Alfredo Bryce Echenique, A World for Julius: A Novel, University of Wisconsin Press, 2004.

read it at Google Books

Julius was born in a mansion on Salaverry Avenue, directly across from the old San Felipe Hippodrome. Life-size Disney characters and cowboy movie heroes romp across the walls of his nursery. Out in the carriage house, his great-grandfather’s ornate, moldering carriage takes him on imaginary adventures. But Julius’s father is dead, and his beautiful young mother passes through her children’s lives like an ephemeral shooting star. Despite the soft shelter of family and money, hard realities overshadow Julius’s expanding world, just as the rugged Andes loom over his home in Lima.

This lyrical, richly textured novel, first published in 1970 as Un mundo para Julius, opens new territory in Latin American literature with its focus on the social elite of Peru. In this postmodern novel Bryce Echenique incisively charts the decline of an influential, centuries-old aristocratic family faced with the invasion of foreign capital in the 1950s.

Winner of the Outstanding Translation Award of the American Literary Translators Association and the Columbia University Translation Center Award.

Up next in the Month of a Thousand Forests series is Alfredo Bryce Echenique, whose entry in A Thousand Forests includes a bit from his novel A World for Julius and a previously untranslated story, “Manzanas.”

One of the most intriguing things about Echenique’s life is the plagiarism case that he was involved in. Here’s a bit from Valerie’s intro that makes me think there’s a lot more to this story:

In 2007, Alfredo Bryce was embroiled in a bizarre accusation of multiple plagarisms. The episode, itself with the coloring of a spy novel, carried with it a certain enmity, but also the unconditional support of those who, like Enrique Vila-Matas and Mario Vargas Llosa, have been uncompromising in defending their faith in the writer, who continues to steer his literary course between suffering and laughter.And remember, you can only get Echenique’s previously untranslated story by purchasing this collection. And if you buy it before the end of the month, use the code FORESTS and it’ll only be $15.

Above all I like the pages I picked from Un mundo para Julius for their efficiency. Let’s not forget that they’re the first pages in the book and, in a condensed way, although not lacking in subtleties, they contain a lot of information about the novel’s central characters, with the exception of Juan Lucas—Julius’s stepfather and the novel’s antagonist—whose presence is implied in the nocturnal outings of Susan, Julius’s frivolous, widowed mother. But in addition to introducing the book’s main characters, these pages also introduce the book’s principal settings. The boy’s house is a microcosm of Peru, with borders that he crosses for the first time when he goes from the elegant part of the large mansion where he lives into the so-called “servants’ quarters,” an accurate reflection of a whole country that is profoundly and cruelly divided between the very rich and the very poor, and into distinct regions such as the coast, the world of the Andes, and the Amazon. From these immense and varied regions of Peru come the so-called servants of this wealthy family who, instead of taking interest in their own country, live with their eyes fixed principally on Europe and secondarily on the United States. And so Julius and his siblings attend British and American schools, where the few Peruvian teachers working there come off as deeply pretentious in the eyes of their students.

“Manzanas” is the long monologue of a young and beautiful nymphomaniac who competes with any good-looking girl who crosses her path, and who, at the same time, maintains a romantic relationship with an important musician who is much older, and is able to see her in a good light, even to overlook her infidelities. The tension comes from her admiration for the refined, cultured, and respectable man combined with her desire to surpass him in some way, petty as it may be. She doesn’t say any of this. She just suggests it. A murder, although only symbolic, might be the only way for the guilt-ridden girl to escape from her constant and spiteful obsessions and contradictions.

Julius was born in a mansion on Salaverry Avenue, directly across from the old San Felipe Hippodrome. The mansion had carriage houses, gardens, a swimming pool, and a small orchard into which two-year-old Julius would wander and then be found later, his back turned, perhaps bending over a flower. The mansion had servants’ quarters that were like a blemish on the most beautiful face. There was even a carriage that your great-grandfather used, Julius, when he was President of the Republic, be careful, don’t touch! it’s covered with cobwebs, and turning away from his mother, who was lovely, Julius tried to reach the door handle. The carriage and the servants’ quarters always held a strange fascination for Julius, that fascination of “don’t touch, honey, don’t go around there, darling.” By then his father had already died.

Julius was a year and a half old at the time. For some months he just walked about the mansion, wandering off by himself whenever possible.Secretly he would head for the servants’ quarters of the mansion that, as we’ve said, were like a blemish on a most beautiful face, a pity, really, but he still did not dare to go there. What is certain is that when his father was dying of cancer, everything in Versailles revolved around the dying man’s bedroom: only his children were not supposed to see him. Julius was an exception because he was too young to comprehend fear but young enough to appear just when least expected, wearing silk pajamas, turning his back to the drowsy nurse and watching his father die, that is, he watched how an elegant, rich, handsome man dies. And Julius has never forgotten that night—three o’clock in the morning, a lit candle in offering to Santa Rosa, the nurse knitting to ward off sleep—when his father opened an eye and said to him poor thing, and by the time the nurse ran out to call for his mother, who was lovely and cried every night in an adjoining bedroom—if anything, to get a bit of rest—it was all over.

Daddy died when the last of Julius’ siblings, who were always asking when he would return from his trip, stopped asking; when Mommy stopped crying and went out one night; when the visitors, who had entered quietly and walked straight to the darkest room of the mansion (the architect had thought of everything), stopped coming; when the servants recovered their normal tone of voice; and when someone turned on the radio one day, Daddy had died.

No one could keep Julius from practically living in the carriage that had belonged to his great-grandfather/president. He would spend the entire day in it, sitting on the worn blue velvet, once gold-trimmed seats, shooting at the butlers and maids who always tumbled down dead by the carriage, soiling their smocks that the Señora had ordered them to buy in pairs so that they would not appear worn when they fell dead each time Julius took to riddling them with bullets from the carriage. No one prevented him from spending all day long in the carriage, but when it would get dark at about six o’clock, a young maid would come looking for him, one that his mother, who was lovely, called the beautiful Chola, probably a descendant of some noble Indian, an Inca for all we know.

The Chola, who could well have been a descendant of an Inca, would lift Julius from the carriage, press him firmly against her probably marvelous breasts beneath her uniform, and not let go until they reached the bathroom in the mansion, the one that was reserved for the younger children and now belonged exclusively to Julius. Often the Chola stumbled over the butlers or the gardener who lay dead around the carriage so that Julius, Jesse James, or Gary Cooper, depending on the occasion, could depart happily for his bath.

And there in the bathroom, two years after his father’s death, his mother had begun to say good-bye. She always found him with his back to her, standing naked in front of the tub, pee pee exposed, but she never saw it, as he contemplated the rising tide in that enormous, porcelainlike, baby-blue tub, which was full of swans, geese, and ducks. His mother would call him darling, but he never turned around, so she would kiss him on the nape of his neck and leave very lovely, while the beautiful Chola assumed the most uncomfortable postures in order to stick her elbow in the water and test the temperature without falling in what could have been a swimming pool in Beverly Hills.

And about six-thirty every afternoon, the beautiful Chola took hold of Julius by his underarms, raised him up and eased him little by little into the water. Seeming to genuflect, the swans, geese, and ducks bobbed up and down happily in the warm, clean water. He took them by the neck and gently pushed them along and away from his body, while the beautiful Chola, armed with soapy washcloths and perfumed baby soap, began to scrub gently—ever so gently and lovingly—his chest, shoulders, back, arms, and legs. Julius looked up smiling at her, always asking the same questions, such as: “And where are you from?” and he listened attentively as she would tell him about Puquio, a village of mud houses near Nasca, on the way up to the mountains. She would tell him stories about the mayor or sometimes about medicine men, but she always laughed as if she no longer believed in those things; besides, it had been a long time since she had been up there. Julius looked at her attentively and waited for her to finish talking so he could ask another question, and another, and another. And it was like that every afternoon while his two brothers and one sister finished their homework downstairs and got ready for dinner. (Translated by Dick Gerdes)

- http://www.rochester.edu/College/translation/threepercent/index.php?id=12692

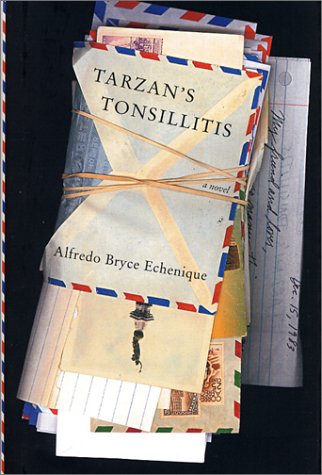

Alfredo Bryce Echenique, Tarzan's Tonsillitis: A Novel, Trans. by Alfred MacAdam, Pantheon, 2001.

From the internationally acclaimed Peruvian writer—winner of the Cervantes Prize, the most prestigious literary award in the Spanish-speaking world—a tragicomic story of improbable, inevitable love.

At the center: a couple in love, in exile together and apart. He is Juan Manuel Carpio, a second-generation Peruvian of Native American origins, a middle-class singer-composer. She is Fernanda María de la Trinidad del Monte Montes, a polyglot and cultured Salvadoran. Through the mostly epistolary narrative set in 1960s Paris, revolutionary El Salvador, Chile, 1980s California, and London, we follow the thirty-year arc of their relationship.

At once cheerful, hopeful, and informed by a serene lack of sentimentality, the narrative—rich with the delights of paradox and hyperbole—sees the couple through disastrous and traumatic marriages to other people; the ups and downs of their respective careers; the inexorable effects of politics on their personal lives; their shifting passions and gradual realization that the truest bond between lovers is a tender, abiding, and respectful friendship.

IN 1970, the Peruvian novelist Alfredo Bryce Echenique published a fictionalized portrait of his Lima childhood. Richly detailed and full of subtle scorn for his country's ruling class, ''A World for Julius'' is an exile's novel. It could only have been written in a seat of alienation like Paris, where the author lived and taught in the 1960's and 70's.

''Tarzan's Tonsillitis,'' Bryce Echenique's 14th published work, is something rather different -- an expatriate's novel, a rueful retrospective tribute to the heroic survivors of decades of rebellions and coups and dirty wars. The encomium takes the graceful form of a love story between a hyperarticulate Peruvian singer and composer, leading a charmed life in Europe, and the beautiful Salvadoran woman he worships from afar.

The star-crossed lovers meet in Paris in 1967, when Latin liberation movements and Latin ''boom'' novelists are all the rage. Fernanda María de la Trinidad del Monte Montes, a beautiful red-haired, green-eyed daughter of the oligarchy, arrives in town to occupy a sinecure at Unesco. She has an Alfa Romeo and great connections. Her exclusive Swiss finishing school has even taught her the correct posture to assume while hailing a taxi. Juan Manuel Carpio, the grandson of Quechua-speaking Indians, is at the beginning of his career, performing in the Métro with a Che Guevara poster as a backdrop to increase his tips. This unlikely couple fall in love, quarrel and separate, knowing right away that they have missed their great opportunity.

She goes off to Chile to study architecture and marries a photographer, who is forced to flee after being mistaken for a leftist by the Pinochet regime. They wander from Paris to Caracas to San Salvador, where it's Fernanda's turn to flee, this time after being mistaken for a right-wing sympathizer. In California, she toils bravely to support her abusive alcoholic husband and two children. The novel's only vivid character, she evolves from a Latina Holly Golightly into a woman of courage and stature. She's also the Tarzan of the cutesy title, her lover's pet name for her.

The tone throughout is resolutely cheerful and end-of-millennium mellow. Lines from so many famous tangos and boleros and ranchero ballads lace the text that it could be sold with an accompanying CD. To capture an era through its hit songs is a fine comic approach that has worked for other Latin novelists, but once he leaves the Paris of his youth, Bryce Echenique's writing turns disappointingly generic.

In fact, the trouble starts on Page 5, where Fernanda reports that she has been mugged in Oakland, Calif. In the original Spanish, she describes her attackers as ''terrifying gorillas (in size and color, I mean)'' and ''three huge, horrible black guys.'' These and other racial remarks are presumably meant as amusing signs of Fernanda's irrepressible Tarzan-of-the-jungle fighting spirit. Alfred MacAdam has the good grace to omit such slurs from his translation, but some of the novel's stereotypical assumptions are impossible to lose. If Oakland equals black street crime, Berkeley equals white male stolidity. Bryce Echenique's gringos are ''laconic'' when they're not ''monosyllabic.'' There's a pattern here: other men may compete for Fernanda's affections, but with Juan Manuel around no other male is allowed to get a word in edgewise.

Or is the author merely spoofing his own relentless volubility? The advantage of a long-distance love affair, after all, is that it's mostly verbal and imaginary -- like the work of writing a novel. -

Fernanda is the red-haired, green-eyed beauty Fernanda Maria de la Trinidad del Monte Montes, one of the angelic, Swiss boarding school-educated belles of an elite Salvadoran family. She is the partner of Juan's life, if not always his bed. He calls her a female version of Tarzan; brave, fearless, restlessly globe-trotting, her jungle yell sometimes loud, sometimes muted by circumstances.

Juan and Fernanda started as conventional lovers, but an older and wiser Juan, who narrates "Tarzan's Tonsillitis," admits that "when everything is said and done we were better by letter." They met in 1967 at a Parisian Christmas party for a glittery set of Latin American exiles; drawn by each other's sensitivity, they set up house together. But his self-consciousness and Fernanda's social status clashed; affection strained. Juan seemed obsessed with Luisa, the wife who left him, even though it was some idea of love that obsessed him, not the real woman (she's an ungrateful shrew). He and Fernanda drifted apart.

As the novel opens, the aging musician receives a letter from Fernanda, who's in Oakland, where her purse was stolen--the purse in which she carried all of his correspondence as if it were too precious to leave at home. That loss spurs Juan to recall the rich, bittersweet years that he's known her, spanning several countries from the 1960s to the '90s. He and Fernanda missed many chances to reunite as a couple, and yet, rather than ditch the whole thing, a special love grew that withstood everything. Their love is star-crossed, minus the tragedy that sent Romeo and Juliet to the cemetery.

"The blame for all this, as usual, rests with our 'Estimated Time of Arrival,'" Fernanda writes in one letter, using a travel metaphor to explain their fate, "which you and I obey with such discipline, and which always makes us arrive at different times, if not different places."

That's a nice poetic expression, but if two people are so deeply connected, why can't they get the timing right? One of Peru's best novelists ("A World for Julius") and short story writers, Echenique answers that question with more questions: Why must it work out? In the end, does love always lead to a platinum wedding band and a reservation for the honeymoon suite?

After that Parisian breakup, a couple of years passed and they met again. This time Fernanda was married and had a child; she was struggling to find work and her husband Enrique, an abusive drunk, was no help. Yet friendship arose among the three of them and Juan and Fernanda began to exchange letters, full of yearning and ideals, thus renewing a relationship that always worked best at a distance, when oceans separated them.

Why do this? Why would two educated people, whose conversations range from Hemingway to D.H. Lawrence to Dante, willingly agree to be divided lovers, continuously apart? Echenique subtly shows how their relationship evolved into a special form of consolation as each faced disappointments and sorrows.

Juan wandered far and wide, lonely, playing gigs while Fernanda returned to her violent Salvadoran homeland to find work. His letters comforted her and kept her sane in the madness of military executions and upheavals ("I love you and depend on you" she told him), and she consoled him, late in the novel, when his inability to love a psychologically fragile young woman had a tragic result. The reality of love really seems strange, less knowable after reading Echenique's novel. For some people, love is based on specific commitments; for Fernanda, it's something much simpler.

"At every turn in the road, and now in this damn mezzo of the road in the sometimes extremely dark forest," she wrote Juan, "the quality of your friendship has been a light."

Echenique skillfully captures the emotional changes as they travel that road. Because he's a Latin American, Echenique might get labeled with the overused term "magical realism" and, on the surface, that instinct initially seems right. Echenique's writing is magical. Only it's not the sort of magic that Gabriel Garcia Marquez and company are known for--beggars with angel wings, women who float into the clouds and disappear, circular narratives or paranoid dictators.

Echenique's magic is his graceful, stylistic way of touching his wand to a platitude about love and turning it to gold. When Juan and Fernanda meet again at the story's end, happy though not reunited like lovers in a typical happy ending story, Echenique convinces us of the cliche that true love, in some form, conquers after all, even if it doesn't result in a ride off into the sunset together. - NICK OWCHAR http://articles.latimes.com/2001/dec/27/news/lv-books27

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.