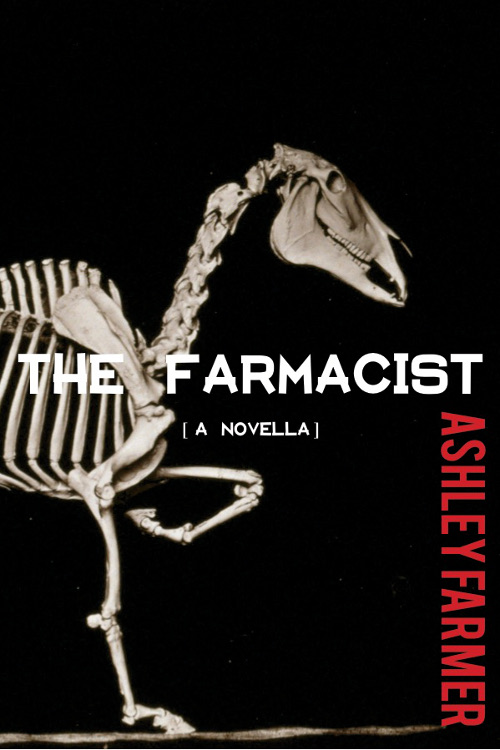

Ashley Farmer, The Farmacist, Jellyfish Highway Press, 2015.

www.ashleymfarmer.com/about.html

Step inside Ashley Farmer's America: a dizzying digital-agrarian-fever-dream fueled by virtual farmers plowing fallow fields for fake coins into the afterglow of evening, where Jesus Christ returns as a fallen satellite and the ghost of Ted Kennedy gets drunk on the lawn. In this wildly unconventional fictional universe, Farmer situates us at the intersections of work and play, the real and the imagined, the rural and the urban.THE FARMACIST is a hilariously heartbreaking romp through the cybernetic fields and streams and over to the imitation inns and taverns and on into your own neighborhood where the empire ends at the end of your street.

excerpt:

Sky zeroed. The trees are bananas. I lose myself beneath them, pluck them up by the trunks and shift and shake them. My farm Population 0 and yet I somehow feel among the juniper trees my old heart beating. I scratch my initials into bark like a math problem: AF + AF + a white chalk heart around it. I’m nowhere to be found and it’s hushed here without me. I throw a cocktail party but don’t show up. I buy an above ground pool but the water surface freezes like a screen. I install a carousel, but the sun ruins the music and protest notes sour from green to brown in midair. Maybe I dipped my toe in the wishing well and fell again. Maybe I’m digging out from beneath something. Maybe I’m in the town square reaping late-night consolation. I wear my laptop like a locket: inside are pictures of myself in miniature. I’ve held ground against droughts, against crumbling acres, against gifts of hammers and roses from mysterious neighbors. I’ve stayed small against seasons. Now I’ve vanished myself against reason.

Ashley Farmer's The Farmacist, a meditation on the Facebook game, Farm Town, explores the realm where the "real" world buffets the imagination, and the conscious mind courts the subconscious iterations of desire and distraction. It investigates the liminal space between log on and log off, between rural and urban. Whip smart and empathetic, The Farmicist is fiction crashing the lyric's slumber party, a reified shibboleth for the age of social media, all of it rendered beautifully, the poet's ear and the proser's eye working together to encapsulate and expound. Using the digital farm as a metaphor for the incredible shrinking American dream, Farmer gives her reader the rare experience of understanding human ambitions and aspirations as both futile and necessary. Don't ignore the invitation. -Christopher Kennedy It's rare to find bursts of prose so laden with the fruit of meaning: city and country, solitude and sociality, leisure and labor all get grafted together into a novel tree of Ashley Farmer's making. This book is often stunning in its vision of western life, the internet, and alienation-as she writes for us, "These dreams aren't even mine-I just idle in them." -Ken Baumann, author of EarthBound, Solip, & Say, Cut, Map It sounds nice when the speaker says it, that '[f]ailing at one world means nothing in another,' but as the stories in Ashley Farmer's captivating The Farmacist accrue, this proclamation becomes stretched tight, another reminder that how we honor / appropriate the past and thus how we choose to trudge into the future--beaten to a pulp or with our shovels held high--is the real key to driving out of this digitized pit we all slip into from time to time. I can't think of a better book for a new press to be running out of the gates with--one of the most daring and haunting collections I've had drop in my muddy mitts in a long, long while. -Tyler Gobble, author of More Wreck More Wreck The Farmacist cultivates survival, nostalgia, and community through surreal verve and melancholy tenderness. Splendid panoramas, ambitious toiling, flickers of Americana, a shared dream; Ashley Farmer illuminates the digital pastorals we rove and roam to connect, the vast pulsing heartlands we carry inside us. - Gina Keicher

The digital is often framed as a site of contagion—one can contract fatal viruses (or send them). One can suffer the pollution of good ol’ American values—the allure of exotic chrome and pixels from the Silicon Valley proving altogether too enticing. Indeed, the Valley itself was once good ol’ American farmland, before wresting technological eminence from Route 128 in Massachusetts. But one can also “go viral,” become contagion itself; one can colonize digital space as imaginative playground and bend its offerings to one’s own designs, just like a virus; one can even farm online. If the digital can be named any one thing, it is ever-replicating multivalence, which passes from vector to human vector, becoming at once a thing and its antithesis, simulacrum and simulacra, sanctuary from danger but also danger itself.

Ashley Farmer’s The Farmacist suggests by its title an affiliation with digital contagion—perhaps as an offering, a written prescription for our complicated diagnosis. Yet there is nothing prescriptive about its approach. Rather than tease a dichotomy between good and bad contagions, Farmer forces her readers to rethink both the charming idealism of a tech-utopia, as well as the privileges afforded “authenticity,” or the real. After all, does the computerized drip-irrigation of a farm render it unreal? And how much of Farm Town—an interactive digital pastoral available via Facebook—actually remains constrained within that fabricated digital?

At one point, Farmer’s protagonist is wearing a mask, the classical marker of (in)authenticity: “But when I pulled it off,” she says, “my real face was absent. In its place: an arrangement of hashtags. Put it on again.” There is no cathartic reveal, no affirmation of the real versus the unreal, or triumph of one over the other. There is not even a change of state—the mask returns to the face. There are no truths resting, hidden, behind it. Yet Farmer’s tale resists modernist nihilism as well, and the mask’s failure to unveil truth, health, salvation, does not fatally condemn its wearer, nor her world.

Every action in The Farmacist is hemmed in by margins of error, as characters seek “an approximation of heaven,” or are entreated to “walk towards me in beta” (emphases mine), though these margins are perhaps less boundaries and blankspaces than liminal incubators. Early on, the narrator insists that “This Bird of Paradise is not a bird,” a play on Ceci n’est pas une pipe; but where Magritte’s distinction is between pipe and mere image of a pipe, a Bird of Paradise was in fact never a bird, and has only ever borne passing, somewhat idiosyncratic resemblance to a bird. Whatever its image, it is a full organism unto itself; approximations of heaven and walks in beta are not only loose scrawls within the margins of error, but vibrant non-Euclidean spaces in their own right.

Of course, we cannot mistake this elaboration for pure celebration: “A bird is a bird,” writes Farmer, “if there are any left besides these seagulls mistaking parking lot for ocean.” Clouds, too, shift into pixel-governed geometry. And if the allegedly unreal—the images and the Birds of Paradise—are entities unto themselves, these are identities paradoxically dependent upon the pipe, the bird, the farm. Separate and whole but impossible without some other, brotherly whole.

The worlds within and without Farm Town are seeded into one another, inextricable, mediated. They are worlds of no dichotomies, no extremes. Of course, if these worlds suffer no fatal condemnations (only minor disillusions and farewells, which no worlds are without), they also cannot offer definitive answers; the pharmacy has no prescription for this.

Perhaps we must reconsider our etiology.

Narratives of the digital immediately call to mind their frontiers of contagion—the encroachment of the digital on our fair, pastoral lives. To focus on Farm Town, also a fair pastoral, casts doubt on the distinction between the life before and life after, that distinction which so critically undergirds our narrative trajectories, all frontiers and the famous (American) Dreams that both inspire and require them. For what reasons does one press the frontier and venture into digital escapism? Is it escapism if one ends up, within a reasonable margin of error, exactly where one began? If these frontiers require pure difference, what becomes of our narratives once one’s margins become tidal, sharing jetsam—or become tectonic, and actively overlapping? In The Farmacist, a robot attempts to connect to “nature,” to “neighbor,” and to “NASDAQ,” juxtapositions sardonically neoliberal. One of these is not like the other, an invader. But separating nature from NASDAQ crucially fails to address their many linkages, some of which are visible and concrete, some of which are imagined and visualized. These linkages complicate the etiology of our disease (if it is even a disease; perhaps this is not a disease but an image of a disease but simultaneously an entity entirely separate from disease) perhaps less an indication of contagion, and more a congregation of multiple, multiply constitutive valences.

After all, The Farmacist never suggests that it is about losing good ol’ American values, nor returning to them. The world beyond Farm Town filters through the narrative in apocalyptically tinged fragments, refrains of drought, of the barren West; Farm Town is never a devious ploy, and this story is not about lapsarian temptation. From its introduction in the prologue, it is already embarrassing, sentimental, “a commemorative Woody Guthrie plate bought by calling a 1-888 number on the TV screen”—an interesting anachronism, given Facebook’s plentiful, Web-based native advertising. If Farm Town’s commitment to nostalgia goes unrivaled, however, Farmer writes, “it is also a sincerity.” Nothing is “mere” artifice.

Why explore this? If there is no prescription, no solution, then what does The Farmacist stand on? Each chapter of Farmer’s novella earmarks how to live (or how we do live) in worlds that afford no clear prognoses. Success, empathy, earthquakes, commodities, prairies, violence, trees, malls, taxidermy, and failure teem on every page, congregate thick in every margin, until distinctions are not the point and authenticity is only a distraction and the digital and the embodied do not collapse into one another but snare each other with the rough pads of fingers at a keyboard, palms grasped around a plow handle:

Step inside Ashley Farmer's America: a dizzying digital-agrarian-fever-dream fueled by virtual farmers plowing fallow fields for fake coins into the afterglow of evening, where Jesus Christ returns as a fallen satellite and the ghost of Ted Kennedy gets drunk on the lawn. In this wildly unconventional fictional universe, Farmer situates us at the intersections of work and play, the real and the imagined, the rural and the urban.THE FARMACIST is a hilariously heartbreaking romp through the cybernetic fields and streams and over to the imitation inns and taverns and on into your own neighborhood where the empire ends at the end of your street.

excerpt:

Sky zeroed. The trees are bananas. I lose myself beneath them, pluck them up by the trunks and shift and shake them. My farm Population 0 and yet I somehow feel among the juniper trees my old heart beating. I scratch my initials into bark like a math problem: AF + AF + a white chalk heart around it. I’m nowhere to be found and it’s hushed here without me. I throw a cocktail party but don’t show up. I buy an above ground pool but the water surface freezes like a screen. I install a carousel, but the sun ruins the music and protest notes sour from green to brown in midair. Maybe I dipped my toe in the wishing well and fell again. Maybe I’m digging out from beneath something. Maybe I’m in the town square reaping late-night consolation. I wear my laptop like a locket: inside are pictures of myself in miniature. I’ve held ground against droughts, against crumbling acres, against gifts of hammers and roses from mysterious neighbors. I’ve stayed small against seasons. Now I’ve vanished myself against reason.

Ashley Farmer's The Farmacist, a meditation on the Facebook game, Farm Town, explores the realm where the "real" world buffets the imagination, and the conscious mind courts the subconscious iterations of desire and distraction. It investigates the liminal space between log on and log off, between rural and urban. Whip smart and empathetic, The Farmicist is fiction crashing the lyric's slumber party, a reified shibboleth for the age of social media, all of it rendered beautifully, the poet's ear and the proser's eye working together to encapsulate and expound. Using the digital farm as a metaphor for the incredible shrinking American dream, Farmer gives her reader the rare experience of understanding human ambitions and aspirations as both futile and necessary. Don't ignore the invitation. -Christopher Kennedy It's rare to find bursts of prose so laden with the fruit of meaning: city and country, solitude and sociality, leisure and labor all get grafted together into a novel tree of Ashley Farmer's making. This book is often stunning in its vision of western life, the internet, and alienation-as she writes for us, "These dreams aren't even mine-I just idle in them." -Ken Baumann, author of EarthBound, Solip, & Say, Cut, Map It sounds nice when the speaker says it, that '[f]ailing at one world means nothing in another,' but as the stories in Ashley Farmer's captivating The Farmacist accrue, this proclamation becomes stretched tight, another reminder that how we honor / appropriate the past and thus how we choose to trudge into the future--beaten to a pulp or with our shovels held high--is the real key to driving out of this digitized pit we all slip into from time to time. I can't think of a better book for a new press to be running out of the gates with--one of the most daring and haunting collections I've had drop in my muddy mitts in a long, long while. -Tyler Gobble, author of More Wreck More Wreck The Farmacist cultivates survival, nostalgia, and community through surreal verve and melancholy tenderness. Splendid panoramas, ambitious toiling, flickers of Americana, a shared dream; Ashley Farmer illuminates the digital pastorals we rove and roam to connect, the vast pulsing heartlands we carry inside us. - Gina Keicher

The digital is often framed as a site of contagion—one can contract fatal viruses (or send them). One can suffer the pollution of good ol’ American values—the allure of exotic chrome and pixels from the Silicon Valley proving altogether too enticing. Indeed, the Valley itself was once good ol’ American farmland, before wresting technological eminence from Route 128 in Massachusetts. But one can also “go viral,” become contagion itself; one can colonize digital space as imaginative playground and bend its offerings to one’s own designs, just like a virus; one can even farm online. If the digital can be named any one thing, it is ever-replicating multivalence, which passes from vector to human vector, becoming at once a thing and its antithesis, simulacrum and simulacra, sanctuary from danger but also danger itself.

Ashley Farmer’s The Farmacist suggests by its title an affiliation with digital contagion—perhaps as an offering, a written prescription for our complicated diagnosis. Yet there is nothing prescriptive about its approach. Rather than tease a dichotomy between good and bad contagions, Farmer forces her readers to rethink both the charming idealism of a tech-utopia, as well as the privileges afforded “authenticity,” or the real. After all, does the computerized drip-irrigation of a farm render it unreal? And how much of Farm Town—an interactive digital pastoral available via Facebook—actually remains constrained within that fabricated digital?

At one point, Farmer’s protagonist is wearing a mask, the classical marker of (in)authenticity: “But when I pulled it off,” she says, “my real face was absent. In its place: an arrangement of hashtags. Put it on again.” There is no cathartic reveal, no affirmation of the real versus the unreal, or triumph of one over the other. There is not even a change of state—the mask returns to the face. There are no truths resting, hidden, behind it. Yet Farmer’s tale resists modernist nihilism as well, and the mask’s failure to unveil truth, health, salvation, does not fatally condemn its wearer, nor her world.

Every action in The Farmacist is hemmed in by margins of error, as characters seek “an approximation of heaven,” or are entreated to “walk towards me in beta” (emphases mine), though these margins are perhaps less boundaries and blankspaces than liminal incubators. Early on, the narrator insists that “This Bird of Paradise is not a bird,” a play on Ceci n’est pas une pipe; but where Magritte’s distinction is between pipe and mere image of a pipe, a Bird of Paradise was in fact never a bird, and has only ever borne passing, somewhat idiosyncratic resemblance to a bird. Whatever its image, it is a full organism unto itself; approximations of heaven and walks in beta are not only loose scrawls within the margins of error, but vibrant non-Euclidean spaces in their own right.

Of course, we cannot mistake this elaboration for pure celebration: “A bird is a bird,” writes Farmer, “if there are any left besides these seagulls mistaking parking lot for ocean.” Clouds, too, shift into pixel-governed geometry. And if the allegedly unreal—the images and the Birds of Paradise—are entities unto themselves, these are identities paradoxically dependent upon the pipe, the bird, the farm. Separate and whole but impossible without some other, brotherly whole.

The worlds within and without Farm Town are seeded into one another, inextricable, mediated. They are worlds of no dichotomies, no extremes. Of course, if these worlds suffer no fatal condemnations (only minor disillusions and farewells, which no worlds are without), they also cannot offer definitive answers; the pharmacy has no prescription for this.

Perhaps we must reconsider our etiology.

Narratives of the digital immediately call to mind their frontiers of contagion—the encroachment of the digital on our fair, pastoral lives. To focus on Farm Town, also a fair pastoral, casts doubt on the distinction between the life before and life after, that distinction which so critically undergirds our narrative trajectories, all frontiers and the famous (American) Dreams that both inspire and require them. For what reasons does one press the frontier and venture into digital escapism? Is it escapism if one ends up, within a reasonable margin of error, exactly where one began? If these frontiers require pure difference, what becomes of our narratives once one’s margins become tidal, sharing jetsam—or become tectonic, and actively overlapping? In The Farmacist, a robot attempts to connect to “nature,” to “neighbor,” and to “NASDAQ,” juxtapositions sardonically neoliberal. One of these is not like the other, an invader. But separating nature from NASDAQ crucially fails to address their many linkages, some of which are visible and concrete, some of which are imagined and visualized. These linkages complicate the etiology of our disease (if it is even a disease; perhaps this is not a disease but an image of a disease but simultaneously an entity entirely separate from disease) perhaps less an indication of contagion, and more a congregation of multiple, multiply constitutive valences.

After all, The Farmacist never suggests that it is about losing good ol’ American values, nor returning to them. The world beyond Farm Town filters through the narrative in apocalyptically tinged fragments, refrains of drought, of the barren West; Farm Town is never a devious ploy, and this story is not about lapsarian temptation. From its introduction in the prologue, it is already embarrassing, sentimental, “a commemorative Woody Guthrie plate bought by calling a 1-888 number on the TV screen”—an interesting anachronism, given Facebook’s plentiful, Web-based native advertising. If Farm Town’s commitment to nostalgia goes unrivaled, however, Farmer writes, “it is also a sincerity.” Nothing is “mere” artifice.

Why explore this? If there is no prescription, no solution, then what does The Farmacist stand on? Each chapter of Farmer’s novella earmarks how to live (or how we do live) in worlds that afford no clear prognoses. Success, empathy, earthquakes, commodities, prairies, violence, trees, malls, taxidermy, and failure teem on every page, congregate thick in every margin, until distinctions are not the point and authenticity is only a distraction and the digital and the embodied do not collapse into one another but snare each other with the rough pads of fingers at a keyboard, palms grasped around a plow handle:

You are two places at once: your bed and your Farm Town plot. Blisters on your hands pop.

- Mika Kennedy Ashley Farmer’s work is unusual, beautifully so. In the author’s 2014 collection, Beside Myself, (from Pank’s Tiny Hardcore Press), characters would only briefly mention specifics of traditional narratives like place, yet the cascade of images and sentiments expressed by Farmer’s narrators created an overall stability in the book. Delicacy of strange images defines Farmer’s writing. With Beside Myself, short, difficult-to-define pieces straddle a line between flash fiction and poetry, Farmer established herself as a writer whose work is meant to be read holistically and experientially.

Such is also the case with Farmer’s new book, The Farmacist, from Jellyfish Highway Press. In The Farmacist, Farmer’s narrator struggles to untangle herself from the Facebook game, Farm Town, as her actual life unfolds around her. The juxtaposition of virtual versus real, Farmer’s mining of Farm Town for metaphor, and the duality of the narrator’s desires make The Farmacist, told in the author’s trademark short, mysterious, and glimmering prose.

The Farmacist begins with Farmer’s narrator addressing the omniscient presence looking over her shoulder—is this someone playing the game, the computer, or the reader? Farmer’s narrator is observed by all three. “You are with me,” she says, “though the acres are ending, all of it evaporating like anti-magic.” This sets the tone for a hyper-aware, meta-narrative.

There’s joy and irreverence in Farmer’s imagery each time she blends the vocabulary of Farm Town with that of the flesh-and-blood American experience. She says—

The farm makes you remember the Fourth of July, conjures the family portrait burning, the secret handshakes of senators, chrysanthemums on a banquet table for which you got paid a semi-wage, icy freeways or summer roads littered with locusts, and the ghost of Ted Kennedy drinking on the lawn.

Though at times the reader doesn’t have traditional narrative footholds, Farmer guides through a pastiche of things—both digital and worldly.

Farmer’s poetic voice shines in The Farmacist, and is demonstrated in her singular attention to details like sound. Lines like “Bundled, blue, and warm, I was their incident, their accident” underscore the broader scope of the story—one where a woman finds herself through digital creation–with the idea that meaning can be found anywhere, even in virtual realities. “I’ve stayed small against seasons,” the narrator says, speaking equally of farm and self. Farmer reminds us of the never-ending call from the digital world, emblematic of our deepest anxieties: “In bed, I will separate wheat from the chaff and make progress. I’ve added acres to my sleep and the profit from it: immeasurable.”

“I wait to go where I’m supposed to go,” says Farmer’s narrator—

some place ridiculous and waiting. Which is to say: I miss the world I knew. I embrace my worst impulse involving bed and drapes and sunny-sunny days. I realize some loves of my life are gone. I sense the farm is a long, fake waste.

As The Farmacist unfolds, its narrator loses control over both farm and reality. As she burns her candle at both ends, the narrative’s sense of panic—of not being able to stem the tide of digital problems—increases. Farmer’s narrator complicates her story (interestingly) by inserting philosophical ideals into the story. She runs Freud by her farm, and Jung. Her parents. As she brings the real world and points of view about the nature of existence into the same realm as the digital farm, we see how it is both absurd and absurdly important. Farmer’s work is sly commentary on the way we give away our power to computers, their feigned significance. She says, “I’m surrounded: chemical light sonnets and armies of alarms on a single block.”

“Failing at one world means nothing in another,” Farmer’s narrator says in a chapter called “Daily Lottery.” Though her digital farm is analogous to so many things that take up our attention, Farmer makes The Farmacist theater of the absurd in the digital age. Yes, this is a book about a Facebook game. But the author proves it’s a book about a Facebook game with something to say about humanity. - Heather Scott Partington

Like me, you may only know Farm Town as a Facebook app you blocked the moment you got an invite. But no prior knowledge is needed to lap up the irony, satire, and poetry of Ashley Farmer’s novella The Farmacist. The book—which could just as easily be called a novella-in-flash as a collection of prose poems—explores the pastoral and the digital world. And in turn, it explores a world of disconnection: “You flick a key and pixels contract, the bright sample images more resonant than exact, more compelling than fact, and all of it edited to the hilt.”

But Farmer infuses the serious with a good dose of humor—“Hit ‘Like’ If You Love Your Mother”—and the writing is equal parts wit and terror translated through fine poetic prose. The speaker laments, “I never thought my parents’ avatars would die.” In a world where, “Your body is 100% water and 5% download error,” Harry Houdini, Sigmund Freud, the Devil, and the reoccurring Dr. Doomsday and Aluminum Head visit Farm Town. And our speaker, planted in the real world—in the bathroom, looking out the window—is always returning to the farm, which “reminds me in the ribs the clocks changed for daylight savings, winter greening into spring.”

In Farm Town, “You toil hungry and broke and harvest 10,000 mango trees only to discover they’re worth less than a single patch of lavender. Your animals can’t breed or reproduce and you can’t slaughter them. They stand there purgatoried. They wait to be moved by the electric current that is you.” But Farmer reminds us that in the real world, we might find ourselves in a shitty bar in front of a game of Photohunt playing, “addition or subtraction of body parts and black straps and wisps of hair on naked women. I’m foolish but not so easily fooled: in one photo she’s whole, in the other incomplete.”

I found myself laughing and shuddering and starting whole passages over just to laugh and shudder again. The first release from Jellyfish Highway, The Farmacist is a solid start for a promising press.

- Christy Crutchfield

Following in the footsteps of literary speculative fiction writers, Farmer repeatedly questions the distinction between the natural and the manmade. In the novella, she is able to routinely alternate between genuine rural imagery and the computerized pastoral that comprises Farm Town: “I’m exiting through the field of wheat. I’m scratching the head of each well-tempered sheep as it grazes forever on my tender patch of lawn.” Elsewhere, the distinction between the “real” and the computerized is often subtle; Farmer’s work demands constant attention. Likewise, in chapters like “Overheard in the Market Place,” there is no delineation, the situation Farmer describes is applicable to both the real and the virtual. Parallels with Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? are difficult to avoid here, especially between the tenderness with which the protagonists of both works care for their mechanized livestock. The extent to which we invest ourselves emotionally in things that aren’t real is generally grounds for well-deserved derision, but Farmer seems to cast an empathic eye toward her narrator, a young female ostensibly from a farming family. Although Farmer’s narrator is one of the few constants throughout the novel, her presence is all but lost in some of the more opaque chapters. Instead of unilaterally condemning our capacity for being distracted, Farmer is able to probe what the ramifications of these distractions are, and how they sever our relationships with others. The density of her work follows Chekhov’s old dictum that nothing be wasted; her choices are deliberate. The compacted abstractions don’t make for the easiest read, but it’s apparent that her decisions are anything but arbitrary.

It would be easy to fall back on traditional pastoral tropes, to eulogize the absence of green fields and traditional farming methods to a technologically hyperliterate readership. Romanticizing farm life for a largely urban readership would be picking at low-hanging fruit, but Farmer avoids falling into clichés. She’s able to blur the distinction between urban and rural in subtle ways, referring to palm trees as being built to bend rather than break, arguing that it was “how they were made,” and elsewhere seamlessly blending nature with NASDAQ and the NYSE with Walt Whitman. She understands the ways in which collective nostalgia for the pastoral can be exploited and distorted, of the irony inherent in advertisements for a Woody Guthrie commemorative plate or of “This Land is Your Land” being played through a boombox.

Nevertheless, The Farmacist is still essentially an ode to what it means to be alone in a crowd: the 21st century, already oversaturated with irony, faces the contradiction that technology, with its capacity for bringing us closer together, also possesses the ability to isolate us in hitherto unseen ways. Internet escapism provides solace to the extent that, in Farmer’s words, “failing at this world means nothing in another” but Farm Town only serves to further isolate the protagonist. At one point, Farmer refers to her farm as a tabula rasa. The ability to modify one’s identity online could be seen as liberating, but Farmer is preoccupied with the same problem that both postmodernists and modernists like Fernando Pessoa spent their entire lives worrying about: be myself? Which one? Indeed, in a section entitled Masks, the narrator remarks, “But when I pulld [the mask] off, my real face was absent. In its place: an arrangement of hashtags.” These two sections, which follow each other, are typical of Farmer’s work. The connections are tangential, but purposefully so, a similar thread follows through most chapters.

Even though some of the ideas that Farmer engages are not specific to 21st century life, she doesn’t hesitate in grappling with more complex ideas about our relationship with technology. There is a certain danger when representations of objects appear more real than the objects themselves, of when life imitates technology: “I buy an above ground pool but the water surface freezes like a screen,” and elsewhere compares a river’s breath to the broken needle of a record player. The notion of apple-flavored candy tasting more like an apple than the fruit itself or the phenomenon of war and atrocity feeling “like a video game” represents a very specific form of alienation that Farmer’s generation was perhaps the first to experience, and the nuance with which she handles this phenomenon is particularly impressive.

It’s tempting to read The Farmacist in one sitting, but the wealth of ideas and the relative lack of a linear plot mean that the novella is better appreciated with some amount of patience. Each meditation provokes discussion in its own right, and they vary widely: One section entails only, “Keep your heart in the dirt and the dirt in your heart,” while another is a sort of love letter to Venus from the perspective of Earth. It’s easy to wade through ideas on the American Dream, America’s distinction between rural and urban, and the relationship between isolation and technology without adding to the conversation, but Farmer successfully approaches familiar themes in a completely unique and often quite poetic way, and is always building on the conversation rather than merely reiterating it. This is by no means an easy work, but it is an immensely rewarding one. - Jeremy Klemin

Ashley Farmer’s The Farmacist, the first book from Jellyfish Highway Press, came out yesterday. Christopher Kennedy’s blurb explains the book pretty well. He says, the book, “a meditation on the Facebook game, Farm Town, explores the realm where the ‘real’ world buffets the imagination,” and that it “is fiction crashing the lyric’s slumber party.” Nicely put.

At The Small Press Book Review, Christy Crutchfield wrote an awesome review of the book. She says, “Farmer infuses the serious with a good dose of humor – ‘Hit “Like” If You Love Your Mother’—and the writing is equal parts wit and terror translated through fine poetic prose.”

I got my copy yesterday. It’s a pocket-sized volume, perfect for reading in short bursts, but so engaging that you want to keep turning the pages for more. Is it really a novella, like the cover says? I guess it’s genre-busting enough to call it that. Justin Daugherty, who runs Jellyfish Highway, did a great job designing the book for elegance and readability. It makes me excited to see what’s next from his press. You can find out more about Jellyfish Highway and Ashley Farmer’s novella, The Farmacist, at their website.

Here’s an excerpt:

Gone to Waste

Purple hyacinths broadcast thirst: empty water droplets linger beside us. I materialize at the inn, beneath the severed heads of bucks to sip water standing up and watch pixilated ladies LOL and appear identical. I can’t tell myself apart any more than I might decipher how this town transmits me to me. There’s outside, and then there’s outside-outside: Saturday night at the reptile shop, the man beyond the Laundromat kicking a tree. These dreams aren’t even mine—I just idle in them. At the marketplace in the drunk of night, Dr. Doomsday’s demanding: are you lost or not? He means the opposite of friendship: he means economics. Just past midnight, I could beg a stranger home or hawk my crops, but I click myself into a tiny plot of rotting pumpkins only to identify the smooth, brown poverty as mine. A slab of river ends at my doorstep. No one I know knows how to move it. - Adam Robinson

Ashley Farmer, Beside Myself, TINY HARDCORE BOOKS, 2014.

from Beside Myself Gigantic #5--Talk Issue

Gigantic

PANK (Six) The Collagist

NAP

DIAGRAM

The Progressive

Juked

Ampersand Review

A girl drinks river water that gives her good advice but a bad reputation. A young woman’s job at a make-up counter ends in disaster. Car accidents and cornfields cause siblings to disappear while, up above, airplane banners advertise hair care products. Welcome to Beside Myself, Ashley Farmer's debut collection of short stories. These brief, lucid dreams illuminate the moment the familiar becomes strange and that split second before everything changes forever.

There are many reasons that an author would want to put a book–an actual physical object–into a reader’s hands, rather than just communicating data. Some books rebuff the notion that fiction is the same when it’s replicated digitally, downloaded, or speed-read. As I write this, the internet is abuzz over the new Spritz app, which promises to revolutionize reading by increasing the speed by which words can enter our consciousness. But does that miss something about the idea of the book? There are those who would make the case for a book being more than just information-delivery. A book like Ashley Farmer’s Beside Myself makes the case for slowing down. Rereading. Enjoying the entire experience of a book as a physical act.

Beside Myself is as much an art object as a collection of fiction. A beautiful thing to hold in your hand and consider as much as a container of profound thought. This new release from Tiny Hardcore Press is a bold move in a world of commercial, mass-produced fiction in the way that any good art challenges its viewer. This pocket-sized, carefully curated book is meant to be experienced; it is the kind of book you want to read in print and be seen reading. It asks its reader to actively approach its material.

Beside Myself is not just striking in terms of its tangible form. Farmer plays with ideas of a narrative line, even within each piece of fiction. Each short piece is a glimpse at something beautiful that doesn’t last, like a fish that swims close to the surface and then darts out of view. Plot lines are not consistently clear, but that’s not always the point. Farmer’s language is beautiful, captivating; her odd phrases strike notes of fragility, universality, and poetic beauty. In the title story, her narrator says,

Back then, a coat was something to be wrangled into. My profile was slack, slumping. The projection of my body toward the bus stop: airless. If people asked, you could say that my inclinations had been shaken out of me.

Back then the world was full of men in booths, producing tickets, pressing them into my palms.

Farmer’s characters guide her reader, giving us glimpses of the certainty of physical spaces and relationships: a town, a fair, a movie theater, the DMV. Brothers. She grounds us in physical detail and place. But links are in the shadows. Hard to catch. Slippery. Are these flash fiction pieces? Prose poems? Something in between? Farmer’s collection asks that we let go of the need to be grounded constantly.

Beside Myself opens with an invocation from James Tate: “God! This town is like a fairytale. Everywhere you turn is mystery and wonder. And I’m just a child playing cops and robbers. Please forgive me if I cry.” We see Farmer’s characters through the ripples on the surface, but even when details of the story are deliberately obscured, their emotional impact is clear. Farmer recalls settings, plot points, and motifs with just the hint of suggestion. Sometimes the connections are purely emotional, held together by the beauty of Farmer’s phrasing. “How wrong they were,” she says in “Coffin Water,” a story that speaks all at once to independence and parental expectation and our obsession with death. “[H]ow mistaken, those fathers bruised and troubled by their thirsty girls.” The ideas of bruising, death, and family relationships appear in many of the stories.

Where are we? When are we? As we read Farmer’s collection, we might not always know. But the stories themselves are bound together with emotional truth. Farmer writes oblique sentences that echo something familiar, as in the flash fiction piece “Tornado Warning,” when her narrator says, “[w]e wait like threads to be pulled.”

It’s not all obfuscation, though. Farmer uses clarity of place with specific purpose, often orienting the reader in such pedestrian venues as the DMV or the perfume counter at a department store. She concentrates on the ordinary transactions of commerce. These ordinary places are juxtaposed against transcendent descriptions and ephemeral sensations in the rest of her collection. “Limelight,” which starts with the clang of a cash register, ends with the line, “I sleep naked, unbuffered against the moon pretending myself into a pool that someone thirsty will arrive at and bend down into.” As a result of shifting from vague to specific and from pedestrian to ethereal, the physical details of the story—when they do appear—become more important to the reader. Farmer asks us to consider ideas of author’s intention, and our own reactions to her work.

From the moment you pick up this tiny book, you are a participant in the artistic process. You engage with these stories rather than reading them passively. Are the flash pieces in this book like poems? Some will say yes. But prose too is capable of terse beauty and mystery. Farmer writes with an economy of words and detail, and ultimately these are stories linked together by threads.

How do we read a book like Beside Myself? Like a gift. We study it from all sides, consider how it feels in our hands, read, consider, then read it again. It seems the point of Beside Myself is for us to ask questions. Farmer wants her reader to ask who her unnamed narrator is; she wants us to think about our own relationship to the work. The openness of this plot allows for each reader to bring him or herself to it. Beside Myself also raises larger questions about how we tell stories, and what form those stories take in their delivery. When we finish it, should the process be over, or should we dive back into the pond looking for answers? - Heather Scott Partington

In Beside Myself, Ashley Farmer tells 53 stories in 112 pages. Her debut collection of (mostly) flash fiction is fractured by design, relying on recurring images—neighborhood lawns at night, amusement parks, tunnels of love, grocery stores, TVs turned to the news, cosmetics counters at malls—to provide cohesion. On the surface, each story seems to take place in a recognizable reality, but then

Farmer scrapes at that realistic surface like a puppy at a door, wanting to be let outside to play.

The “reality” of Beside Myself is an off-kilter one, where a man who has fallen over can be unzipped to reveal a smaller man inside, “curled like a question mark.” Beside Myself is published by Tiny Hardcore, Roxane Gay’s independent press, and these stories are the sort of elliptical experimentations you’d expect when reading an issue of the often-excellent PANK, the literary journal also edited by Gay. Farmer’s stories has been published in a number of hip literary places—not only PANK, but also DIAGRAM, elimae, HOBART, Juked (where Farmer is an associate editor), etc.—which doesn’t surprise me.

Farmer’s best stories take at least a couple pages to tell. In “Coffin Water,” a warning from a father brings about thoughts of funerals and leaking caskets, finally reaching a moment where the young narrator realizes the gaps of knowledge in her father’s thinking about the world, and also in her own. In “DMV,” a driving test—particularly, some melted figurines on the dashboard—leads to a sort of spiritual awakening, the narrator realizing that there are “hands everywhere: one guiding the car like a toy, one waving us toward the bridge, another pointing to the bank of the river.” In “Where Everyone Is a Star” (the most conventional story here), a woman who has “been hired to guide children’s bodies through the air” sees her entire marriage crumble against the backdrop of a gymnastics competition. Elsewhere, a grandfather makes neon light, a tiger yearns first to be captured and then to be free, and a game show contestant’s answers become abstract (“I guessed ‘__’”).

Little in Beside Myself grips—or intends to grip—on a narrative level. Characters seldom have names and blur from one story to the next. To the degree that a reader recognizes him/herself in these pieces, it’s like stepping, as one of Farmer’s characters does, “through shards of [his/her] reflection.” Taken individually, each story is fascinating. But as a collection, its elusive quality occasionally wears me out. These stories keep slipping away, and Beside Myself resists sustained meaning; what does it add up to?

This might be Farmer’s foremost goal. Stars are referred to as “pushpins holding black fabric together.” A field is “a surface of water complicated by moonlight.” During sleep, “sheep count you.” The best moments remind the reader that reality can be a strange, startling place. “There is always so much surprise along the path to the barn,” Farmer writes, and Beside Myself introduces a writer who excels at finding all those surprises hidden in the dirt. - Benjamin Rybeck

Ashley Farmer’s Beside Myself has plenty of surreal imagery and an accelerated pace, but the collection feels oddly calm. It’s a book about introspection rather than bombshell plot twists. The characters are constantly turning the narrative inward, and there’s a sense of nostalgic distance in many stories—the kind of clarity that comes with time.

Consider the story “Summer Accident,” in which a girl vanishes, and the narrator notes that a neighbor’s “a black truck held the dent in its hood.” Later, a semi-truck is seen “dragging a segment of funhouse off,” and it appears that this narrator’s world is forever overshadowed by the threat of hit-and-run drivers. It’s a story about fear, uncertainty, and the eventual ability to cope. Farmer’s final lines in “Summer Accident” showcase a sense of clarity. She writes “The front yard oak tree rotted with sudden diseases. We gutted its trunk in the dark and packed the wound with wet cement. A scourge of thin, yellow worms writhed in the branches. If you stood back, the leaves moved. If you stepped across the road, the whole thing looked alive.” The physical distance from the tree becomes synonymous with chronological and emotional distance from the summer accident, the terror, and the obsessed anxiety. Through a change in perspective, the narrator can look at the grisly tree and remember its life rather than its death. It’s a symbolic mourning process that encapsulates weeks or months of grief through a simple step across the street, away from the source, away from the summer of tragedy.

This type of symbolic character meditation is common throughout Beside Myself. Take for example “The Light at the End of the Tunnel of Love,” in which the brief excursion through the tunnel, toward the light, explores both mistakes and forgiveness in the same instance. It’s a surreal look at what the character was, is, and could be. Meanwhile, many characters also grapple with a confused sense of self as they contemplate, trying to figure out how to make sense of the flash fiction snapshots they inhabit. While some characters achieve clarity, many underscore hesitation, and characters aren’t quite sure how to gain a fresh viewpoint on their rocky pasts. “Assembled” captures this idea overtly; the story opens with “It was tentative, how I assembled myself.” Eventually, the story progresses toward the final moment of disassembly. When the narrator removes her mask-like cosmetics, staring at herself in the mirror, she says “The raw face approximat[ed] one I recognized.”

In other cases, characters detach and seek distance from themselves, as is the case in the title story. Characters often need to dissociate to examine their own lives, looking for proof of worth or proof of self. There is hesitation in many stories, certainty in others, but the overall impression is a twisted game of character hide-and-seek, and there’s a certain delight every time the reader ‘finds’ the character—really finds her, in her most vulnerable moment.

In this way, Beside Myself is grounded in characterization, but there’s a yet another contemplative layer woven through the collection. While character is central to Farmer’s work, she also extends a friendly hand to readers, inviting them into the fold. Her stories are minimalistic, and she makes deliberate choices to hold certain things back. Faced with intentionally skeletal stories, readers superimpose their own flesh onto the narrative. Farmer relies on these audience preconceptions rather than fighting against them.

In many stories, the invitation is extended explicitly, using the second-person point of view. The “you” being addressed is often ghostly and abstract, and readers can imagine themselves filling in, interacting directly with the character. Readers always bring a piece of themselves to a book—that’s nothing new—what is exciting and refreshing is how comfortable and encouraging Farmer is with this fact. She doesn’t seek to control the narrative; she purposely leaves certain pieces fuzzy, letting the readers add their experiences into the mix. Beside Myself wants to you to get involved. It wants you to reflect, to feel, and to engage in dialogue with the characters—there are few monologues here. It’s an innovative collection that plays with character and narrative, encouraging readers to feel at home in its pages. You won’t be disappointed as long as you approach it with an open mind, willing to embrace occasional ambiguity. - James R. Gapinski

Beside Myself, Ashley Farmer’s debut story collection, is out March 3, 2014 from Tiny Hardcore Press. Farmer’s flash fiction surprises from story to story and from sentence to sentence, constantly asking the reader to re-evaluate impressions formed just a moment before. These stories are often surreal, but sometimes not; some are longer and more narrative; others are just a few sentences and focus on an image or scene. Whatever the case, the collection as a whole appeals to our desire to fantasize. The book begins with a shared fantasy, as two characters imagine a high school football game played out on the front lawn. In this way, even the stories that are not surreal convey the presence of imagination. In “The Ridge” the narrator remembers:My mother used to drive us up to The Ridge, a neighborhood that overlooked ours. My favorite house was a lavender cube with pink windows. My grown self flickered like heat in the kitchen. I imagine the owner imagined what I imagined: that she lived in the successful future.Fantasy, Farmer reminds us, is inescapable, even within the bounds of our real lives. In “Pink Water,” a woman talks about working at a cosmetics counter, selling “a pink mist that promised to erase anything the opposite of heavenly from one’s face,” which attracts hordes of hopeful women. “The Tunnel of Love” referenced in the first story reappears later in the collection. It remains a destination the narrator has only heard about, one she wants to visit but never reaches. “Still Life with Neighbor” is a story that turns out to be (spoiler alert) a collection of contradictory imaginings about a neighbor. As Farmer writes at the end: “There has never been a neighbor, but you think of him just the same.”

Though her stories are brief, they quickly establish an intimacy between the reader and their (usually) first person narrators. In the hands of anyone else, some of the subjects could be recognizable. A couple whose relationship is on its last legs transports a dying bat. A narrator describes her reaction to a girl she knew being killed by a car. A woman who works spotting kids at a gymnastics studio splits with her husband, who coaches there. She comments: “Dreamless nights, I imagined myself on the clearer side of the glass. An expert adult, even-pulsed, all filled up and watching only her own.” Farmer’s narrators indulge their urges to imagine, allowing the reader to as well. Like the stories themselves, the sentences that comprise them are beautiful, efficient, and odd. Reading them does not fall into the realm of normal experience. Each one is powerful enough to stand on its own:

“Then the June road vanished a girl I knew.”

“She was a memory so familiar that she became abstract if I considered her for more than a moment.”

“I sleep naked, unbuffered against the moon pretending myself into a pool that someone thirsty will arrive at and bend down to.”

Certainly some of Ashley Farmer’s lines could find themselves at home in poems, but these are stories. Some unfold from a surreal conceit (like a constantly burning fire) but in others the surreal simply creeps into a scene, part of the environment. For an instant, rain turns into naked, melting women falling from the sky, then a man faces another woman, this one disappointed and solid. Nature itself recoils from protesters, ivy withering at their assault.

These stories are unlike any flash I have ever read. They have the conviction of Lydia Davis shorts (rarely can an author pull off flash so short) and a linguistic inventiveness equal to that of Diane Williams. They are not fables. To me, they don’t seem quite like dreams, either. They are conscious fantasies, the kind you want to slip into when you are wide awake, reading. You will want to ration and reread these stories, giving each one a chance to settle and resettle in your mind. Reading these stories is like driving past a stranger’s window and imagining the lives behind it. They are perfect and exhilarating, filled with the promise of the impossible. - Sadye Teiser

I remember the first time I read Jo Randerson’s microfiction. I was on a bus, probably going to the job I held at the time as an after school carer in Thorndon, a neighborhood in Wellington. Thorndon is past the CBD, but only just, and sometimes in winter if I was feeling rushed or it was raining hard I would take the bus to get there, but Wellington is small and the bus ride from the bottom of Courtenay Place to the final stop at the train station is only about 15 minutes long. Anyway, I remember reading Jo’s book The Spit Children on the bus a couple of times that week and getting through four or five stories, maybe more, just in that bus ride. The first time or two I did this, I’d get out of the bus and be thinking about the last story I read, or maybe the most vibrant one, but never all of them. I’d lose at least 80% of what I read pretty much right after I’d read it. And it wasn’t just bus rides that would do this to me; it would happen any time I picked up Jo’s book.

Eventually, I started reading each story two, three, four times right in a row, back to back to back. If I was on the bus, I would spend the whole bus ride on just one or two stories. This was better, but I still wasn’t remembering everything. What was the problem? I wanted more from the worlds of the stories, more on the page, more from my imagination, more more. But it simply wasn’t there. I wasn’t going to find it because it wasn’t there for me to take. If I want to think about The Spit Children now, I go back to the book on my shelf. I can’t carry it around with me in my mind like I can with the stories from The Lottery or, The Adventures of James Harris, another short story collection I read and loved that same year. The Spit Children wasn’t meant to be read in the same way as The Lottery.

Microfiction isn’t meant to be mentally carried. In the way Google has taken the place of my childhood obsession with memorization, pocket-sized microfictions endeavor to remove my desire to preserve fictional worlds in my mind. I still carry my first impressions of Jane Eyre (age 15), The Secret Garden (age 8), King Bidgood’s in the Bathtub and He Won’t Get Out (age 3), despite the decades separating me from them. But there is a certain luxury in the microfiction: a back pocket-sized book meant to be picked up and carried with you like an external hard drive for your brain. Read Parker Tettleton or Lydia Davis and you’ll see what I mean. Stop thinking about it like a longer narrative, and the attraction grows.

Pick up almost any Tiny Hardcore Press title and not only will you feel this change in your brain as you read, you’ll feel it immediately in the shape of the book in your hand. These books are small and square, perfectly tailored to fit in your pants or your coat. The stories inside are a little bit weird and a little bit relatable. Ashley Farmer’s Beside Myself is no exception; her stories contain quick flashes of horror and siblings, relationships and occasional creatures from the black lagoon. They sit comfortably between xTx’s Normally Special and Brandi Wells’ Please Don’t Be Upset, filling equally important spaces in the external hard drive I now carry as a part of myself. - Carolyn DeCarlo

he end of the World.from “Diary of an Ex-Precedent”

As a pet, I crave personal connection from prose. I crave the type of prose that pushes boundaries and straddles the fence between poetic language and story telling. Farmer will bend you with her flash fiction collection, Beside Myself, with its woven four-part narrative full of accidents and beautiful little truths.

“Snow/ Sunrise/ Ambulance” gives a narrative oscillating between the gentleness of falling snow and the wears of the body after disaster, bringing haunting truth and beauty pulled through memory. “Tornado Warning” sets us up for chaos of the landscape complimented with particulars, the neighbor knotting his boat to a tree and the sky as it “rolls up its green belly.” This chaotic landscape brings us to a discombobulated perception of our surroundings, it could be winter or summer. At the end, we are left with a pseudostillness and pushing our identity as readers against text and landscape while compared to precious threads just waiting to be shown the world. In part two, “Where Everyone is a Star,” we rediscover language through the world of a gymnast teacher, bend bodies and push the limits of relationships, straining love. We are left with inevitability of gravity. “Brother(s)” delves into the multiplicity of not only siblings but of the self, with odd quirks and fits of rage, and little moments of tenderness that often times go unseen, revealing our bridges to ourselves and how to burn them down.

“Diary of an Ex-Precedent” allows us to dream with tributes to Reagan and the heart-warming images from space. We are woven into the narrative “our silver linings on our sleeves,” the readers assimilate into the narrative left to rediscover our childhood, our mistakes, and handed over to the simple and vast truths. We are just left to float, bending time, redefining our generation. We are momentously pulled into part four to memories of young girls at the beach rediscovering the body, as we are left dreaming of high school pulling our old memories out and scattering them across the floor and picking out the sun filled pieces to put up on the window sill to stay awhile, as the young girls transform from women to babies exposing their beauty and soft spots.

Each flash piece exposes a new side to itself giving each narrative many different faces, each like a field embedded with jewels or precious metals. Farmer’s narratives leave us pushing the idea of reader and narrator, forming a new relationship with the text and ourselves, leaving us to unearth memory and expose it silhouetted with detail. We invent the narrator of our own personal landscapes.

Beside Myself is dynamite, pushing beyond the cliché of a page-turner, needing to be read more than just twice. Farmer’s collection redefines prose, opening the door to not only how we interpret fiction but also how we interpret beauty, exposing the utter urgency of literature. A book we have all been looking for since we started dreaming. - Alexandra Gilliam

Ashley Farmer’s Beside Myself is all over the place. Its very (very) short stories are set in woods, near rivers, on the sets of game shows, in department stores, behind grocery stores at night, in traffic. These places feel simultaneously strange and familiar, the way they often do in real life. For as easy as it’d be to label a writer like Farmer “experimental” or “anti-realist,” it’s not like she doesn’t employ mimesis. There is a deeply representative quality to her writing, it’s just that she’s just particularly adept at representing seemingly boring things as they really are: Strange and unnatural, not boring at all, actually. It’s easy to forget all this weirdness if you’re surrounded by it daily and never drop acid, but one of the best things about Farmer’s book is its straightforward power to defamiliarize both the natural world and the endless unnaturalness we insist on imposing on it. A gymnastics studio in “Where Everyone is a Star,” one of the collection’s best stories, has “blatant yellowy walls” [63], and earlier, a “marble floor is bright flesh with blue veins so convincing you’d bend to kiss it if you weren’t clutching the wrist of distance itself” [47]. At the very least, this kind of descriptive power alerts you to the fact that the places we go have their own weight and character, determined daily by the material and spiritual gravity of the crowds who pass through them. Another thing that’s easy to forget.

More important than the places, though, are the people. Farmer’s characters, often inhabiting some spot between actor and speaker, body and voice, never seem complete, but this incompletion is intentional, and basically the tension that drives the whole collection. How can we know ourselves, let alone one another, when our selves are always shifting? There are lots of flashes of people, parts of them radiating throughout the text without ever quite cohering into a single knowable character. They seem defined more by this lack than by any recognizable feature, like a body that’s “more space than matter” [47], or the constant feeling of brushing up only against “the edges of others” [37]. Still, these images, stubbornly unfinished as they are, yield important insights in ways infinitely more interesting than just showing or telling. Instead, Farmer invents ways to present people’s contradictions and confusing, intriguing properties, like when she writes about the rich guy, object of a political protest, who turns out only to be a costume of a rich guy – “Beneath the padding: a smaller man, curled like a question mark” [18] – and reminds you that yes, of course the nominally powerful feel afflicted by – defined by, even – uncertainty, and the crushing awareness of their own insignificance. Just like the nominally powerless. Shapes of people and relationships recur and echo throughout Beside Myself — pairs of siblings, distant couples — suggesting that all of this uncertainty and incoherence might end up binding us together. An unnamed neighbor shows up in a few stories, and his ghostlike presence illustrates how easy it is to remain close to someone and still have to guess about who they are.

The collection’s title story, in which a woman sits in a movie theater and the boundary between herself and another person slowly evaporates, or gets revealed as a ruse, maybe best encapsulates the book’s optimistic orientation toward the problem of being a fractured, undone person. “We’re never the only ones” [35] the narrator insists, and the collection bears this out. Everyone’s in this together, even if (or because) it can be hard to tell who’s who, where your own self starts and others’ end. Farmer writes stories that are easy to read and often funny and, despite being comprised of syntaxes that don’t exist anywhere else, never sound arbitrary. Beside Myself reads like a calculated attempt at documenting people’s imprecision, and for that reason alone, it might be a good argument for experimental fiction’s practical potential. - Conley Wouters

From Literary Mothers Project More important than the places, though, are the people. Farmer’s characters, often inhabiting some spot between actor and speaker, body and voice, never seem complete, but this incompletion is intentional, and basically the tension that drives the whole collection. How can we know ourselves, let alone one another, when our selves are always shifting? There are lots of flashes of people, parts of them radiating throughout the text without ever quite cohering into a single knowable character. They seem defined more by this lack than by any recognizable feature, like a body that’s “more space than matter” [47], or the constant feeling of brushing up only against “the edges of others” [37]. Still, these images, stubbornly unfinished as they are, yield important insights in ways infinitely more interesting than just showing or telling. Instead, Farmer invents ways to present people’s contradictions and confusing, intriguing properties, like when she writes about the rich guy, object of a political protest, who turns out only to be a costume of a rich guy – “Beneath the padding: a smaller man, curled like a question mark” [18] – and reminds you that yes, of course the nominally powerful feel afflicted by – defined by, even – uncertainty, and the crushing awareness of their own insignificance. Just like the nominally powerless. Shapes of people and relationships recur and echo throughout Beside Myself — pairs of siblings, distant couples — suggesting that all of this uncertainty and incoherence might end up binding us together. An unnamed neighbor shows up in a few stories, and his ghostlike presence illustrates how easy it is to remain close to someone and still have to guess about who they are.

The collection’s title story, in which a woman sits in a movie theater and the boundary between herself and another person slowly evaporates, or gets revealed as a ruse, maybe best encapsulates the book’s optimistic orientation toward the problem of being a fractured, undone person. “We’re never the only ones” [35] the narrator insists, and the collection bears this out. Everyone’s in this together, even if (or because) it can be hard to tell who’s who, where your own self starts and others’ end. Farmer writes stories that are easy to read and often funny and, despite being comprised of syntaxes that don’t exist anywhere else, never sound arbitrary. Beside Myself reads like a calculated attempt at documenting people’s imprecision, and for that reason alone, it might be a good argument for experimental fiction’s practical potential. - Conley Wouters

From The Women

Noo #14

Everyday Genius

Hobart Online

Two Serious Ladies

Specter Magazine

Ovenbird Poetry

Jellyfish

Noo #14

Everyday Genius

Hobart Online

Two Serious Ladies

Specter Magazine

Ovenbird Poetry

Jellyfish

Selected Non-Fiction and Reviews

"Cat People"--FLAUNT MAGAZINE (Nine Lives Issue)

Book review of Gina Myers' HOLD IT DOWN at Small Press Book Review

Book review of Rosalie Morales Kearns' VIRGINS AND TRICKSTERS at Small Press Book Review Nano Fiction--State of Flash ("Strength of Flash")

Our Stories (interview with Adam Haslett)

PANK (Farm Town interview, conducted by J. Bradley)

PANK online (This Modern Writer series essay)

Salt Hill Journal (interview with Patrick Lawler)

The Sapling--Black Lawrence Review (Naropa conference profile)

"Cat People"--FLAUNT MAGAZINE (Nine Lives Issue)

Book review of Gina Myers' HOLD IT DOWN at Small Press Book Review

Book review of Rosalie Morales Kearns' VIRGINS AND TRICKSTERS at Small Press Book Review Nano Fiction--State of Flash ("Strength of Flash")

Our Stories (interview with Adam Haslett)

PANK (Farm Town interview, conducted by J. Bradley)

PANK online (This Modern Writer series essay)

Salt Hill Journal (interview with Patrick Lawler)

The Sapling--Black Lawrence Review (Naropa conference profile)

Ashley Farmer is the author of the poetry collection The Women (Civil Coping Mechanisms, forthcoming 2016), the story collection Beside Myself (PANK/Tiny Hardcore Press, 2014), and the chapbook Farm Town (Rust Belt Bindery, 2012). A former editor for publications like Atomica Magazine, Salt Hill Journal and others, she currently serves as an editor for Juked. Ashley resides in Louisville, Kentucky, with her husband, Ryan Ridge.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.