Mario Praz, The House of Life, Trans. by Angus Davidson, David R Godine; Reprint, 2010.

Mario Praz (1896 1982) was among the great scholar / critics of the last century. His studies of iconography and seventeenth-century art remain unsurpassed and indispensable. His most famous work, The Romantic Agony, examines the themes of sexuality and morbidity that permeated so much late-eighteenth and nineteenth-century literature. But The House of Life comes as close to his autobiography as anything we are likely to encounter, and it is a quirky and magical book. In simplest terms, it is a house tour, but Praz's Roman apartment was no ordinary house it was a wunderkammer, a house of wonders, rooms replete with objets d'art and sculpture, walls hung with paintings and prints, bureaus overflowing with postcards and ephemera. And Praz is no ordinary guide; he leads you, the reader, through each room lecturing on the objects therein. What emerge are his passions, his immense erudition, his insatiable curiosity, his undeniable amiability, his infectious enthusiasm. What might have been a predictable didactic exercise is transformed and expanded into a multi-layered disquisition on the nature of art, on the challenge of investigation and discovery, on the idiosyncracies of personalities, on the serendipitous way in which art and the objects we choose to surround us tell stories that go far beyond their purely physical attributes. Early on, Edmund Wilson recognized this book as a masterpiece, its author as something of a genius.

The House of Life is, I believe, his masterpiece a book unlike any other, and a much more complete expression of Mario Praz's sensibility than any of his other books. ... The apartment is not like a private museum, because it composes a unit, because, like the book which describes it, it is the intimate integument of Praz himself. The apartment is ''The House of Life'' because it is the house of Praz's life, and the description of his collections here is inextricable from the memories of his life. ... [Praz] will come to be known to posterity... as one of the best Italian writers of his time. - Edmund Wilson

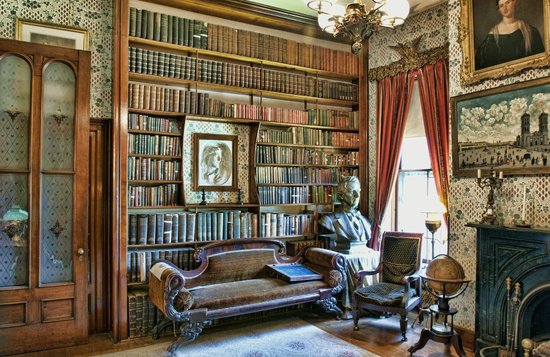

"In form, it is a description, room by room, object by object, of the ancient flat in the Via Giulia in Rome where Mario Praz has lived for thirty years. In effect, it becomes an intellectual and spiritual autobiography; for as he conducts the reader through the apartment, Praz recites the events of his life associated with the rooms and the furnishings he has so lovingly collected over the years. ... There has never been an autobiography written in this way. ... This is the story of the life of a connoisseur of art and of literature, serious but not solemn, erudite but very human." - https://www.mullenbooks.com/pages/books/153073/mario-praz-angus-davidson/the-house-of-life

The known writer and art and literatur critic Mario Praz didn’t only suffer the evil words by Cyril Connolly who said about the House of Life that it is one of the most boring books he ever read, a book so unbelievably exhausting. But also did he have the reputation to bring bad luck and was held responsible for sinking ships, broken lamps and other kinds mishaps, that happened wherever the writer appeared.

Of course his fans didn’t want to leave it at that and think that this interpretation of> his text is nothing more than an unlucky coincidence.

To them the house of Mario Praz in Rome is one of the most incredible museums of a writer and The House of Life – in which Praz analyzed the story of his wonderful collection – is far from a bad reputation. According to James Joyce this collection was a way for Praz to express the mystery about himself in his furniture.

He was one of the greatest experts regarding Antonio Canova and Baroque, as well as Neoclassicism and the history behind the decorations in Pompeji. Luchino Visconti dedicated a figure in one of his movies, Gruppo di famiglia in un interni (1974) played by Burt Lancaster to Praz.

- http://blog.only-apartments.com/mario-praz-house-of-life-rome/

In 1934 he went to live at the Ricci Palace, in the via Giulia. Then, that particular meander of baroque Rome lived tranquilly in a city of provinces. And the book, with a title as suggestive as The House of Life, tells the story of how that gloomy Roman palace, aged but noble, became filled with beautiful things, objects of the past found in European antiques markets. Empire-style furniture and small artefacts that the history of art with a capital 'A' considered simply to be 'art mineur' or at the very most decorative art. And there he spent his days in that over-refined setting, surrounded by trinkets, a little bit beyond life itself, like the reflected images of the Empire-style mirrors which decorated his house, and which the writer loved so much. They are, said Praz talking of the mirrors, like the glass of an aquarium which separates our own state from another, populated by silent creatures. Happy in his shipwreck - melancholy is the joy of being sad, said Victor Hugo - his life was blighted by the thought that true happiness was to be found elsewhere, in places never visited or seen, and for which he felt a profound nostalgia. The House of Life was a finalist for the 1958 Strega Prize, awarded to the prince of Lampedusa for The Leopard - a novel which was also made into a film by Luchino Visconti, with Burt Lancaster playing the part of a ruined aristocrat who the old professor in Gruppo di famigita in un inferno would later remind us of. This coincidence in the same literary event signified the meeting of two voices which belonged to the time of reflection during the postwar period, the moral landscape of Europe having changed, where writing seemed to be the only way to immortalize the old ways. The Majorcan writer Llorenç Villalonga, soul brother to the Sicilian Prince, was also have been tuned in to that time. Remember that what The Leopard and Beam, two books published simultaneously, have in common is the aristocratic decadence of two Mediterranean islands. To read any of these three authors is to return to a serene, balanced style of writing, that is to say neoclassical, which exudes clear nostalgia for the past, a lack of faith in the present, and curiosity for the future. It could be said that they lived convinced that the only paradise was paradise lost.

- DANIEL CID MORAGAS http://tweedlandthegentlemansclub.blogspot.hr/2010/10/empire-empire-mario-praz-house-of-life.html

We owe a lot to the artistic and literary studies of Professor Mario Praz (Florence 1896 – Rome 1982), to his in-depth and accurate analysis, with which he shed new light on so many works of art and literary trends, from Machiavelli’s reception in Britain and the Renaissance emblem books through the conceptismo of the Baroque, John Donne’s texts and Byron’s poems to the dark side of Romanticism or the reevaluation of bourgeois taste in the Biedermeier and Empire home interiors. His writings always move on the – strongly subjective – border area, where literature meets other art forms, to make together more livable a hostile world. By this effort Praz also intended to fill the emptiness of the second part of the twentieth century, which he abhorred, and where he felt completely alien.

One of his most personal books is La casa della vita (“The House of Life”, 1958, enlarged edition 1979), which is an essential document to understand who Mario Praz was, and how he saw himself. In this book he does not conceal the dark sides of his own life and character either. The ambiguous title is also a reference to the innermost and most hidden part of the Egyptian temple, where the secret texts and ceremonies were hidden from the external world. Praz talks along multiple threads about how he constructed his life around his objects, friendships, loves and manias, and behind this becomes clear the melancholic loneliness pervading all his life. As he moves through the rooms of his home, he gradually unfolds the fabric of his life, keeping a delicate balance between the detailed technical description of the objects of a passionate collector, and a highly personal, intimate and self-critical revelation of himself. A fascinating book, unique in its kind. And one cannot put it down: we have read it in a single breath. In the year of its publication it was presented to the Strega Prize, but, to Praz’s misfortune, Lampedusa’s The Panther was also published in the same year. Luchino Visconti drew inspiration and details from this book to his film Gruppo di famiglia in un interno (in English Conversation Piece). But, for a balanced opinion, we should not overlook Cyril Connoly’s judgment, who wrote a criticism on 20 September 1964 for the Sunday Times about the English translation of the book:

“One of the dullest books I have ever read; it has a bravura of boredom, an audacity of ennui that makes one hardly believe one’s eyes […] He has an ant’s eye view of small objects, an overwhelming sense of their importance in relation to himself and viceversa […] his disseminated egotism, his fulminating cliché…”With which, of course, we do not agree. If nothing else, the magnificent and melancholic report about the vanishing Rome – specifically, Via Giulia and the surroundings of Palazzo Ricci – makes the book worth reading. Mario Praz moved here in 1934, and in 1967 he had to remove to Palazzo Primoli. To date, the remaining objects of his huge collection are on display in the latter apartment. Here he died on 23 March 1982, thirty-three years ago today. A few weeks ago we also went to see “the House of Life”, to pay a tribute in our modest way. - riowang.blogspot.hr/2015/03/the-house-of-life.html

The House of Life, by Mario Praz (translated by Angus Davidson): What is Mario Praz’s non-fiction book The House of Life doing on this list? I have no burning desire to inflict it upon other readers, and I can guarantee it won’t be to many people’s taste. But The House of Life certainly was one singular reading experience. The book’s rather pretentious premise - a room-by-room guided tour of Praz’s private collections within his Roman palazzo - is quite nearly a literal invitation to come up and see his etchings. This does not, on the surface, sound promising. Cyril Connelly called it among the dullest books he’d ever read, "a bravura of boredom, an audacity of ennui that makes one hardly believe one's eyes." Indeed, it seems the kind of thing that only a dealer in antique furniture, clocks, decorative paintings, bric-a-brac, etc. from across Europe might find fascinating. Unexpectedly, however, so did I. Into Praz’s seemingly never-ending catalogue of objects, he weaves stories associated with or associations set off by them, and one never quite knows where he’s going to go, whether recalling an assignation, quoting Eugenio Montale on Italo Svevo or delving into some fascinating, hidden corner of history. The book itself, with several fold-out color photographs of the rooms, is beautiful. I learned a hell of a lot about European culture and more about interior decorating than I ever expected to know, from a writer widely regarded as one of the great critics of the subject. In the end, The House of Life becomes a strangely hypnotizing meditation on materiality, on beauty, on why objects matter to us and why they seem to matter so much, particularly given Praz’s observation that “with human beings, things do not go so smoothly.”

http://seraillon.blogspot.hr/2018/02/re-emerging-best-of-2017.html

Mario Praz, The Romantic Agony, Meridian, 1956.

full text

In this now-classic study, Praz describes the whole of Romantic literature under one of its most characteristic aspects, that of erotic sensibility. This wide spread mood in literature had a major effect on 19th-century poets and painters, and the affinities between them and their 20th-century counterparts makes this account of the Romantic-Decadents an indispensible guide to the study of modern literature.

Mario Praz, Mnemosyne: The Parallel Between Literature and the Visual Arts, Princeton University Press, 1975.

https://monoskop.org/File:Praz_Mario_Mnemosyne_The_Parallel_between_Literature_and_the_Visual_Arts.pdf

In 'Mnemosyne' Mario Praz explores and exhibits that close relationship between the arts-based on the unitive sense of reality and experience... that has been apparent intermittently for the 25 centuries since Simonides. It shows how widespread this phenomenon has become over the centuries.

'Mnemosyne' is really a tour down the centuries through galleries, libraries, churches, gardens, and salons, which at every point opens up surprising and penetrating views

Mario Praz, An Illustrated History of Interior Decoration: From Pompeii to Art Nouveau, Thames Hudson, 1981. + 2008.

The appeal of this extraordinary book lies in its rapt obsession with the details of the domestic interior, borne out in a wonderfully rich collection of pictures. These charming paintings and watercolors, mostly dating from 1770 to 1860 and coming from all over Europe, Russia, and America, record with faithful accuracy the shape of a room, the pattern of a carpet, the furniture, pictures, fabrics, and wall coverings, the hang of the curtains and the fall of the light they admit.

The pictures find their place in a complete survey of domestic—and some more palatial—interiors portrayed in art from the ancient world to the late nineteenth century, and including works by Vermeer, Hogarth, Durer, Degas, and Vuillard. The text goes beyond scholarly commentary to present an evolving picture of men and women in relation to domestic surroundings, full of human interest, wit, and wide-ranging cultural references.

By nature I am not at all covetous. If Santa Claus were to bring me the Mona Lisa, the Rokeby Venus of Velazquez and Michelangelo's standing figure of Moses, I should return them to their lawful locations without a moment's regret. Where I would readily turn to a life of crime, on the other hand, is in pursuit of a subdepartment of European painting in which until lately almost no one was interested - the small domestic interior, that is to say, as it was portrayed between 1790 and 1830. I would take it singly, where I could find it, but above all I crave the albums that lie around in so many great European country houses. In those albums the look of the inside of the house was recorded in watercolor by one generation after another. Major art they are not, beyond any question. But minor art has also a spell to cast.

It so happens that I shared this predilection with Professor Mario Praz, the Roman historian, connoisseur, collector and covert autobiographer who died earlier this year at the age of 86. Praz had read everything, looked at everything and forgotten nothing. On Milton and George Eliot, John Donne and the Marquis de Sade, he was unbeatable. He knew all that there was to know about architecture, painting, furniture, bronzes and porcelains. He knew all about the river Tiber in Rome, and all about its diminutive namesake in Washington. He had by heart the intimate history of every great family in Europe. He was immensely, impossibly, almost unbearably learned.

But on our few and brief meetings we did not discuss Byron or Flaubert, Metternich or Delacroix. We discussed Kretzschmer and Pflug, Ivanov and Venetsianov, Puskarev and Klaestrup. Runty little names like Shrank, Bendz and Blunck flew back and forth. These were the names of our favorite painters of interiors; and although Mario Praz was believed by everyone in Rome to have the evil eye, and to be able therefore to cast a malefic spell on all who approached him, I never hesitated to look him full in the face, such was the shared rapture of our superheated exchanges.

Praz was known above all for ''The Romantic Agony,'' a study of European Romanticism that caused a great stir when it was first published in English in 1933 and has since become something of a classic. It is remarkable both for the originality and penetration of its insights, for the almost manic resource of its documentation and for the tranquil persistence with which he dismantled the traditional view of the Romantic Movement and substituted for it something darker and more disquieting.

But then from 1925 until almost the day of his death he was out to sow doubt and disquiet among students of poetry, painting and the novel. If he could give them an uneasy night, he never failed to do so - not least perhaps in the wonderful book called ''The House of Life,'' in which he took us round his rambling apartment on the Via Giulia in Rome and told us exactly what was in it, and why, and what it meant to him.

''The House of Life'' has long been out of print in English, but the good news from the late summer lists is that Thames & Hudson, Inc., has brought out a new edition of one of the most remarkable of Praz's later books. It is called in English ''An Illustrated History of Interior Decoration from Pompeii to Art Nouveau.'' Translated from the Italian by William Weaver, it has 400 illustrations - 64 of them in very good color - and it costs, alas, $75.

The English title is one that will sell the book, I don't doubt, and to that extent I applaud it. But it isn't what the book is about. It has nothing to do with interior decoration as it has been carried out by professionals - some of them wonderfully gifted - in our century. Not one of the 400 interiors was put together by a specialist on behalf of a client, that is to say. Nor can this claim to be a comprehensive survey of historic European interiors, for it is weak on the French 18th century and weaker still on the age of Robert Adam in England. Much as I myself dislike Versailles and dread going anywhere near it, I really don't think that it should be omitted entirely from an illustrated history of interior decoration.

Nor could one truthfully recommend the book to the householder who has it in mind to stun the neighbors with some spectacular refurbishing. We are all free to fantasize, and nowhere more so than in our own homes, but I doubt that many readers of this book will wish to imitate the austerity of Goethe's workroom in Weimar, the curious high-colored bareness of the apartment occupied by the exiled Empress Marie-Louise in Parma, or the uncarpeted apartment in Copenhagen in which life for the ladies was one long wordless sewing bee and the master of the house was so deep in the latest scientific review that he never so much as opened his mouth.

As far as interior decoration is concerned this is in fact a book for daydreaming, rather than for action. But what daydreams! What other book can whisk us so assuredly all over pre-industrial Europe, from the childhood home of the poet Shelley in England to the cabin of a riverboat on the Volga, and from the studio of Ingres in the garden of the Villa Medici in Rome to the study of the Emperor Francis I of Austria-Hungary in Vienna? There is in the second half of the book a degree of emotional commitment that is rare in surveys of this kind. As with everything that Praz wrote, we feel at once that he is sharing with us something that is almost too private to be set down on paper. So far from being the kind of book that could be put together by an experienced picture editor and written to order by a pliable hack, this is a European document of the first order, and was intended as such by its author.

The earlier half of the book includes many images by major painters - among them Pietro Lorenzetti, Rogier van der Weyden, Hans Memlinc, Vittorio Carpaccio and Jan Vermeer - as well as paintings and engravings by lesser masters. When treated as indexes to the everyday life of the periods in which they were executed, these never fail to yield something of interest. But most of them exist on an imaginative level that hoists us above and away from the immediate purpose of the book. There is really something rather perverse, for instance, in looking at Rogier van der Weyden's ''Annunciation'' in the Louvre primarily for what it has to tell us about the role of the chimneypiece in a 15th-century Flemish interior.

If the balance of the book is weighted, therefore, towards the late l8th and early 19th centuries, the reason is that it started life as an extended essay on ''The Philosophy of Furnishing'' (a title that Praz lifted from Edgar Allan Poe). Praz began work on this essay in October 1944, at a time when much of what he loved most in Europe lay in ruins and quite a lot more was still slated for destruction, and he wanted to set down his feelings about the European interior before it was too late.

What he produced was not a guided tour but a series of prose elegies. (It had, in fact, much in common with ''Metamorphosen,'' the requiem for a devastated Europe on which Richard Strauss embarked at much the same time.) ''The Philosophy of Furnishing'' was published on its own in 1945, and although it was revised for the present edition, it still stands as one of the most poignant of messages from the Europe that had still to see the end of World War II. For Praz really meant what he said - that ''As long as there are four walls that still keep the aroma of our vanished Europe, it is among those four walls that we wish to die.'' - John Russell http://www.nytimes.com/1982/08/29/books/art-view-mario-praz-a-philosopher-of-european-interiors.html

An explorer of the darker byways of nineteenth-century life and letters (English, French, German, and Italian), Praz mapped out territory into which no academic had previously ventured. As an amateur of the visual arts he sought out the bizarre, the grotesque, or what were still, to other eyes, forbidding if not forbidden subjects. The Neoclassical marbles and Empire furniture and bibelots that were unfashionable when he began to collect and write about them appealed to him precisely because they put the spectator at a distance, discouraging intimacy or—per carità—any hint of coziness.

Until late in his career Praz was better known and more highly regarded in England and America than in Italy, though always as a foreigner uniquely placed to illuminate English literature from unfamiliar angles and set it in a European perspective. English translations of his books include Machiavelli and the Elizabethans, The Romantic Agony, Studies in Seventeenth-Century Imagery (an account of emblem books), The Hero in Eclipse in Victorian Fiction, The Flaming Heart (studies in Anglo-Italian literary relations from Chaucer to T.S. Eliot), On Neoclassicism, his autobiographical The House of Life, and An Illustrated History of Interior Decoration. Few if any other twentieth-century Italian writers of non-fiction have had their works as widely diffused in the English-reading world. By the early 1950s he had become, to use a nineteenth-century term of the kind he savored, one of the “lions” of Rome sought out by foreigners—almost on a par with Michelangelo’s flawed Pietà, which the persevering could then visit in a nondescript house in the suburbs after ringing a doorbell marked “Rondanini.”

The lair in which Praz had gone to ground was, however, in the very heart of vecchia Roma itself. I well remember going to see him there some thirty years ago, in the large apartment in the Via Giulia where he lived alone. The atmosphere was slightly northern, reminiscent of the Gedenkstatte of some early nineteenth-century German writer, despite the aged and Caravaggesque Perpetua (another now vanished species) who unbolted the enormous creaking front door and ushered one through several shuttered rooms into a great high-ceilinged salone. There one was received by a shabbily dressed man with courteous formality as if by a rarely disturbed custodian. But Praz soon surprised me by producing a set of photographs… - Hugh Honour http://www.nybooks.com/articles/1983/03/03/from-the-house-of-life/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.