Christine Wunnicke, The Fox and Dr. Shimamura, Trans. by Philip Boehm, New Directions, 2019.

Excerpt

A delicious mix of East and West, of wonder and irony, The Fox and Dr. Shimamura is a most curious novel

The Fox and Dr. Shimamura toothsomely encompasses Japan and Europe, memory and actuality, fox-possession myths and psychiatric mythmaking. The novel begins near the story’s end, in Dr. Shimamura’s retirement. A feverish invalid, he’s watched over by four women: his wife, his mother, his mother-in- law, and a nurse (originally one of his psychiatric patients). His mother is busily writing and rewriting his biography, Between Genius and Madness.

As an outstanding young Japanese medical student at the end of the nineteenth century, Dr. Shimamura is sent―to his dismay―to the provinces: he is asked to cure scores of young women of an epidemic of fox possession. He considers the assignment a joke, believing it’s all a hoax, until he sees a fox moving under the skin of a beauty. He comes to believe not just in fox possession, but also that he in fact “cured” the young woman with a kiss, by breathing in the fox demon (the root of his lifelong fever).

Next he travels to Europe and works with such luminaries as Charcot, Breuer and (briefly) Freud himself (whose methods he concludes are incompatible with Japanese politeness). The ironic parallels between Charcot’s hack theories of female “hysteria” and Japanese ancient folklore―when it comes to beautiful writhing young women―are handled with a lightly sardonic touch by Christine Wunnicke, whose flavor-packed language is a delight.

Tyler Goldman and Christine Wunnicke: “The Imperfect Enjoyment” of Translating the Scandalous

An elusive little novel about medicine, memory, and fox possession

Dr. Shun’ichi Shimamura, a young physician, is sent to the provinces to treat the scores of young women who appear to be suffering from fox possession. Shimamura, a bright, ambitious student, is flummoxed by the assignment: Why give credence to a superstitious belief out of Japanese folklore? It’s summer, it’s hot out, and all the young women turn out to have only “the most annoying diseases (dipsomania, cretinism, an ovarian abscess…).” But then Shimamura comes to the last patient. As he examines her, she begins to writhe and convulse; Shimamura can plainly see, moving beneath her skin, a fox. German writer Wunnicke’s (Missouri, 2010) second novel to appear in English is a marvel, a wonder—and deeply strange. After his fox excursions, Dr. Shimamura sets off to study in Europe. In Paris, he becomes acquainted with Dr. Charcot and his dubious work on hypnosis and hysteria. When afflicted, Charcot’s female patients—he parades them around in front of a lecture hall—bear a remarkable resemblance to the woman who’d been possessed by a fox. Oddly, in the midst of all this, Shimamura’s memory seems to be fading—particularly his memory of one crucial night with that last fox-possessed patient. In any case he goes on to meet other masters of early neurology and psychiatry (Freud and Breuer each make an appearance) before returning home. Ultimately Shimamura retires to a remote area where he waits for death. It is from this standpoint—a few decades after his European sojourn—that the rest of the novel is narrated. Shimamura is cared for by his wife, his mother, his wife’s mother, and a housemaid—no one can remember whether the housemaid was once a nurse or a patient herself. Gradually it emerges that Shimamura’s wife may be tampering with his memory, conducting little experiments of her own. What is real and what isn’t? What is superstition, what is medicine? Wunnicke’s sly novel offers a great deal of mystery and humor but no hard answers.

With her delicate prose, arch tone, and mischievous storytelling, Wunnicke proves herself a master of the form. - Kirkus Reviews

Wunnicke (Missouri) spoofs the misogynist history of psychology in this clever and rewarding novel of slippery memories tinged with Japanese myths. In the novel’s frame, retired Japanese neurologist Shun’ichi Shimamura is ailing from consumption, watched over by his mother, his wife, her mother, and a maid, who was either a nurse or a former patient. As a new doctor in 1891, Shimamura traveled the countryside in search of women afflicted by a folkloric fox possession. After many false reports, a genuine case shakes Shimamura and becomes even stranger when his annoyingly eager young traveling companion goes missing, and the fox transfers into Shimamura’s body. Hiding his constant fevers and mysteriously sudden allure to women, Shimamura travels to Europe on an imperial government stipend to study neurological disorders. He first goes to France where language barriers frustrate him, and then to Germany, acting as both research assistant and unwitting subject of study, as a male neurotic, for famous pioneers of psychology, including Jean-Martin Charcot and Josef Breuer. In his later years, Shimamura’s own hazy recollections and the interference of his household make for a complicated puzzle about the reliability of the narration. This gracefully amusing blend of history and imagination will beguile readers keen on questionable narrators and magical realism. - Publishers Weekly

German author Christine Wunnicke’s latest novel to appear in English, The Fox and Dr. Shimamura, is a mythical, mystical, and at times bizarre tale of a late nineteenth-century Japanese doctor who is sent to remote areas of the Shimane prefecture to cure women of fox possession. The book begins at the end, as Dr. Shimamura’s career as a renowned neurologist has passed, and his memories of curing fox possession and other forms of female hysteria are told in a feverish state from his sick bed. His hazy memories also bring us through his time in Europe, where he meets and studies with other famous doctors, Charcot and Breuer, who have an interest in ailments that particularly affect females.

Wunnicke’s fractured narrative alternates abruptly between the doctor’s past and present, a symptom of her narrator’s poor state. The author routinely reminds us throughout that her narrator is not a reliable one. First Shimamura tries to recall as many details as possible about the time he is sent by the Imperial University in Tokyo to investigate stories of women possessed by foxes. Each attempt at summoning details of past trips concludes with a remark from Wunnicke along the lines of, “Shimamura’s brain manufactured many memories he couldn’t place.”

As he travels—or remembers traveling—through the remote countryside with his talkative and half-naked teenage assistant, he doesn’t, at first, encounter any women who appear to be possessed by foxes, but instead he comes across diseases that are typical of poor rural women: tuberculosis, meningitis, and flu. While nearing the end of his journey, the doctor meets a beautiful young Japanese girl who displays signs of hysteria, and who seems to have a fox living under her skin:

While at rest the animal evidently resided right below Kiyo’s underwraps—at least that was where he seemed to be working his way out. It was a small fox, two or three hand lengths, depending on whether he was stretched out of balled up, and in his cramped quarters just under Kiyo’s tender white skin he moved a bit like a caterpillar. Kiyo traced his movements with her finger: across her stomach slowly up into her chest, into her right armpit and then the left and then with a jerk into her left upper arm, where the creature pushed nearly all the say to her elbow, until this swelled and swelled to the point of bursting.

While we are never quite sure what is real and what is a figment of Shimamura’s fevered memory, we can look to Japanese mythology and literature for clues as to Wunnicke’s purpose in representing women possessed by foxes. In his free time, the doctor himself researches this very subject with zeal; he becomes an expert on the Japanese deity Inari, and even founds a Society for the Study of Myths.

Inari is depicted in many forms in Japanese myth. One includes a white fox with nine tails, though this shape-shifting spirit is represented at times as a spider or a dragon. One of the most intriguing aspects of this myth, as it relates to Wunnicke’s story, is the fact that this god can be male or female; its gender is always fluid. The dual gender of Inari becomes reflected in the character of Dr. Shimamura himself, who, after treating his fox-possessed patients, also seems to take on this “female” ailment himself. After he cures Kiymo, he too displays symptoms of hysteria, which include fevers, fainting, and lapses in memory. In addition, the doctor appears to have gained a special sympathy for women who recognize him for his compassion, and who begin flocking to him in droves.

The story grows even more surreal as Dr. Shimamura tries to recall his time spent with other prominent physicians of the day in France and Germany. With this East-West connection, Wunnicke seems to be making the point, while simultaneously mocking the misogynist idea that, although they are described in different terms, it is believed in both Asia and Europe that women’s health and states of mind are affected by their physiology. In the West, the idea that women are prone to diseases that induce hysteria can be traced back thousands of years to Ancient Greece. The word “hysteria” comes from the Ancient Greek word ὑστέρα, which is the word for “womb.”

According to the Hippocratic Corpus, the Ancient Greeks believed that a woman’s womb was not located in one place, but moved around her body and, depending on which part of her body the womb occupied, she would display symptoms of depression, anger, madness, or any number of irrational behaviors. In order for a woman to be cured of her hysteria, this “wandering uterus” had to be contained. The Ancient Greek speculation about the “wandering uterus” is eerily similar to Wunnicke’s description of Shimamura’s patient with a fox wandering around parts of her body.

While in Paris, Shimamura witnesses Dr. Charcot parade women in from of an audience so he can demonstrate symptoms of what he calls Grande Hysterie. What the Japanese doctor witnesses in European medicine seems strange and sad to him, all the more so because Japanese custom dictates that such illnesses are to be kept private. He repeatedly observes, with discomfort and horror, Charcot’s very public examinations of his female patients:

Nurses removed parts of the patients’ dresses to expose the hysterogenic zones, which seemed to encompass practically the entire female body, and at that time were still awaiting systemization. These zones were then observed by everyone and manipulated by one assistant or the other. There were patients who could be stuck in the arm or neck with a long needle so that it came out the other end and they didn’t feel a thing. Others might fall into a state, start twitching or even present with paralysis as soon as their stomach or should blade or finger was grazed with nothing but a feather. Assistants used grease pencils to mark the zones in question with lines and circles.

When Dr. Shimamura arrives in Germany, he also studies with Dr. Breuer, an early pioneer in the field of psychology who is mentored by Freud himself. Of all the doctors described in the text, Freud is treated by the author with the most mockery and disdain. Freud is called a “gossip monger” by his Japanese colleague and when Dr. Shimamura is about to return home he remarks about Freud’s methods, “‘The analytic conversation as a healing method for traumatic hysteria,’ he wrote to the imperial commission, ‘is of little use for Japan, as it contradicts our sense of politeness, and besides it takes too long.’”

Finally, Wunnicke slyly reminds us that, although women are powerless, even when it comes to treating their own illnesses, they find ways to quietly assert their will over men. Dr. Shimamura lives with his wife, to whom he is married through arrangement, as well as his mother, mother-in-law, and a nurse who is a former patient. The sole occupation of these women is to nurse and take care of the doctor as he suffers from consumption. But we slowly realize that they have much more influence over him—and over their own lives—than it first appears. They play mind games on Shimamura, and decide that the best way to keep him alive is to agitate him. One of the funniest scenes in the book involves a conversation they have over tea in which they flaunt their knowledge about where the doctor hides his secret possessions, which they steal and replace on a regular basis.

Philip Boehm, who is used to tackling unconventional and complicated narratives with the likes of Franz Kafka, Ingeborg Bachmann, and Herta Müller, is the ideal translator for Wunnicke’s story. Something of Boehm’s background as a stage director seems to sneak through his smooth and deft translation, especially the more melodramatic scenes, such as those Shimamura experiences in Europe. Boehm’s rendering is so natural that one oftentimes forgets that it is, after all, a translation from the German.

Wunnicke ends her narrative on a puzzling note. Shimamura is reminded of his past when two visitors, whom at first he doesn’t recognize, pay him a visit. Their recollections of his time in the Shimane Prefecture are very different than his own. What was real and what was a result of his addled memory? What is real medicine and what is myth? And how much control and influence have women really had on Dr. Shimamura’s life and career? - Melissa Beck

http://www.musicandliterature.org/reviews/2019/3/27/christine-wunnickes-the-fox-and-dr-shimamura

The Dr. Shimamura who is the central figure in Christine Wunnicke's novel is an historical figure -- Shimamura Shun'ichi (島邨俊一), who lived 1862 to 1923 and was leading figure of early Japanese neurology. The novel begins near the end of his life, in 1922, but moves back and forth between earlier experiences and the last years of his life, spent in a long and withdrawn retirement surrounded by and attended to by four women: his wife, Sachiko, the daughter of his mentor; her mother, Yukiko; his own mother, Hanako; and a maidservant, Sei -- whom he: "sometimes called Anna but more often Luise" (and who he had brought with him when he retired from the Kyoto asylum he had headed, "as kind of a memento, and because no one there knew for sure whether she was a patient or one of the nurses").

It's a strange household of slow decline -- Shimamura's clothes, like everything else, slowly wearing out -- and rituals -- like a bucket of water brought to him daily, whose purpose he doesn't understand.

Shimamura's mother has been working on writing a biography of sorts of her son for years -- originally planned as a Festschrift that had since:

Meanwhile, Sachiko -- though already thinking ahead to life after her husband has died -- plays her own little tricks to keep him off-balance, switching out a collection of toys that Shimamura keeps (obviously not very well) hidden, her reasoning being, as she explains:

As a medical professional, Shimamura gained quite a reputation, but he doesn't take great pride in it, "annoyed at being known solely for psychiatric wall padding and a collection of fox woodcuts". The wall padding was a useful innovation in asylums where patients could hurt themselves on hard surfaces; the woodcuts were a reminder of the pivotal events in his life. First off, there was a trip he was sent on by his mentor and future father in law in 1891, to Shimane Prefecture, to investigate women who were believed to be possessed by a fox-spirit -- presumably a variation on what was psychologically considered 'hysteria' in those times. Shimamura traveled to Shimane with a young student from a wealthy family who was to act as his assistant and photographer. It long seems a waste -- "There was no lack of foxes, but none of the patients displayed neurological symptoms [...] Most of the people had nothing wrong with them" -- and wears Shimamura down, so that his: "own condition had grown into full-blown neuro-asthenia, and his dyspepsia had become so explosive that for one whole day he thought he'd contracted cholera".

Only at the end of the trip is he pointed to: "Our celebrity. Your reward. The fox princess of Shimane", a more convincing case of fox-spirit-possession, which certainly has an effect on Shimamura. The daily log he otherwise faithfully kept remains blank for the two and half weeks spent with the patient, and at the end, as his mother puts it in her manuscript: "he returned to Tokyo a broken man", traumatized by, among other things, the disappearance of his assistant, who is assumed to have fallen to his death off a cliff.

Three years later, Shimamura gets the opportunity to go to Europe, and he meets and studies with some of the early masters of the field -- notably Jean-Martin Charcot, in Paris, and Josef Breuer (of Anna O.-case fame) in Vienna. Cultural differences prevent much meeting of minds -- with hurdles at every level, beginning with the linguistic one: Shimamura struggles to communicate in France, while even his fluent German puzzles Breuer: "His German was perfect and at the same time sounded completely Japanese". Similarly, the diagnoses and treatment of patients differs, with Shimamura amazed in Charcot's Salpêtrière-asylum by the (all female) patients:

Living out his retirement in withdrawn isolation -- aside from the four women around him -- Shimamura does get one more shock to the system in the novel's concluding turn, a visitor from the past whom he at first can not place, but whose appearance and story fundamentally shift the underpinnings of so much of his own life.

The Fox and Dr. Shimamura is a novel about mind-games and states of mind, including their interpretations of reality -- mental health, in its broadest form, with the experts in the field when it was at its most wide-open(-to-interpretation) trying to offer different ways of understanding (it). Shimamura's is a story of shaping -- and repeatedly re-shaping -- a life story, in retrospect: much as, late in life, the good doctor is: "annoyed at being known solely for psychiatric wall padding and a collection of fox woodcuts", he can get no better grasp on his own past himself, even as he constantly struggles to come to terms with it. Typically, when he tries to relate his experiences to Breuer: "the words 'I don't remember' made frequent appearances", while the biography his mother writes (and which he stealthily read) is one that is constantly being rewritten, changing the story; typically, the most pivotal event in his life -- the two and half weeks with the patient in Shimane -- is the one period in which his notebooks remain blank.

Change and re-construction (which includes re-interpretation) are constants in the novel, like the Shinto practice of tearing down shrines and building them anew, from Sachiko's replacing small artefacts with similar ones to keep him on his toes to Hanako's book, to Shimamura's own notebooks, which he ultimately consigns to the flames. (And, of course, Wunnicke's novel is itself a reconstruction of this actual life, based on the limited sources available to her -- based partially on fact, but just as much a creation of the mind (i.e. imagination).)

The fog of uncertainty that seems to fully envelope Dr. Shimamura -- he doesn't even know (and can't even settle on) the name of the maid (or be certain whether she was a patient at one time) -- is effective, but of course also clouds the narrative as a whole; Wunnicke can never allow Shimamura the clarity that occasionally suggests itself, in Europe or with the visitor he receives towards the end of his life ("Who was that ?" he asks his wife after his guests have left, the enormity of it too much for him to handle).

It makes for an appealingly haunting novel, slightly off-kilter, suggesting the unknown and the unknowable -- and neatly contrasting a familiar period and understanding of psychology (Shimamura's European experiences) with a much less familiar Japanese world. But even as the fox-spirits may seem typically (and exotically) Japanese, they are also only another variation of the 'hysteria' that Shimamura's European counterparts were exploring at that time.

The Fox and Dr. Shimamura is an enjoyable little novel -- helped by an occasionally wicked sense of humor (Sachiko, in particular, is an inspired creation) -- but also feels like it bites off more than it can chew, the danger, in particular, of referring to and relying on well-known real life figures certainly coming to the fore here (and that's even with keeping Freud more or less at a distance ...). If not entirely a success, it nevertheless has considerable appeal. - M.A.Orthofer

http://www.complete-review.com/reviews/moddeut/wunnickec.htm

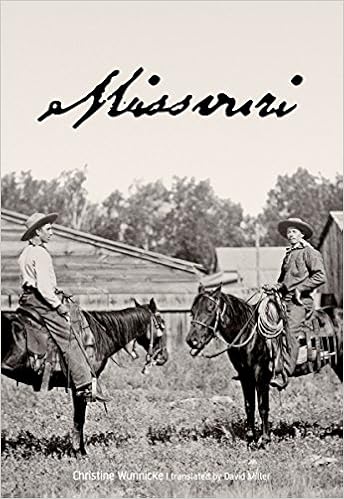

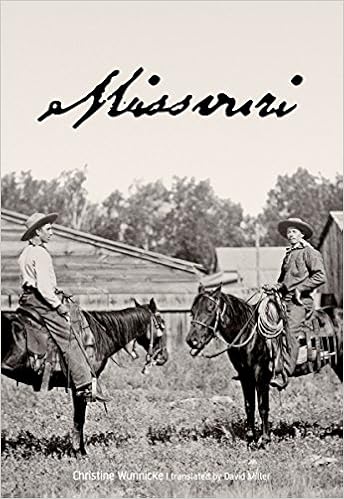

Christine Wunnicke, Missouri, Trans. by David Miller, Arsenal Pulp Press, 2010.

This earnest, violent, yet utterly transfixing gay love story is set in the nineteenth-century American Midwest. Douglas Fortescue is a successful poet who flees England for America following a scandal; Joshua Jenkins is a feral young outlaw who was taught how to shoot a man at age six. The two men meet when Joshua robs Douglas’ carriage and takes him hostage; soon, a remarkable secret is revealed, and these two very different men grow closer, even as Douglas’ brother tries to “save” him from his uncivilized surroundings

The Dr. Shimamura who is the central figure in Christine Wunnicke's novel is an historical figure -- Shimamura Shun'ichi (島邨俊一), who lived 1862 to 1923 and was leading figure of early Japanese neurology. The novel begins near the end of his life, in 1922, but moves back and forth between earlier experiences and the last years of his life, spent in a long and withdrawn retirement surrounded by and attended to by four women: his wife, Sachiko, the daughter of his mentor; her mother, Yukiko; his own mother, Hanako; and a maidservant, Sei -- whom he: "sometimes called Anna but more often Luise" (and who he had brought with him when he retired from the Kyoto asylum he had headed, "as kind of a memento, and because no one there knew for sure whether she was a patient or one of the nurses").

It's a strange household of slow decline -- Shimamura's clothes, like everything else, slowly wearing out -- and rituals -- like a bucket of water brought to him daily, whose purpose he doesn't understand.

Shimamura's mother has been working on writing a biography of sorts of her son for years -- originally planned as a Festschrift that had since:

degenerated into a kind of bildungsroman, which in turn evolved into a family saga. And that had bogged down in a pile of lies. And suddenly what Hanako had were her own memoirs, in which her only son Shun'ichi was a marginal figure, even though he was clearly in the center of her life.She writes in secret and hides the pages, but even if much is left unspoken in the household there are few secrets:

"In our house," said Sachiko Shimamura, "everyone has gotten used to hiding things, mostly under the floor, and everyone know where the things are hidden and fingers them in secret."Shimamura, too, reads Hanako's secreted pages -- and they seem to influence his own hazy picture of the past, a fictional account that takes on a reality for him. And Sachiko suggests Hanako's endless exercise is part of a self-reïnforcing loop: "You keep rewriting his biography just because you know he keeps reading it".

Meanwhile, Sachiko -- though already thinking ahead to life after her husband has died -- plays her own little tricks to keep him off-balance, switching out a collection of toys that Shimamura keeps (obviously not very well) hidden, her reasoning being, as she explains:

"As long as he's on edge," said Sachiko, "he won't lose his will to live.Overall, however, Shimamura is less on edge than in a fog -- and that not just in his older age. Whatever clarity he seeks remains elusive.

As a medical professional, Shimamura gained quite a reputation, but he doesn't take great pride in it, "annoyed at being known solely for psychiatric wall padding and a collection of fox woodcuts". The wall padding was a useful innovation in asylums where patients could hurt themselves on hard surfaces; the woodcuts were a reminder of the pivotal events in his life. First off, there was a trip he was sent on by his mentor and future father in law in 1891, to Shimane Prefecture, to investigate women who were believed to be possessed by a fox-spirit -- presumably a variation on what was psychologically considered 'hysteria' in those times. Shimamura traveled to Shimane with a young student from a wealthy family who was to act as his assistant and photographer. It long seems a waste -- "There was no lack of foxes, but none of the patients displayed neurological symptoms [...] Most of the people had nothing wrong with them" -- and wears Shimamura down, so that his: "own condition had grown into full-blown neuro-asthenia, and his dyspepsia had become so explosive that for one whole day he thought he'd contracted cholera".

Only at the end of the trip is he pointed to: "Our celebrity. Your reward. The fox princess of Shimane", a more convincing case of fox-spirit-possession, which certainly has an effect on Shimamura. The daily log he otherwise faithfully kept remains blank for the two and half weeks spent with the patient, and at the end, as his mother puts it in her manuscript: "he returned to Tokyo a broken man", traumatized by, among other things, the disappearance of his assistant, who is assumed to have fallen to his death off a cliff.

Three years later, Shimamura gets the opportunity to go to Europe, and he meets and studies with some of the early masters of the field -- notably Jean-Martin Charcot, in Paris, and Josef Breuer (of Anna O.-case fame) in Vienna. Cultural differences prevent much meeting of minds -- with hurdles at every level, beginning with the linguistic one: Shimamura struggles to communicate in France, while even his fluent German puzzles Breuer: "His German was perfect and at the same time sounded completely Japanese". Similarly, the diagnoses and treatment of patients differs, with Shimamura amazed in Charcot's Salpêtrière-asylum by the (all female) patients:

At first glance they appeared amazingly healthy. In Tokyo, even in Matsue, the insane were much more insane. They also received more visitors.As to lessons he could take home, he found:

"The analytic conversation as a healing method for traumatic hysteria," he wrote to the imperial commission, "is of little use for Japan, as it contradicts our sense of politeness, and besides it takes too long."Shimamura remains haunted, in a variety of ways, by the fox-spirits, or the idea of them. Whether in the woodcuts he brings to Charcot or the story Breuer interprets as a form of fox-exorcism, he invariably becomes associated with them -- a burden he never entirely adequately comes to terms with (and which lingers nicely in such things like how animals are drawn to him, to the extent he can't experiment on them in the university animal laboratory: "Even in their anesthetized, poisoned, electrocuted or dissected states the lab animals still courted his favor -- they rubbed against him, nibbled at his fingers, clung to his white coat").

Living out his retirement in withdrawn isolation -- aside from the four women around him -- Shimamura does get one more shock to the system in the novel's concluding turn, a visitor from the past whom he at first can not place, but whose appearance and story fundamentally shift the underpinnings of so much of his own life.

The Fox and Dr. Shimamura is a novel about mind-games and states of mind, including their interpretations of reality -- mental health, in its broadest form, with the experts in the field when it was at its most wide-open(-to-interpretation) trying to offer different ways of understanding (it). Shimamura's is a story of shaping -- and repeatedly re-shaping -- a life story, in retrospect: much as, late in life, the good doctor is: "annoyed at being known solely for psychiatric wall padding and a collection of fox woodcuts", he can get no better grasp on his own past himself, even as he constantly struggles to come to terms with it. Typically, when he tries to relate his experiences to Breuer: "the words 'I don't remember' made frequent appearances", while the biography his mother writes (and which he stealthily read) is one that is constantly being rewritten, changing the story; typically, the most pivotal event in his life -- the two and half weeks with the patient in Shimane -- is the one period in which his notebooks remain blank.

Change and re-construction (which includes re-interpretation) are constants in the novel, like the Shinto practice of tearing down shrines and building them anew, from Sachiko's replacing small artefacts with similar ones to keep him on his toes to Hanako's book, to Shimamura's own notebooks, which he ultimately consigns to the flames. (And, of course, Wunnicke's novel is itself a reconstruction of this actual life, based on the limited sources available to her -- based partially on fact, but just as much a creation of the mind (i.e. imagination).)

The fog of uncertainty that seems to fully envelope Dr. Shimamura -- he doesn't even know (and can't even settle on) the name of the maid (or be certain whether she was a patient at one time) -- is effective, but of course also clouds the narrative as a whole; Wunnicke can never allow Shimamura the clarity that occasionally suggests itself, in Europe or with the visitor he receives towards the end of his life ("Who was that ?" he asks his wife after his guests have left, the enormity of it too much for him to handle).

It makes for an appealingly haunting novel, slightly off-kilter, suggesting the unknown and the unknowable -- and neatly contrasting a familiar period and understanding of psychology (Shimamura's European experiences) with a much less familiar Japanese world. But even as the fox-spirits may seem typically (and exotically) Japanese, they are also only another variation of the 'hysteria' that Shimamura's European counterparts were exploring at that time.

The Fox and Dr. Shimamura is an enjoyable little novel -- helped by an occasionally wicked sense of humor (Sachiko, in particular, is an inspired creation) -- but also feels like it bites off more than it can chew, the danger, in particular, of referring to and relying on well-known real life figures certainly coming to the fore here (and that's even with keeping Freud more or less at a distance ...). If not entirely a success, it nevertheless has considerable appeal. - M.A.Orthofer

http://www.complete-review.com/reviews/moddeut/wunnickec.htm

Christine Wunnicke, Missouri, Trans. by David Miller, Arsenal Pulp Press, 2010.

This earnest, violent, yet utterly transfixing gay love story is set in the nineteenth-century American Midwest. Douglas Fortescue is a successful poet who flees England for America following a scandal; Joshua Jenkins is a feral young outlaw who was taught how to shoot a man at age six. The two men meet when Joshua robs Douglas’ carriage and takes him hostage; soon, a remarkable secret is revealed, and these two very different men grow closer, even as Douglas’ brother tries to “save” him from his uncivilized surroundings

"We loved it. With surprises around each turn of the plot, this beautiful love story shows two totally opposite and very memorable characters who grow more and more alike throughout their relationship. Chosen as one of the GLBTRT Over the Rainbow Project Top Eleven for 2011, Missouri will no doubt become another classic like Brokeback Mountain." ―American Library Association GLBT Round Table

"Missouri blends Americans and Englishmen, guns and poetry, cowboys and aristocrats, creating a compelling work that's both entertaining and thought-provoking." ―Gay & Lesbian Review

"Beautifully translated.... The usual point of comparison with prose featuring cowboys is Brokeback Mountain, but Missouri is not really anything like the now infamous Annie Proulx story. Wunnicke's writing is just enough; each segment of her novel is sublimely considered and executed." ―Attitude

"Douglas Fortescue is a vaunted British poet and aesthete forced to flee to mid-1800s America with his brother after an Oscar Wildean scandal; orphaned Joshua Jenkyns is a wild-lad outlaw terrorizing the Midwest while carrying in his saddlebags Fortescue's collections of poetry - enigmatic words that speak to the boy's unarticulated sexual longings. Wunnicke's depiction of their doomed love, beautifully bleak and emotionally astute, is a most uncommon gay romance." - Richard Labonte, Book Marks

"Missouri blends Americans and Englishmen, guns and poetry, cowboys and aristocrats, creating a compelling work that's both entertaining and thought-provoking." ―Gay & Lesbian Review

"Beautifully translated.... The usual point of comparison with prose featuring cowboys is Brokeback Mountain, but Missouri is not really anything like the now infamous Annie Proulx story. Wunnicke's writing is just enough; each segment of her novel is sublimely considered and executed." ―Attitude

"Douglas Fortescue is a vaunted British poet and aesthete forced to flee to mid-1800s America with his brother after an Oscar Wildean scandal; orphaned Joshua Jenkyns is a wild-lad outlaw terrorizing the Midwest while carrying in his saddlebags Fortescue's collections of poetry - enigmatic words that speak to the boy's unarticulated sexual longings. Wunnicke's depiction of their doomed love, beautifully bleak and emotionally astute, is a most uncommon gay romance." - Richard Labonte, Book Marks

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.