Wallace Markfield, Teitlebaum's Window, Dalkey Archive Press, 1999. [1970.]

Welcome to Brighton Beach of the 1930s and early '40s as filtered through Simon Sloan, from youth to would-be artist-as-a-young-man at Brooklyn College to the eve of his induction into the army. Wallace Markfield perfectly captures this Jewish neighborhood--its speech, its people, its unique zaniness.

But like any masterpiece--Joyce's "Dubliners" comes readily to mind--"Teitlebaum's Window "both survives and expands upon its time and place. While remaining rooted in the specifics of its own world, thirty-seven years after first being published it teems with Markfield's inventiveness, hilarity, and singular voice.

Framed in Teitlebaum's window, epochs pass in profligate and timely tributes to Teitlebaum's groceries (labor unrest = upward tilts in bagel prices) from 1932-42, while a decade (eight to eighteen) in the life of one Simon Sloan affords another manifestation of the times and verities of Brooklyn's Jews Without Money. In his first novel since the 1964 sleeper, To An Early Grave, Markfield tells his tale with high hilarity and a savage empathy from street spectaculars (fire-escape oratory, mock-Dos Passos time capsules) to domestic free-for-ails, mad bubbees and the gusty scatological interests of young males. Simon, the sometime searcher, later the aspiring writer, pursues sex and identity with a slow burn like the conflagrations at Luna Park. In diary notations early diversions are carefully recounted: Entertainment (""I listened to Jimmy Fiedler. He had on Charley Ruggles and Mary Boland""); Current Events via mother (""If you hear me say I'm upset France didn't fight a little harder it means the refrigerator came""); and School News (""Doris Reitzer vomited in school today. We had a CITYWIDE music teacher""). Brooklyn College offers fiery radical involvements, literary hopes and a certain Helene Grossberg but it's not really a meaningful distance from mother Malvena the Orphan and father Schmuel, Usher at the Lyric Theater. And Simon's tentative flowering threatens to droop on the stem, since Helene is weaving a marriage web which will probably position him as another artifact in Teitelbaum's neighborhood continuum. But there's good news tonight as war comes and Simon leaves with a hymn of thanks to ""Hirohito, Tojo and Mussolini."" Street scene by way of Allen's Alley and it's awake and singing all the way. - Kirkus Reviews

Wallace Markfield, To an Early Grave, Dalkey Archive Press, 2000. [1964.]

When Leslie Braverman passes away at the early age of 41, four of his closest friends are reunited on an odyssey through the streets of Brooklyn in a beat-up Volkswagen searching for the funeral parlor. In a series of fits, starts and wrong-turns, the comedic banter that suffuses the journey of these four Jewish proponents of New Criticism and little-magazine writing is quietly transformed into a quest for the intellectual, emotional and sentimental aura of the past.The basis for the 1968 movie "Bye Bye Braverman," "To An Early Grave" is a testament to the exuberant inventiveness of Wallace Markfield's writing.

"Wallace's 1964 comic novel follows the mishaps that befall four men cruising through the streets of Brooklyn, NY, on their way to bury their friend Leslie Braverman, who has passed away at 41. Though told with humorous overtones, the book reveals that what the men are truly mourning is the loss of the genuine sincerity of the past, which has been replaced by intellectual pretense." -- Library Journal

The line that spun me out of my chair in a fit of laughter came when the VW Beetle packed with New York Jewish intellectuals collides with the taxi. The furious cabbie menaces the VW driver. But one of passengers restrains the cabbie by muttering in his ear: “Don’t be a Shmohawk. He has an in with The Syndicate. He runs with the Trilling bunch.”

Even as Wallace Markfield’s dazzling debut, To An Early Grave, has largely faded from the literary landscape, that Trilling line – and many others – has remained with me lo these fifty years. Markfield’s slim novel was published early in 1964, won rave reviews, was filmed by Sidney Lumet four years later (as Bye Bye Braverman), and was reprinted several times (most recently by the Dalkey Archive Press in 2000). The novel also earned Markfield a Guggenheim Fellowship and a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. By all reckoning this writer should have had himself a solid and secure literary career (for what it’s worth, Markfield is the only contemporary writer saluted by name in Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint). But lasting fame was not to be for Wallace Markfield. His three subsequent novels showed a steady decline in artistry, critical reception and readership (one of those books would be privately printed). When he died in 2002 at the age of 75, Markfield was, if not quite forgotten, then indisputably overshadowed by such fellow Jewish writers as Roth, Joseph Heller, Saul Bellow, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Bernard Malamud, even Bruce Jay Friedman. His was a career that, we cannot refrain from saying, went to an early grave.

For all that, To An Early Grave remains not only a highly polished comic gem, but also something of a seminal work. This novel brilliantly captures a significant moment in American Jewish life and letters. That moment, which may be difficult for the current generation of readers and literati to appreciate, was a transitional stage when the sensibilities of bright and striving second-generation Jewish boys, chiefly from Brooklyn and the Bronx, not only dominated the nation’s intellectual journals but infiltrated and altered the wider culture as well. These fellows – and at the time this company was almost exclusively male – inherited the Talmudist’s talent for and dedication to textual scrutiny and interpretation. They applied these skills to the study of world literature, politics and history at institutions of higher education where the Jewish quotas were not in effect, such as Brooklyn College and the City College of New York. And then they expounded on such subjects in journals like the Partisan Review, The Paris Review, The Nation, The New Republic, Commentary, and numerous other weeklies and quarterlies with readerships of perhaps only a minyan or two.

They did something else in those journals, but we’ll get to that in a moment. Consider the task of reconciling, or if not reconciling then melding, two disparate cultures, one founded in Eastern European academies dedicated to the study of sacred texts, the other a product of the Enlightenment and focused on the aesthetics and psychological insights of western poetry and fiction. Think of Leslie Aaron Fiedler writing on Twain and Whitman. Think of Lionel Mordecai Trilling on Mathew Arnold and E.M. Forster. A similar cohort of clever Jewish young men took on history, politics, sociology, the arts. Indeed, their very names, sometimes bestowed by their parents but sometimes adopted by the bearers themselves, often as not signal the two cultures of these critical thinkers, these intellectual movers and shakers: Philip Rahv, Irving Howe, Alfred Kazin, Paul Goodman, Sidney Hook, Irving Kristol, Norman Podhoretz, Delmore Schwartz – we could add a dozen or two more names even before stretching to art critics like Clement Greenberg and Hilton Kramer and Harold Rosenberg.

The four occupants of that VW Beetle – the main characters in To An Early Grave – likewise all bear bicultural names – Barnet Weiner, Holly Levine, Felix Ottenstein and (somewhat puzzlingly) Morroe Reiff – and they are in that VW on the way to the funeral of one of their biculturally named colleagues, the 41-year-old Leslie Braverman. So too of course their creator bears a moniker that points to the two cultures. Like Wallace Markfield, who published his first article in the Partisan Review and whose literary heroes were Joyce and Celine, the four characters are all New York intellectuals. None of them, however, neither characters nor creator, is of the first generation of Jews making a splash in New York’s literary and political journals. This is not the Trilling or Rahv crowd of the 1930s and 1940s but their students and descendants. And functioning as they do in the late 1950s and early 1960s, they arrive at a particular moment and make their own peculiar contribution.

The moment was when art began to go pop – when artists like Lichtenstein, Warhol, Rauchsenberg, Oldenberg and many others made celebrated and inconic artifacts of American mass culture and consumerism, when American movies (movies, not “film” or “cinema”) became the subject of intense critical analysis, when other manifestations of popular taste and even kitsch were deemed worthy of intellectual scrutiny. Small wonder that Markfield’s characters – and many of their real-life counterparts – responded with alacrity to these developments. These sharp New York lads, bearing their bicultural names, grew up in somewhat insular Jewish households and were eager to embrace the wider culture. They became obsessive devotees of baseball, comic strips, movies, pulp magazines and other forms of mass entertainment. And when the opportunity arose, they began pontificating in their scholarly and literary journals not only on Oliver Twist and Karl Marx, but on Orphan Annie and the Marx Brothers.

Indeed, one of the great set pieces in To An Early Grave involves a cutting contest between two of the VW passengers. (What was the name of the Green Hornet’s driver?) Another involves movie trivia. (Name the horses of Tom Tyler, Bob Steele, George O’Brien, Hoot Gibson, Ken Maynard and Buck Jones.) Yet another concerns radio serials. (Who was The Shadow’s girlfriend?) Such popular culture references abound on virtually every page of the novel. (Markfield himself was a master of such trivia. For a time he wrote about movies for the New York Times, where he frequently flaunted his knowledge of Hollywood detritus.) It all sounds like amiable nonsense, until one recalls that by now the study of popular culture has become a mainstay at countless universities, with its own learned journals and societies (and leading to the observation that American higher education went down the tubes when it substituted the study of King Lear with the study of King Kong).

At the same time, To An Early Grave arrived at another auspicious moment – the debut of a new post-Borscht Belt brand of Jewish American humor, satiric, slashing, usually more educated and often more overtly Jewish than ever before. In the world of stand-up comedy it was exemplified by Woody Allen, Mike Nichols and Elaine May, Lenny Bruce, Shelly Berman and the unaccountably Canadian Mort Sahl. In literature it was foreshadowed by Philip Roth (Goodbye, Columbus in 1960) and Bruce Jay Friedman (Stern in 1962) and would hit its heights in the later 1960s (Portnoy’s Complaint, Heller’s Catch-22, and many others.) In this regard To An Early Grave is unabashedly Jewish. It customarily employs Yiddish words and phrases without bothering to translate them, and its characters adopt the speech patterns and even accents of their less assimilated parents. Markfield’s quartet may have fled Brooklyn and the Bronx for the greener pastures of Greenwich Village and the Upper West Side, but they do not deny their Jewishness. They may have shed the religious practices in which they were raised, but they have not adopted any others.

To An Early Grave, then, remains a fascinating literary curiosity, brimming with intellectual energy, crowded with pop cultural references and evoking as much laughter as any stand-up routine. It’s tightly written and economical in structure – four men on their way to a funeral (which some critics have compared to the funeral episode in Joyce’s Ulysses), but it’s packed with carefully crafted “bits,” as the comics might call them. Seven pages depict a literary critic struggling over the first sentence of an essay (“…yield pleasure of a kind… yield a kind of pleasure… but a pleasure increasingly tempered….”). This includes something that will cause not a few writers to wince:

Surely, essays such as these are bound to yield…

Then he went to the refrigerator and tightened all jars, twisted Handi-Wrap around half a tomato, two scallions, a tarnished wedge of Swiss Knight, and with moist toweling wiped a ketchup bottle and a butter dish.

Then he went to the stove and with a wire brush painted Easy-Off into the oven and put scouring powder, steel wool and dry paper toweling into the jets and burners.

Then he went to the garbage pail and lined the bottom with aluminum foil, and with Scotch tape fixed a plastic bag to the sides.

Then he went to the sink and stooped amid the pipes and set up a milk carton that it might be handy for coffee grounds and grease.

Then he went to the bookshelves and at the bottom of the vertically stacked Kenyon Reviews found the one Playboy and, though fighting not to, shook out and inspected from many angles the center fold.

Then he sat.

Then he took up his match again and peeled four more perfect strips.

Then he hummed, hummed and clapped hands to ‘The March of the Movies.’

And he hissed softly, ‘Trilling… Leavis… Ransom… Tate… Kazin… Chase…’ and saw them, the fathers, as though from vast amphitheater, smiling at him, and he smiled at them.

And he typed, with smoking intensity he typed:

“Of course, professor Gombitz’ essays, gathered together for the first time’”

We also get thumbnail sketches of a half-dozen walk-on mourners:

There was Maurice Salomon, the editor of Second Thoughts with his Robespierre profile. He had the air of the oldest of men, as if he had been through the Hundred Years’ War, taken down Sacco and Vanzetti’s last words and seen all movements turn into failure and fiasco. He would be twenty-nine, make it thirty, on his next birthday.

We witness a mourner at the graveside already pitching an article on the deceased to an editor:

“I see, then, not a piece that would definitely pigeonhole Leslie — though the, ah, cultural configurations have critical bearing – but a kind of retrospective reappraisal. In a way that all reappraisals are retrospective. ‘Leslie Braverman: the Comic Vision,’ or ‘The Comic Vision of Leslie Braverman.’” And we get that endless competition over pop culture expertise. (One character boasts: “My piece on John Ford has been twice anthologized. Twice!”

And in a paragraph that captures the love, the jealousies, the resentments, the profound and delicate brotherhood shared by all of his characters, Markfield tells us:

Even after Leroy’s last note went pining upward; even after the coffin was rough-handled by the four diggers; even after they had set it on that evil-looking contraption and jacked it up, and it hung and then slid into the pit; even after he flung his handful of dirt; and even after Ottenstein, Weiner and Levine bawled openly, Morroe held back. Shithead, he labeled himself, horse’s ass, peculiar creature. You could cry when the planes shot King King off the Empire State Building. You could cry when Wallace Beery Slapped Jackie Cooper and then punished his hand. You could cry when Lew Ayres reached for that butterfly.

But even so, nothing wet came from his eyes.

Despite its manic comedy, To An Early Grave ends on a sad and melancholy note, rather like Wallace Markfield’s career. After his brilliant debut, his next novel, Teitlebaum’s Window (1970), both puzzled and disappointed readers. Twice as long as To An Early Grave, an evocation of growing up Jewish in Brooklyn, is exquisitely detailed and often very funny. But it is also plotless, scattered and, perhaps assuming license by the example of Portnoy’s Complaint, which preceded it by a year, is scatological and crude in the extreme. Teitlebaum’s Window received a scabrous review in the New York Times Book Review by Alfred Kazin (also no fan of Portnoy’s Complaint). The book did win some praise but did not sell well – and there was no movie version or paperback reprint. Four years later came You Could Live If They Let You, a short and somewhat confused story of a Jewish stand-up comic that found few readers. Multiple Orgasms was privately printed in a signed edition of 350 (I own copy 148). In a 1978 interview, Markfield said he got bored with both You Could Live and with Orgasms, the latter so much so that he didn’t bother finishing it. Much later, in 1991, Markfield attempted to revive his career with the marked departure of Radical Surgery, a kind of satiric political thriller. This novel pretty much sank like the proverbial stone. Five years later, Markfield died.

“Don’t be a Shmohawk. He has an in with The Syndicate. He runs with the Trilling bunch.” Many today would not recognize that arcane “shmohawk” as a softening variant on the Yiddish schmuck. Many would likewise be puzzled by the reference to a “Syndicate.” Still others would be left blank-faced by the notion of a “Trilling bunch.” Maybe To An Early Grave is both a product of its time and, unlike the works of Roth and Bellow and others, is fatally fixed in it. So be it. I still find it a minor masterpiece. - Matt Nesvisky https://www.openlettersmonthly.com/fifty-years-to-an-early-grave-the-bittersweet-career-of-wallace-markfield/

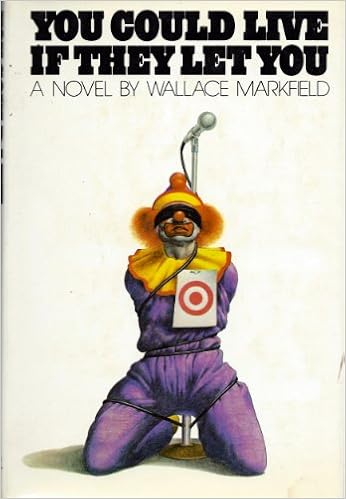

Wallace Markfield, You Could Live If They Let You, Alfred A. Knopf, 1974.

His third book, the story of a young comic trying to deal with the crazy people in his life.

Chandler Van Horton's posthumous bio of comedian Jules (Julie) Farber is really an excuse for the author of Teitlebaum's Window and To An Early Grave to string together a series of jokes and monologues whose hilarity and sometimes questionable taste should give Philip Roth and Jackie Mason, not to mention Don Rickles and Buddy Hackett, the old bird. ""You're an Italian kid, right? Am I right? I can tell -- you know how I can tell? Because you got no neck. . . . Give me your tired, your poor, your hungry masses yearning to breathe free -- and I'll make a fortune from costume jewelry. . . . In your country -- I bet in your country you don't see too many women like Mrs. Gandhi. Oh no sar. After all, she's not pregnant."" The wife of the Jewish President complaining about the lack of closet space in the White House. Postcards, phone calls, real and imagined conversations (diatribes) with soon-to-be-ex-wife goy Marlene and autistic son Mitch, with sister Lillian, and, of course, with love-hated WASP Chandler: ""I would tell you -- you know what I'd tell you? To kiss my ass and shit in your hat. Only by you people that's love-play."" There's not much more as the hysterical Julie approaches his heart attack con Jewish brio and Chandler learns maybe a little more about the folk who learned handwriting on the back of brown paper bags-- but that's more than sufficient for a continuously entertaining and often hilarious novel with a brilliant ear and eye for the wacky world of TV comedians who apotheosize, symbolize, and cauterize it. - Kirkus Reviews

Wallace Markfield's new novel confirms a suspicion I have long entertained that most of the explicitly ethnic Jewish novelists are really, by the nature and the limitations of their gifts, writers of short stories and satiric sketches. One painfully vivid illustration of this rule‐of‐thumb is the precipitous slide of Philip Roth's career from the modest peaks of short fiction in “Goodbye, Columbus” down through “Portnoy's Complaint” to the disasters of his most recent attempts at novel‐writing.

Wallace Markfield's three novels illustrate this rule in another way. A large part of his problem as a writer, like Roth's, is an addiction to mimickry. Not mimesis, the imitation of reality, but mimickry, the imitation of ethnic and social quirks, tics and mannerisms, often with a caricaturist's emphasis of exaggeration, a freedom of fantastic elaboration, that belong to the art of a stand‐up comedian. The chief impulse in all of Markfield's fiction is to “do” in this way an abundance of familiar types and scenes—the aggressive lady in the harlequin pants‐suit, the zealous Jewish housewife on a marketing expedition, the talkative Jewish cabby, the candy store of a remembered Brooklyn, the cafeteria at Erasmus Hall High School.

The trouble with all this, however well done it may be, is that as imitative performance of stereotypes it is essentially static, does not lend itself to the kind of psychological and thematic development, the kind of progressive revelation, that would justify the length of a novel. Such mimickry makes itself felt as dead weight at a number of junctures in “To an Early Grave,” Markfield's first book; in “Teitlebaum's Window,” his long second novel, it eventually turns the book into a crushing bore.

Now, “You Could Live If They Let You” seems to resolve this contradiction between the technique of the comic performer and the art of the novel by actually making its protagonist a stand‐up comedian. Jules Farber, the wry, paradoxical, sour‐edged, Yiddishslinging, hip‐talking comic, celebrated as a culture hero after his early death, is clearly modeled on Lenny Bruce, at least in regard to his mode of comedy. (Bruce is mentioned by the narrator as a predecessor to Farber.)

These quick thrusts punctuate longer, more fantastic set pieces on the Bruce pattern in which Farber needles the Lord of Hosts in show biz language, suggests that the Jews refused a deal to convert in Inquisitorial Spain because Torquemada wouldn't let them phone their mothers regularly, delivers a monologue as Tarzan's Cheetah, casting him in the role of a kvetching, Yiddish‐accented Equal Opportunity Employer.

The humor of Farber's character and performance, moreover, is set in a sharper perspective because the Jewish comic is presented to us by a superWASP narrator, a self‐conscious literary intellectual named Chandler Van Horton, who is constantly explaining Farber's Yiddishisms in high‐falutin Little Magazine English, solemnly matching the comedian's coarse ethnic witticisms with Nietzsche, Dostoevsky and Joyce. A happy narrative contrivance, Van Horton is a source of humor in himself, provides glosses on Farber's esoteric Jewish allusions for the uninitiated, and is a wonderful foil for the zany, troubled protagonist.

One should be duly grateful for these virtues of comic invention, but they do not succeed in making “You Could Live If’ They Let You” more than an assemblage of ingenious bits—not a novel but a book that might be called “The Best of Jules Farber,” the various performances of a deceased, non‐existent comic recorded at home and on stage. After the first 60 or so pages, we have had Jules Farber, heard all his principal routines; and, with no’ imagined depth as a character, he is little more than the aggregate of his routines. Since Markfield has no real plot or larger ordering conception of his materials, he can only repeat the routines with variations until they grow tedious and the novel winds down into pointlessness.

At the very end, Farber intimates that reality itself may have become a hopeless mishmash of vulgar inanities; he prophesies that (like the subjects of his own comedy), “Everything will be trivia and everything will be nostalgia.” That apocalypse of kitsch has fortunately not yet arrived, but Markfield writes as though it were fully upon us, excluding all possibility of coherent narrative design, limiting fiction to a mocking imitation of trivia, an ambiguously ironic exploitation of nostalgic recall.

- There are maybe one or two novels funnier than You Could Live if they Let you. Catch-22 and A Confederacy of Dunces come to mind. Imagine Lenny Bruce crossed with Mark Twain. That's Wallace Markfield. And no, the Jews did not kill Christ. But they did lean on him a little. - Chris Orlet @ amazon.com

Wallace Markfield, Multiple Orgasms, 1977.

Wallace Markfield, Radical Surgery, Bantam, 1991.

Concerned that the new Soviet leader's popularity will threaten the United States' permanent war economy, the U.S. President finds his fears dissolved by a series of shocking assassinations of prominent Americans

A dark satire, this depicts the chaos that develops after a Russian political reformer and his message "Peace, Sympathy, Brotherhood and Purest Joy" cause a mass transformation in the Soviet psyche. His influence is mistrusted and feared at the highest U.S. levels, lest it spawn an unwelcome easing of international tension or domestic social flux. Horrendous "dirty trick" bombings and killings by phony devotees of the benign Russian are staged to whip up hatred and anger and discredit the growing movement. A weak U.S. president lost in his thoughts and obsessed with his declining popularity allows the carnage and trickery. Various half-baked and absurd characters add to the mix of ideas, issues, and cynicism that, along with the enigmatic plot, will provoke thought, shock, and some amusement. Briskly told, this novel by a satirist whose books appeared in the 1960s and 1970s is troubling, antic, and absorbing. Recommended. - William A. Donovan

Markfield's ( To an Early Grave ) satire of de-Stalinization presents a charismatic Pavel Gavrych, risen to power in the U.S.S.R. and reaching out to the U.S. in amity in 1993. As a new American president agonizes about dismantling 50 years of a wartime economy, his powerful aide Harry Porlock devises a scheme to have the terminally ill commit heinous terrorist acts ostensibly directed by Gavrych. The book ends with a new red scare in the U.S. and a re-Stalinization of Russia. Among other inanities, the hyperbolic political takeoff features the nameless president's internal dialogues with JFK, who sports a stage-Irish brogue; a first lady as a sex-crazed twit; a precocious nymphet as part of the president's inner circle. With the president's understanding of American as "the hoi, the polloi, the louts and lumps, eating and drinking their fill at some great American trough and moving in multitudes from sea to shining sea," this tale falls somewhere between Joseph Heller and Richard Condon. Mostly it just falls. - Publishers Weekly

Satirist and magazine writer Markfield, whose You Could Live If They Let You (1974) put a Jewish president and a lot of one- liners into the White House, puts a syntax thrasher in the same spot and an absurdist in the Kremlin. Situation outweighs plot in this densely written, relentlessly sardonic sendup of presidents and geopolitics. The situation is the ascension to Soviet power of Pavel Gavrych, whose pure and burning teenage devotion to Marxism/Leninism as practiced in the Workers' Paradise came face to face with the cruelty of Uncle Joe Stalin in a personal meeting in which the generalissimo dislocated the lad's thumbs to show him the way of the world. Forty years later Gavrych turns Soviet communism on its ear by unleashing the most bizarre inherent forces of central planning and authority. The upshot is a totally confused state no longer inimical to the West--as a result of which America's gabbling, dreamy President panics, seeing no role for himself in a - Kirkus Reviews

Speaking of Wallace Markfield (1926-2002)—the Joyce of Brighton Beach, the great magician of old Brooklyn rhythms—it’s impossible to avoid mentioning that he was Jewish, for Markfield’s books are Jewish to the core: the DNA of every sentence shaped by the inflections of the New York State Diaspora (and a purer strain than that popularized by Woody Allen, once upon a time). The form of his work is itself a result of, and a tribute to, the convolutions of the English language, tortured into beautiful bonsai shapes by the impositions of Yiddish syntax. (As my grandfather is fond of repeating, “You don’t know English till you’ve learned it from an immigrant.”)

But Markfield is no documentarian: his work may contain bits and pieces of what could be considered time-capsule material—Depression-era Brooklyn; the ’50s and ’60s in the Partisan Review-Commentary axis—but, as with the best literature, these are points of departure: the foundations on which another, more personal, and basically fantastic world is created, just as the language—itself already given to parody and hyperbole—is refined and stylized into a gorgeous pidgin of high modernism and low burlesque.

Where others give us measured and precise introspection, Markfield’s novels brim with excess. He gives no quarter for those of us without the Yiddishkeit—in the broadest sense—to keep up with his nonstop references (“Scratch a Litvak [a Lithuanian Jew] and you’re peeling radishes!” Cosa significa?), the stamina to wade through his wonderful lists, the knowledge of pop culture necessary to match his phenomenal mastery of movie trivia (“How I survive, I don’t know, but we’ll say I survive World War III. . . . Then through the vapor I’ll see him. . . . And we’ll walk to each other and we’ll touch and feel and pound on each other’s backs. . . . And he’ll go, ‘Cagney and Robinson played together in one picture and one picture only, and the name of that picture was . . .’ ”), about which Markfield would later mourn that “each chapter lost another ten thousand readers”—but who’d want to be spared even a word of his “splendid nonsense” if given the choice? (Let the “less is more” crowd bail out now.)

It breaks my heart to know that Markfield felt overshadowed by Saul Bellow all his working life—even claiming that he’d dream about Bellow after the publication of every new novel, and once that his own mother was ignoring him in favor of the Nobel laureate, who’d turned up at her house for a visit. So let me take my little life in my hands now and go on record to say that, much as I like Bellow—and I do like Bellow (as did Markfield himself: “I don’t think I especially care to compete with Humboldt’s Gift,” he sighed in an interview)—I’d read Markfield any day in preference. Paragraph for paragraph, page for page, Markfield had the chops. Or, to put it less antagonistically: Markfield was a Bellow for the “other tradition,” a Bellow for the adventurous, for the puzzle-lovers, for the collectors of bric-a-brac and debris: a Bellow who they never noticed, or else studiously ignored (probably because of all the comparisons to Bellow)—and a “Jewish-American novelist” somehow doomed to obscurity at the very moment the categorization was coined.

The rush to fill that vacuum, to profit from the sudden, post-Augie March “marketability” of Jewishness, both opened the door for Markfield’s novels, and then left their author far behind. The ascendancy of his peers (Malamud, Roth)—writers whose versions of this world were by comparison sanitized of “otherness,” packaged for an audience who at worst wanted a tourist’s taste of a charmingly irrelevant, adorably neurotic part of the culture—served to eclipse him completely.

Markfield’s first novel, To an Early Grave (1964), was praised by Joseph Heller, won him a Guggenheim Fellowship, and was adapted for the big screen as Bye Bye Braverman, directed by Sidney Lumet, a few years later. (DVD release, someone?) It’s the most staid, the most buttoned-down and minimal of his great novels, though his verbal precocity—the protean babble that would become manifest in his next book—is already simmering behind its seemingly naturalistic prose. Leslie Braverman, writer, schmuck, friend, philanderer, has passed away at the age of 41, shocking his somewhat dispersed and alienated group of compatriots (critics, professional speechwriters, academics: our protagonist is the redoubtable Morroe Rieff—played by George Segal in the Lumet—whose epithet of choice is “Whoosh!”), now reuniting to organize an expedition to his funeral.

This crew is a gallery of grotesques—lovable at forty years’ distance, but at the time bringing out a tremendous hostility towards Markfield, who in his very first book was taking brazen potshots at the same crowd who could have made him the “next big thing”: the same crowd he knew intimately, and the same crowd he ran with . . . until To an Early Grave put him in permanent exile.

Braverman is no angel himself, but two-bit as he may have been—wasting his life on potboilers and co-eds—his friends (now undergoing one Odyssean delay after another as they try to get out of Manhattan) are still mediocrities by comparison. Though dead from page one, Braverman is already the perfectly formed Markfield hero. Cheerfully amoral in life, he was such a perfect picture of solipsism that he could write the following to his wife, in a fit of goodwill, despite their separation on account of his many affairs:

Such is my state that I will remit all sins, even these:

That you have not read my work in three years.

That you do not utter little cries in sex.

That in company you will not laugh at the second hearing of my jokes.

And in one of his few “in-person” cameos, he confronts Morroe Rieff in a dream, walking out of King Solomon’s Mines in a second-run house off Times Square:

Hey, hey, what are you doing there? Morroe wanted to know.

Here? Here I’m the white hunter.

Am I mistaken or don’t you look shorter? How come you look so short?

How come? How come is I said schmuck to a witch doctor!

[Morroe] sprang from his seat to follow Leslie into the brush, but found himself in [John Ford’s] The Informer. After betraying Leslie he treated half of Dublin to egg creams.

When Morroe wakes up, however, it turns out he’s been slumped against the shoulder of one of his fellow mourners in the car:

“Your grandma should one night pine for you and decide to come down and pay a visit from heaven, and she should want to kiss you and you should drool and dribble on her the way you drooled and dribbled on me.”

“Eifelsleep,” Morroe said through his yawn.

But good as it is (and To an Early Grave’s subtle accumulation of weight, of sadness and loss—and this through a pretty much exclusive use of comedy—ought to be studied in every writing program in the land), it’s Teitlebaum’s Window (1970)—Markfield’s “big book,” his Portrait of the Artist and Ulysses all in one—that makes him a giant. Superficially, it’s about one Simon Sloan, coming of age in the 1930s: growing up, going to Brooklyn College, and marching happily off to war to escape both a prospective marriage and his violently off-kilter parents, Shmuel and Malvena the Orphan; but no one reading Teitlebaum for the first time could possibly mistake the book for a mere slice of Depression life. Its first chapter—which ideally I could quote in full—is one of the best, most astounding, harrowing, and hilarious openings of any novel in the English language. It’s the sort of performance you want to put your book down and applaud after reading.

It begins in earnest after a brief digest of recent life in Brighton Beach, a litany that seems to hark back to some nonexistent preface (the book begins, “Then in June, 1932 . . .”), and which gets repeated every few chapters with updated information presented in roughly the same order—what Teitlebaum the grocer writes on the window of his little shop, which celebrity Stanley the taxi driver is claiming to have picked up in his cab. Thus briefed, we’re thrown headlong into the hot and stuffy Sloan apartment, where Shmuel is, for the moment, asleep (he mutters things like “Pogrom” and “Piecework” through his “agonized snoring”), and little Simon is getting Malvena the Orphan to tell him the story of her early years again, being worked to the bone and generally exploited by Cousin Phillie out in Hartford, Connecticut.

She’s sitting in a man’s undershirt so as not to bind or chafe her “dropped stomach,” reading to him from her journals and scrapbooks, even though, as she says, her autobiography, The Truth of My Life, is still in the “drafty stage.” It’s an encyclopedia of petty complaint, with chapters like “Cousin Phillie: How He Tried to Hire Me Out to Schvartzers,” and all the while Simon sings snatches of songs, crawls around on her lap, and brazenly pokes her barely covered breasts through her shirt (“When they jiggle, you know what they look like Mommy? Heh? . . . Just just just like Betty Boop’s eyes!”). When Shmuel wakes up, we get his stories of being in basic training during World War I (“‘It’s worth teh-hen armies to hear how they talk. . . . Shee-yut!’ he cried. And as Simon and his mother whinnied and swelled with mirth he gave them a ‘Fah-hark you! . . . In my company alone I must have had—I had—ho-boy!—three, four kinds goyim’ ”), and a few rounds of his ongoing fight with his son, with whom, as he says, “I try and I try and still I don’t get close to him.”

Simon sobbed out the Pledge of Allegiance.

“Get killed for Jackie Cooper!” his father told him.

Simon, planting an elbow on the table, made believe his was doing Palmer penmanship, throwing in also the closing hours of the library and the number of books he was allowed on a children’s card.

“Get killed with Jackie Cooper.”

Simon recited the holiday prices at the Lyric [Theater], the day for the changing of bills at the Miramar and the Surf.

“Get killed by Jackie Cooper.”

I could keep going: there’s more happening in this first chapter than in any three novels—Jewish-American or otherwise—you’d care to mention. By the time chapter two comes around, we’ve been so completely immersed in Markfield’s world that he can cover vast narrative distances with only a bit of shorthand. The book wastes no time with the verities of realism—we get most of our information from here on in through Simon’s journals, and we learn exactly what kind of a filthy kid he is, firsthand. What he and his friends get up to might make modern parents thankful for the relative innocence of video games—but as the book progresses, there are hints that Simon might one day redeem himself, grow up to be the sort of person who could write a kind of Teitlebaum’s Window of his own . . . and, thankfully, hints are all we get. ***

Markfield’s timing is a thing of wonder—how he makes dead words on a page sizzle and hiss, how he makes us hear his dialogue: not as lines recited by imaginary people behind a little proscenium in our heads, but as meter, as rhythm, as set-up and punch line. Teitlebaum and To an Early Grave are nominally comedies, but they get at everything that literature is for: they renew the language, and in the process, quite by accident, they renew us readers as well.

So, an old story: a writer done in—to his mind—by the very idiosyncrasies that make his work unique, that make it sublime. Markfield was never meant to chisel out the kind of stolid prose that would have won him Bellow’s following—however finely crafted, however elegant, however insightful. His muse was pricklier, sillier, and more melodic than Bellow’s. Its precocity could barely be contained, and maybe was a little too Jewish for readers who could only take so much exotica in their diet. Of course, losing out to the likes of a Saul Bellow is nothing to be ashamed of—but Markfield even lost out to his lessers, and seeing them enshrined now on curriculums and chockablock in bookstores, I have to wonder: why is there no room for him?

Even the great Stanley Elkin—the closest stylistic analogue to Markfield, and a writer who used to joke that he knew all his readers by name—has enjoyed a greater popular and critical success; and even Elkin had no time for Markfield, because Markfield had a genius for alienating exactly the people who could do him the most good, or else were most likely to appreciate his work. I hope that the audience he was really writing for—whether he knew it or not—will find him now that the dust has cleared. And should you chance to run into him in Olam HaBah, here’s your “in”: the answer is Smart Money (1931). - Jeremy M. Davies www.dalkeyarchive.com/reading-wallace-markfields-to-an-early-grave-teitlebaums-window/

Had he lived, Wallace Markfield would have celebrated his 86th birthday this week. But it’s been 10 years since this word-slinging tummler left the stage, and you have to wonder if he didn’t write his own epitaph decades earlier. In the most famous line of his first and best-remembered novel, To an Early Grave—a book that treated New York Jewish intellectuals as though they were Catskill comedians—Markfield described its deceased prime mover as “a second-rate talent of the highest order.”

Put another way, Markfield was the most gifted also-ran associated with the so-called Jewish-American literary renaissance of 1950s and ’60s: His three Jew-obsessed comic novels were eclipsed by the titanic oeuvre of Philip Roth, his ideas regarding Jews and popular culture were massively elaborated by professor turned new journalist Albert Goldman, and his promising bid to establish himself as a wise-guy, street-smart luftmensh-intellectual Jewish film critic was upended by Manny Farber and trumped by Pauline Kael.

Markfield enjoyed maximum visibility between the 1964 triumph of To an Early Grave (the basis, four years later, for Sidney Lumet’s seminal Jew Wave movie Bye Bye Braverman) and the friendly, if more ambivalent, reception given his ambitious second novel, Teitelbaum’s Window, in 1970. (The mixed notice in the New York Times Book Review was by no less an eminence than Alfred Kazin.) Markfield was a recognized pop-culture maven, writing for the Times Magazine on the persistence of burlesque, the significance of Walter Winchell, and the greatness of King Kong. In describing the “mad rushin’ to mama-lushen,” his Esquire essay “The Yiddishization of American Humor” not only anticipated Goldman’s “Boy-Man Schlemiel: The Jewish Element in American Humor,” but provided a road map for Goldman’s career.

Philip Roth appropriated a Markfield joke and name-checked him in Portnoy’s Complaint: “The novelist, what’s his name, Markfield, has written in a story somewhere that until he was fourteen he believed ‘aggravation’ to be a Jewish word.” (The story “Country of the Crazy Horse” was set in Markfield’s childhood Brooklyn and published in the March 1958 issue of Commentary.) A 1967 book review in the New York Times described Gershon Legman, the avant-garde Kinsey who wrote The Rationale of the Dirty Joke, as “a character in a Wallace Markfield novel,” which is pretty much what Markfield was himself.

Born in Brighton Beach and educated at Brooklyn College, he broke into print with stories in the Partisan, Kenyon, and Hudson reviews and book reviews in Commentary, achieving his first notoriety with an anti-High Noon diatribe, “The Inauthentic Western: Problems on the Prairie,” published by the American Mercury in 1952, a full two years before Robert Warshow would make many of the same points in his canonical Partisan Review essay, “The Westerner.”

To rehearse Markfield’s career—to even write that last sentence!—is to describe the world he would parody in To an Early Grave: A little-magazine critic named Holly Levine brags to an academic poet, one Barnet Weiner, about “the strong likelihood” that he will be teaching a popular-culture course called “From ‘Little Nemo’ to ‘Li’l Abner,’ ” and, when his frenemy jealously wonders if the subject is “like they say in the quarterlies, your métier?,” Levine angrily responds, “My piece on John Ford has been twice anthologized. Twice!”

Although this exchange escalates into a ’30s trivia competition that would prove Markfield’s defining literary trope, it was on the basis of “The Inauthentic Western” that he secured a regular gig writing about movies in every other issue of The New Leader (a “rightwing” socialist weekly of the David Dubinsky persuasion), where he had since 1949 been pondering serious works of literature and criticism, from Sholem Asch’s Tales of My People and Hemingway’s Across the River and Into the Trees to Irving Howe on Sherwood Anderson and a revaluation of Nathaniel West’s The Day of the Locust. (West, Markfield wrote prophetically, was a novelist who “never quite managed to produce a perfect work nor completely integrate his gifts, but one who was capable, nevertheless, of profoundly disturbing the reader.”)

So, the job only lasted six months—from late November 1952 into May 1953—Markfield got to publish 13 columns, among them a Stanley Kramer take-down worthy of inclusion in the Library of America Anthology of American Film Criticism. Devoting a full column to praising Anthony Mann’s unheralded “routine” Western The Naked Spur and the follow-up to trashing George Stevens’ overblown Shane, opining on Danny Kaye and Sergei Eisenstein, taking note of the 3D craze-igniter Bwana Devil, the Jazz Singer remake, and Stanley Kubrick’s debut Fear and Desire, Markfield showed excellent range and natural talent. His takes were knowledgeable, his language punchy, and his leads lively. Ironically characterizing himself as a “condescending cineaste” who would “choose the bleakest Randolph Scott Western over High Noon,” Markfield had an attitude that was a promising work in progress.

Like revered Nation critic James Agee, Markfield mourned the death of movie comedy (although his idols were not Chaplin and Keaton but the Marx Brothers and W.C. Fields). Like the two-fisted slang-meister Manny Farber, Agee’s New Republic rival and successor at The Nation, Markfield presented himself as a discerning populist, tweaking the “overly-cultish audiences” who patronized “cushy avant-garde theaters” for revivals of old Marcel Pagnol films and complaining that “a genuine love and deep feeling for the movies” were increasingly “hard to come by.”

Markfield championed apparent junk like The Magnetic Monster (“paced like a supercharged engine by director and co-author Curt Siodmak, this story of an unmanageable radioactive element—driven by an omnivorous appetite for the planet’s supply of electrical voltage—emerges almost as technological choreography”) and debunked pretentious tripe: Advising his readers that even the worst films may contain “an oddly haunting strain of excellence,” he pointed out that John Huston’s Moulin Rouge was not one of them.

And then, perhaps sensing Markfield muscling in on his turf, Farber called him out. Five years before Farber’s “Underground Film” would appear in Commentary, Markfield’s “Notes on the Great Audience” was an appreciation of Times Square grind-houses that glorified the instincts of their lumpen patrons in terms at once sentimental and condescending. It was “a classic case of what happens when a critic turns sociologist,” Farber wrote, chiding Markfield by name as he pointed out that the critic’s duty was “to encourage moviegoers to look at the screen instead of trying to find a freak show in the audience.” (Later that year Farber would write his toughest appraisal of the movie-going public—a blast at the mediocrity of current Hollywood product titled “Blame the Audience.”)

Coincidence or not, “Notes on the Great Audience” was the last movie piece Markfield would write for The New Leader (although, ironically, it was Farber’s put-down that prompted me to search out Markfield’s film criticism). It was a shonde to be sure that when The New Republic found itself casting around for a film critic four years later they hired not Markfield but a 24-year-old University of Chicago instructor named Philip Roth—yes, What’s His Name’s future rival, wrote movie reviews too, albeit less the subject for a doctoral dissertation than a footnote.

Beginning with a Funny Face blow-off in June 1957, Roth published 13 movie and television reviews in TNR. He got off some good one-liners (ending a review of Raintree Country with the observation that Eva Marie Saint “does the best she can with a role that could hardly have been individualized unless, perhaps, it had been played by Peter Lorre”) and used Henry King’s lumbering prestige adaptation of The Sun Also Rises as the pretext for an amusing Hemingway parody. Still, the TV pieces, including an analysis of Sid Caesar and an account of the 1957 Miss America pageant, are far better than the movie reviews, which, despite an amused appreciation of Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?, are largely oblivious to cinematic qualities and mainly discussions of plots or performances. Roth’s last review, published in February 1958, was another Hemingway adaptation (A Farewell to Arms) and one of the few in which he bothered to identify the movie’s director or even its screenwriter.

Markfield meanwhile was at work on the short story that would implant itself in Alex Portnoy’s mind. His last major piece on movies, “By the Light of the Silvery Screen,” was a position paper also published in Commentary in March 1961, a year before Film Quarterly ran Kael’s not dissimilar, “Is There a Cure for Film Criticism?” Markfield began with the observation that, given the absence of a canon or even an accepted notion that movies deserved serious attention, “the intellectual who turns film critic is letting himself in for a rough time.” Then, with a nod to Agee, Farber, and Kael, he proceeded to give Siegfried Kracauer and Parker Tyler, the twin pillars of American intellectual film analysis, a very rough time indeed—pillorying the former, the Weimar émigré who had more or less invented sociological film criticism with From Caligari to Hitler, for writing an aesthetic treatise on cinema; and the latter, a surrealist poet and author of Magic and Myth of the Movies, for daring to analyze Hollywood products as cultural dreams.

But if Markfield retired ingloriously from the fray, movies figure significantly in his three subsequent novels. In To an Early Grave, as the author would later describe it, “a pair of New York intellectuals test each other’s ability to call back, among other things, 17 movies wherein Bogart was featured but not starred: 9 actors who have played Tarzan; the last line spoken by Victor McLaglen in The Informer; and the name of the Ritz Brothers.” The father of the youthful hero of Teitlebaum’s Window is employed by a Brighton Beach movie-house, and the 10 years between 1932 and 1942 are individuated largely in terms of the era’s popular culture; in the wonderfully titled You Could Live If They Let You (1974), Markfield, having been compared (by Kazin, among others, and like Philip Roth) to a stand-up comedian, took a Lenny Bruce-like comic, interestingly named “Jules Farber,” as his protagonist.

Although dismissed by some as a plotless rant, the novel is actually Markfield’s most avant-garde, with Farber’s compulsive shtick hilariously filtered through the consciousness of the WASP academic who is studying him. The book’s first 44 pages are a comic shpritz unparalleled in the Markfield oeuvre: “My destiny was in the hands of—not Moses Maimonides, but Louis B. Mayer,” Farber raves, riffing on the representation of Jewish mothers in MGM’s biblical spectacles.

Once, only once show them watching a scale, yelling from a window, grating a little horseradish. You want to make Quo Vadis and Ben Hur? Go ahead, you’re entitled. Give a little boost, though to your own. It’s costing you anyway for a nativity scene, so punch up the Virgin Mary part. “Cheapskates, lice, pascudnyakim! You see my presents? Frankincense, myrrh. … I need it badly? I still got in my closet a jar garlic powder, it’s not even touched because by me spices are poison. Not even a box bridge mix, in Galilee they’re selling the best bridge mix fifty-nine shekels a pound. Do I care? I’m only embarrassed for the innkeeper.”

And so on.

Although Markfield must have known that, published a few months ahead of You Could Live If They Let You, Albert Goldman’s massive biography Ladies and Gentlemen, Lenny Bruce! would upstage his novel. Still, he gave the Goldman book a wonderfully generous New York Times review. You Could Live If They Let You was, on the other hand, slammed in the Times by Robert Alter, a long-standing foe of the Jewish American literary renaissance who used his review to knock Roth, Markfield’s fellow ethnic “mimic,” as well. “Farber intimates that reality itself may have become a hopeless mishmash of vulgar inanities,” Alter observed.

That apocalypse of kitsch has fortunately not yet arrived, but Markfield writes as though it were fully upon us, excluding all possibility of coherent narrative design, limiting fiction to a mocking imitation of trivia, an ambiguously ironic exploitation of nostalgic recall.

Perhaps. But not even so unsympathetic a critic could resist quoting some of Farber’s one-liners as when he gratuitously, if verbally, attacks some women in his audience: “Never never never be ashamed you’re Jewish … Because it’s enough if I’m ashamed you’re Jewish.”

At the same time as he inhabited the character of Jules Farber, Markfield was, for several years, the New York Times Book Review’s remarkably unenthusiastic go-to guy for books on movies. In a 1972 review of Robert Henderson’s scholarly press biography of D.W. Griffith, he asked for a “10-year moratorium declared by pundits and publishers on books in any way dealing with the motion picture.” And in a round-up of such books, published some 20 months later, Markfield made a distinction between the film historian and the “nostalgia addict” and declared himself firmly among the latter, citing a willingness to go his own “wild way” in responding to movies “without meditation or mediation!”

Moving over to the Times “Arts and Leisure” section, Markfield published a trio of pieces, over a six-month stretch of the mid-1970s, that mined his knowledge of Hollywood detritus. “Remembrances of ‘B’ Movies Past” is a creditable, annotated list of 10 outré classics from the ’40s and ’50s that quoted Farber and included both The Leopard Man and The Incredible Shrinking one. Ruefully citing the 5-page trivial pursuit passage in To an Early Grave as the defining accomplishment of his career (“camp turned compulsion for me”), Markfield next provided Times readers with a movie quiz: “In What Movie Did Marlene Dietrich Wear an Ape Suit? And Other Weightless Questions.”

“I’m now what critics and commentators nagged me into becoming these last 11 years: a ‘king of kitsch,’ a ‘seer of shlock,’ a ‘titan of trivia,’ ” Markfield complained á la Farber in a brief introduction to his quiz. Although To an Early Grave “had a thing or two to say about modern literature and literary men, one 5-page sequence drew a special kind of lopsided attention from reviewers [and] pretty soon those 5 pages were on the required reading lists of several sociology courses and anthologized in texts bearing such snappy titles as The Popular Arts: Aspects and Attitudes.”

Markfield claimed that he thought of passing this exercise off as either a new approach to “the problem of cinematic perception” or a secret chronicle of Hollywood movies. Indeed, a subsequent fun piece, “Hollywood’s Greatest Absurd Moments,” published in the “Arts and Leisure” section in January 1976, identifies him as working on just such a secret history. (It would be Markfield’s luck that he envisioned something along the lines of Robert Coover’s 1987 A Night at the Movies or, You Must Remember This, with its fabulously pornographic gloss on Casablanca, and that Coover beat him to it.) Perhaps Markfield abandoned his secret history; perhaps it was buried with him. In an alternate universe, it coulda been his masterpiece. - J. Hoberman http://www.tabletmag.com/jewish-arts-and-culture/109053/wallace-markfield-contender

Wallace Markfield, 75, Writer With a Humorous Sarcasm

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.