Kevin Davey, Playing Possum, AAAARGH! Press, 2017.

Playing Possum by Kevin Davey is an exuberant modernist reminder that T S Eliot was a fan of detective fiction, Charlie Chaplin and the music hall.

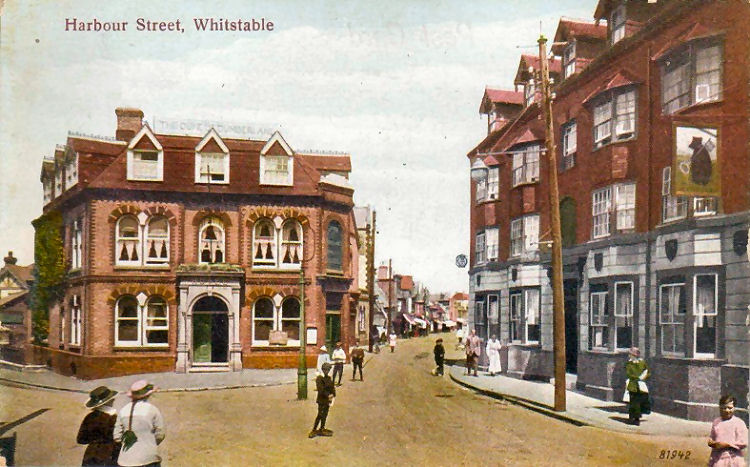

Fleeing from a violent incident in London in 1922, pursued by police, Tom spends a night in the Duke of Cumberland Hotel in Whitstable. Demobilised soldiers hold a meeting below his window and a silent movie is being shot on the seafront. Davey draws on local history and literature, songs, films and artwork from the period to produce a novel Eliot himself would have enjoyed.

Fusing the local history of Whitstable with reflections on T. S. Eliot and modernism, within a sort-of-detective narrative, Playing Possum is wild. Funny, dark, at once modern and nostalgic, the book is a rather like T. S. Eliot himself. This potential cult classic has already been shortlisted for the Goldsmiths Prize. - https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/public/republic-of-consciousness-prize-longlist/

‘Kevin Davey’s stupendous brain-teaser of a novel offers a stream of reflections on the life, work, thought, and mythology of T S Eliot… The novel is written with terrific fluency and tonal variety in a short-winded present tense, displaying a pronounced narrative emphasis on cinema, the art form that renders everything in a permanent now. He puts the mighty modernist back into his rowdy times, among the dancing and detective stories… Davey’s Eliot emerges as a creature and enabler of total fusion – an Anglo-American banker-poet desperate to conduct “the mind of Europe” in poems that eradicate the border between thought and feeling, plagiarism and originality, past and present, the classic and the new, populism and conservatism, high and low, rigour and impulse.’ - LEO ROBSON

‘This startlingly original debut novel has been shortlisted for this year’s Goldsmiths Prize alongside five other strong contenders – and deservedly so. In its formal daring and ludic complexity it aligns closely with the Goldsmiths’ remit “to reward fiction that breaks the mould or extends the possibilities of the novel form”… The book is an unalloyed pleasure, not merely for its myriad embedded references but for the light it throws on Eliots’s engagement with popular culture… Playing Possum is not just a spellbounding commentary on modernist writing but arguably a kind of apotheosis.’- DAVID COLLARD

‘I love the eddies and volutes of his anfractuous prose.’ - WILL SELF

‘A most stylish performance.’ - TERRY EAGLETON

‘Wonderful. What a joy to read a book like Playing Possum in the waste land of contemporary fiction writing in Britain. And how exhilarating to read a novel in English that is so serious it is not afraid to be comic and even at times absurd.’ - GABRIEL JOSIPOVICI

‘Playing Possum is a vastly energetic and confident book, a narrative that races along, packed with references and cross references mingling literature, film, time travel and visual art. Ninety years after the first publication of The Waste Land – and perhaps far too late – a modern day protagonist seeks proof of a murder and flight. A fictional investigator pursues a fictionalised – and murderous – T S Eliot from London towards a perhaps fictitious night spent at a hotel in Whitstable in 1922. The aftermath of his deed may have been immortalised in a suitably shocking painting by possible accomplice Otto Dix. Davey’s plot begins to tangle and gambol from the outset. The text – filled with dialogue, asides and allusions – is rich enough to repay rereading. Its time jumps and linguistic experimentation, its mosaic plot and dark humour is a joyful exploration of the novel’s boundaries as a form.’- A L KENNEDY

‘Playing Possum is hugely enjoyable and inventive. The precisely crafted prose crackles with exuberance, plays games with tones of voice, switches from po-faced parody to understated allusion. It is an exhilarating fairground big dipper of language and styles. I relished the energy of the writing and the inventiveness of the tale.’ - BERNARD SHARRATT

‘The year is 1922, the same year The Waste Land was published. That poem is famously made up of snippets of overheard conversation and found quotations and there is a large slice of this in Playing Possum too. Part of the pleasure for students of Eliot will be in tracing the references. The novel is full of the most astonishing and vivid writing. It’s almost as if the author is channelling the spirit of 1922 directly on to the page, as if he’s fashioned a time telescope through which we can look in on the scene 90 years earlier.’ - C J STONE

I’ve just finished reading Playing Possum by Kevin Davey. It is a new novel, set in Whitstable.

It is an intriguing book, but also quite disorientating as the story keeps fracturing across time and genre in a way that makes it difficult to know where you are.

I suspect this is deliberate. The central character is an American poet, Thomas Stern, who astute readers will quickly recognise as T.S. Eliot.

Eliot’s most famous poem, The Waste Land, was supposed to have been written in a shelter in Margate, and it is to Margate that our fictional character is travelling before his journey is cut short and he finds himself in Whitstable instead.

The year is 1922, the same year The Waste Land was published.

That poem famously made use of overheard conversations and found quotations, and there is a fair scattering of this in Playing Possum too. Part of the pleasure, particularly for students of Eliot, will be in tracing the references.

The novel reads like a series of clues to a story you have to construct in your own head and is full of the most astonishing and vivid writing. It’s almost as if the author is channelling the spirit of the dead directly onto the page, as if he’s fashioned a time-telescope through which we can look in on the scene all those years ago.

Most of the action takes place between the Duke of Cumberland and the Bear and Key and many of the events really did take place. So there’s a film, The Head of the Family, which was shot in Whitstable in the early 20s, and a political rally under a gas lamp between the two hotels, in the place known as the Cross, the forgotten omphalos of the town.

The novel also cuts to scenes taking place in the present, with drunken conversations of the sort you would recognise in any pub.

Our town is currently marking its place on the literary map. Not only do we have Julie Wassmer writing detective novels set in Whitstable, and a thriving literary festival, but there are an ever growing number of writers and artists working here as well.

Kevin Davey is definitely one to watch. - christopherjamesstonehttps://whitstableviews.wordpress.com/2017/06/29/whitstable-literature-playing-possum-by-kevin-davey/

opening remarks

Because Daniel Alarcon’s The King Is Always Above The People isn’t published until tomorrow* I’ve had to pause my National Book Award longlist reading and skip to one of the nominated books for the Goldsmith Prize, which, in this instance, is Playing Possum by Kevin Davey. The shock and horror – for me anyway – is that I’m reading a hard copy of this short novel. Actual paper. With binding and a cover. It’s discombobulating. I keep wanting to highlight paragraphs and phrases with my finger and when I press hard on a word I don’t get the option to check a definition!* “tomorrow” refers to the 31st of October. I started reading Playing Possum on the 30th.

knee-jerk observations

It’s taken a single page for me to fall in love with the language:

I shall now type out the back cover copy for Playing Possum:

“An American poet spends a night in Whitstable’s Duke of Cumberland Hotel in 1922. He is followed there ninety years later.”

So that’s clear as mud. And from what I’ve read so far it’s unlikely to get much clearer. Normally I’d find that frustrating, but in this instance, because the language is so playful, I find it exciting.

Actually, the novel isn’t as incoherent as I’m making out. The overarching plot takes places in 1922 and like the back of the book says involves an American poet.

It’s the way this is presented that makes for intriguing reading. For one the story unexpectedly jumps around in time to a man in a hotel room, the same hotel room our poet visited in 1922, researching (I assume) the murder. And in amongst that, blurring the lines between 1922 and the present day, are these flashbacks describing Tom’s (the poet) murder of Fanny (his wife) as if they were scenes from a film based on a famous murder, the screenplay of which may have been written by the author researching this brutal killing… or not. All this, cut and pasted together, creates a collage effect which isn’t as confusing as it sounds.

There’s something genuinely thrilling about never being sure where the next paragraph will take you. It’s also the sort of book that just for shits and giggles has a cop interviewing the Greek God of fire, metallurgy and crafts:

“An American poet spends a night in Whitstable’s Duke of Cumberland Hotel in 1922. He is followed there ninety years later.”

So that’s clear as mud. And from what I’ve read so far it’s unlikely to get much clearer. Normally I’d find that frustrating, but in this instance, because the language is so playful, I find it exciting.

Actually, the novel isn’t as incoherent as I’m making out. The overarching plot takes places in 1922 and like the back of the book says involves an American poet.

As I note below, the identity of the American poet went completely over my head.What the back cover blurb doesn’t tell you is that our poet murdered his wife. What begins with an accidental push against the wall ends, in a moment of rage, with a savage stabbing.

It’s the way this is presented that makes for intriguing reading. For one the story unexpectedly jumps around in time to a man in a hotel room, the same hotel room our poet visited in 1922, researching (I assume) the murder. And in amongst that, blurring the lines between 1922 and the present day, are these flashbacks describing Tom’s (the poet) murder of Fanny (his wife) as if they were scenes from a film based on a famous murder, the screenplay of which may have been written by the author researching this brutal killing… or not. All this, cut and pasted together, creates a collage effect which isn’t as confusing as it sounds.

There’s something genuinely thrilling about never being sure where the next paragraph will take you. It’s also the sort of book that just for shits and giggles has a cop interviewing the Greek God of fire, metallurgy and crafts:

I laughed out loud at the last line:

Playing Possum’s jarring shift in tone, topic and perspective keeps reminding me of Naked Lunch, just with less anal sex and junk. I have, though, learnt quite a bit about Charlie Chaplin and how he stole his shtick from Mabel Normand. Davey’s interest in Chaplin and old-timey Hollywood is just one of the eclectic obsessions in the novel.

In the context of this book the first sentence is very true:

The Gist Of It

Playing Possum should be a book that makes me feel small and ignorant. It’s only after I finished the novel that I discovered that it’s main character, an American poet who murders his wife, is actually a version of T.S. Eliot. I’m simply not well read enough to have joined those dots. (For one, up until 10 minutes ago I had no idea what the T and S stood for, now I know). There are other literary references ranging from Christie to Joyce. Ulysses was published in 1922 and so was The Waste Land by T.S. Eliot. The year is so important for the fiction that was published – and the reaction to that fiction such as Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (1925) that earlier this year Bill Goldstein wrote a whole book about it (The World Broke In Two).Although I didn’t pick these nods and winks, some more obvious than others, I still really enjoyed Playing Possum. With its fluid sense of time, merging 1922 with 2012, as if to imply that the more things change etc… and its fascination with Chaplin, the almost rise of socialism in the UK, the changing face of the countryside, the allure of silent film, and, to top it all off, a savage murder that proves to be the catalyst for what follows I just went with the flow. The language, so interesting and unexpected, the moments of absurdity and farce, the piling on of anachronisms, the utter lack of expectation, all of it coming together to create something that made me smile, that felt fresh and new even when it sometimes tipped over into pretentious gibberish. - http://mondyboy.com/?p=8571

Review by Leo Robson

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.