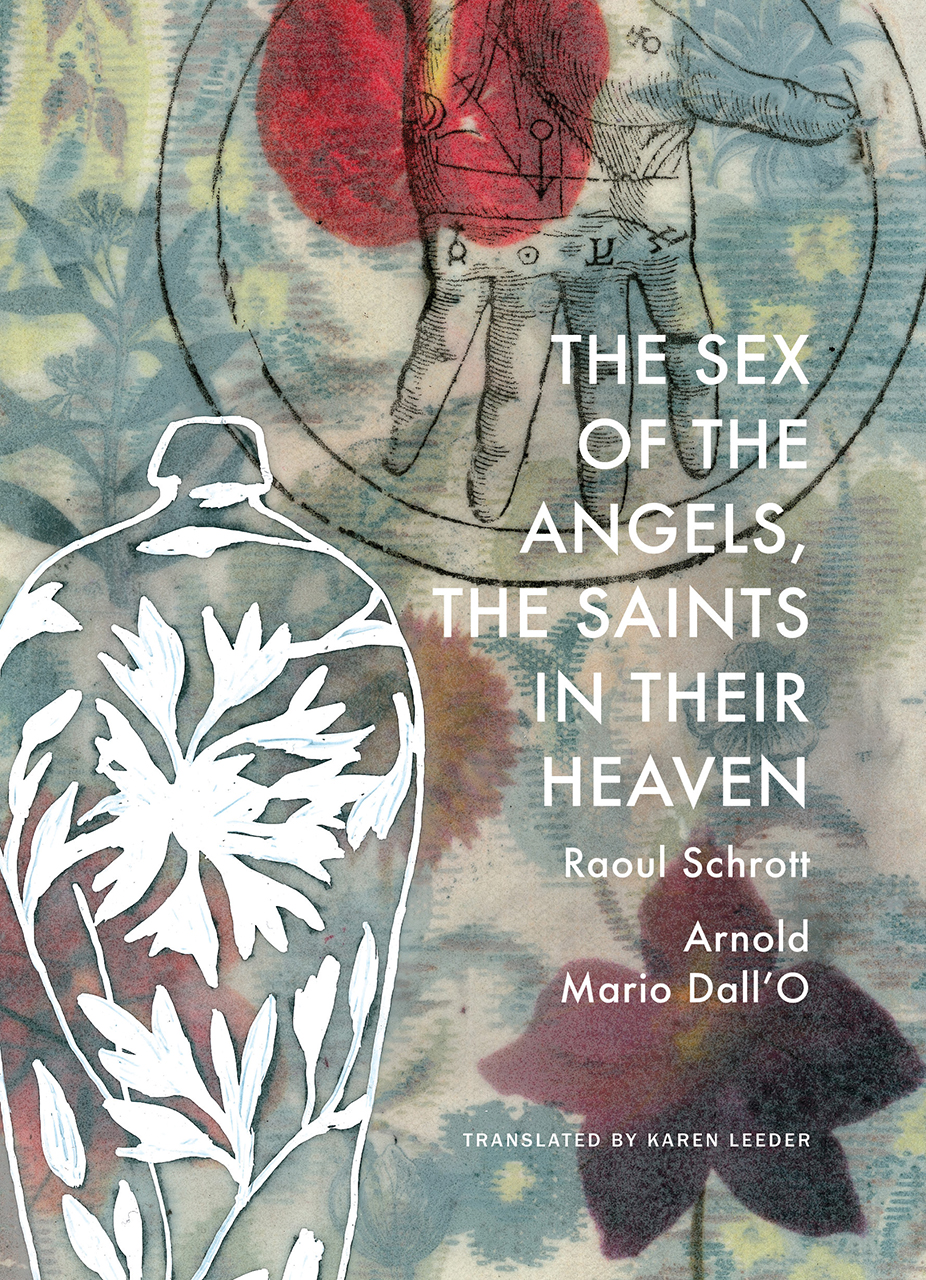

Raoul Schrott, The Sex of the Angels,

the Saints in their Heaven: A Breviary, Trans. by Karen Leeder,

Seagull Books, 2019. [2001.]

Breviaries, books of standard religious

readings for particular denominations, are a familiar genre with a

long pedigree. But you’ve definitely never seen a breviary like

this one. The Sex of the Angels is a playful, often ironic take on

the breviary in the form of a collection of letters that begins by

taking up early Christian cosmology and follows the Biblical

mutations of the angel from Babylon to the present day. As it goes

along, Raoul Schrott also weaves in a history which ranges from

ancient Greek legends of the origin of light to the medieval darkness

of the eclipse. But there is more going on here than meets the eye:

the letters are addressed to an unnamed “other” and chart the

course of an elusive affair. They are, we come to realize, a

declaration of love—or, more accurately, of yearning—but also a

far-reaching poetic essay which moves between etymological history,

anthropological anecdote, philosophy, and disquisition on the nature

of art. The text is supplemented by sumptuous illustrations by Arnold

Mario Dall’O that chart the stories of the saints, and the result

is a unique dialogue between literature and art: an extraordinary and

rare book about love.

Raoul Schrott’s book, translated from

the German, is a deeply philosophical story of the yearning of one

for another. I refrained from saying ‘person’ because there is no

clue relating the narrator to any life form. The book would make a

great conversation piece but given that no reviews can be found in

English and I suspect none in German either, I would have to wonder

why.

Possibly reviewers are shying away from

a book that takes so many viewpoints from so many sources. The

opening statement epitomises the outrageous affirmations that the

author makes. Clearly these are not meant to be true in fact but true

in the universe the author is defining. “Dionysius the Areopagite

was, I believe, the first to order the eternal night of the universe

with angels…to the outermost sphere, the dwelling reserved for God,

the primum mobile of the fixed stars, who assigned the Cherubim and

Seraphim” (1). This reference is from the first ‘chapter’ which

ends with a personal statement from the narrator to ‘you’ “simply

the most wonderful thing anyone could imagine. Would it embarrass you

terribly if I told you that you’re beautiful. Hardly, I suppose”

(4). This is the language of a potential lover.

The next chapter informs us on the

construction of angels, in particular the incredibly useful fact that

their wings attach to their feet (I did not know that, I confess!).

Full credit to the author for his use of language. Some of it, the

great bulk of it, is incredibly beautiful – “like the breath

between two sentences” (8), always there is mocking irony that is

never hurtful or vicious – when speaking of the ‘exact sciences’

the reference is to astrology. “What there is nowadays of angels

can be found under www.pfrr.alaska.edu/pfrr-/aurora” (8).

As the segments roll by each concludes

with some reference involving the narrator and his ‘lover’, and

one is therefore left with the most likely interpretation that this

elaborate book is simply a love poem. It is a poem that amasses one

outrageous idea after another, each building on the other and

developing towards an acceptance by the reader that this dream

universe might in truth exist. The whole concept is multi-faceted and

very clever.

The book is festooned with anecdotes

and illustrations, some barely comprehensible, most not at all. As

representatives of the world of art their quality to me anyway is

amateurish and devoid of interest. That having been said I think it

important to divulge that my knowledge of art, my ability to make

substantive judgments on the quality of an art piece or a collection

of such is limited to a personal like or dislike. A gut reaction if

you like/dislike. The cover calls the book “a unique dialogue

between literature and art: an extraordinary and rare book about

love” (inside dust cover). ‘Unique’ and ‘extraordinary’

resonate with me.

One cannot leave this book without

asking, “What, then, is an angel?” and the answer is given over

many pages of extraordinarily beautiful prose, but summed up in, “An

angel is nothing but the personified meaning of the questions we ask”

(106). What a let down! What images of spectres with wings of

gossamer sprouting from ankles have crashed to the dust? The author

continues:

In the gloom the gold gathers light

against the coming of the night. Words, nothing but words, you see;

the necessity of angels consist in being a metaphor for what is not

revealed; the light that cannot be named; already halfway to the

darkness of the solar eclipse that will happen soon…shadow-side of

God, the dark side that he turns towards humankind (110 – 111)

Many readers will gain much from

reading this book. It is most unlikely that what the book reveals to

me will be revealed to you, but what you take from the book will be

equally valuable. - Ian Lipkequeenslandreviewerscollective.wordpress.com/2019/03/12/the-sex-of-the-angels-the-saints-in-their-heaven-by-raoul-schrott/

If absence makes the heart grow

stronger, absence tinged with the uncertainty of love returned can

lead the heart and the imagination to wander into realms beyond the

merely mortal. To contemplate romantic perfection. To be filled with

a longing for something that may no longer exist. To attempt to

counter the earthly with the heavenly. To trust in angels.

The wonderfully titled The Sex of the

Angels, The Saints in their Heaven is essentially a series of

missives from a lovelorn poet to a mysterious red-haired beauty from

whom he has been separated by time, distance and, perhaps, some

recklessness on his part. He is writing from County Cork in the south

of Ireland, a place which is not his home, where he is exiled, or has

exiled himself, sending into the nightly blackness a chain of love

letters ever so loosely disguised as a sensual, passionate and mildly

profane angelology accompanied by miniaturized hagiographies.

Originally published in German in 2001, this extraordinary work by

Austrian writer Raoul Schrott, with its arresting illustrations by

Italian artist Arnold Mario Dall’O, is now available from the

inimitable Seagull Books in Karen Leeder’s delicately rendered

translation. Fictional, but not a conventional novel, essayistic, but

meditative in style, this book is an engaging blend of philosophy,

mythology, the classical sciences, saintly heroism, and earthbound

human romantic longing.

Our narrator begins, as one would

expect, with Dionysius the Areopagite—not the saint, but the fifth

century Syrian Neoplatonist who, writing in the name and style of his

sanctified predecessor was the first to craft a hierarchy of angels

and demons, a celestial stepladder to God for dark times. Within

Pseudo-Dionysius’ model of an angel-sustained universe, he locates

himself and his own angelic entity:

For Earth he chose only a single one,

which he placed in the lower arc of my ribs where I can feel it now,

hard as a little planet. I carry it with me (even now in the train it

keeps to its orbit) and sometimes I can see it before me: its mouth,

black brows and a storm of red hair over its freckles, an incarnation

of St. Elmo’s fire.

Captive and captivated, he writes as if

possessed, bringing the Aurora Borealis, Samuel Johnson, Greek and

Babylonian mythology and more into his musings as he tries to make

sense of his fate, this spell of infatuation under which he is

labouring. His thoughts never stray far from his beloved even though

his letters have yet to elicit a response. He is continues his

conversation into the silence, remembering their moments together. It

is not entirely clear how much he really has to build on, how much

they ever had, a quality that amplifies the sense of yearning:

Then as I sat next to you in the great

hall, I heard you more than saw you beside me; I listened to you;

wings folding shut. Do I bore you with all these sophistries and

sentimentalities? It is only because the post takes so damned long,

because I don’t know whether you will ever respond, not how;

because I must eke out the little that I have to create a picture of

you: little stones for a mosaic. The angels help me lay it out.

As he wanders the past and waits in the

present, meditating on the nature of the role of angels in the

affairs of humans, especially his own, our poet paints an image of a

windswept remoteness, an isolation actual and emotional. He

references local towns, harbours and natural features, like the aptly

named Mount Gabriel. The ocean is never far away, and water is a

major presence in his memories, his sense of loss, and much of the

mythology he calls on. His heartache is pervasive, and achingly

beautiful:I walk through the grass; it brushes

against my shoes. All is still, and I wish your voice was with me

now, whispered and low so that only I could hear it. Instead the moon

starts off on a soliloquy. Where it stands, stubbornly apart, is the

southwest and somewhere behind is where you are, as if only I had to

concentrate to see that far, peer over the curvature of the earth.

But where you are it is an hour later, I only wish I knew how to

catch up that hour.

- http://www.new-books-in-german.com/raoul-schrott

Raoul Schrott, The Desert of Lop, Trans. by Karen Leeder, Picador, 2004.

A poetic love story, a reminiscence of countries and cities: Raoul Schrott tells a story about a man and three women, about a little town in the desert and about travelling on other continents. Once a week Raoul Louper catches the bus to Cairo, and having arrived there he starts telling stories... He tells stories about love and the travels that have led him to and away from the three women in his life: Elif, Francesca and Arlette. He talks about single moments and about time slipping by. He remembers 'singing sands', quicksand, coastal strips and deserts. Again and again his thoughts return to the three women and to the countries where he used to live. Raoul Schrott has written a book in the spirit of Baricco or Calasso, a novella with a hundred and one chapters that tells us about love in its many guises, about the allure of the exotic and the new.

Raoul Schrott is one of Austria’s most successful and prolific writers: a polymath, translator from ancient languages, poet, novelist, dramatist, polemicist, academic, critic, and explorer. His most recent story 'The Silent Child' appeared in 2012 and the poetry collection The Art of Believing in Nothing followed in 2014. His most recent work is his 850-page verse epic First Earth (2016) and a book of essays Politics and Ideas (2018).

Because the distance that haunts him is

temporal, in more than one sense of the word, trusting the angels,

even if as he admits, he does not believe in them, has a certain

logic. A comfort.

Turning to John Scotus Eriugena, the

ninth century Irish theologian, best known for translating and

commenting on Pseudo-Dionysius, the narrator reflects on the inverted

balance existing between humans and their heavenly counterparts:

the angel finds its form within

humankind through the spirit (intellectus) of the angel that is in

the man; and man comes into being in the angel through the spirit of

humankind within him and so on and so forth for all eternity without

a single Amen being granted to us in Eriugenia’s scholastic

permutations. We are nothing but the imaginings of angels; and angels

exist only in our thoughts: that is our paradox not theirs.

He has entrusted his love and his

beloved to the care of angels, to hold her for him in their thoughts.

And yet, as her own distinction from the angels becomes less clear in

his letters, one has to wonder how much she has begun to exist only

in his thoughts. If she, in her epistolary silence is possibly not

thinking of him, what existential questions does that raise? For him?

For any of us who has ever loved hopelessly another who will never

return our affection? At heart, he knows, it seems.

And: no, I am not writing for writing’s

sake; no, if my letters were in any way beautiful, there were so only

on account of you; no, they are not complete in themselves; all they

do is beg for the answer and conceal best they can the question (they

tiptoe in stealth as I know they are trespassing on your territory).

No, your cheeks were so warm that it felt as if I could have woken up

next to you; no, there is nothing that could possibly dis-appoint you

from the rank of the angels; no, the Amores will never run out of

arrows, although I make a rather unholy Sebastian; and no, the angels

will not wear themselves out with words; writing to you brought at

least a few hours relief, then you started up again humming in my

ears.

The Sex of the Angels, The Saints in

Their Heavens reads like an extended meditative conversational prose

poem, a playful interplay between earth and the heavens, grounded in

the inescapable humanness of romantic love. The rich illustrations

and micro biographies of the lives and martyrdom of the saints

accompanying the text work together to form a running commentary on

the interrelationship between love, spirituality, literature and art.

This book could almost be, if one didn’t know better, the work of

the angels themselves. - roughghosts.com/2019/04/23/summoning-the-celestial-sex-of-the-angels-the-saints-in-their-heaven-by-raoul-schrott/

extract:

On the only stretch of road that runs

straight along by the river, I sometimes turn the headlights off so

that I drive for a second or two in the dark and see the earth

turning towards the night. From the hill, and from the house then,

the earth lies below me; the sea its stage, the stars extras, and

beyond the clouds a handful of actors waiting for their cue to enter.

Each one I give a different prompt: they always make a decent fist of

it. In the orchestra pit between the islands the wind slowly tunes

up; the beam of the lighthouse flashes the scenery before one’s

eyes every five seconds, but audience there is none. The rows of

seats are empty. I walk through the grass; it brushes against my

shoes. All is still, and I wish your voice was with me now, whispered

and low so that only I could hear it. Instead the moon starts off on

a soliloquy. Where it stands, stubbornly apart, is the southwest and

somewhere behind is where you are, as if I only had to concentrate to

see that far, peer over the curvature of the earth. But where you are

it is an hour later, I only wish I knew how to catch up that hour.

- http://www.new-books-in-german.com/raoul-schrott

Raoul Schrott, The Desert of Lop, Trans. by Karen Leeder, Picador, 2004.

A poetic love story, a reminiscence of countries and cities: Raoul Schrott tells a story about a man and three women, about a little town in the desert and about travelling on other continents. Once a week Raoul Louper catches the bus to Cairo, and having arrived there he starts telling stories... He tells stories about love and the travels that have led him to and away from the three women in his life: Elif, Francesca and Arlette. He talks about single moments and about time slipping by. He remembers 'singing sands', quicksand, coastal strips and deserts. Again and again his thoughts return to the three women and to the countries where he used to live. Raoul Schrott has written a book in the spirit of Baricco or Calasso, a novella with a hundred and one chapters that tells us about love in its many guises, about the allure of the exotic and the new.

Raoul Schrott is one of Austria’s most successful and prolific writers: a polymath, translator from ancient languages, poet, novelist, dramatist, polemicist, academic, critic, and explorer. His most recent story 'The Silent Child' appeared in 2012 and the poetry collection The Art of Believing in Nothing followed in 2014. His most recent work is his 850-page verse epic First Earth (2016) and a book of essays Politics and Ideas (2018).

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.