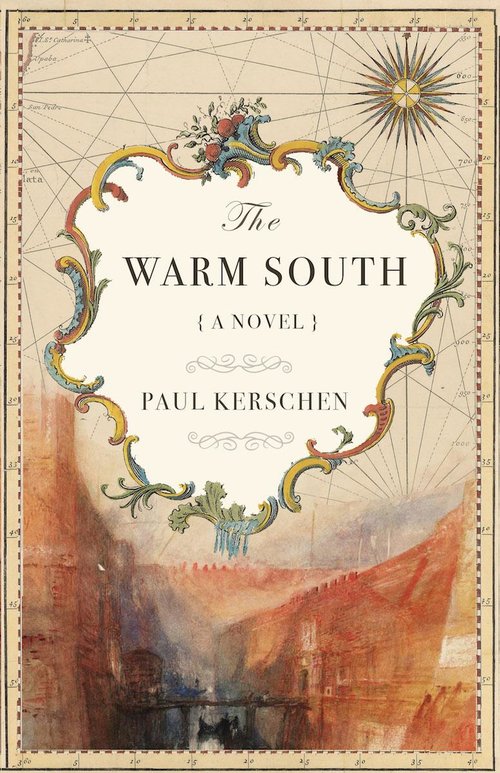

Paul Kerschen, The Warm South: A novel, Roundabout Press, 2019.

https://warmsouth.com/

http://www.paulkerschen.com/

read it at Google Books

The daringly imagined, masterfully realized story of poet John Keats's second life abroad.

What if Keats had not died in Rome at only twenty-five, just as he was coming to realize his poetic gifts? In this audacious alternate telling, the young poet is pulled back from the brink of death only to find his troubles far from over. He is short on money, far from home, his literary reputation anything but assured—but his life and imagination have been spared, and a new country awaits.

In an Italy at uneasy peace, full of foreign armies and spies, Keats is drawn into Percy and Mary Shelley's expatriate circle, resumes his old profession of surgery and falls in with student revolutionaries who are plotting a more radical cure for their nation. His fiancée in London expects his return, and everyone is expecting his next poem, but he has not returned from his deathbed quite the same person—or poet—that he was.

Written with deep knowledge, compassion and brio, Paul Kerschen's debut novel is a spellbinding historical yarn and a heady engagement with the literature of the past, a thing of beauty in itself and a meditation on the writer's duty in troubled times.

“An ambitious, thrilling work of the imagination… The Warm South is so much: a love story, a historical thriller, a great literary what-if, and a profound meditation on the act of creation itself.” - DANIEL MASON

“A lyrical and profound exploration of mortality, second chances, art, and ambition. Kerschen writes an alternate history for the beloved poet Keats, allowing him to rise from an early deathbed and experience the gory operating theaters of Pisa, the decadence of Italian Carnival, and a seductive and sometimes dangerous entanglement with Mary and Percy Shelley. Written with elegance and heart, The Warm South pulses with life. - FRANCES DE PONTES PEEBLES

“Paul Kerschen’s miraculous first novel grants the poet John Keats an extended life in Italy as the surgeon he trained to be, and as the husband and father he never became. Superbly imagined, impeccably written, uncanny in its intimacy with Keats’s mind and feelings, this book also conjures the Italy in which Keats lived and died—and here lives on. Kerschen brings this mate- rial astonishingly alive and close. This is the best novel I’ve read all year.” - CARTER SCHOLZ

“The Warm South offers an alternate biography, a second chance—a daring and deeply imagined portrait of genius made more human, more accessible, and more moving and vital than any history or scholarship can allow.” - VU TRAN

“A bold strike. Kerschen applies SF’s classic ‘what if’ to literature itself. And like stern Mary Shelley’s monster, the dead poet stirs, and rises, and walks. But the path between the old world and his new friends is steep… Come.” - TERRY BISSON

The Warm South begins where a dozen biographies end and a hundred poems linger, in 1821 at the Roman deathbed of twenty-five-year-old John Keats, the definitive dead poet, an orphaned unrecognized genius cruelly cut down through no fault of his own. The fellow who said, “Beauty is truth; truth beauty.”

Not a promising subject for fiction, then, outside of dewy-eyed bio-pics and other vehicles in need of a tragic young death. Whereas by page four of The Warm South, we find a “John Keats” whose fatal tuberculosis is in complete remission, miraculously so far we’re concerned, but well within the bizarre range of prognoses imagined by his doctor.

To that extent, Paul Kerschen has written an alternate history. Thereafter, however, he adheres to the regulations of well-researched historical fiction, and history rewards his attention. Fellow tragic Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and novelist Mary Shelley conveniently resided in Italy at that time, and had already invited Keats to visit them. The Shelleys’ physician in Pisa, and their closest Italian friend, Andrea Vaccà Berlinghieri, was a free-thinker who, like Keats, had studied medicine in London. Tragic Romantic rock star Lord Byron and Greek revolutionary leader Alexandros Mavrokordatos were on the scene as well. A novelist could hardly request a more fully stocked scene.

History is less kind to the novelist’s characters. If nothing else, death is a reliable solver of problems; resurrection restores them with interest. Then as now the first gift received by the convalescent will likely be an unpayable medical bill:

“Forgive me, Joe,” he said. “It is the melancholy. It came first of my illnesses, and it will be the last to take leave.”“So says Doctor Clark. The nervous fibers.”“I do not speak of fibers,” said Keats. “It is the trouble I have put you to. I’ve so depended on you, and on everyone, I don’t know how I am to make good.”“It is nothing,” said Severn.“I shall settle my debts to the penny.”He had said it to give confidence. But Severn turned aside with a twist to his mouth, and Keats realized he was embarrassed to have such a promise made him by a sickly man in a nightshirt, sitting up in the cot that ought to have been his deathbed.

Elevated diction aside, Kerschen’s prose-about-poets is appropriately mellifluous, alert, and hungry throughout, even if lengthy effusions in re Tuscan landscapes are lacking—and again appropriately, since Keats, despite his nominal tributes to “A Nightingale” and “Autumn,” remained to the last a city boy fed by human company and bookish culture.

Which returns us to the matter of diction. To a contemporary American ear, raised on our impoverished grammar, multitudinous contractions, and liberal strewing of obscenities, the dialogue of educated Georgian English characters sounds painstakingly cautious, as if the speakers were picking their way towards the nearest exit across a room of unpredictably hostile or clingy vipers. And that is, more or less, how this generation of English poets dealt with the impossibly conflicting demands of maturity.

As of 1821, on retreat from the most scandalous divorce of his era, Byron had blossomed into a bloated bullying prototype of Christopher Hitchens. After the deaths of three children, Mary Shelley radiated unrelenting anger and depression; her husband sought shelter in a series of absurdly idealized infatuations. Lacking Shelley’s and Byron’s upper-class assurance or income, Keats spent the entirety of his documented life thrashing between warm declarations of affection and distrustful retreats into solitude. All three men followed the same basic strategy: desperate escapes from unbearable claustrophobia into freshly problematic circumstances, carrying a heavier load of unmet obligations each time.

Kerschen’s revived Keats maintains his accustomed erratic path: deserting his Roman support group, dropping his correspondence with English lover and friends, recoiling from literature to medicine.... After an attempt to untangle the Shelley ménage ends in ambiguous signals from both spouses—

His golden lashes blinked. He tilted his head, furrowed his brow in strange inquiry and, moving very close, pressed his lips lightly and chastely against Keats’s closed mouth. For a heartbeat he hung silent, as if waiting on a question, then spun about and went at a soft tread up the steps.

—Keats characteristically reflects:

All that had happened at the Shelleys’ was a dream of warning. He dare not take a wife.

And then elopes with the sixteen-year-old daughter of his benefactor.

The Italian characters, naturally, feel more at home than the English, albeit not a home they can claim as their own. Occupied by Austrian soldiers, Tuscany, like the rest of post-Napoleonic Europe, is controlled by regressive regimes dedicated to furthering the gulf between rich and poor, prone to treat science as conspiratorial sedition, and happy to meet dissent with imprisonment, exile, or execution.

Such dark times demand political action alongside all maturity’s other impossibly conflicting demands; indeed, it’s difficult to conceive any action which is not political in some sense. The Italians protest, take up arms, are jailed, are shot. Byron and Shelley write regicidal satires and dream of resurgent liberating armies. Keats’s attempts at activism are more obscure, if just as ultimately ineffective: self-sacrifice (and teenage-bride-sacrifice) at a one-man Doctors Without Borders outpost in malarial marshland, followed by the production of a poetic tragedy on “The Death of Danton,” which triggers a riot without even benefit of a summons to liberty.

A girl’s thighs are thy guillotine. The mountOf Venus shall be thy Tarpeian rock.

At Carnival, Percy Bysshe Shelley and the young Pisan patriots masquerade as carbonari; Keats dresses as Mary Shelley:

Keats turned, legs moving free in the skirts, and pressed himself to the wall. Giuditta considered him. “I would do more, with more time,” she said. “Your hair should be dressed. And I would powder you here.” She waved where his breastbone came up pale and knobbed from the bustline, like something that had grown on a tree. Then she looked up and laughed.“Now don’t look sad!” she said. “You’re a fine girl.”“Ciabatte!” called someone. A pair of ribboned shoes was passed over the curtain and Keats held his foot out; but they were minuscule, made for a child, and Giuditta put them aside.“You’ll do well enough in your stockings,” she said. “Are you ready?”

On Keats’s marriage, a bit more than halfway through the book, our gaze is averted. The narrative torch passes, to Chorus of Peasants, to outsiders like the Wodehousian Joe Severn and Keats’s unknowingly discarded English rose, Fanny Brawne, who sustains the antic humor which Keats has stifled beneath the burden of Universal Justice. The troupe assembles; the missing are called in; the range of possibility widens and occasionally lightens, even while braided catastrophes (a ruined dinner, an awful party, to prison, to death-by-water) pop like well-ordered fireworks: these might be the precipitants of a Big Heist, or an operatic finale, or the resolution of a Lubitsch sex farce.

And as implicitly promised we are in the end rewarded. Truth and beauty, obligation and independence, drop into conjunction for a day, or a few hours. Long enough to remember at least.

Is our reward deserved? In such dark times—the early nineteenth century; the early twenty-first—can such trivial pleasures even be justified?

Certainly not, but The Warm South graciously reminded me that rewards, just as surely as punishments, may be both undeserved and undeniable. - Ray Davis

http://www.musicandliterature.org/reviews/2019/5/11/paul-kerschens-the-warm-south

In The Warm South, novelist Paul Kerschen performs a resurrection. The body is that of John Keats, dead at age twenty-five of tuberculosis. Dying in 1821, Keats had written his greatest poetry in the concentrated three-year period immediately preceding. He died on a medically-prescribed trip to Rome with his friend, painter Joseph Severn, leaving behind an outstanding invitation to visit Pisa from Percy Bysshe and Mary Shelley and an outstanding engagement to his London fiancée, Fanny Brawne.

The Warm South restores Keats from his deadly illness and threads his loose ends into a narrative around all of Keats’s selves: the writer, the aesthete, the friend, the lover, and the surgeon. Keats returns to the medical work that he had abandoned. He grows close with the Shelleys and clashes with Lord Byron. He gets involved, tentatively, in the tumultuous politics of 1820s Italy. He agonizes over his tortuous engagement. And he does write again, though what he writes is one of the great surprises of the novel.

The Warm South may seem an unfashionable book in that it does not proclaim its immediate political or sociological relevance. Yet Europe’s political tumult in the 1820s, in Kerschen’s portrayal, comes to resemble our own, with an old elite increasingly dislodged but no clear progressive force ascendant. And Keats, a dislocated (in several ways) soul who possessed the same “negative capability” which he ascribed to Shakespeare, stands partly withdrawn from the events around him, struggling to find a place in which he and his work can contribute. Keats’s answer to that problem in The Warm South is circuitous, pained, and not without strife, but ultimately affirmative.

I spoke to Paul Kerschen regarding the inspiration for his novel and how he shaped the resurrected Keats.

David Auerbach: You clearly took joy in writing your version of Keats. Is The Warm South fan fiction of a sort?

Paul Kerschen: No doubt! There must also be a touch of Frankenstein in my resurrecting him for my own purposes. I gained and lost a great deal over the course of writing, but whatever the endpoint, it did at least start from a felt intimacy with Keats’s own words, and perhaps in that respect it isn’t too much worse a distortion than other kinds of reading.

Why Keats?

For me at least, Keats is one of those writers where the felt affinity is so personal and idiosyncratic that you're always surprised to find it so broadly shared. His poetry is almost wholly guileless, and that lack of guile makes him very vulnerable—he’s always risking failure of the most open and embarrassing kind. We have the odes, of course, and the other perfect short pieces that show up in anthologies, but next to those are so many failed experiments and false starts—in part because of his early death, but also because his gifts were often in a different key from the themes he tried to take up. In that sense he’s the total opposite of a poet like Yeats, where the technical and rhetorical command is so broad and complete that however you respond to him personally, you never question why he’s in the canon.

I first thought of attempting a novel about Keats a long time ago, on my first reading of “Hyperion.” That poem is one of his astonishing failures; if he’d somehow managed to complete it, we’d think of it as a worthy footnote to Milton, but his temperament was fatal to the project in a much more interesting way. It’s staged as an allegorical revolution, like Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound, in which a new order is supposed to overthrow the old tyrants, but Keats never gets to the actual point of conflict because he’s too caught up in the suffering of the fallen Titans. Their pains are superhuman, described as lavishly as his other poems describe sensory pleasure, and are obviously informed by his knowledge of medical science. I’d never read anything like it. It’s easy to point out where the poem is derivative of Paradise Lost, but that hushed communion with suffering is a quality all its own, and it completely enraptured me, all the more because it was tied to failure. It seemed so modern; in my private mental library it might sit next to Kafka, another fragmentary writer whose presence in the canon can still surprise when it so often seems he’s speaking to you alone. Before I knew anything else about my own book, I knew I wanted to follow that thread.

For readers with only casual familiarity with Keats and the Romantic era, what is important to know about them in grappling with your novel?

I hope that a casual familiarity will get them pretty far! At any rate, I didn’t want specialized knowledge to be an admissions requirement, and one of the pleasant challenges of writing historical fiction is to have the book disclose its own world without its intermediary stance becoming too obvious. Of course there are some things the book isn’t allowed to telegraph, most obviously its own counterfactuality; it might head off some confusion to be clear that it picks up in February 1821, at the point where, according to the biographies and Wikipedia, Keats has expired. Likewise worth a note might be the politics of the time, which seemed very much as desperate as our own. Napoleon’s defeat had installed reactionary absolute monarchies across the continent, with an Austrian police state to back them up, and in Britain the same conservative ministers who had overseen George III’s dotage were now confronting nationwide protests from a working class displaced by industrialization and suffering postwar famine, culminating in the infamous armed massacre at Peterloo. The later part of the century would bring about Italian unification and the British reform bills, but in 1821, the path seemed long indeed.

How did you conceive of Keats’s (rather eventful) further adventures?

To start with, I had biography to hang my hat on. Shelley really had hoped for Keats to join him in Pisa, and Keats really had exhausted his own and his friends’ money in getting to Italy and had nothing to draw on in the event of a recovery. When I thought of him abroad, I thought of his letters from an 1818 walking tour of Scotland and Ireland. These show him to be an eager and curious traveler, always alive to the people around him; even a rather awful description from the Irish countryside of “a squalid old woman squat like an ape half starved” concludes with the thought, “What a thing would be the history of her life and sensations.” That passage may not be the most enlightened, but there’s still a curiosity there, in which he seems to go beyond his time. When you read period travelogues from the Mediterranean, the British are always admiring the picturesque past and repelled by the inhabitants at present. A traveler like Byron might get caught up in the romance of a popular revolt, but generally the Italian population is seen as the degraded remnant of a once-great race. I hoped that Keats might see more and do more, that he might enter the life of Italy as others wouldn’t—and of course, without money at his disposal, the plot could more easily compel him to do so.

The other presiding puzzle to work out was Keats’s relationship with Fanny Brawne. This is the most agonizingly incomplete part of the present-day legend of Keats; his literary achievement is secure for us, but the thwarted love story is pure tragedy. The pull of having Keats immediately return to England and marry Fanny had to be resisted, since that would make for a very short book. As a counterweight I use Keats’s own ambivalence about women and marriage, which shows up in so many of his letters (including the passage you quote below) and threads the fear of constraint through every profession of desire. This fear shows the most glaring gap in his otherwise broad sympathies; I do think it was a quality of youth that he might have outgrown with a more settled position in life, and the novel does its best to test that hypothesis. To that end, there needed to be several prominent women in the book, with well-defined stories of their own. There’s Mary Shelley, as you bring up below, but also a purely fictional adolescent Italian girl, and later in the book, Fanny Brawne herself takes on a more active role. I’m not sure the book’s structure allows it to pass the Bechdel test even so, but it was intended to be in that spirit. - David Auerbach

read more here: A Conversation with Paul Kerschen

Paul Kerschen, The Drowned Library, Foxhead Books, 2011.

excerpt (issuu)

0.0.0.5. Romulus.

0.0.0.7. Tlaloc.

0.0.0.8. Xronos.

Paul Kerschen's virtuosic debut dives into mythologies from around the world and brings back strange treasure. By turns lyrical, funny, enigmatic and harrowing, these nine stories leap with audacity and grace across styles and settings, from ancient Greece and Palestine to the border towns and office parks of today. A soldier returned from Iraq is haunted by the vision of a giant holding the world on his shoulders. A dying writer creates a secret dictionary and receives a divine visit. A migrant worker in the Southwest confronts the deadly emptiness of the desert. The labors of Hercules, the resurrection of Lazarus and the founding of Rome are given startling new tellings. THE DROWNED LIBRARY is in a class all its own, and introduces a remarkable new writer.

On November 1, a month before the announced release date, and because they were too excited to wait, Foxhead Books released The Drowned Library, Paul Kerschen’s (Ph.D. ’10) first collection of short stories. Even before reading it, I was already a big Paul Kerschen fan. I knew him as a Joyce scholar, a talented musician and composer, and as the person whom the English department frequently called upon to answer internet-related questions, since Paul is also a computer programmer extraordinaire. The Drowned Library only gave me more reasons to keep cheering.

For each of the stunning nine short stories, The Drowned Library thematizes a different mythological figure. Paul says he wrote The Drowned Library as “an alternative to the contemporary American style, which is so autobiographical, so concerned with expressing your own experience.” He wanted to take a page from early modern writerly practices, and use well-known stories as the occasion for experiments with form.

I had the distinct pleasure recently of talking with Paul about The Drowned Library, and about writing in general, which he calls, “the least oppressive labor I have ever performed.”

MH: What book made you want to be a literary scholar? Is it different from the book that made you want to be a writer?- berkeleyenglishblog.wordpress.com/2012/01/17/foxhead-books-releases-_the-drowned-library_/

PK: Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist made me want to be a writer, and being a literary scholar branched out from that. My senior year in high school we were given Portrait of the Artist. Everyone else hated Stephen. I didn’t discover you weren’t supposed to like him until later. There were levels of understanding I had to go through, but it was that particular book, and the pure linguistic inventiveness of it …

MH: In an interview with Foxhead Books, you mention that when you first began the project, you thought you were going to be writing parables. What attracted you to the parable?

PK: … The parable tends to be short. [MH chuckles] That was certainly an attraction: the compactness of it, [and] concision and compression as a virtue. I came to this project after writing a couple longer novel-length projects. I was thinking a lot about Kafka, and very, very short paragraphs that make up a short story, which state three things and imply about ninety depending on how you want to interpret it. I thought writing parables would be a useful kind of discipline to keep me from running off on too many conflicting avenues.

MH: In the same interview you say the book “ends up tracking the experimental process.” Which experiment most surprised you?

PK: I suppose they generally tended to surprise me more as you get into the book. The story “Tlaloc” … [which] starts out raising a sort of question about the protagonist, then turns into a nested story. [It] never comes around back to the beginning and just sort of stops and hangs. It ends up hanging in a way that fulfills a principle of composition.

The other one that kept surprising me was “Thoth.” It starts out with one particular conceit of very short paragraphs done as dictionary entries, [but it] needed some other element to bring the story to the close. By the end, the form itself had to change. That was certainly not something that I had planned from the start.

One thing about writing [is that] it’s like a performance, but it’s a performance for which you have infinite rehearsal time. For someone like me, I often feel awkward or inarticulate in spontaneous conversation. Being able to have the luxury of time to make sure I’m not screwing it up is sort of an attractive thing to me.

MH: In our conversation with distinguished alumn Jeff Berg (’69) he said his conception of creativity hasn’t changed much as Chairman and CEO of ICM from when he was an undergraduate at Cal. Has yours changed?

PK: For me it’s very much been a process of getting less and less naive over time. With Portrait you start thinking Stephen is who Stephen believes himself to be. I came to Berkeley having done an MFA at Iowa Writer’s Workshop, where there are certain sorts of questions about the underlying assumptions of literature and creativity that don’t get asked. It’s very different from a Ph. D. environment [where] it’s all “hermeneutics of suspicion.” Iowa wasn’t. The sort of romantic writerly myth is in vogue there: the idea that to be a writer you go out and you experience life, and you suffer and you work to the true expression of your self. All these ideas I now understand as Romanticism, as filtered through modernism, as filtered through a romantic myth of Hemingway.

Writing isn’t only the expression of self. It’s a dialectic between self and history, or between a literary past and the social world surrounding the writer.

So the short answer is that coming out of an MFA program, you tend you think of writing as the pure unmediated expression of self. I now understand it as a much more interesting process of work within preexisting structures of language and history in order to do something that’s the latest link in the chain. That’s one reason why turning back to myth is more interesting to me, as an alternative to the contemporary American style, which is so autobiographical, so concerned with expressing your own experience; I wanted to get away from that. These are very old stories and very often-told stories.

MH: Why did you fixate on these particular figures?

PK: These figures happened to best encapsulate things I had been thinking about. Thoth is obvious enough: a god of writing. [MH: “That was my favorite one!”] There’s an edition of Derrida’s On Grammatology that has Thoth on the cover. With him, I was thinking about the materiality of language, the nature of language. Of course what’s interesting about Thoth is that in the ancient Egyptian cycles, Thoth doesn’t go on quests, he doesn’t sit in judgments. He’s just there, a god of writing that’s just there. That he exists outside time was an interesting way to describe language, a medium that’s always already there and you can’t get behind it.

In “Tlaloc”, the figure itself doesn’t play into the story, but is useful as a picture of the environment of the desert, where it takes place. I grew up in Tucson, and … after I got my MFA, I tried to move back to the desert, but I loved the environment of the city and the politics that find expression there, so I ended up going to school in Berkeley. I knew I wanted to write something about [the desert], so there was the figure of the Aztec god.

The story called “Philomela” is almost a literal translation of Ovid. With that one, I was thinking a lot of Beckett or Gertrude Stein, who worked with very short sentences and tried to reduce language to some kind of simple objecthood. Especially Beckett, who is so distrustful of language, and wants to pin words down, seemed perfect for Philomela who loses the ability to speak. [In the story] you go from the linguistic or narrative human to non-linguistic realm of humans to a non-linguistic eternal nature where everyone becomes birds, to play with the boundaries of language, to get around language.

MH: In different ways, Atlas, Eleazar, Eurystheus, Ragnarok, Thoth take up the question, “what is work?” or “what is worthwhile” or what does work do?

PK: [In graduate school] I didn’t get as deep into Marx and that realm of thinking [as others did, but] it certainly had some influence on me, and as I moved way from my MFA idea of art as the act of a solitary artist to a more complex view of language and narrative as happening within social forces, the fact of work and the necessity of work, and people always having to work for goals that are the most immediate ones, to the extent that the stories describe some kind of social reality, there was no way around it.

With “Ragnarok”, I wrote that one during a summer job, in which I was working in an office working with personality conflicts, and [I had] to deal with [them] instead of staying home with my books, which is all I wanted to do…

For “Eurystheus”, it might be the point where Hercules has to go deal with horse shit. That task is put on him as a task of humility …. If you go out and slay monsters, it’s still a warrior thing …. Even in the sources, it’s clear that this is put on him as a kind of humiliation …. He finds a way to direct the river to clean out the stable and not have to go into it. With Eurystheus as the speaker in the story, it was interesting to be able to throw out the suggestion that Hercules missed the entire point of the task, that perhaps there is something morally questionable in lacking or not being able to humble yourself to this task …. It brings up the possibility of the dignity of work even if people aren’t often given the chance to experience it. It would be a false picture of creativity that it exists totally outside the economic sphere, or that it’s not a labor in and of itself. It is the least oppressive labor I have performed….

- 0.1.0. The Modernist Novel Speaks Its Mind (Ph.D. dissertation, 2010).

- 0.1.1. Mercè Rodoreda and the Style of Innocence (Quarterly Conversation, 2012).

- 0.1.2. Krasznahorkai’s Pilgrimages (Music & Literature, 2013).

- 0.1.3. Sour, Salty, Bitter, Spicy, Sweet: On Five Spice Street (Music & Literature, 2014).

- 0.1.4. Mercè Rodoreda, War, So Much War (TLS, 2016).

- 0.1.5. Javier Cercas, The Impostor (TLS, 2018).

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.