Elytron Frass. Liber Exuvia, gnOme, 2018.

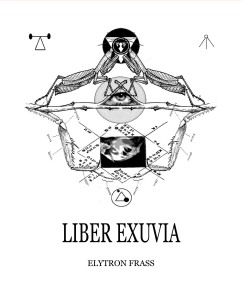

An interactive grimoire devoted to the sundry

incarnations of a self-beheading mantis, Liber Exuvia provides a shadow of

insight into its author by way of past-life regressions and encrypted charms.

What was once crudely printed and mass-mailed to random households all across

the globe—Elytron Frass’s confrontational novella is now bound, barcoded, and

available to any daring reader.

Liber Exuvia presents a hypnotic flow of morbid

visions of violence and sexuality that sometimes read like Comte De

Lautreamont, sometimes like 80s horror cult classics, and, most curiously,

often like beautiful lyrical poems, in which the poet is not ‘man speaking to

men’ but a conjurer of ghosts.” — Johannes Göransson

“Reading Frass’s work is the taking-in of a great

breath and holding it, stretching it to every seam, hallucinating as you beg

for air, and falling into a gentle death-lull of captivation. You will travel

to another world, many of them. You will leave your body with this book in your

hands. You will weep for history, weep for bodies, weep for your planet in the grand

scheme of existence. What beauty and terror is conjured here with such absolute

innovation of language and form! Frass tells stories, but does so from the

inside out, from a dream within a dream, planting you right in the center so

you can walk your way out. It is what writing should do.” — Lisa Marie Basile

The recent interest in the occult among certain writers shouldn’t be seen as nostalgia for a magical realm during a time – our time – in which magic has vanished. Rather, the new occult writing is interested in non-humanist modes of expression. It’s avant-garde. Like adherents of the cult of Cthulhu, writers of this new occultism are evoking an aesthetic that is simultaneously cosmic, ancient and uncannily new. In their hands, the human voice becomes what is always really was: alien, impersonal.

Liber Exuvia by Elytron Frass from gnOme Books is an intense channeling of these correlations (ancient/post human, occult/science). Frass, a writer and visual artist whose work has appeared in venues such as Tarpaulin Sky Magazine, has written a book that may be approached in a variety of ways: a mystic manual for past life regression, a fragmented narrative that blends the sensibilities of Lovecraft and Kenneth Anger, a series of dark meditations on evolution and its myriad pathways, both real and imagined. The title, like so much of the book, is associative and free ranging. “Liber” was the god of wine and festival in ancient Roman religion – a god that came to be associated with Dionysius. It also means “book” in Latin. “Exuvia” is the name of the exoskeleton left over after an insect or arachnid molts. In this way, the book stresses its own materiality – it is the spiritual exoskeleton of the creative process. The husk. The remnant. Presence marked by absence.

The first section of the book is a series of questionnaires entitled, ‘Synopsis of Statements Indicative of a Shared Past Life Regression’. Counter to the neoliberal emphasis on privatised notions of experience, Frass creates a list of questions describing possible past lives: lives lived across the globe, and at different points in history. Some of the past lives are female, and others male; some are singular, and other plural (“Long ago, I bifurcated into simultaneous lives”); some are human, and others are not (“Born from one of one hundred and eight eggs”). At the end of each line (for example, “Long ago, I was someone else”) there is Frass’ answer to the implied question Do you remember this? (in this case, “Y”). But there is also a space for you, the reader, to answer. This creates an odd doubling effect. Do the reader and Frass share past lives/experiences? Do the reader and Frass at times inhabit the same person, the same insect? This dynamic has occult elements beyond the “past life” aspect. The writer is not an “I” addressing an audience (the “you”). Rather, the writer reveals multiple fragmented lives, and asks the reader if they too have experienced these lives. There’s a whorl of voices and selves.

That so many of the lives presented break off into other lives – for instance, the relatively everyday Tim Peters, while under hypnosis, remembers a previous life in the ancient world dwelling among “herdsman and mercenaries”, and from there recollects his time in early twentieth century Portugal – lends the book an almost psychedelic aura, though a psychedelia with a folk horror edge to it. As the book progress, it becomes clearer that all of the lives and manifestations presented relate to the mantis – and specifically to the female praying mantis’ ability to devour the male while mating. Humans take on the attributes of the mantis, and vice versa, to the point where something elemental about this insect/human dynamic takes shape. The earth turns into a vast machine of perpetual, visceral becoming. The female praying mantis morphs into a divine figure, a phantasmal Sister Midnight. As Frass writes near the end of the book, “FREE ME FROM METEMPSYCHOSIS AND DUALITY / EAT ME WITH YOUR MANDIBLES / DEVOUR MY GENETIC AND LEARNED MEMORIES / FOR YOU ARE THE HOLY PREDATOR OF TIME/SPACE/CONTINUITY.”

In the following sections, the book becomes even more of a fantasia. Images of mantises overlaid and inlaid within human (and sometimes humanoid) figures, neo-pagan prayers, taxonomic names – all begin to appear, as if by filling out the questionnaires, by cycling through these various embodiments and experiences, we have reached a post-narrative plateau. The effect is half zine, half grimoire. The writer – or rather “Elytron Frass” – also makes a brief appearance in this section, in a down-the-rabbit-hole/House of Leaves/This House Has People In It style. We’re given a medical record from a Dr. “Cercus Comb” regarding the author’s fascination with (and belief in) previous lives. The doctor writes, “Today he expressed longing for whom he refers to as his ‘bifurcated self,’ or someone, somewhere, on this planet who mirrors his exact emotions, memories, and experiences.” Yet, I don’t think this “document” should be regarded as the key to this book, any more than one narrative thread in House of Leaves becomes the true route for the novel; the self-referential quality of the document, starting with the insect-like suggestiveness of the doctor’s name, highlights the artifice. Psychology isn’t being used to dispel metaphysics. Instead, the implication here is that psychology cannot be extricated from metaphysics. Our intuitions about reality relate intimately to our intuitions about the self.

There’s something implicitly subversive of this artifice, and of Frass’ project as a whole. Neoliberalism insists there is nothing outside the reality-principle – “experience” looks more and more indistinguishable from commodity, and there is a growing match-up between our conception of the “self” and our resumes. The atomised self is the marketable self. This might change, as science and technology increasingly undermines our human-centric assumptions about self and world, free will and culture. For now, books like Libra Exuvia suggest ways of thought and experience outside of what the late Mark Fisher called “capitalist realism”. These books allow us to catch glimmers of an alien light behind the human face. - James Pate

http://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/occultism-insects-alien-elytron-frass-liber-exuvia/

The Necropastoral is a non-rational zone, anachronistic, it often looks backwards and does not subscribe to Cartesian coordinates or Enlightenment notions of rationality and linearity, cause and effect. It does not subscribe to humanism but is interested in non-human modalities, like those of bugs, viruses, weeds and mold.The future might well be as nonhuman as the distant past, but said in a different register. Instead of spectres and physics, and instead of otherworldly voices, neural pathways and synapses. The current neoliberal brand of humanism – of the atomised “I” that pretends to be author to itself – might fade and be replaced by an experience of the world that is both older and newer. The more we learn about neurology, the less human we seem (if by “human” we mean free will and a centralised self-identity), and the more we know about space-time, the less crystalised “reality” becomes. Slowly, the human will be displaced from the centre. And the centre itself will be nothingness, emptiness. In the video to David Bowie’s ‘Blackstar’, the far future rhymes with the ancient past – the astronaut’s jeweled skull turns into an object of occult ritual. Time becomes a loop and not a line: a process torques within itself to become what it always was to begin with.

– Joyelle McSweeney, What is the Necropastoral?

Against the humanist world-for-us, a human-centric world made in our image, there is this notion of the world as occulted, not in a relative but in an absolute sense.

– Eugene Thacker, In the Dust of This Planet

The recent interest in the occult among certain writers shouldn’t be seen as nostalgia for a magical realm during a time – our time – in which magic has vanished. Rather, the new occult writing is interested in non-humanist modes of expression. It’s avant-garde. Like adherents of the cult of Cthulhu, writers of this new occultism are evoking an aesthetic that is simultaneously cosmic, ancient and uncannily new. In their hands, the human voice becomes what is always really was: alien, impersonal.

Liber Exuvia by Elytron Frass from gnOme Books is an intense channeling of these correlations (ancient/post human, occult/science). Frass, a writer and visual artist whose work has appeared in venues such as Tarpaulin Sky Magazine, has written a book that may be approached in a variety of ways: a mystic manual for past life regression, a fragmented narrative that blends the sensibilities of Lovecraft and Kenneth Anger, a series of dark meditations on evolution and its myriad pathways, both real and imagined. The title, like so much of the book, is associative and free ranging. “Liber” was the god of wine and festival in ancient Roman religion – a god that came to be associated with Dionysius. It also means “book” in Latin. “Exuvia” is the name of the exoskeleton left over after an insect or arachnid molts. In this way, the book stresses its own materiality – it is the spiritual exoskeleton of the creative process. The husk. The remnant. Presence marked by absence.

The first section of the book is a series of questionnaires entitled, ‘Synopsis of Statements Indicative of a Shared Past Life Regression’. Counter to the neoliberal emphasis on privatised notions of experience, Frass creates a list of questions describing possible past lives: lives lived across the globe, and at different points in history. Some of the past lives are female, and others male; some are singular, and other plural (“Long ago, I bifurcated into simultaneous lives”); some are human, and others are not (“Born from one of one hundred and eight eggs”). At the end of each line (for example, “Long ago, I was someone else”) there is Frass’ answer to the implied question Do you remember this? (in this case, “Y”). But there is also a space for you, the reader, to answer. This creates an odd doubling effect. Do the reader and Frass share past lives/experiences? Do the reader and Frass at times inhabit the same person, the same insect? This dynamic has occult elements beyond the “past life” aspect. The writer is not an “I” addressing an audience (the “you”). Rather, the writer reveals multiple fragmented lives, and asks the reader if they too have experienced these lives. There’s a whorl of voices and selves.

That so many of the lives presented break off into other lives – for instance, the relatively everyday Tim Peters, while under hypnosis, remembers a previous life in the ancient world dwelling among “herdsman and mercenaries”, and from there recollects his time in early twentieth century Portugal – lends the book an almost psychedelic aura, though a psychedelia with a folk horror edge to it. As the book progress, it becomes clearer that all of the lives and manifestations presented relate to the mantis – and specifically to the female praying mantis’ ability to devour the male while mating. Humans take on the attributes of the mantis, and vice versa, to the point where something elemental about this insect/human dynamic takes shape. The earth turns into a vast machine of perpetual, visceral becoming. The female praying mantis morphs into a divine figure, a phantasmal Sister Midnight. As Frass writes near the end of the book, “FREE ME FROM METEMPSYCHOSIS AND DUALITY / EAT ME WITH YOUR MANDIBLES / DEVOUR MY GENETIC AND LEARNED MEMORIES / FOR YOU ARE THE HOLY PREDATOR OF TIME/SPACE/CONTINUITY.”

In the following sections, the book becomes even more of a fantasia. Images of mantises overlaid and inlaid within human (and sometimes humanoid) figures, neo-pagan prayers, taxonomic names – all begin to appear, as if by filling out the questionnaires, by cycling through these various embodiments and experiences, we have reached a post-narrative plateau. The effect is half zine, half grimoire. The writer – or rather “Elytron Frass” – also makes a brief appearance in this section, in a down-the-rabbit-hole/House of Leaves/This House Has People In It style. We’re given a medical record from a Dr. “Cercus Comb” regarding the author’s fascination with (and belief in) previous lives. The doctor writes, “Today he expressed longing for whom he refers to as his ‘bifurcated self,’ or someone, somewhere, on this planet who mirrors his exact emotions, memories, and experiences.” Yet, I don’t think this “document” should be regarded as the key to this book, any more than one narrative thread in House of Leaves becomes the true route for the novel; the self-referential quality of the document, starting with the insect-like suggestiveness of the doctor’s name, highlights the artifice. Psychology isn’t being used to dispel metaphysics. Instead, the implication here is that psychology cannot be extricated from metaphysics. Our intuitions about reality relate intimately to our intuitions about the self.

There’s something implicitly subversive of this artifice, and of Frass’ project as a whole. Neoliberalism insists there is nothing outside the reality-principle – “experience” looks more and more indistinguishable from commodity, and there is a growing match-up between our conception of the “self” and our resumes. The atomised self is the marketable self. This might change, as science and technology increasingly undermines our human-centric assumptions about self and world, free will and culture. For now, books like Libra Exuvia suggest ways of thought and experience outside of what the late Mark Fisher called “capitalist realism”. These books allow us to catch glimmers of an alien light behind the human face. - James Pate

http://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/occultism-insects-alien-elytron-frass-liber-exuvia/

“Erotic in the most organic and tangible ways, Frass

manages to elicit such vicious imagery in so few words.” — Tina Lugo

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.