Kimberly Campanello, MOTHERBABYHOME, Zimzalla, 2019.

www.kimberlycampanello.com/motherbabyhome

The St Mary’s Mother and Baby Home was run by the Bon Secours Sisters on behalf of the Irish State to house unmarried mothers and their children. The location of the graves of 796 infants and children who died in the Home between 1926 and 1961 is unknown, though local knowledge, the research of local historian Catherine Corless, and recent excavations point to a field near the old site of the Home, as well as the likelihood that some children were illegally adopted. International media attention in 2014 led to the Irish government’s Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes, which is still underway.

MOTHERBABYHOME is a 796-page ‘report’ comprising conceptual and visual poetry. An excavation of voices, the poems are composed entirely of text taken from historical archives and contemporary sources related to the Home.

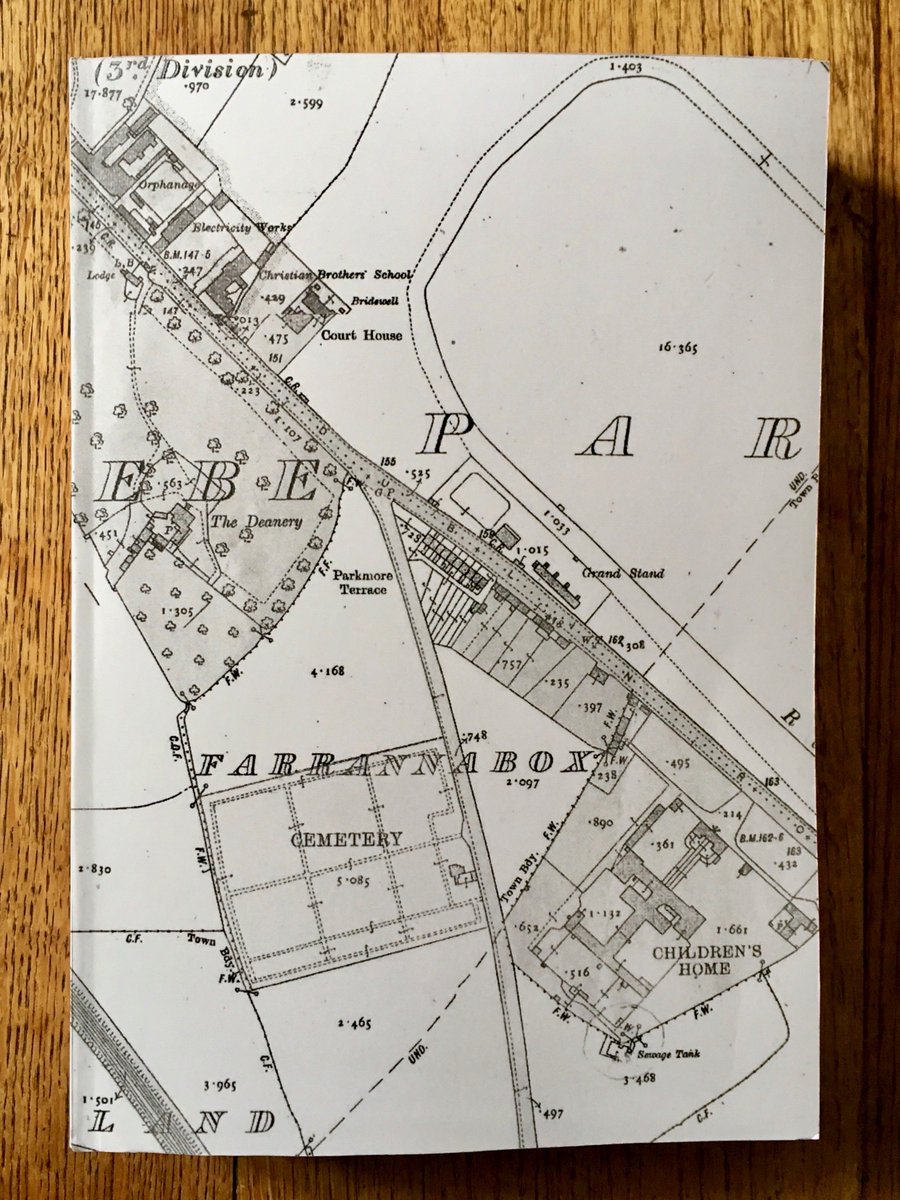

My latest publication, MOTHERBABYHOME, is a 796-page “report” comprised of conceptual and visual poetry about the St Mary’s Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, Co. Galway. MOTHERBABYHOME is an excavation of voices: the poems are composed entirely of text taken from historical archives, contemporary media, and other sources related to the Home, including files given to me by Catherine Corless.

The source material dates from the construction of the building in 1841 as a workhouse to February 17th, 2019, when the Commission’s final report was due. The 796 poems are printed on transparent vellum and held in a handmade oak box. MOTHERBABYHOME is also available in a reader’s edition book.

When the Tuam story broke, I felt that the children and women who had lived, worked, and died at St Mary’s had quite literally been submerged in the landscape and archive of the Home. The physicality of the language on the page felt vital to me, as bodily autonomy was what these women and children were denied.

I began working with the emerging textual material that the story produced, intervening in, exposing, and clarifying the unfurling text as it appeared in the press and in the archive. This included reactions that sought to undermine the truth as it came out, suggesting the stories were a kind of “Catholic bashing”. I set up a Tuam Mother and Baby Home Google alert to gather the material more systematically. I soon realised I was going to need to write 796 pages as writing a single poem about this catastrophic and extraordinary situation felt insufficient. As a poet, I am preoccupied by these questions: what does it mean to write poetry in the face of human brutality and destruction? What is poetry for in these contexts? Who is it for? What can it do? What form should it take? These questions have underpinned my approach to MOTHERBABYHOME.

There are three poets whose work has been a touchstone for me throughout the writing process: HD’s Trilogy (1945-46) on the second World War, written in London during the bombings; M Nourbese Philip’s Zong! (2008) about the Gregson vs Gilbert decision regarding the murder of more than 130 enslaved people by the crew of the slave ship Zong; and Thomas Kinsella’s Butcher’s Dozen (1972), which addresses the Widgery Report on Bloody Sunday.

HD re-installs the poet to the status of ritual maker, re-instating poetic language’s capacity to act as a lasting performative spell: “we take them\ [poems] with us beyond death” as poetry is “magic, indelibly stamped / on the atmosphere somewhere”. While HD’s work instills this sense of poetry’s vitality in the face of the horrors of war, I am also drawn to M Nourbese Philip and Thomas Kinsella’s borrowing from, questioning, and re-making of legal language.

Kinsella’s poetic intervention reveals and rejects the sleight of words found in the Widgery Report. Likewise, using language taken from the Gregson vs Gilbert decision on the murder of enslaved Africans in 1781, in Zong! Nourbese Philip re-shapes the actual words of the case. She reveals how the supposedly rational language of the law can be used to justify and enable enormous violence, and she shatters and re-forms this same legal language in order to remember the act of killing and to mourn the dead. Kinsella and Nourbese Philip caution us from thinking that there is anything inherent in the language of the law and institutions that will protect or save us.

The poet must lay bare this fact and reshape that language into something else, into something that can give an account of, mourn, love, and re-make. This understanding was vital for me in the development of MOTHERBABYHOME, which I hope goes some way toward a poetics of transformational accountability as practiced by HD, Kinsella and Nourbese Philip.

On the one hand, the language surrounding Tuam is mired in legalese, in administrative evasions, in the church and state’s contortions, backtracking and even plámásing. On the other, there is the absolute directness and clarity of the language of Catherine Corless, and increasingly, the shattering imagery of the survivors’ testimonies, the sharing of which, often for the first time, is its own kind of revolution in language. What I’m trying to do through the found and visual poems in MOTHERBABYHOME is bring these voices into direct contact with one another with heightened intensity and urgency. The final seventy pages are devoted to the word ‘delay’ - the unceasing delays - delays of the Commission’s reports; delays of investigations, excavations, and identifications; delays of admissions, apologies, and accountability. Delays of justice. Delays of love. - Kimberly Campanello

MOTHERBABYHOME memorialises the 796 infants and children who died at St Mary’s Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, Ireland. The location of their graves is unknown, though local knowledge, the research of local historian Catherine Corless, and recent excavations point to a field near the old site of the Home, as well as to the likelihood that some death records were falsified and the children were adopted without the knowledge or consent of their mothers. An excavation and radical repositioning of voices and landscape, the 796 poems are composed entirely of text taken from historical archives and contemporary sources related to the Home, including files given to the Campanello by Catherine Corless. Released by zimZalla Avant Objects on April 19, 2019, the poems are printed on transparent vellum and held in a handmade oak box. MOTHERBABYHOME is also available in a reader’s edition book. Kimberly Campanello will give a durational performance of the 796 poems at the Oonagh Young Gallery in Dublin on April 24, 2019. Extracts of MOTHERBABYHOME will be exhibited as part of Radical Landscapes: Innovation in Landscape and Language Art at the Plough Arts Centre in Devon (March 23 – April 20).

I became interested in working in this way (with archival material) when writing my second poetry collection Strange Country (on the sheela-na-gigs) because of the dearth of information on them. Strange Country uses found archival text from a range of antiquarian journals dating from the 19th century right through to mentions of the carvings in the Irish Times. Here is an example of a poem from that collection created in this way. In Strange Country, I also used archival methods to respond to the death of Savita Halapannavar in a poem called ‘Birthing Stone‘, which I talk about in an interview here.When the Tuam story broke in the mainstream press, I began working with the emerging textual material the story produced as I felt it resonated with the sheela-na-gigs and Savita, and because, as a feminist who was raised Catholic, I couldn’t really ignore it. I felt that the stories of these children and women, and the ‘material’ of those stories, children, and women had quite literally been submerged in the landscape and archive of Tuam. The materiality of it felt vital to me, as bodily autonomy was what these women and children were denied.

The first poem I did was this one. I began working further, intervening in, exposing, clarifying the unfurling material as it appeared in the press, including reactions that sought to undermine the truth coming out by suggesting the stories were a kind of ‘Catholic bashing’. I set up a Tuam Mother and Baby Home Google alert to gather the material more systematically. I soon realised I would have to do 796 pages, one for each child, and include a name, age, and death date on each page. The ‘single poem about the very bad terrible thing’ felt insufficient, perhaps has always been insufficient. I felt I was creating a monument, an intervention in the burgeoning archive, an archive that had been there all along (Catherine Corless uncovered it in all its detail). I felt that the archive was articulating itself like joints, bones.

In June 2015, I contacted Catherine Corless and sent her the thirty or so pages of the visual and conceptual poetry I had done. I explained my rationale for writing in this way, and asked if she thought it was a good idea, if she thought it was suitable. If she had said no, I probably would have stopped – I felt that it would defeat the purpose if the person responsible for the revelation didn’t find my sifting and shaping resonant. She understood what I was trying to do. I asked if I could meet her and use her files toward building this interventionary poetry memorial. She agreed, and I went to her home and scanned numerous files at her kitchen table. Since that day in July 2015, I have been working through those files and the expanding archive. The material in MOTHERBABYHOME runs up February 17, 2019, the date the Irish Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes was due to give its final report (delayed yet again). I finished the book on March 4th as a result of working through that recent material.

The road to completion of this book has been challenging not least because my niece was diagnosed with hydrocephalus in 2016. Because of my work on MOTHERBABYHOME, I knew exactly what that meant, and the death sentence this condition was, and indeed still is, for many children. That revelation froze me for almost a year and still pulls me up when I read the death certificates of these children, several of whom have hydrocephalus listed as their cause of death. At present, my niece is doing very well after four surgeries, and the delay meant I could include so much more material, including the voices of survivors that began to emerge so clearly in the past two years. - Kimberly Campanello

Kimberly Campanello is programme leader for creative writing and a member of the Poetry Centre in the School of English at the University of Leeds. On April 24th she will read the entirety of MOTHERBABYHOME between 5pm and 8pm at the Oonagh Young Gallery, 1 James Joyce Street, Dublin. All are welcome to come and go throughout the durational performance. More info www.zimzalla.co.uk

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.