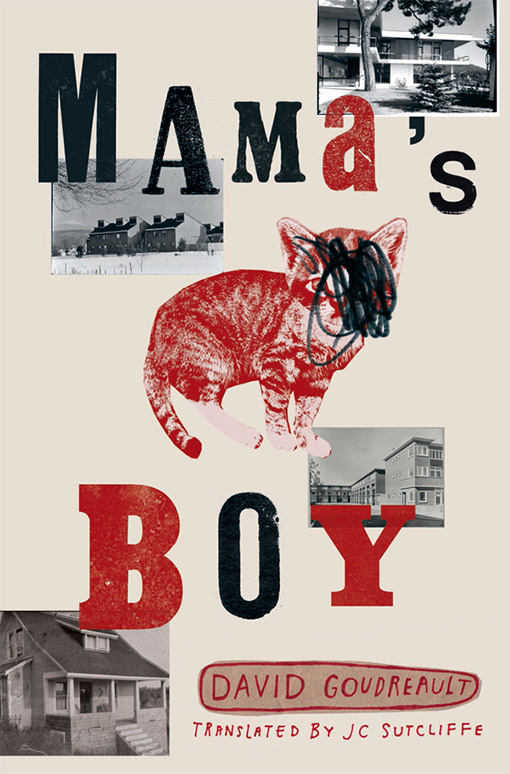

David Goudreault, Mamma’s Boy, Trans. by JC Sutcliffe, Book*hug, 2018.

Read an Excerpt: Open Book

Winner of the 2016 Grand Prix littéraire Archambault

My mother was always committing suicide. She started out young, in an amateur capacity. But it didn’t take long for Mama to work out how to make psychiatrists take notice, and to get the respect reserved for the most serious cases.

Written with gritty humour in the form of a confession, Mama’s Boy recounts the family drama of a young man who sets out in search of his mother after a childhood spent shuffling from one foster home to another. A bizarre character with a skewed view of the world, he leads the reader on a quest that is both tender and violent.

A runaway bestseller among French readers, Mama’s Boy is the first book in a trilogy that took Quebec by storm, winning the 2016 Grand Prix littéraire Archambault, and selling more than twenty thousand copies. Now, thanks to translator JC Sutcliffe, English readers will have the opportunity to absorb this darkly funny and disturbing novel from one of Quebec’s shining literary stars.

“David Goudreault will captivate you from the first line!” —Kim Thuy, author of Vi and Ru

“This is a ‘tour de force’ by David Goudreault, a powerful first novel, written in a chiseled, paced, visual style that one is not ready to forget.” —Huffington Post

“A fierce, pugnacious, and dazzling tale, the trailer of which could be set to a Pixies song (remember Fight Club?).” —Le Vif/L’Express (Belgique)

“David Goudreault stays his course, explaining nothing, forcing the reader to make up his own mind about this character, lost and endearing in spite of his madness, his self-absorption, and his cruelty.” —Culturebox (France

"David Goudreault will captivate you from the first line!"--Kim Thuy

Goudreault’s darkly humorous but disturbing debut, originally published in 2015 and now translated by PW reviewer Sutcliffe, takes readers into the life and mind of a young Quebecois man and charts his descent from a traumatic childhood into a life of crime. The unnamed narrator’s story begins when he is seven and observes that his “mother was always committing suicide. She started out young, in a purely amateur capacity. But it wasn’t long before Mama figured out how to make the psychiatrists take notice.” After recalling the first time he found her after one of her attempts and ran for help, he relates being taken away from his mother, shunted through many foster homes and institutions, and left to grow up entirely friendless and lacking empathy. “Friendship implies a certain amount of giving of oneself,” he muses, “and I haven’t even got enough of me for myself.” His adult life is driven by his needs for alcohol, drugs, and sex and a quest to find his mother, all of which require theft, lying, and taking advantage of anyone who gets close to him. Despite the narrator’s repellent behavior, readers will be drawn in by his quick wit, sharp observations, and childlike longing for his mother’s love. - Publishers Weekly

This incredibly fun novel is a first-person account and confession by the unnamed protagonist, who offers his side of the story to what he claims is the jury for his own trial. In the opening page he lets the reader know:

“In my memory, in my mind, this is what happened. It’s my truth and that’s the only one that counts . . . I’ll let you be the judge. I’ll judge you too, in due course.”What drives this book is the shocking, twisted, and ultimately hilarious worldview of its narrator. The story revolves around the protagonist’s quest to find his suicidal mother, from whom he was taken at a young age by Social Services. He intends to reunite with her, and genuinely believes that this reunification will be life-altering and will somehow drastically improve his life. Hopping from foster home to foster home, the narrator develops a misplaced sense of empathy, a partial misunderstanding of social cues, and a firm belief in his own righteousness. He is terrifying, a delinquent, a stalker, constantly on amphetamines and on the verge of a violent breakout that keeps the reader on edge. At the start of the novel he logs into the email account of his girlfriend (of just three weeks) after she starts to become distant, only to grow jealous of old love messages she’d written to an ex. He then decides to kidnap one of her cats and write her a letter:

“As a postscript, I explained that I was taking her cats because she cared about them more than she cared about me, until she decided to put more effort in and not contact Gregory anymore.”I won’t say what happens next, but it does not end well for the cat. Mixing with moments of sweetness, uncompromising shock, violence, and humor, the reader’s own (hopefully) more healthy perception of reality becomes a character in and of itself, both enjoying and struggling with Goudreault’s protagonist.

The boldest aspect of Mamma’s Boy is the deep understanding of psychological normality and its absolute violation in the character construction of its protagonist, without ever falling into the realm of psychosis, the delusions of the protagonist allow him believe things for which he has no evidence. Unreliable as the narrator may be, awful and violent, his journey is one that absolutely captivates you and makes you want to turn the page. The pain of a young maladapted adult and the evidence of how social systems fail to notice or appropriately assist those that may need it most are issues indirectly central to the story. He believes himself to be extremely intelligent and handsome, handing out advice such as “You don’t show up to visit someone empty-handed. You need flowers or a weapon, it’s well documented,” and doing things such as “I drank too much, smoked too much, fucked Nicole again. I didn’t even want to, but when it’s there for the taking . . .”

Mamma’s Boy is dark and twisted, but it is also incredibly amusing and raw. David Goudreault is a Quebecer writer who won the first World Cup of Slam Poetry and has received awards such as the Grand Prix littéraire Archambault for this very novel. - Rafael Sanchez Montes

http://www.rochester.edu/College/translation/threepercent/2018/10/25/mammas-boy-by-david-goudreault/

This is the second of two books from the Quebec based publisher Book*hug . This was David Goudreault debut novel he has written novel and poetry and is also a songwriter he was the first Quebecer to win the Poetry slam world cup. he has written four novels and this is his first to appear in English. He leads creative workshops in schools and detention centers all across Quebec. He has won a number prizes this won the Grand prix literaire Archambault.

My mother was always committing suicide. She started out young, in a purely amateur capacity.But it wasn’t long before mama figured out how to make the psychiatrists take notice, and tp get the respect only the most serios cases warranted. ELectroshocks, massive doses of antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics and other mood stabilizers marked the seasons as she struggled through them. While I collected hockey cards, she collected diagnoses.Thanks to the huge effort she put into her crises, my mother contributed greatly to the advancement of psychaitry. If It weren’t for the little matter of patient confidentiality, I’m sure several hospitals would be named after her.This is one man’s journey to find his mother after he was placed in care and spent his teen years in a series of various foster homes have made this man the character he is today and now he is trying to find his mother. As her mental health problems sent him into care. The book opens with an indication of how bad his mother was when he says she was always trying to commit suicide. He uses various names as the book unfolds during the story and shows the good and bad sides of foster care each family he has a nickname for them usually about the way the family is with him or they act. He isn’t the most well-adjusted person a man of his upbringing and surroundings. At one point we see him kidnap his girlfriends cat in a jealous rage they had only been together a few short weeks. HIs turning out of the care system and taking drugs and getting tattoos and his first steps into becoming a man. The narrator has a dark side that we as a reader should really hate but at times, we can find him charismatic. He finds a job using lies to get near to where his mother lives to try to find that right moment to return to her life. As he waits and recounts the mother he remembered and the woman now.

The first paragraph opens your eyes to the relationship with his mother growing up.

I celebrated my eighteenth birthday by spending half of my first welfare cheque on a tatoo. For humans- unlike cattle- marking your body is a sign of liberty. I’d learned this during my hours online. I needed something original, something unique that really represented me. I got a tatoo of a big Chinese character on the back of my neck. Strength.That;s what the tatoo meant. It was impressiveThis is one of those books that as a reader whether you like it or hate it will hinge on how much you like the narrator of the book. I put him between Holden Caulfield and Patrick Bateman on the scale of how much you could dislike this character he has a skewed view of the world as we would see it here in the UK he is prime for being on the Jeremy Kyle show. A rollercoaster ride an insight into how being in care effects you as a person it shows how he hasn’t formed normal social interaction and the views he shows also show a lack of proper role models in his life . A powerful voice if hard to read at times once again another outstanding read from Quebec. The book could easily be transferred to here in the UK the experiences and the life he has had could be the same of man a young man in the UK that has gone through the struggling social care system. - winstonsdad.wordpress.com/2019/03/08/mamas-boy-by-david-goudreault/

He spends his first real money very unwisely on a tatoo but it is also a sign of his struggling and what he needs to move forward

David Goudreault’s Mama’s Boy (translated by JC Sutcliffe, review copy courtesy of Book*hug) is a first-person account of the life of a young man growing up in Quebec. His childhood is punctuated by a series of moves, mostly caused by his mother’s suicide attempts, and after the pair are finally parted when he’s seven years old, he’s sent to a number of foster homes, none of which work out. Despite falling into bad habits, our friend is an optimistic soul, believing that things will somehow work out for the best.

Proof of this comes when he is tipped off years later as to the whereabouts of his mother, whom he had assumed to have finally managed to kill herself long ago. With a new purpose to his life, he moves to a new town, gets a new job and carefully checks out his mother’s new life in preparation for a tearful reunion. The thing is, it’s been a long time since the pair were separated, and the reader senses that he may not get the warm welcome he’s been waiting for…

That’s one way of looking at Mama’s Boy, but this brief summary leaves out one tiny, but essential, detail – the narrator happens to be a psychopath. Right from his early days, he happily recounts events you’d rather not hear about:

For several months, I’d been in the habit of torturing animals whenever I was frustrated. I must have been very frustrated on that particular day. The animal didn’t survive the combination of centrifugal force and my bedroom door frame. It made an odd noise, soft and dry at the same time.

p.22 (Book*hug, 2018)

This is just the first of a litany of horrible actions, and with this knowledge, you can probably read between the lines of the summary above. For ‘move to a new town’, read ‘shoot through with his landlady’s money’ and for ‘checks out his mother’s new life’ read ‘stalks her relentlessly’ 😦

I have to admit that I struggled a little with Goudreault’s novel in the early stages. With the story told in the narrator’s matter-of-fact voice, relating one vile action after another, you really wonder what’s in it for you, the reader. The casual sexism and homophobia are bad enough, but when he moves on to actually committing crimes, it’s tempting to call it a day, particularly when you sense that this can only spiral into ever greater acts of violence.

Luckily, though, Mama’s Boy does contain a bit of a twist, and that has much to do with the way the story is told completely through the eyes of our deranged narrator. You see, while he talks the talk, he doesn’t always walk the walk, and eventually we realise that our friend is very much a Loser (with the capital L firmly emphasised). It’s here that the humour starts to outweigh the darkness, with Goudreault letting us in on the joke, allowing his anti-hero just enough rope to hang himself (if never fatally):

The idea of settling down to a stable job at the SPCA crossed my mind the same way you cross the street – fairly quickly. I remembered where I’d come from, my principles and my values. I didn’t want to be anyone’s peon just to enrich the system. I don’t believe in work, it’s a form of modern slavery. I’ve read Richard Marx. He’s an author who’s really down on capitalism. (p.74)

Das Kapital and Hazard – a talented man 😉

It’s no coincidence that I began to enjoy the book more once the narrator set off to look for his mother, at the same time attempting to fit into real life in his own deluded way. He’s surprisingly suited to the job he finds at the SPCA (the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals) given that his tasks include putting down unwanted pets and shooting unruly dogs with tranquiliser darts, and he makes a connection between the abandoned pets and his own life:

It’s actually the same problem with foster families. People are keen to take their cheque and shine their halo, but they don’t want the problem kids, the disabled ones, or any other demanding little brats. People want children in need, but just enough to fill their own needs. Abandoned animals and children are advised to be cute. I’m well placed to tell you this. (p.68)

Despite his misgivings, his work occasionally gives him a sense of achievement, and you could almost imagine him actually turning over a new leaf and settling down…

…for about five minutes, anyway. Once he gets out of his uniform, it’s back to staking out his mother’s house, taking enough drugs to floor an elephant and hooking up with women he met online. The longer the story goes, the more we see just how distorted his view of himself is. The image of a good-looking hard-fighting man, popular with the ladies and impressive in bed, is chipped away at, scene by scene, only kept from melting away entirely by our friend’s seemingly bomb-proof self-confidence. No matter how bad the situation, how brutal the beating, there’s always a sense that this was all just down to bad luck, and that tomorrow will see things turn his way.

Mama’s Boy won’t be for everyone (and if you’re a cat lover, this comes with a ten-mile-high neon trigger warning…), but the gradual development of the main character, or at least our perception of him, makes this an interesting read. And if you enjoy it, I have good news for you. The author bio at the back of the book says there are a couple of sequels, both of which will be brought out by Book*hug in due course. Obviously, this is one man it’s hard to keep down, even with the police, strippers and the Canadian SPCA on his trail. Oh, and his mum, of course. - Tony Malone

https://tonysreadinglist.wordpress.com/2019/03/07/mamas-boy-by-david-goudreault-review/

Why you need to read this now:

Mama’s Boy, our anti-hero, is a particularly unpleasant character for these misogynistic times. He’s completely self-absorbed, socially inappropriate at best, cruel at worst. Overwhelmed with pain he tries to hide, and love he has nowhere to channel, this lonely young man is wrong about just about everything, but convinced he’s the only one who can see clearly.

This novel, the first in a trilogy, tells the story of the narrator growing up alone, having been separated from his mother as a young child. He moves from foster homes to group homes before being spat out of the system as an adult. Mama’s boy is brutish and uncaring, but so is the only world he knows. Pitiful yet despicable, lonely yet abhorrent, the narrator’s situation is bleak, and made bleaker still by his certainty that life is out to get him. Interrupting a string of failed hook-ups and minor crimes comes Mama’s Boy’s discovery of his mother’s new location. He moves to the town she lives in, tries to fake respectability by lying his way into a job and taking advantage of every person he comes across, but when the two finally meet, things don’t quite go as expected.

A discombobulating blend of macabre humour and human tragedy, Mama’s Boy is a meditation on trauma, pain, loneliness, and the reasons behind — and consequences of — one man’s inability to take responsibility for his own actions.

X plus Y:

Where to start? Jack Kerouac’s On the Road mixed with Chuck Palahniuk’s Choke, or Ted Bundy crossed with Mickey Mouse, or Anakana Schofield’s Martin John, 2Pac’s “Dear Mama” and Last Exit to Brooklyn by Hubert Selby Junior all stuffed into the balaclava that’s about to whack you round the head. - alllitup.ca/Blog/2018/First-Fiction-Friday-Mama-s-Boy#topofpostcontent

Should we care about the company we keep in fiction?

In recent years there have been at least a couple of prominent instances of Canadian (at least for prize purposes) novels where the protagonist’s moral character became an issue. Claire Messud had to defend her character, Nora, from The Woman Upstairs, from an interviewer who said she wouldn’t want to be friends with her. This led to a media debate over the question of likability in fiction, with the strong consensus, at least among literary types, being that it shouldn’t matter and that, in particular, it shouldn’t be a criticism levelled at female characters.

This last point may be of particular significance, as a few years later it was Nino Ricci’s turn in front of a tribunal for his novel Sleep. It seemed that every reviewer of that book had to take a kick or two at failing academic David Pace. His crime? Sleeping around. This would not do, and whether it was the result of honestly held moral scruples or just virtue signalling to the masses, Sleep had to be held accountable.

I couldn’t help thinking of these two cases when reading David Goudreault’s Mama’s Boy (a translation by JC Sutcliffe of La bête à sa mere). The narrator—who adopts different names throughout the novel—is a thoroughly awful person whose political incorrectness is the least of his legion faults. As a user and abuser of women he puts David Pace to shame. And yet he is likable: a contemporary version of the charming rogue or picaro scamming his way through various satirical misadventures. Even in these censorious times, when outrage has all but entirely replaced criticism, it would be hard to imagine a reviewer saying they didn’t enjoy Mama’s Boy because the narrator is a bad man.

Tone is obviously a big part of the difference. Mama’s Boy is a comic novel: the story of an Untermensch whose delusions of grandeur and superiority are meant to provoke laughter. It seems everything the narrator deems useful to know is something he’s picked up in discussion forums on the internet (examples: “Women’s chests reveal a lot about their personality,” and “Greeks are very religious, it’s a genetic thing”). Internet learning has instilled in him the pride of the digitaldidact, which scorns the pretensions of formal education:

I do things intuitively, I’m a natural, as they say. Diplomas are only good for boosting talentless people’s self-esteem. It’s taxpayer-funded brainwashing, that’s all. Einstein didn’t do a PhD in relativity. No great author studied literature. Even the saints had no theological education. In life, you’ve either got it or you haven’t. And I’ve got it.Yet no matter how absurd his pretensions to being smarter, stronger, and better-looking than everybody else, it remains true that his “way of life” has forced him (in his own estimation) to become more “resourceful, creative, and practical.” But he also possesses the most essential quality for winning readers over: the ability to plead his case in an entertaining and articulate way.

Not surprisingly, this is another thing our antihero prides himself on. While he holds much of the world in contempt, he particularly despises the illiterates whom he frequently comes in contact with.

The language is in a desperate state among barmaids and other drug addicts. The government ought to come up with some program. Put reminders of grammar rules on cigarette packages maybe. It’s not like the rotten teeth and cancer photos put anyone off.That said, he has little use for actual literature. “Culture’s important,” he tells us as he steals the first couple of volumes from “a rather nice edition” of The Human Comedy, which he finds in an apartment he has broken into. The books, however, will be mainly useful for expanding his vocabulary: he has no intention of reading any more Balzac than what he can easily carry with him. Aside from this functionality, his other main use for literature is as jerk-off material. On his way to one such session he even visits the Quebec fiction section of a bookstore and rips the covers off “two promising novels by Nelly Arcan.” As a result of such a perversely directed self-education, his own name-dropping habit is an endless series of mangled cultural references and malapropisms. It’s all well documented, as he likes to say.

But passing moral judgment on the narrator, who is clearly a beast—even finding him a likeable or unlikable—is a trap. Like many such picaros living by their wits in a fallen world, he sees conventional morality as a form of hypocrisy that he is eager to expose. Judge him at your own risk.

The novel’s main motif for expressing moral hypocrisy comes through its discussion of the treatment of animals. We soon learn that the narrator, perhaps trying to fill in the squares on the psychopath checklist, kills cats. But he doesn’t think we can stand in judgement on him for this:

People’s crass hypocrisy exasperates me. Oh no, he killed a cat! So what, for fuck’s sake? We stuff our faces with dead animals all year long. Hundreds of them. Thousands. Tens of thousands during a lifetime. And of course tons of them are tortured during the process, raised in disgusting conditions, separated from their mothers and force-fed before being assassinated to feed human slugs. And I’m supposed to feel guilty about having killed my own cat, that I brought up and loved?The same feeling overtakes him later, while out on a date with a co-worker who insists on stuffing her face with a “steaming heap of protein.” This time he brings in some of his ersatz learning to help him out:

All animals are made to be eaten, it’s in the Bible and it’s well documented. We’re too hypocritical to eat our cats and dogs, but we could eat them, just like other animals. We should feed the poor with all the pets that get murdered at the SPCA. It would close the loop since it’s their own four-legged friends they’ve abandoned between houses. But when push comes to shove we don’t have the balls to follow through on our ideas.Given the blurring between the human and animal worlds implied in the way he expresses himself (cats and dogs are “assassinated” and “murdered”), it’s a pity that Mama’s Boy loses the “bête” from the French title. Identifying the narrator as the beast underscores how such arguments cut both ways. Animals are like us, and we are like them.

An attitude like this may make him seem unlikable, but after a bit of self-reinvention it lands the beast a job as an animal control officer with the SPCA, where he is led to meditate on various other hypocrisies in society’s treatment of animals. Going out on calls he reflects on how

There are so many abandoned animals. And no laws to condemn the irresponsible people who throw them out when they move house. It shows how stupid our legal system is. We have this whole setup to punish thieves who are just trying to survive, but do nothing about the bastards who abandon living creatures by the side of the road.Of course he is one such thief that the legal system (and every other system) is against, so there’s special pleading going on here. We get more of this when he considers the number of people with good homes waiting to adopt abandoned animals. This has a personal sting because he is himself an orphan raised by a series of families inadequate to the difficult task.

I learned that there was a bank of names of families willing to take in and care for injured animals. That disgusted me. Seriously, foster families for animals when there’s a shortage of them for humans? Worse still, the ones they par children in are poor or dangerous. I’d have been better off being born as a Bernese mountain dog.And the rest of us would have been better off too! This is another example of how everything that’s said in the book cuts at least two ways, and I think JC Sutcliffe’s lively translation does a great job capturing both the quickness of the story (which has to keep pace with the beast’s sex-and-drug fuelled hyperactivity) and the dense irony of the narrator’s boasting, which has more to it than just sending up the bully who is a coward and the nobody narcissist. Psychopaths and narcissists do have a power to charm and other qualities that impress us. They are performers we can’t help but watch.

As with many first-person antiheroes, most of what the beast says can and will be used against him later, but irony doesn’t diminish the force of his articles of complaint against society and his uttering of inconvenient truths. There is a slyness at work here that Goudreault handles marvellously. Because, despite being a comic figure, the beast is far from harmless. He is both a character with a long literary pedigree and a villain for our time: the troll with a million page views on his YouTube channel who grows stronger in the face of our outrage at his antics. We laugh because we take him literally but not seriously. I think by now we’ve learned that this is the wrong way around. A lot depends on minding the difference. - Alex Good

http://notesandqueries.ca/reviews/david-goudreaults-mamas-boy-reviewed-by-alex-good/

interview

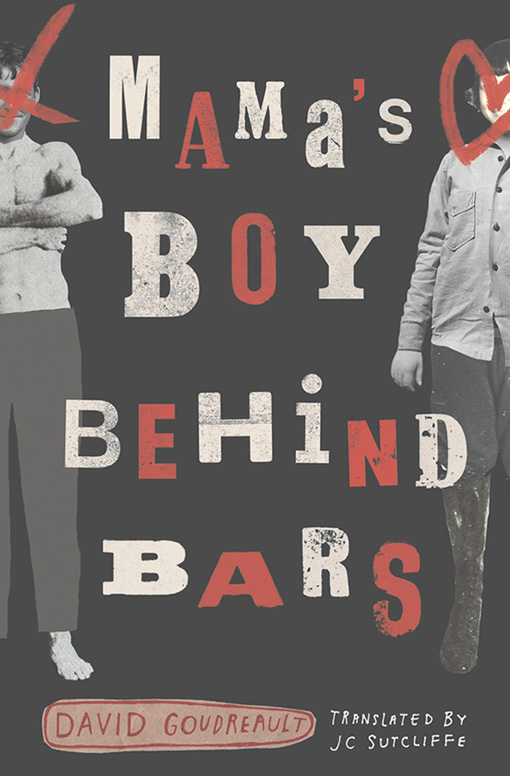

David Goudreault, Mama's Boy Behind Bars, Trans. by JC Sutcliffe, Book*hug, 2019.

Now I've killed another person. I'm a serial killer. Sure, two people is hardly serial, but it's a good start. I'm still young. Who knows where opportunities might lead me? Opportunity makes the thief, or the murderer, or even the pastry chef. It's well documented.

Mama's Boy Behind Bars is the second book in David Goudreault's wildly successful and darkly funny Mama's Boy trilogy. Once again written with gritty humour in the form of a confession, Mama's Boy Behind Bars, picks up where the first book in the series left off.

Mama's Boy finds himself in jail following a tender and violent search for his long-lost mother. In an attempt to survive his incarceration, he sets out to make a name for himself in the prison and is desperate to achieve his ambition of joining the ranks of the hardcore criminals. But things get wildly complicated when he falls in love with a prison guard. Can Mama's Boy juggle love and crime?

“Another essential work for anyone who wants to clearly see the things our society would rather keep hidden, the things that so clearly reveal who we are.” —info-culture.bizMama's Boy Behind Bars is the second book in David Goudreault's wildly successful and darkly funny Mama's Boy trilogy. Once again written with gritty humour in the form of a confession, Mama's Boy Behind Bars, picks up where the first book in the series left off.

Mama's Boy finds himself in jail following a tender and violent search for his long-lost mother. In an attempt to survive his incarceration, he sets out to make a name for himself in the prison and is desperate to achieve his ambition of joining the ranks of the hardcore criminals. But things get wildly complicated when he falls in love with a prison guard. Can Mama's Boy juggle love and crime?

“Mama’s Boy Behind Bars is, without question, even better than Mama’s Boy: delicious observations, hard-hitting humour, a majestic style, and a sense of rhythm that will make many more experienced authors envious.” —Huffington Post Québec

David Goudreault is a novelist, poet and songwriter. He was the first Quebecer to win the World Cup of Slam Poetry in Paris, France. David leads creative workshops in schools and detention centres across Quebec—including the northern communities of Nunavik—and in France. He has received a number of prizes, including Quebec’s Medal of the National Assembly for his artistic achievements and social involvement and the Grand Prix littéraire Archambault for his first novel, La Bête à sa mère (Mama’s Boy). He is also the author of Le bête a sa cage and Abattre la bête, both of which will appear in English translation from Book*hug. He lives in Sherbrooke, Quebec.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.