David Buuck, Site Cite City: Selected Prose Works 1999-2012, Futurepoem Books, 2015.

Read an Excerpt at TheVolta

buuckbarge.wordpress.com/

David Buuck works at the axis of performative and civic aims to make a narrative that is clarified the more it breaks down, as much through desire as by violent or revolutionary means. — Bhanu Kapil

In David Buuck’s Site Cite City, the detective novel meets the essay meeting the poem in prose, which, somewhere along the way, has already bisected machine language and passed through the byways of psychogeography, making for a text as mysterious and entertaining as it is activist and knowledgeable. An invaluable contribution to everything.— Renee Gladman

“Read this book and witness our totalizing Weltanschauung, where ideology is worldview—or is it the other way around?” —Mónica de la Torre

David Buuck and Juliana Spahr, An Army of Lovers, City Lights Publishers, 2013.

Table of Contents and the First Fourteen Pages of An Army of Lovers (PDF)

excerpt

excerpt 2 (pdf)

An Army of Lovers begins with the story of two poets, Demented Panda and Koki, united in their desire to write politically engaged poetry at a time when poetry seems to have lost its ability to effect social change. Their first project is more than a failure, resulting in a spell that unleashes a torrent of raw sewage and surrealistic embodiments of consumerist excess and black site torture techniques. Subsequent chapters feature an experimental composer (Koki?) and a performance artist (Panda?) whose bodies are literally invaded with the ills of capitalism, manifested through leaking blisters and other maladies, as well as a radical remix of a Raymond Carver story, questioning "What We Talk About When We Talk About Poetry."

The novel concludes with Panda and Koki returning to the site of their failed collaboration to conjure up a more utopian vision of "an army of lovers." Fantastical, lyrical, whimsical and wildly experimental, An Army of Lovers is as serious as it is absurd.

"An Army of Lovers explores the liminal spaces where cities and individuals come together and stand apart with strange, brainy grace."—Michelle Tea

"Two of my favorite poets, each with a unique voice, wangle a 'third mind' as they come together in a novel radically different than any I know. Like the 70s Rosa von Praunheim documentary on the 2nd wave gay rights movement (Army of Lovers or The Revolt of the Perverts), the newly minted Army of Lovers takes a stage crowded with multiple images, intent on creating a moment of revolutionary stillness inside the noise. Authors Spahr and Buuck, who appear in this novel as Bay Area poets 'Koki' and 'Demented Panda,' style it up all the way from magical realism to 'new journalism' and Raymond Carver Cathedralspeak, but it's the weary 'I can't go on. I'll go on' optimism at which wounded veterans of the army of lovers excel. Theirs is a rigorous book, and a book of marvels, with something funny, something painful, stirring on every page."—Kevin Killian

"Too often in the poetry world, self-awareness means dreary, self-important self-absorption. Thank goodness that is not the case here. This picaresque story about the 'particular lostness' of poetry, the ways poems always win and the lives of self-described 'mediocre' poets is actually pretty hilarious! It's also smart, incisive and politically astute. Now, to the barricades!" —Rebecca Brown

This avant-garde debut novel from poets Spahr and Buuck eschews convention while containing flashes of surprising humor and insight. The novel opens and concludes with the story of Demented Panda and Koki, two mediocre San Francisco Bay Area poets who decide to collaborate. Their planned epic poem is about a vacant lot on the border of two cities, but after a summer of talking, Demented Panda has written nothing, and Koki has produced so much that it&'s the same as nothing. Subsequent sections tell the story of a composer infected with a mysterious illness, and a reworking of a Raymond Carver story is offered. The links between these sections are tenuous, although descriptions of illness and observations of the roles of art in society create a thematic unity. The deprecations of the poets&' processes in the Demented Panda and Koki sections are funny, and the observations about art in the other sections are sobering. However, many readers will question the point of the disjointed narrative, and several sequences describing the manifestations of the mystery illnesses are hard to take. This experimental work is not for the faint of heart, but it is laced with meditations that will appeal to readers concerned with poetry&'s role in the world. - Publishers Weekly

Daniel Morris provides an extensive review of An Army of Lovers by David Buuck and Juliana Spahr in the Winter/Spring 2015 Issue of Notre Dame Review. " Spahr and Buuck express(ing) hope after hopelessness about the potential to reimagine poetry as a progressive social genres." "Unquestionably, Spahr and Buuck continue in An Army of Lovers to advocate for a collaborative textual engagement that pushes readers in the direction of building communities and participatory culture . . . poetry in An Army of Lovers does indeed make stuff happen" -- Daniel Morris

"By means of a series of stylistically and tonally various prose segments (by turns reflexive and dialogic, ironic and depressive, unhinged and hallucinatory, wetly emotional and dryly wry, including a detournement of a Raymond Carver story), the book centers, emotionally, on the ebb and flow of what it calls 'struggle-force.' Signature drone strikes, torture, ecological collapse, environmental illness and chronic fatigue syndrome: it's all connected." --Miranda Mellis

New York City might be home to the big houses, but this scrappy city just happens to be the epicenter of publishing on the Best Coast. Join Alexis Coe for Read Local, a series on books produced in the Bay Area. This month's installment guest-written by Evan Karp.

"The San Francisco Bay Area can boast of having both many great poets and many mediocre poets." Thus begins the unusual collaboration between poets Juliana Spahr and David Buuck, An Army of Lovers, which vaguely resembles both a novel and a lyrical meditation on the nature of art and civic responsibility.

There are so many factions of creative writing here that it sometimes seems each poet is a different form of poetics. Thus when any two people say "the Bay Area literary scene" they are almost definitely talking about two different things. Spahr and Buuck, who both teach at Mills College and are each respectively accomplished (if not adored) experimental artists, are as qualified as anyone to discuss what distinguishes a "great poet" from a "mediocre poet" -- should that ever be their goal.

The book's first sentence is quite misleading, though, as it may contain Army's only dichotomy; often reading like a lyric poem, much of the book is a sprawling and all-inclusive list of overlapping realities, refusing to call any one thing "as it is." For example, an artist is trying to make "a sound piece using found materials, a piece that might take all that she could know and feel about a military prison in another country and the bodies inside it, their movements and actions and sounds, and then somehow shape this into music, or protest, or she did not know what":

She wasn't sure what she wanted this new composition to sound like, what she wanted it to do. But she knew what she didn't want. She didn't want it to be easy to dance to or to be something to march to or to simply be parsed out in recognizable phrygian or lydian or dorian or locrian or aeloian modes. She didn't want it to reference endangered birds or privatized drops of water or other things that just made you feel sad. She didn't want it to be spare and lyrical or melodic and rich. She wanted it to be not easy to listen to but also not so hard to listen to that you'd just want to shut it off or want to just read the liner notes and nod your head to the implications therein, nodding as if to a beat, thinking the right proper political thoughts in the head but not also the messy ugly things that stir in the belly or resonate in the inner cavities of a right proper North American body faced with the implications.

The artist in question is the subject of the second of five vignettes, who suffers an incurably infected tick bite that begins to take on a life of its own. She tries to channel her fever into the creation of art, ignoring the growth as long as possible and finally giving in to it -- trying to give language to it, to let it speak for itself. As her doctor says:

I cannot cure you. No one can cure you. I can modulate your fever, but what is there inside you will still come; it's growing inside you, it's the you that's not you that's coming. And you can let it suck the life out of you or you can find in it fuel for action.

The book offers many ways of approaching the age-old questions What makes something art and What makes someone a decent citizen, as well as (if not primarily) exploring the ways in which the answers to these questions might intersect. More impressively, it does so without being didactic and yet without being obscure, as so many efforts at high-concept art tend to be.

Honestly, I just want to barrage you with big block quotes from passages selected at random (you can read a long climactic passage here). The book is so pleasant to read it's almost easy to forget the import of its queries, despite the fact that you may find yourself dogearing half of its pages. The result is what any good book should hope for: it leaves the reader with a feeling of wanting to engage, to become more involved, however that might be possible. The energy and honesty with which Spahr and Buuck have asked themselves the above questions permeate every page of this book, and are every bit as infectious as the pustule in section two.

Despite its charm and, well... poetry, An Army of Lovers is a dangerous book. To those creating, or interested in creating, it is an artful challenge -- one that includes in its confrontation a confronting of the confronters, which can therefore only be well-met. The finale is anthemic, the kind of swollen sense of pluralized subjectivity that was so manifest during Occupy and emerges, from time to time, when so properly summoned. Lawrence Ferlinghetti once said of Ginsberg's poem "Howl" that "the world had been waiting for this poem, for this apocalyptic message to be articulated. It was in the air, waiting to be captured in speech." The statement suggests maybe someone else would have eventually uttered the "message," though it also implies a world in which it never gets stated. The characters in An Army of Lovers might forever fluctuate between the belief that poetry is everything and the belief that poetry is not enough, and perhaps nothing, but they are forever trying to utter something of meaning -- hopelessly, even, at times, blindly; they may be unable to imagine a world that cares, but that won't stop them from trying to create a world that cares.

With so many in the Bay Area approaching these questions from different vantages, and with various degrees of education and commitment, An Army of Lovers represents the strivings of a sample population that arguably does not exist anywhere else. In scope, it includes all artists trying to transcend a capitalist society, to create poetry at a time when poetry does not seem to have much large-scale significance. But it's in the air here, and the authors have done a singular job capturing what might serve as a clarion call for anyone seeking radical transformation.

You can read the authors discuss the book in brief here and here, and even listen to them reading from the book. If you do the above and absolutely have to read the book but can't afford to purchase a copy, go on in to City Lights and read the whole thing; no one will stop you. - Evan Karp

I am fascinated by their attention to inequality, to questions of violence and community: something borne out by the collaboration itself."--Bhanu Kapil

"Authors who co-write often produce two halves that refuse to coalesce, but East Bay poets Juliana Spahr and David Buuck fuse with fantastic results in this short experimental novel. It's the story of Demented Panda and Koki, two poets united by a desire to write politically engaged works. Wounded, bored, inspired and skeptical, they soldier on through a landscape of toxic spills, consumer excess, odd juxtapositions and trance states."--Georgia Rowe

David Buuck, The Shunt, Palm Press, 2009.

Stuttering, hemming, hawing, failing, flailing, and flopping, the comedian tries to coerce the narrative ideology of wartime into a punch line, but the punch is always awready pre-packed by Big Brother's Big Other. As Beckett almost observed, nothing is funnier (or sadder, depending on your tolerance for correct allegorical apprehension of permanent crisis) than someone trying repeatedly to slip on a flipping banana peel and getting shut down every time. The Shunt puts the "tic Alpo" back in "political poetry."

The Shunt provocatively explores one of our most ordinary experiences of social discomfort—embarrassment for the flailing comedian and his all too visible affective labor—in a strikingly intelligent and utterly heartbreaking way. For all its acerbic tonality, The Shunt’s affective agenda is thus the exact opposite of ironic cynicism, which is one of this brilliantly discomforting book’s most delightful surprises.— Sianne Ngai

With its stutters, fractures, puns, sarcasms, and ironies, The Shunt is part of a cluster of books recently written by US poets attempting to understand what it means to live in a country that is constantly bombing other countries. But with its relentless attention to the group psychosis that this state of siege induces in US citizens, The Shunt is also something sui generis. This is your brain on war.— Juliana Spahr

Stuttering, hemming, hawing, failing, flailing, and flopping, the comedian tries to coerce the narrative ideology of wartime into a punch line, but the punch is always awready pre-packed by Big Brother’s Big Other. As Beckett almost observed, nothing is funnier (or sadder, depending on your tolerance for correct allegorical apprehension of permanent crisis) than someone trying repeatedly to slip on a flipping banana peel and getting shut down every time. The Shunt puts the “tic Alpo” back in “political poetry.” — K. Silem Mohammad

David Buuck’s first full-length collection, The Shunt, consists of work written between January 2001 and October 2008. It engages with the sense of urgency characteristic of this decade, the sense of constant, constantly mutating crisis that has dominated public perception of finance, politics, and personal life. In general, we have been in danger in this decade—whether the danger has been losing our jobs, losing our savings, dying of anthrax, losing our benefits, losing our homes, dying from suitcase nukes, dying because our health-insurance providers won’t pay for treatments, or losing our self-esteem or moral certainty because we can find no effective way to act on our deeply-held beliefs. Buuck, as I understand his work, views this atmosphere of crisis as a put-on, a con-job more coercive than force.

His book dramatizes the absurdity of the sense of crisis, using word-play and surprising substitutions to point to the tactics of media manipulation that keep the crisis from getting stale. Buuck suffers from the anxiety, just like the rest of us, but nonetheless demonstrates how hokey and old the crisis is, how the crisis refuses to grow up but just keeps sputtering out the same tired threats on everything we need and love. When Buuck writes, “here comes / the crash /again” or “(repeat for thirty days / (repeat for twelve years / (repeat” the reader can feel and share his weariness with living in interesting times, the intensity of his desire to get past the cycles of trauma and fear and move on to a mature politics.

Ultimately, the sense of crisis is fueled by the financial objectives of corporate elites, who insist upon an unsustainably high rate of profit for executives and investors. Much of The Shunt critiques the effect of these financial objectives on everyday life. Of the California economy in 2001, Buuck writes:

the 3 largest locals –

ag, tech, & prisons –

immigrant-dependent

(H-1Bs the new

Treaty of Guadeloupe)

“highly-mobile” – uh, that’s people?

Rx 3482960 household debt ratio

dwelling without foundation

to disposable incomes, subprimed

real estate flexes proof

is in the putting it that way. . .

Imagine

temporary workers

aligned by other than shared ironic

detachment from the dayjob

Here Buuck coordinates the aspects of the crisis into a grim picture of socioeconomics in 21st century California. As a demand for excessive profit simultaneously drives up the price of real estate, through speculation, and drives down worker compensation (through the definition of more and more workers as “temporary”), the only place for the economy to go is a vast expansion in working class debt. In this shift, the productive power of the working class is characterized as debt rather than ownership (leading ultimately to the view of debt as a form of ownership, of the mortgage as an asset). This helps us to understand how the crisis can at the same time have been a boom; it is because, as Buuck writes, “the debacle never comes. / belated, bet-hedged into after- / futures.” And even now that the debacle has come, now that we have been forcibly reminded of the distinction between ownership and debt, the crisis still fails to fully materialize, still situates itself primarily in “after-futures” of anxiety. ag, tech, & prisons –

immigrant-dependent

(H-1Bs the new

Treaty of Guadeloupe)

“highly-mobile” – uh, that’s people?

Rx 3482960 household debt ratio

dwelling without foundation

to disposable incomes, subprimed

real estate flexes proof

is in the putting it that way. . .

Imagine

temporary workers

aligned by other than shared ironic

detachment from the dayjob

Writing in 2008, Buuck further explores how the crisis is permanently tied to future-projections:

off in the distance, “tomorrow”

’s a video-game, a simulcast,

a set of shadow-icons

pegged to the budget-chart

“reality – plus

the future within it”

In other words, because present day economic activity in our highly-leveraged society is dependent on forecasts, predictions, and projections, the crisis will always be palpable and pending; the crisis is the public discourse that keeps our economic system stable by guaranteeing collective compliance. Because of the looming crisis, we have no choice. The form of our society, at least in the decade of the 00s, is that we are constantly experiencing the leading edge of a great crisis the bulk of which remains (permanently) ahead of us. In this environment, we can all safely say, “I trust my instincts – once / they’ve been medicated.” ’s a video-game, a simulcast,

a set of shadow-icons

pegged to the budget-chart

“reality – plus

the future within it”

Of course, “the crisis is an accountant / ’s wet dream” as the sense of impending crash motivates rapid price fluctuations in futures markets. Buuck writes:

it’s 12.99

it’s 18.99

it’s 29.99

it’s 36.99 & tonight

we’re gonna parlay

like it’s 19.99 – per

The remarkable use of the word “parley,” which refers both to speech and negotiation in general, and to a specific type of wager, is characteristic of Buuck’s close attention to terminology. A parlay is a bet in which two or more bets are linked together—a parlay is only won if all of the included bets are won, and if you win a parley you win big. The sense of crisis enables radical increases of value for speculative investors—wins which have the effect of deepening the underlying problem and making the crisis worse. In a speculative economy driven by the production of debt, there is never a final bet, so all the wagers won along the way remain permanently in question, all the profits ride on a future which can only culminate in crash. Because the crash is permanently pending, never to fully materialize, the short-term profits can be immense, but cannot lead to a sense of prosperity. Indeed, the unsustainable scenario of wealth without prosperity leads to zero-sum thinking in which wealth is only made of prospective loss. In this situation, infrastructure disappears because it has less profit potential than debt; wealth is a passing wave which will break on the (receding) shore of the crisis. . . it’s 18.99

it’s 29.99

it’s 36.99 & tonight

we’re gonna parlay

like it’s 19.99 – per

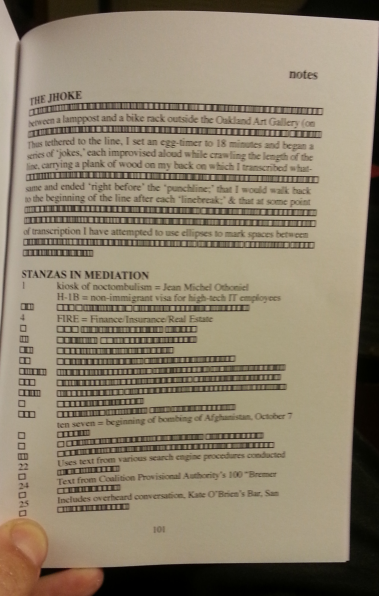

In such an environment, immediate physical reality and sensory experience are essential—as temporary as wealth but much more accessible. The Shunt studies language as a physical, sensory reality, concerning itself with the stutters and substitutions that characterize language in real-time. This concern is most effectively dramatized in the book’s first section, “The Jhoke,” described in the notes as follows:

I tied a length of rope between a lamppost and a bike rack. . . stringing the rope through and around my belt. Thus tethered to the line, I set an egg-timer to 18 minutes and began a series of ‘jokes,’ each improvised aloud while crawling the length of the line, carrying a plank of wood on my back on which I transcribed whatever I was saying/reading.

The resulting “jhokes” give a sense of language as stolen from the tension of the moment. The second “jhoke” reads in its entirety as follows:

A man … walks … into a … bar … room de … bate … over … the role … of … the writer … in war dash … time … I … ’d been … making … the … argument … that … the … eh … body dash … burden of … one’s experience … of war … dash time … need be art … art … articulated … as … ex … per … iential … lized … scripts … for … dot dot dot … how do you … spell ellipsis? … dot dot . . . the bartender … izer pours … me … a … grin and … bear it … and says …

In this text, the many pauses represent the insertion of the body into discourse. The body’s labor and the pause as the body prepares to utter speech are made visibly present by the ellipses, dramatizing how the body takes up time, how the body delays the progress of philosophical or financial discourses. Indeed, Buuck may be suggesting that it is the body itself, its solidity, that prevents the crisis of our times from ever fully materializing, the body that holds everything together by insuring a place for the present tense. Against financial and philosophical regimes that dominate us by manipulating future expectations, the body slows down and gets real. Consider the joke without the pauses; it would be “A man walks into a barroom debate over the role of the writer in war-time. I’d been making the argument that the body-burden of one’s experience of war-time need be articulated as experientialized scripts for … The bartenderizer pours me a grin and bear it and says”. In this version, intriguing yet facile art-speech is interrupted by the bartender’s good humor, triggering a pair of tenderizing puns. But in the version with the pauses, the contingent nature of each syllable as a physical manifestation is foregrounded as a series of present tenses in which “art” is gradually, stutteringly “articulated” at a rate of one “ex” per each “iential.” In this version, there is a yawning gap before the experiential goes on to be “lized” and the lie in experientialized is exposed as a dangerous afterthought.

Much of David Buuck’s writing develops out of or feeds into performative settings, including lectures, guided tours, dramatic enactments, and constraint-based performances like “The Jhoke.” This engagement with performance suggests uneasiness with the ritual of the “poetry reading”—rather than going from place to place reading the same poems in the same way, Buuck crafts performances of his writing that engage specifically with the location and social context. His work with the Bay Area Research Group in Enviro-aesthetics (BARGE) emphasizes an attentiveness to local environments of the San Francisco Bay area. This has included guided tours of the toxic Treasure Island site, as well as examinations of the gradual change in urban locations.

As in The Shunt, Buuck’s performances employ acts of attention as a form of cultural resistance. For Buuck, the material conditions of our embodiment and surroundings can act as a buffer, a space to slow down and call into question the narratives of crisis and transformation that shape our lives.

The Shunt cannot free us from the tensions of a decade of constant crisis, but it can offer us the body as a guarantor of real-time. By pointing out how the crisis is not new but rather a constant aspect of our lives, Buuck tries to show us how stale it is, and thereby to liberate us from being “shame-shaped into over- // choreographed pantomimes / of pre-apocalyptic glee.”

Rather than being excited or activated by the crisis, we can “grin and … bear it” at the slower pace of embodiment and attention. Of course, this is no cure. We are still “inside paren-ethical framejobs” where “the news / scams me into / codependency.” Nonetheless, The Shunt finds something that poetry can give us in this moment—the moment itself, on furlough from the dominated future. These acts of attention set an alternative pace, pointing away from crisis thinking and toward a more gradual and curious experience of our time. - Stan Apps

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.