be the voice of our generation in which the internet is our stomping ground and making eye contact with our friends and family is a rare treat . . .” —Your Impossible Voice

“A hashtag, abbreviated quality . . . both deeply intimate and thrilling.” — Metal Magazine

“Bolaño meets DeLillo meets Borges . . .” —Red Fez

“While Chris Campanioni, like Borges and Cortázar, likes to play with form and perception, he doesn’t jeopardize the story he’s telling. He’s a performer. He knows when and how to reward his audience.” — Dead End Follies

“the Internet is for real is like no other book you’ll read this year. Border-busting, fearless, and exquisitely alive, Campanioni’s latest work thrusts readers into a world of self-projections and bold intimacy, techno-anxieties and cyber-bliss, political whirlwinds and cultural homecomings. the Internet is for real again proves that Chris Campanioni is his own remarkable genre. This is a must-read for the ‘post-Internet’ age and beyond.” — Jennifer Maritza McCauley

“Critical theory collides with popular culture, technology, and personal narrative … a wonderful collage-like quality in its language, as well as in its form … the page becomes a visual field.”

— Kenyon Review

In his book The Dialogic Imagination, M. M. Bakhtin observes that “the poetic symbol presupposes the unity of a voice with which it is identical, and presupposes that such a voice is completely alone within its own discourse.” For Bakhtin, one of the distinguishing features of poetic language is the use of the image to convey content that is narrative, emotional, or philosophical in nature. Even more importantly, the poetic image, in Bakhtin’s estimation, arises out of the sonic and stylistic terrain the poet has created, responding to, and directly informing, the behavior of the language itself.

Two recent hybrid texts explore, and fully exploit, the possibilities that poetic language holds for innovative prose writing. Chris Campanioni’s the Internet is for real and Elizabeth Powell’s Concerning the Holy Ghost's Interpretation of JCrew Catalogues invoke recurring imagistic motifs as structural devices, the end result being a narrative arc that is not easily charted by familiar literary conventions. With that in mind, the image, for both of these gifted prose writers, lends a sense of order to, and circumscribes the boundaries of, the imaginative terrain that these vibrant, complex characters traverse. Though vastly different in style and aesthetic approach, these innovative practitioners share an investment in expanding what is possible within the artistic repertoire of fiction, carving a space for lyricism, ambiguity, and experimentation within the familiar act of storytelling.

This destabilizing impulse is most visible in these writers use of metaphor. As each book unfolds, metaphor is no longer mere adornment, a rhetorical flourish at the end of a lovely stanza. Instead, vehicle and tenor become organizing principles, offering a source of unity, and productive tension, within each novel’s carefully considered meditation on the nature of representation. As Powell herself writes, “…until we can see clearly the way of the flower to the sun, we shall dwell in the photograph of the free world, forever and ever. Amen.”

...

Like Powell’s novel, Chris Campanioni’s hybrid text, the Internet is for real, takes as its primary consideration the necessary tension between reality and representation. For Campanioni, this friction is amplified by technology, social media networks, and the their undeniable presence within interpersonal relationships. The work’s central metaphor, then, becomes the photographic image as signifier, rendering the physical body an “immaterial daydream” and a deceptive chimera. As Campanioni himself asks in one of the book’s more essayistic sections, “The camera is us. We have become so fully integrated into the machine as to become its greatest development: a living snapshot.”

If the boundary between reality and representation has been dismantled by the rise of readily accessible social networking, what does this mean for art? In Campanioni’s estimation, the parameters of art are then expanded, as the most quotidian tasks become, at turns, performance and narrative, our being in the world a “visible plastic symbol,” an adornment, and a satiric impulse.

Campanioni writes, for example, in one of the book’s many discrete prose episodes:

You make your way through a rave-like jungle as each crystal bulb pulses and changes color, swaying as though you are the jungle: a body forgotten or fused with an ecosystem or system of hardware. The self that has left its own skin.

The word “system” here is telling, as Campanioni reminds us of our place in the various economies of language and representation that circulate around us. Social networks, then, become a kind of auction block, the subject’s performance a commodity, its artifice intended to secure a place within this larger system of valuation. By describing the self as “a rave-like jungle,” he posits the individual as a nexus for transpositions, transactions, and transformations when considering these larger systems of labor and value. However, Campanioni’s work is most provocative in its considerations of deception in these technologized environments, in which the photographic image becomes a way of reclaiming power and agency within a broken cultural mechanism.

As Campanioni himself asks, “Send this message without a body or a subject?”

brooklynrail.org/2019/03/books/Beyond-Metaphor-On-Prose-by-Chris-Campanioni-Elizabeth-Powell

Chris Campanioni, Drift, King Shot Press, 2018.

A couple arrive at a Mexican resort town as grisly murders escalate, crowds converge in Manhattan for an End of the World party, a journalist’s search for the real story leads him to the facts of his own disappearance. . . Chris Campanioni’s DRIFT is an apocalyptic riddle, a countdown to dead time, where what’s scripted begins to blur with what’s real and the pervasive fear of being surveilled is matched only by a desire to keep filming.

“DRIFT is a dizzying, nightmarish journey through our final days. This is one of those unique works, existing somewhere between Julio Cortázar’s 62: A Model Kit, Richard Kelly’s Southland Tales, and maybe Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia . . . Campanioni has written an hysterical, existential glimpse of a parallel now populated with disappearing lovers, converging singularities and technological depression.”—Chris Lambert

“I want to capture everything,” a character says in the opening pages of Chris Campanioni’s new novel Drift, echoing the very millennial compulsion to document everything, and mirroring the attitudes of the twenty-somethings that inhabit the 400-plus pages that follow. Written over the course of ten years, the book fits nicely into Campanioni’s output, sliding next to last year’s equally impressive, The Death of Art (C&R Press). Hard to categorize as ever, Campanioni has returned with more fractured narratives filled with an unlikely pack of auto-fictional models, college kids, Jersey Shore party-seekers, extroverts, and cynics, all seeking to document their existence by all means necessary. Channeling Bolaño’s 2666 formal structure, Chris Campanioni has crafted another terrific glimpse into our modern anxieties, and our compulsory need to “capture everything.”

Drift is composed of six sections, four of which are based on seasons of the year. Each section follows a variety of non-linear narratives. Mostly we follow a model named Chris Selden—presumably the auto-fictional Campanioni. The reader traces Selden through photoshoots in Palm Desert, trips to Brazil, romantic entanglements, and more. Selden, equal parts cynic and playboy—a la some character from Rules of Attraction or Glamorama era Ellis— believes that everyone born in 1985 is “doomed.” He also speaks at great length about resenting the artist’s insatiable need to observe:

The fact that I can’t look at someone, at anyone, without sizing them up, without writing them into the story. Every encounter in life viewed from above; a tracking shot from the camera eye of a cruising hawk. It wears on me.

Cameras constantly pace behind most of the proceedings in Drift, from photo shoots to coffee shops in NYC. Much of the narrative is described as if everything is being filmed, and the line dividing what is being recorded or not within the narrative becomes nebulous. Words like “tracking shot,” “scenes,” and “stagehand” are used in subtle ways intermittently throughout to elevate the feeling that everything is being captured, recorded.

Like The Death of Art, Drift captures aspects of the modern millennial zeitgeist perfectly. Characters constantly alternate between deciding to document the present moment or just experience it. Campanioni’s characters often crave the actual experience but oftentimes they find themselves living in a purely fabricated representation of experience. The world as simulacrum occupies big ideological spaces within Campanioni’s work. In a passage titled “This Must Be The Place” (one of the many Talking Heads references), the narrator reflects on the fallibility of memory:

Memory can change the shape of a room; it can change the color of eyes, hair, a name or a face. It is not a record, it is an interpretation. A representation of the actual experience. A fake.

Or take for example Selden’s experience as a model in Palm Desert. When time is running short and the crew are unable to shoot in neighboring Idyllwild in the mountains above the desert, the crew recreate the backdrop of Idyllwild on the computer.

Idyllwild was the greatest thing I’d never seen…tall pines, sweet-smelling cedars, legendary rocks…eventually they’ll stick my body somewhere among those pines…

Here the world of simulation has become more ideal, more desirable than the actual world, than actual experience. The main conflict to be found within Drift is the tug and pull between real experience and manufactured, surveilled experience.

The allusions to 80’s new wave and indie music abound through the pages of Drift. Chapters titled “Bizarre Love Triangle” and “Girls on Film” broadly work to highlight some of the themes within the text, but also seem to be calls to Campanioni’s musical literacy, if anything else. Twenty-somethings hop into cars where the stereo plays Talking Heads, and casual conversations are had in coffee shops about the legitimacy of genre names like “dream-pop” and “chill-wave.” In Drift, things are begging to be defined and made tangible, but in a world that feels like a production set, real meaning and the correlated experience are always out of reach.

Sections titled “Atrocity Exhibition” (I-V)—borrowed from the Joy Division song of the same name—fracture the narrative even further, providing little vignettes that confound, further exploding any semblance of narrative. This almost apocalyptic stylistic approach works in tandem with the apocalyptic tonal nature of the book. Not only are there end of the world parties—including heightened anxieties around the end of the Mayan calendar (2012)—but the book as a whole feels prophetic of a certain “end times” mentality.

Much like in his previous novel Death of Art, Campanioni wrestles with his public image and how it is represented online. In one section, we are privy to a long transcript of messages Campanioni—or his auto-fictional self Chris Selden—has received from admirers across social media. Inquiries range from requests to befriend Selden, to questions about his diet and exercise routine, while other inquiries prove to be more probing and vaguely problematic. This section works well to display perhaps the ramifications of a public life like Selden’s that is readily available for consumption, for commodification.

Like most of Campanioni’s work, his new novel works best when it’s ideas are constantly in motion from one page to the next. Drift could not be a more apt title for a book whose ideas drift from page to page, appearing like a revelation and then vanishing just as quickly. Shifting from autofiction, to memoir, to metafiction, and realism, sometimes all within the course of a few pages, Drift is a book that begs us to put it back together, to frame our own narratives, and to follow its often transcendent insights in our own lives. - Michael Browne

http://angelcityreview.com/drift/

Have you ever stopped to analyze the flow of thoughts inside your head while commuting or running errands? The mind is an unruly place in which we live other, different lives than the one we're actually living. The one we should care about. I do this exercise often because freaking myself out is a low-key passion of mine and I've thought of it while reading Chris Campanioni's novel Drift. I'm not even sure it qualifies as a novel, but I'll use the term for lack of a better one. But man, it was quite a head trip and I've enjoyed it despite not understanding everything.

When I say Drift barely qualifies as a novel, it's because it's a series of interrelated stories. They're all based around a recurring character named Chris Selden who, from what I gathered, is a metafictional stand-in for Chris Campanioni himself. Selden is a committed actor, model and well... duh, writer, who everyone loves for reasons that sometimes have to do with who he really is and sometimes have to do with the person he pretends to be for a living.

And when you're committed to your craft the way Selden is, it sometimes becomes complicated to differentiate reality from film, fabricated news stories, warped perception people have of you and the fiction emerging out of all this.

Of course, Drift is a novel that questions the nature of reality. It asks the question: what is reality when your life is devoted to creating different forms of fiction? Do you have such a thing as reality or is your reality the sum of your fictions? That's a lot of mental juggling, I know. But, I've enjoyed Drift because I believe this question applies to more or less everyone. And this question is exactly why I believe fiction is important: it can inform and shape your reality if you let it. Drift makes its case for it in a warped and dramatized way because it aims to entertain first an foremost, but it's not any less pertinent.

Drift doesn't resemble anything I've read before, but if I had to give you a comparison to writers you may know, think Jorge Luis Borges or Julio Cortazar. Maybe throw a little bit of J.G Ballard's apocalyptic imaginary in there. It won't be everybody's cup of tea. Novels like Drift don't straightforwardly deliver themselves and require active participation. It's not every reader that will accept having to make efforts to connect the dots. But while Chris Campanioni, like Borges and Cortazar, likes to play with form and perception, doesn't jeopardizes the story he's telling. He's a performer. He knows when and how to reward his audience.

So, I'm proud of myself here. I managed to explain to you why I enjoyed Drift and say almost nothing about Chris Selden's quest, which is another layer to this novel I'll leave you to unfold. This book doesn't have mass appeal at all, but it has a magnetic power that will draw people to it. Drift isn't a book you can read casually, at the beach or the airport. It chooses you. Its fleeting, shifting sense of reality and metafictional will confuse and alienate many readers. But it will also captivate those meant to read the book. I can't tell you whether to read Drift or not. It's a conclusion you need to draw from yourself after reading this review. But know that it's far removed from conventional storytelling. - Benoit Lelievre

http://www.deadendfollies.com/blog/book-review-chris-campanioni-drift

In one of the first stories of Chris Campanioni’s Drift, there is a photographer named Jared Garrett who repeats over and over again his desire to capture everything, going so far as to wonder – beneath a purple sky, listening to coyotes howl in the distance – if he could capture the silence within a moment. This character’s fervent aspirations reflect what the author seems to be attempting throughout the rest of the book: to capture the things we cannot see, to describe what we have no words for. Campanioni digs deep, weaving together the mundane and familiar as well as the bizarre and glamorous in ardent pursuit of the right words that could express feelings within moments where most people simply say, “You had to be there,” or, “you have to experience it to know.” Here is how a character describes blacking out:

http://vol1brooklyn.com/2018/04/17/capturing-the-silence-a-review-of-chris-campanionis-drift/

Chris Campanioni, Going Down, Aignos Publishing Incorporated, 2013.

Named Best First Book for the International Latino Book Awards, one of the best novels of the year by the Latina Book Club, and a "must-read book" by the New York Post.

"Campanioni's life experiences give him a unique perspective. Rather than writing about fashion or journalism as an outsider looking in, he draws from a rich array of personal stories. The inquisitiveness and attention to detail he needed as a reporter has fueled Campanioni's fiction writing." - Manhattan Times

"If Gatsby is considered the last great 'New York Novel' ... then Going Down by Chris Campanioni is like Muhammad Ali in the Fight of the Century. The writing style is like a child of Martin Amis and Reinaldo Arenas, full of linguistic poise and observational quips." - The Banner

You always want to act like you’re in control. Even if you’re only pretending. – Mark Van Etty

Engaging. Captivating. Exciting.

New writers are always told, “write what you know.” No one can dispute that Chris Campanioni knows a thing or two about being a model and so we are not surprised that his first novel would be set in the glamorous world of fashion or that our protagonist would be a mini-Chris. What we are surprised at is at the novel’s dark tone. Our hero is a tragic figure -- restless, bored, lost. His backup plan falls through, and it is not until tragedy strikes at the heart of him, that he finds the courage to step back from the fame, the money and start anew.

Campanioni writes with a frank, open, engaging style, with great narratives, vivid descriptions, lots of action, and numerous flamboyant characters. The author does gloss over the drug and sexual abuse rampant in the industry, and we must admit the endless flashbacks are distracting. But despite all that, readers will still be captivated by his insights into the world of fashion and the life of a male model -- an extravagant world everyone dreams of but few ever enter.

BOOK SUMMARY: Chris Selden is a pampered, privileged college grad from Bergen County, New Jersey. He is a “poster boy” for the new breed of Young Productive Americas but with no prospects of a job of any kind. In fact, he’s what could be termed an educated bum, living at home with his parents with big dreams of becoming a journalist. And though, he does get a job as a writer at the local newspaper, it is modeling that pays the bills.

A writer by day, a model-party boytoy by night, Chris pursues both his passion for literature and his modeling career. Within months, his face is plastered all over billboards and magazines. Modeling leads him to acting and he is soon the newest, but nameless, bartender in Pine Valley (OLTL soap). His Cuban mother Ana is super proud; while his white father wants him to find a “real” job.

Chris is soon meeting the right people, going to the right parties, getting the call backs, enjoying the fame and fortune coming his way, while his real love of writing at the newspaper proves unfulfilling. He soon learns that journalism is not literature, and when the office finds out about his modeling, he becomes a joke.

Our hero becomes a tragic figure – bored, morose, jaded. Like in his favorite novel, THE PICTURE OF DORIAN GRAY by Oscar Wilde, Chris is pursuing a life of beauty and fulfillment of the senses but the wild life of debauchery has an adverse effect on him. He may be smiling for the cameras but inside he is depressed, unhappy. The earlier, naïve Chris had always planned to have a backup plan if he ever found himself stuck somewhere and wasting his time. Here he was wasting his life away, and though he kept hoping his writing would save him, it doesn’t. In fact, being a journalist is boring and Chris soon quits New Jersey and his day job to devote himself to modeling in New York.

Our hero soon becomes lost in the shallow, cut-throat world of fashion; Living in a luxury penthouse with other models and wannabes like himself; Partying the night away hoping to be seen; sleeping with an endless parade of women. Chris both enjoys and abhors his existence, but when a budding film producer offers to make a documentary of his life, Chris is all for it. The documentary is a hit and makes it to the Cannes Film Festival. Now his fame is international. And it is not until his loving mother develops dementia, that Chris realizes the emptiness of his life.

With his mother’s death, Chris finally admits and acknowledges that he was “going down;” sinking into despair. He runs off to Brazil to find some peace and do another modeling gig, another soap role. He finally admits to himself that he is lost in a dream he never wanted, and this time finally, truly breaks away and returns to writing; hoping to finally find peace and redemption in literature. - Maria Ferrer

http://www.latinabookclub.com/2013/12/review-going-down-by-chris-campanioni.html

Chris Campanioni’s ambitious debut novel, Going Down, tells the story of model and journalist, Chris Selden. Unsure of what to do post-college, Selden finds himself tempted into a world of popularity and commodification as a fashion model. He is ultimately consumed by his own spectacle.

The book opens with less of a scene and more of a barrage of images–flashing lights, demands for “languor” and “desperation,” a flurry of production assistants who seem to suffocate the protagonist. It is difficult to find one’s bearings in this world. Flashbacks come early and often; perhaps this is meant to represent Selden’s fragmented voice as he musters through his identity crisis since it has the chaos of stream-of-consciousness without using first-person.

For much of the book, Selden works as a model by day, a journalist for The Star Ledger by night, and in the hours in between, the perpetual partying “it-boy.” He approaches both potential careers with a sense of irony and heavy skepticism, but he ultimately gives up his position as a reporter. Selden is psychologically thin, morose, and somehow amidst all this fevered activity, bored. With existential angst and cynicism in line with Holden Caulfield and Quentin Compson, Selden seems to both condemn and adopt the principles of this nasty, image-obsessed world; however, this book is not the traditional bildungsroman it is touted to be since the protagonist fails to reach much moral or psychological growth despite a severe personal loss and international travel. If one continues to participate in a lifestyle one abhors, how much growth can occur? The reader is held at arm’s length from the protagonist at all times and so, we wind up with an unreliable narrator who professes to want to write more than anything, but his actions throughout the book say otherwise; he’s as much in love with the image of the writer as he is in love with his own image.

However, if the reader pays attention, he/she can also see Selden’s vulnerability and self-doubt about his own creative abilities: “In college, he had written a few things that had excited a few people, but he lacked the confessionary air of honesty necessary for a writer of any import, and it was this inability to get to the heart of anything that reduced his fiction to a reprinted still life of water lilies; a pretty picture, sure, but nothing as transposing as the real thing. He stopped short in the excavation because he was afraid of what he might find” (8).

Some time later, in one of many confusing italicized sections, the narrator claims Selden has “fashioned himself an existential hero in this way; tortured by time and circumstance, alone against this onslaught of immovable forces we call fate…But rather than feeling sorry for himself, he thrived on it; this secret knowledge of self-awareness, a distinction of separation which bordered on superiority. In short, he was totally delusional.” Is this Selden narrating from a great distance? Where does one land when even the narrator and protagonist profess knowledge of the world’s construction, its artifice? I don’t know, but maybe that’s the whole point.

Midway through the book, Selden is living in a luxury apartment owned by a wealthy family and occupied by their spoiled daughter and the transitory coterie of people she finds interesting. It’s an endless, mind-numbing party of self-worship. Everyone sleeps around, but even sex doesn’t hold anyone’s attention. This world is reminiscent of Andy Warhol and his Factory exploits; as I read, I kept thinking of Warhol’s famous quote, “I am a deeply superficial person.” Selden continues to love and despise himself. Of course it seemed inevitable to him that his friend Dave made a documentary about him. What else could these characters who are not friends, and are, at best, shell characters (mere projections of Selden’s own eyes), do but point their gaze at him, and share it with the masses? It’s gaze upon gaze upon gaze–a dizzying Russian doll construction. Selden never decides “whether it was better to be the art, or the artist” (127).

As much as I admire Campanioni’s ambition and, at times, playful structure and form, it is not as successful as say Jennifer Egan’s similar approach in A Visit From the Goon Squad. Campanioni isn’t dealing with an expanse of time like Egan; as a result, rather than enhancing the story, the structure becomes distracting. Campanioni is influenced by the Situationist International movement, in which avant-garde artists and author/theorist Guy Debord claim, “All that was once directly lived has become mere representation.” Since Debord committed suicide in the 80s, I wonder how he would interpret social media and contemporary society. Campanioni raises salient questions with his Debord-influenced, chaos-driven prose style especially when taken in context with Debord’s claim in his “Commentaries on the Society of the Spectacle,” that all life becomes “repressive pseudo-enjoyment.”

Pseudo-enjoyment seems to be Chris Selden’s underlying thesis on modern life; as a result, things get dark, but part of me wishes Campanioni had kept going, pushed further, and shown us what happens to Selden when he loses everything, when this world obsessed with perpetual youth, constructed beauty, and excess finally turns on him. He knows he’s addicted to this life, but he has yet to hit bottom.

All that said, Going Down has many lovely and tender moments, most of which occur with his family, and in particular between Selden and his Cuban mother, Ana. In one of the most poignant scenes of the novel, Selden wonders if he should tell his mother the truth about his dissatisfaction with living life as his own doppelgänger:

“If he told her everything, she would be overwhelmed and disconnected, a story without any context…And then there was the matter of removing the blanket, crushing the façade and shattering her world. Chris knew how painful that could be. It reminded him of the first time they all had huddled into the Volvo station wagon, making their way south to visit his abuela in Miami. A jovial family trip had turned devastating for him in Jacksonville when the realization hit Chris: he would not meet a smiling Mexican with whiskers and a poncho, welcoming them “South of the Border” at he end of their journey. That he would, in fact, not meet anyone named Pedro during any portion of the trip. He had never really stopped looking” (128).

It’s no secret that Campanioni himself is similar to his protagonist; he is a model, an actor, a journalist, and creative writer. I look forward to reading his future work when he pushes to fully excavate, as I’m most interested in what he might find. - Beth Gilstraphttp://www.fjordsreview.com/reviews/going-down.html

Brooklyn is chock-full of unique and talented writers, but Chris Campanioni stands out. He began his career as a journalist, which is not particularly unusual, but he also works as a model by day and teaches fiction writing and literature in the evening as a professor at the City University of New York. The Brooklyn Heights author, who recently released his debut novel “Going Down,” will appear in Brooklyn Heights to discuss his book this Sunday, Nov. 3, at Red Gravy.

A former journalist at the San Francisco Chronicle and the Newark Star-Ledger, Campanioni started writing his novel over six years ago when he began working simultaneously as a model and a copy editor. “In 2007, I was mainly exploring the issue of ‘growing up,’ especially in today’s society in which the sociological parameters of adulthood have become increasingly outdated,” said Campanioni.

As he delved deeper into his writing, however, Campanioni realized the stakes were rising. “The novel became more than just a coming-of-age story and an exploration of my generation,” he said. “Going Down” focuses on the fashion industry from the lens of a Cuban-American journalist and male model. Struggling to manage such separate careers, the protagonist soon realizes he is living two lives, and as each becomes increasingly complex, he feels he is losing sight of himself. While Campanioni’s book explores the distinct experiences of being in the newsroom and on the runway, it also gives voice to a Latino model – a traditionally underrepresented figure.

Though Campanioni is often traveling for work, he feels fortunate to call Brooklyn home. In fact, Chris Selden, the protagonist in Campanioni’s novel, jokes at one point in the story that sooner or later, everyone moves to Brooklyn. That rings true for the author himself; in a recent interview Campanioni told the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, “My mother actually lived in Greenpoint when she came to the United States from Poland, so I was always familiar with that area, but I became acquainted with Brooklyn Heights when I began dating my girlfriend, who has lived on Hicks and Joralemon since she was a child.”

As a writer and model, aesthetics are particularly important to Campanioni. “Brooklyn Heights is one of the most picturesque places I’ve ever lived in—so I feel especially fortunate that through all of my work-related travels, I’ve stopped here for the last three years,” he told the Eagle. “Because I do much of my writing while I’m on the run, and more specifically, running, the location is especially great because of all the fantastic trails bending from Red Hook through the Promenade and into DUMBO.”

Campanioni also values the distinct literary culture that permeates Brooklyn. “I love the energy and passion, and also, the committed audience following; you don’t see weekly readings on this level in other cities,” he said. “With so many established and emerging authors and artists situated in this area, there’s no better place to be as a writer and a reader.” - Samantha Samel

brooklyneagle.com/articles/2013/10/30/heights-writer-model-celebrates-debut-novel-at-red-gravy/

Chris Campanioni, Death of Art, CR Press, 2016.

Death of Art dissects post-capitalist, post-Internet, post-death culture; our ability and affinity to be both disembodied and tethered to technology, allowing us to be in several places at once and nowhere at all.

“The future is trash. Recycling it, re-arranging it. Making it beautiful again.”

“Lately I had been thinking about writing a memoir because everything else I’ve ever written is a memoir while pretending to be something else and I figured it was time I did something else, which was a memoir. So much of my life is predicated on pretending or performance. Language had become another performance for me. One in which I could show off and show myself. At the same time.”

Chris Campanioni starts by cutting out his face in every fashion editorial he’s ever been in. The confession begins. Unless it’s another performance, moving from the Lower East Side in 2015 to the Cannes film festival in 2011, Beverly Hills 90210 and the Day-Glo gaze of the Late Eighties and Early Nineties. The quality of a photograph is called into question in a culture that is oversaturated with them. The desire for image to be replaced by a different, more symbolic charge of the written text and physical utterance is a call to restore faith in art’s sustainability. Death meets birth for its eventual renewal.

In re-evaluating the genre, Campanioni also re-evaluates our cultural capital, as well as our current modes of interaction and intimacy, exploring narcissism through the lens of self-effacement, pop culture, the cult of celebrity, and the value or function of art and (lost and) found art objects.

“Campanioni’s writing has a really hypnotic rhythm. Something very Donald Antrim to this, except Donald Antrim isn’t in his twenties writing for the next generation of readers.” –The Wrong Quarterly

“Campanioni offers us references and reflections on city life, highlighting the tension between being in an environment filled with anonymous potential and the highwire act of maintaining intimacy in a world where every thought can be recorded and published for everyone to see in an instant.” – Prelude

“Campanioni’s use of question and insight and the overall humanity of this work is beautiful and impressive.” – Saw Palm

“Campanioni’s style is awesome. It’s like Bolaño meets DeLillo meets Borges, which is everything I ever want out of a reading experience.” – Red Fez

“Campanioni’s poetry is poignant and honest, possessing a sincere (if skeptical) romanticism that is necessary yet rare in the 21st Century. These poems stand the test of time.” –LIGHT/WATER

“A strong but delicate linguistic tour de force.”–Bellingham Review

Writer Chris Campanioni gives a crucial glimpse into our modern narcissism with his new book of memoir / non-fiction / hybrid text / does it really matter, Death of Art. Despite the ostentatious title, Campanioni tactfully avoids repeating oft-argued cliches regarding art’s apparent demise, and instead uses the title as an entry point for talking about identity, language, social media, and modern life as a kind of performance.

The book begins with Campanioni sitting around with a stranger cutting his face out of magazines in which he modeled. The book follows this act of self-immolation throughout, as Campanioni struggles with trying to refashion his own image and his own identity, in a world where these things are valued above all else. Campanioni is frank and open about his stints as a model and actor, and his struggles with the performative aspects of both. The text almost becomes a space where Campanioni can explore himself; a liminal space where he can avoid binaries and social norms and—in a way—deconstruct himself:

I had lately been thinking of a project titled Death of Art, which itself came from the blacked out title of a poem I’d just written called ‘Death of the Artist…’ Cutting out my face could be the beautiful overture.

Formally, Death of Art moves from vignette style passages of memoir, to essays and poetry. Campanioni’s tone alternates from playful, to philosophical, to the banal and the confessional, and all at a blistering pace. His subjects range from 90210 and Tinder dates, to social media narcissism and celebrity culture. An obsession with 90210 and a brief reference to Care Bears in particular become interesting pivot points for Campanioni to make comparisons between the empathy of our former analog world, and the disconnectedness of our modern digital world.

Death of Art brilliantly taps into our insatiable need to be seen and felt via social media, and how life is not experienced in our modern age, but rather, documented. The Facebook photo as preferred cultural currency to the actual image and experience represented.

The same way that our generation will look back on our lives in sixty years and there will be plenty to see. Probably we only wish we would have lived it too.

In the section titled “Self-Interested Glimpses,” Campanioni adopts an essay style (as he frequently does) and argues that “Authentic experience has been replaced by fetishized experience; existence becomes object.” In Campanioni’s world, the Instagram photo of a sunset now reigns supreme over the actual sunset. This is not a wildly new concept, as many postmodern thinkers have believed that society and modern culture have started to place more importance on “simulacra” or the simulation of reality, rather than the object itself.

For Campanioni public spaces have become zones of anti-social behavior. He argues that the increased access to each other that social media provides us has “led us to become less tolerant, less sympathetic, and less understanding.” This is exemplified in the book via the nearly tweet sized entries describing a series of Tinder dates where he struggles to make eye-contact and prefers to meet in coffee shops, hotel bars, or “anywhere public enough to pass through, in transit, like anyone else. Just passing through.” The Tinder passage in particular reads like a detritus of ineffectual millennial dating experiences that only work to solidify Campanioni’s belief that our ability to connect is stunted, not enhanced, by applications like Tinder.

Much of the book is devoted to Campanioni’s self-reflection and almost reads like some playful postmodern diary. The author is constantly engaged in a dissection of his own image, striving and hoping to dismantle it. “The Internet has its own idea of me, and so do its worshippers. I want to create my own idea of me. Maybe the Internet will follow.”

Campanioni’s concept of life being fetishized but not experienced, is nicely juxtaposed with passages that reflect his childhood:

We lived our days as if they were scenes in a musical; we danced & continued to sing. Sometimes in Spanish or English but also often in a language made up by my father, a practice I’d adopt too, & which became my true joy in life: the pleasure of words & the sounds they contained. Whether it meant anything was besides the point; it meant everything.

Here childhood is reflected upon nostalgically and without the author’s jaundiced view of our current culture’s unchecked narcissism. It’s also indicative of Campanioni as a great linguaphile, and the simple pleasure he derives from the physical sensation of the words exiting his mouth. This runs counter to the mechanized way we communicate now:

Face-to-face meetings have given way to my face on your touch screen…

Death of Art is a punchy hybrid text that holds its own intellectual weight and does well to not veer off into pretension nor cliche, which is no minor triumph considering it’s broad and aspirational title. Campanioni is a serious writer and a world class thinker, and there is something great to be gleaned from his latest offering that seems to revel in its ability to avoid classification and open up a dialectic about the modern ways in which we communicate. - Michael Browne

http://angelcityreview.com/death-of-art/

When Robert Rauschenberg abraded the surface of a de Kooning drawing in 1953, he did more than create a new art form. He demonstrated that art’s greatest affirmation could reside in the negation of surface. Poet, memoirist, and essayist Chris Campanioni adapts the dialectic for the age of the smartphone. For him, it’s not about the A/B binary of original object and subverted result; Campanioni brings Situationism to the party, generating texts with performative constraints that are often obscured as the writer erases his path to the final product.

The book is framed by an untitled prose opening and almost thirty pages of a section entitled “Scenes Deleted After the Release.” The eleven sections between also finger the edge of the screen—sometimes in nervous gesture—others with gleeful affirmation of the fictive. “Half of life is pretending. The other half is pretending,” Campanioni writes in the front matter, both as a spoiler and a tutorial: everything to come should be regarded with a fluidity reserved for film, music, and the other kinetic arts. Campanioni resists the fixity of self; as performer, he passes from situation to situation, from one role to another. With a fondness for 90210 and Foucault, he is Frank O’Hara traveling the hyper-connected contemporary landscape via iPhone—spawning, recording, discarding speculative versions of himself.

In “To Love and Die in L.A. (Cut It Out),” Campanioni hires a stranger off Craigslist to remove his face from every print ad in which he's appeared the past eight years. The stated objective is “The Death of Art,” an imagined project that gives the book its title. Its real goal is engaging the stranger in a dialogue about identity with the constructed self Campanioni has prepared for the occasion. In “Screen Play,” this back-story is erased, leaving a poetic frame that asks the reader to provide the emotional architecture Campanioni has removed:

& then I am

Careful to make this

Something I might

Count later

In private I suck

The minutes dry

Or try to fixing

You in my gaze

The poem registers as excerpted text messages that simulate the alienation of digital natives. Its appropriation is reminiscent of Krystal Languell (Gray Market, 1916 Press) and Ben Fama (Fantasy, Ugly Duckling Presse). Campanioni speaks sotto voce to give play to the idea that the words are the actual voice of the author, the one behind all the book’s nonstop antics. “Can’t you tell” succeeds—as do many of the poems—because it can be read both ways: as traditional poetic effusion, and as assemblage posing as traditional poetic effusion. Other poems, like “Overheard at a party,” play with the same duality while questioning why the authenticity of the words themselves shouldn't be sufficient:

Pressure problems

Problems with being broke

Or better than that, broken

& by better I mean worse

& by worse I mean haunted

Or hanging around

Never for a minute

Asking what

Really is the difference?

Campanioni’s questioning pervades every performance. “So to begin” is a story that teases inquiry into the writer’s bilingual childhood. Miniaturized descriptions of character and place are interrupted by criticism of the proceedings as imagined films and stage performances. The criticism can seem forced, but its falsity frees the author to be vulnerable about the disjointed background that was the prequel to a disjointed adult life as fashion model, teacher, and writer: “We lived our days as if they were scenes in a musical; we danced & continued to sing. Sometimes in Spanish or English but most often in a language made up by my father.”

Campanioni’s love of performative artifice accumulates throughout the book, giving the writing the glitchy surface of an early Ryan Trecartin video. While Campanioni’s work lacks the media artist’s love of lime-green face paint, it compensates with rapid cuts, odd camera angles, and an endless string of new selves—each holding a pair of scissors or other tool for deletion. He is at his most disruptive in “coming soon! (in three parts),” a poem whose thick, looping surface suggests a tagged-up 1980s NYC subway train:

pay to see

graffiti scrawled

on the front of the fun

the big drop, the hanging static

bumper cars, horses held

in place & sated

https://brooklynrail.org/2017/03/books/Adventures-in-Self-Voyeurism

This everyday anxiety of those of us trying to make it—almost making it—never really going to make it—is flawlessly illustrated in Chris Campanioni’s Death of Art, published by C&R Press. It’s not common that you read a collection of poetry or a novel that describes so well your soul and its search for significance. The soul that is sexy enough to be plastered across a billboard over the BQE, but smart enough to be published in The New Yorker. A soul so drenched in culture it doesn’t know what’s permanent or fleeting, just that it needs to be part of it. A soul that almost feels guilty for indulging and not getting creative work done on a Saturday night, and then subsequently regretful for staying in when you could have been out “making connections.” Campanioni, both a recipient of higher education and a prior soap opera star with perfectly defined muscles, fits the role and has lived the life to make such a novel come to fruition. It’s sexy. It’s smart. It’s dark. It’s real. The concept begins early on in the book and continues throughout like a punch to the face (or the gallery wall).

https://www.nomadicpress.org/reviews/deathofartcampanioni

Death of Art, 31-year-old Chris Campanioni’s memoir, is an amalgam of prose, poetry, and text messages. His name might not be familiar to you, though he’s appeared in commercials, numerous print ads and occasional acting gigs. If you look for Campanioni’s photo at the end of the book you’ll be disappointed. But fear not, there are plenty of pictures of him on the internet. Among his writing credits, Campanioni’s 2014 novel Going Down won the International Latino Book Award for Best First Book, and a year earlier he won the Academy of American Poets Prize. He teaches literature and creative writing at Baruch College and Pace University, and interdisciplinary studies at John Jay.

The majority of Death of Art centers on his adult life, but here’s a taste of his happy early years:

We lived all of us together in a big room with a kitchen where my mother would cook & my brother & I would dance & chant, shaking a line around the table, waiting for my father to arrive & clapping when he did. [ . . . ] My mother wipes her hands on her smock & turns around to catch his gaze. The stove hums & the red rice cooker calls out to the black beans, the wooden spoon in the steel pot, the supper that awaits.

We skip to adulthood in an expressive piece called “Self-Interested Glimpses”:

I had thought that working as a model had transformed time into a circle, a cyclical exchange of repetition and recurrence. The only days that made any sense to me any longer were today and tomorrow. Everything else felt impossible to keep track of [ . . . ] But it wasn’t just my experience in the fashion industry that had changed time; it was also our culture, the technological processes we’d adopted. [ . . . ] Time as it is represented in the world of images—Selfies, Snapchats, Vines, and countless other self-interested glimpses—is instantaneous and fleeting. Quickly forgotten.

He goes on to say that the “last decade of my life has been filmed, photographed, streamed, and sold back to mass culture. I get paid for it but it isn’t just me who’s doing the buying and selling. It is all of us; it is all of our lives. [ . . . ] We are selling ourselves back to ourselves.”

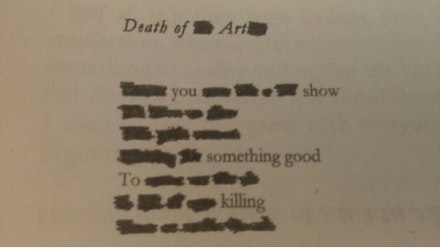

The book carries a nice rhythm by interspersing poems among short essays. You could even read pages at random and not lose any of the effect. Campanioni explains the title of his book, saying it comes from “the blacked out title of a poem I’d just written called ‘Death of the Artist.’” The original poem begins:

I want you now like a TV show

It’s been so slow

This pilot season

Waiting for something good

To come on the air

Is full of eyes killing

Time [ . . . ]

The blacked out version is found after the Acknowledgements page, which normally closes off the book, but in Death of Art, additional writings follow the acknowledgements, and you don’t want to miss them.

I found that Campanioni’s essays often contain poetic passages, as when he’s talking with his agent: “[ . . . ] I tell her about the memoir I’d like her to sell. [ . . . ] Everything’s a question for something else. Don’t sell yourself, I tell myself in silence. Don’t sell yourself short, my agent tells me, except she is speaking out loud.”

And I’m unable to classify which genre several pages titled “50 First Dates (a Tinder story)” falls into, but it’s pretty amusing. Example: “My first questions usually involve music. And if they like Taylor Swift, I bury my head in the menu. And if they call her ‘T Swift,’ I go to the bathroom and never come back.”

I was drawn to the essay titled “The Nose” because instead of riffing on Nikolay Gogol’s short story of the same name, it involves a woman he calls The Nose because she creates scents in the fragrance business.

When I finished the book, I wondered how much I actually learned about Campanioni’s life. Bits and pieces stick in my mind, such as his girlfriend is named Lauren, he’s a big 90210 fan, he doesn’t shower very often, is well traveled, has a brother named John, and he gets recognized on the street a lot. I came away with mixed messages about his views on modeling and acting, but it’s pretty clear he likes teaching and loves to write.

Death of Art can be read as sheer entertainment or, with more concentration, a summary of Campanioni’s life and thoughts so far. I think he’ll have a whole lot more to say in the future, so watch for more. - Valerie Wieland

https://www.newpages.com/book-reviews/death-of-art

From the cover: “Death of Art dissects post-capitalist, post-Internet, post-death culture; our ability and affinity to be both disembodied and tethered to technology, allowing us to be in several places at once and nowhere at all.”

Identity, Tinder, family, celebrity, Brooklyn: nothing is off-limits in Campanioni’s essays as he talks about growing up with hurricanes (“Storm Season”), being told not to get too tan lest he look too Latino to get cast in something (“Self-Interested Glimpses”), and looking at modern life through the lens of someone who identifies as an “artist.” As Campanioni continually questions his own journey, so the reader questions their own.

Campanioni is a meandering, unreliable narrator who facilitates the reader’s journey down the rabbit hole of his prose at breakneck, forgetting-to-breathe speed: you can’t wait to feel the ground under your feet again. He lets go of your hand before an unlit set of steps and lets you stumble as you feel inexplicably guilty about the Instagram notification that draws your attention away from the page. As Campanioni questions himself, it’s everything you don’t really want to hear. He takes the cliché of “Who am I?” and massages it into “Who am I pretending to be? Who am I as an artist in a world that seems to be waging a war on art? What even is art anymore? What is identity anymore?”

“Who hasn’t ever asked themselves: Am I a monster?

Who hasn’t ever asked themselves: Or is this what it feels like for everyone?”

The collection is marked by Campanioni’s signature mastery of the line, shameless sensuality, and abiding love of 90210. By the end of Death of Art, you feel like you have read something terribly important. You can’t seem to pin down why it’s sitting so heavy in your belly, or even the specific words that so moved you, but you know you can’t continue to move through the world the way you have been; you know something has to change. - Catherine Chambers

http://www.duendeliterary.org/duende-blog/2016/3/26/a-review-of-death-of-art-by-chris-campanioni

Chris Campanioni, Tourist Trap, Black Rose Writing, 2015.

In suburban New Jersey, in the summer of 2006, a recent college graduate answers a Help Wanted ad from a travel agency seeking tourists for "direct sales distribution." It doesn't take him long to figure out the function of the company-issued camera. During an initial trip to London, he also discovers his real role: Terrorist. Instead of fleeing, he quickly finds himself swept up in a cast of characters from New York City's fashion and art world, the newsroom and the travel industry, government agencies and back alley dentists, all of them involved in the culture industry and its destruction of social and historical landmarks and signposts for money-and later, for something much greater than currency. From the south of France to Thailand and North Korea, the thread runs deeper, and as readers learn more about the culture industry, they also learn that no one is inculpable, and nothing is truly as it seems.

And no goddamn Facebook flag graphic will fix any of it. - Jonathan Marcantoni

Chris Campanioni, Once in a Lifetime, Berkeley Press, 2014.

This is a joint publication of Floricanto and Berkeley Presses. Fifty poems and one day provide the footage for Chris Campanioni's Once in a Lifetime (a film in four acts). But even time gradually dissolves in this coming-of-age drama interlaced with pop music, the age of Internet and status updates, cinema and celebrity, memories of Cuba and Poland, and the passage to the United States. Runtime: 24 hours.

"Campanioni captures in revelatory verse and musings, the solemnity at the crossroads of desire and reality. He reveals, in the span of a day that stretches years, continents, and cultures, the weight of his immigrant parents' expectations for a better life wrestling with his own expectations of artistic transcendence. His story reveals a struggle for relevancy in the anonymous, endless streets of New York, a city whose immigrant past mirrors the author's own. This day in the life finds Campanioni striving, through his art, through his relationships, through his tri-lingual worldview, to be a worthy successor to the brave men and women who fought to make his life a reality. Instead of fighting his fragmented identity, Campanioni's Once in a Lifetime embraces and celebrates his role as a universal man." - Jonathan Marcantoni

"Chris Campanioni takes you down the alleys and arteries and sugary retail aisles of your lifetime. He has captured a moment between our machine world and our humanity, telescoping the grandeur of existence into one finite day--like a moment that changed how you saw the world, or a good dream. Recommended."Mike Joyce

Chris Campanioni’s 2014 poetry collection, Once in a Lifetime (Berkeley Press), is a day-in-the-life narrative in poetic form. We have the immigrant parents, the lost son, the doomed romance, the painful realizations that accompany maturity, and the reinvention of self, played out over the course of 24 hours (and possibly including dreams as well). In narrative form, the American dream plotline would have seemed cliché or at the very least, common, but by putting this story in poetic form Campanioni has revitalized the genre by unearthing the universal yearning for home and the melancholy that informs such a desire.

The story Campanioni is telling is his own, or better put, a variation on his perception of the world as he has lived it. In his other works, Campanioni’s characters share a remoteness from the societies they live in. The gap between perception and reality, between public and private masks, between intention and outcome are obsessions of his art, and here he turns his focus on his parents, who really are immigrants: a Cuban father and a Polish mother, both of whom fled to the U.S. to escape Communist governments. There is a sharp contrast throughout the book that portrays the roots of suffering his parents share and the mundanity of his own. While suffering brought his parents together and allowed them to forge a lasting partnership and strong family, Campanioni (or his character) can only share the small, seemingly insignificant details of life with another person. His acute awareness of the subtlest beauty and humor of the world, however, proves to be a barrier to intimacy. Without a grand narrative of his own, the Campanioni of the book must find another way to connect, and as mentioned in the above poem, that means going “home”, which is to say, it means finding a new way of connecting his parent’s narrative with his own.

The story of Once in a Lifetime is not confined to the internal desire for home, but also to the physical surroundings that make that home. The morning and evening sections of the work are deliberately urban and tied to technology. The first poems are all ruminations on the vast cityscape and the sense of isolation one feels in the middle of a crowd.

“Impossible to draw to scale

Conversions or conversations

Overhead musings, overheard

Talk from the countertop

Of a café you’ve never been to

Before, or any place with people”

– From Cold Open

“Facing the empty

And ornate room

A chandelier

A polished bar

Two paintings

Faces to freeze like that

Remembering the whole time

Something as soft

As the quiche

On my plate”

– From Motionless at a red booth

At all times, Campanioni is one step removed from these places and things, which inform where he is but not who he is. One of the most compelling aspects of the book, especially in comparison to Campanioni’s previous poetry collection, In Conversation, is that the first mention of technology is not as a barrier, not a continuation of the common social criticism that people nowadays would rather stare at their phones than have a conversation, but rather as a bonding experience between Campanioni and his parents:

“My father learned English

On the radio—

Sing-song Santiago Spanish

“Rocks Off,”

The Rolling Stones

Your mouth don’t move

But I can hear you speak

So many questions

People want to know

What makes me what I am

I tell them way I was raised

I tell them

Ga-ga-BOOM

Ga-ga-BOOM

Music everywhere in the house”

– From Talk Talk

Technology is a unifier, a source of joy and nostalgia, and perhaps it is significant the tech being referred to is in the past. As though somewhere between childhood and adulthood, something has been lost, or perverted, to make this generation feel isolated by the very things that should have made connection easier than at any time in human history.

What is largely absent in the beginning and ending sections is nature. The descriptions are focused on the man-made, whether they be buildings or other humans, it is only when the narrator sets off with a lover on a road trip down south, in the afternoon section, that the natural world encroaches on us. Urban life can be so all-encompassing as to make the world itself surreal. In Juan José Saer’s masterpiece El entenado, the book begins with the main character expressing his preference for the city over the countryside, “Más de una vez me sentí diminuto bajo ese azul dilatado: en la playa amarilla, éramos como hormigas en el centro de un desierto. Y si ahora que soy un viejo paso mis días en las ciudades, es porque en ellas la vida es horizontal, porque las ciudades disimulan el cielo” (More than once I felt diminutive beneath that expansive blue sky: on the yellow beaches, we were like ants in the middle of the desert. And now that I am an old man, if I spend my days in cities, it is because here life is horizontal, it is because cities shrink the sky).

Campanioni’s narrator does seem to shrink in this section, the elements engulfing him, especially water. As he yearns for his lover’s embrace and the warmth he felt as a child, the waters rise, the waters reflect, the waters consume, but he is never able to give himself over. The relationship strains, his sense of space and time strain, and the woods and lakes of the Deep South grow in prominence until he drowns in his uncertainty.

At this point, the book looks inward, and this brings us back to the narrator making his final journey home. To learn about life, not as he believed it should be, but as it is, a series of struggle and sacrifice, of remorse and forgiveness, of lacking and overflowing: of food, of material items, of options, of money, of love.

Life is an ever-emptying shell, that is, like a hollow object at sea it is constantly filling with water, the bringer of life, and then emptying it out. In between is hollowness, which some may see as death; the shell remains, its existence continues as it awaits the next wave of activity. Every wave, in entering the shell, is informed by what came before, particulates of past surges, scars as well as smoothing of the frame, and as the water leaves it carries those experiences as it breathes new life to the shoreline, only to retreat. Life and death are always present simultaneously, triumph becomes suffering which becomes triumph once again. To place importance only on the suffering is to ignore the great beauty of success, and to only focus on success blinds one to the lessons of tragedy. This exchange occurs again and again, and this is the legacy of generations, the traces of our daily life. So we close with this mediation on time and what our perception of it says about us:

“Time stretches like a rubber band

It stops, it starts, it lengthens

Each time a voice

Track clicks in

Hours pass

A minute or two

Goes by, unless I am

Sitting here

Surrounded and alone

Making time

Stop myself

Making it assume

An untangled ribbon

Of hair, glancing

At my phone, too

Wondering when

The moment will arrive

A slight pause, not a full stop

Not even

A semicolon, more like

An interruption or interference

CAUTION

To consumers

This image is enlarged

To show detail

Blow-up

Cortázar/Antonioni

Another unsuspecting death

Under red light

In the dark room

Now the city moves

Like a map you are drawing

A sinking feeling (I’ve been here before)

Faulty reception, static

Other people’s memories

Images I only recognize

On TV, old films, faces I’ve never seen

A quick shift in the hips

And you’re looking out

Through someone else’s eyes

It’s such a bore

To be one person

All the time”

– From Fashion of the Seasons

Campanioni’s Once in a Lifetime is a mirror that moves closer and closer to us, making us dissect the tiniest detail of ourselves through the author’s journey. In the end it asks, now that you know who you are, will you stare it in the face fearlessly, or will you blink? - Jonathan Marcantoni

minorliteratures.com/2015/11/04/once-in-a-lifetime-by-chris-campanioni-jonathan-marcantoni/

Interviews:

The Brooklyn Rail (March 7, 2019)

Beyond Metaphor: On Prose by Chris Campanioni & Elizabeth Powell

Latina Book Club (February 14, 2019)

Here is the Love: Interview with author Chris Campanioni

Kenyon Review (January 17, 2019)

“What’s at stake is the production of knowledge”: a conversation with Chris Campanioni

Poetry Foundation (January 10, 2019)

Poetry Foundation

Big Other (January 2, 2019)

Most Anticipated Small Press Books of 2019

Dead End Follies (December 13, 2018)

Notable Reads of 2018

Hypertext Magazine (September 28, 2018)

Interview with Chris Campanioni

minor literature[s] (January 22, 2018)

“Homage and criticism are really two sides to the same mirror”

The Los Angeles Review of Books (September 2, 2017)

Name Dropping: An Interview with Chris Campanioni

Sinkhole (June 21, 2017)

Interview with Editor Chris Campanioni

ENTROPY (January 31, 2017)

PANK Books Interview with Co-Editor Chris Campanioni

Nomadic Press (September 21, 2016)

Talking Paper Interview Series: Chris Campanioni

The Brooklyn Rail (May 3, 2016)

Reframing the Death of Art

TED Talks (March 23, 2016)

TEDx Presents: Living In Between

Latino Rebels (September 2, 2015)

Interview with Prize-Winning Author Chris Campanioni

RealClear (December 9, 2013)

The Model Writer

LatinaLibations (May 30, 2013)

Interview with Author Chris Campanioni

Freshpair (April 26, 2013)

Proving that an underwear model can be more than one dimension

Texts:

The Operating System (NaPoMo 2019)

Chris Campanioni on Walter Benjamin

Redivider (16.1)

Time Piles Up Presses In & Flattens

Abridged (0_56 Alt)money/shot

Im@go: A Journal of the Social Imaginary (12)

Fixing Being with Likeness: Facial Recognition as the Stage for Global Per-Formance

The Florida Review (42.2, 2018)

mortadella on the street corner

IC La Revista Científica de Información y Comunicación (15: When Memories Take a Stand)

Letters From Santiago: Re-membering the Displaced Body Through Dreams

Hobart

Two poems

M/C: Media and Culture (21.5: The Nineties)

How Bizarre: The Glitch of the Nineties as a Fantasy of New Authorship

Abridged (0_52 Contagion)

scene (& not scene)

Entropy (Under the Influence #5)

The Literary Psyche

Interações: Sociedade e as Novas Modernidades (Volume 34)

Digital (In)Visibilities & Inequalities

The New Engagement (Issue 15)

Three noteboook excerpts from MS DOS

Hypertext Magazine

Excerpt from DRIFT

Supernatural Studies (Issue 4.2)

How Do I Look? Data’s Death Drive & our Black Mirrored Reflections

X-RAY Literary Magazine (Issue 9)

Born Under Punches

Poetry International

A Collaborative Poem

Paris Lit Up (No. 5)

See What Happens When These Naughty School Girls Stay After Class For Detention

GlitterMOB (Issue 10)

Truckstop Fantasy Number One

Cosmonauts Avenue (January 2018)

Manufactured Pleasures

Origins Journal

Two notebook entries

Chróma Magazine (The Red Issue)

S-O R

Stat(R)Rec

Three poems

The Normal School (Volume 10, Issue 2)

Two poems

Palimpsest (No. 8, Fall 2017)

Missing Letters

Wisconsin Review (Volume 50, Issue 1)

I grew up always out

fluland

Four poems

A VOID (1)

Two Frieze Frames

Five2One (16)

Five Frieze Frames

Quiet Lunch (Book 4)

In the beginning was the word, & the word

Duende (Exodus Feature Spring 17)

Nobody

HVTN (3.1)

Three poems

3:AM Magazine (April 12, 2017)

Ghost in the Machine

Whitehot Magazine

I went to the Whitney Biennial & all I got was this poem (Portrait of An-Other Portrait)

The Right To Carry (Our Rapidly Expanding Company)

Gorse (Issue 7)

4 Poems

White Wall Review (Issue 40)

Now & Laters

Petrichor (Issue 3)

Four hybrid pieces

Glass: A Journal of Poetry (November 16, 2016)

Donald Trump Shakes

DIAGRAM (16.5)

5 Erasures

Hotel

Two poems from Irregular Accounting

Hypertext Magazine

Time, and Time Again

Bellingham Review (Issue 73)

Let’s meet at the beginning of water

Yemassee (Issue 23.2)

Privileged/Witness

Funhouse Magazine

Casual Encounters

Connotation Press (September 2016)

Five poems and an interview

Reality Beach (Issue 3)

I arrive as I always do

Entropy

Hot Tips For Healthy Living

Notre Dame Review (Issue 42)

In a place where everybody

Tahoma Literary Review (Issue 7)

I do

London Journal of Fiction (Issue 2)

Buffering

Ambit (Issue 225)

Ash Wednesday

America is Not the World

Paul Walker’s dead (a love story)

Articulated Press Anthology

Excerpt from DEATH OF ART

Public Pool

Two poems

The Opiate

The World Writes Itself/One of these things is not like the other

Those That This (Issue 10)

Two poems

The Matador Review (Summer 2016)

Three flashes

DIAGRAM (Issue 16.3)

Adaptation

Atticus Review

“Yes we’re open” extended prose section

Queen Mob’s Tea House

Drinking five dollar tap water at a club

LiGHT / WATER (Issue 1)

Two poems

3:AM Magazine (June 8, 2016)

Art Is For Necrophiliacs (If that’s how you spend)

Entropy (Enclave)

Two #finalpoems from Chris Campanioni

At Large Magazine

Lamborghini’s bid for change is a continuing legacy

Being Our Real Selves Online Starts By Augmenting Reality

We’re Sorry, We Could Not Locate the Server

Faraday Future’s Vision is Shared

Lost In Ferrari

Two essays

Casco Viejo/The Passenger

Hot Pursuit

Who The Hell Are You

Flippy Is Your Starring Role

Smoking Section

Living In Between