Victor Rodríguez Núñez, tasks, Trans. by Katherine M. Hedeen, co-im-press, 2016.

Víctor Rodríguez Núñez's tasks [tareas] is an award-winning poetry collection, the recipient of Spain's Rincón de la Victoria Prize in 2010 and published there by the prestigious press Renacimiento in 2011. With striking images and memorable verses, tasks creates a testament to the poet's unique migratory experience. While seemingly the chronicle of an immigrant who returns to his native country, the poem really asks how to return if you've never actually left. Using rigorous formal aspects to create a sense of pushing beyond known limits, this innovative long poem has at its core a rethinking of the experience of otherness, in which identification—both with memory and quotidian experience and with place tangled in subjectivity—prevails over any kind of differentiation. This leads not only to a profound questioning of nationalism but also of cultural identity itself. The result, which Katherine M. Hedeen renders for Anglophone readers, is a fluid poetic subject who disrespects borders and privileges movement over fixedness.

“… I’m / a phantom in this barbershop / mirrors eaten away by shadow” Víctor Rodríguez Núñez tells us in Katherine Hedeen’s magnificent translation. And later: “I linger in the snow a royal palm on my shoulder,” and still later: “identity lurks / like a forgotten ring in a public bathroom.” These poems are intimate and historic, woven of memory, inhabiting a space that invites the reader in. This is the voice of a mature poet, a Cuban straddling the century in which his country rose about him, lifting him on shoulders of discovery, loss and everything in between. Rodríguez Núñez is one of his generation’s most powerful poets, tasks among his most satisfying books, and Hedeen’s English renderings nothing short of magical. —Margaret Randall

The imagination of this Cuban, this true poet … stains the darkness of these times with a red squirrel guided by the light … Víctor Rodríguez Núñez doesn’t wait for the arrival of anyone because he was baptized by poetry at birth. —Juan Gelman

Víctor Rodríguez Núñez is a poet after my own heart, a nomad witness who after the long reasoned zigzag dérive through senses & cities, tropics & topics, stands by de Greiff’s sense that “all journeys, all my journeys, are return journeys.” […] The poet is indeed a master of the craft of otherness.

—Pierre Joris

—Pierre Joris

A Cuban poet who has spent much of his adult life outside Cuba, Rodríguez Núñez takes to all he sees and feels in poetry a consciousness of Cuba as place, as communities, and as a country isolated from his adopted home in America, as a form of restraint and dynamism […] I cannot speak highly enough of this poet. —John Kinsella

I often find myself explaining my desire to translate by expressing that it is an inherently collaborative project, one in which my voice gets to support another’s. tasks, which was longlisted for the 2017 Best Translated Book Award, is the most recent, luminous product of years of collaboration between poet Víctor Rodríguez Núñez and translator Katherine M. Hedeen. Hedeen has translated several of Rodríguez Núñez’s books, and they’ve worked together on translations of English-language poets into Spanish (Mark Strand, John Kinsella), and vice versa (Juan Gelman, Ida Vitale). It’s clear that this foundation set Hedeen up well for taking on the task of tasks (couldn’t resist!) and bringing to an Anglophone audience this impressive book in which a “shift toward a new poetics solidifies” (x).

That shift, as Hedeen describes it in her translator’s note, is primarily formal, which then opens the book to new content. Rodríguez Núñez’s lack of punctuation or capitalization leads to “edgeless poetry,” a “radical rebellion against coherence” (x). And there is indeed a kind of beautiful openness to these lines, making this a poetry that’s wonderfully difficult to categorize. At times it relies on pure image: “the sparrow interrupts / the candle stub / penumbra let loose,” while other lines feel like a memoirist’s descriptions in the voice of the poet himself: “I had to go for the milk churn / before breakfast / get soaked in dew” (109, 16-17).The book has a complicated relationship with memory. In the poem “[presents],” a line in the first stanza reads “this isn’t nostalgia it’s past,” and in the second stanza reprises it with “this isn’t past it’s nostalgia” (57). Though Rodríguez Núñez writes, “I don’t always write about Cuba or in Cuba, but always from Cuba,” the reader of tasks feels the back-and-forth tug of moving between places, of being suspended in flight, of carrying memories, of defining oneself in and away from a place of origin (x).

Hedeen is the kind of translator who trusts her readers with this in-between. She leaves in Spanish, without footnotes or with only the most unobtrusive of glosses, the many specific names of flora, fauna, and other culturally specific nouns which give these poems their grounding in Rodríguez Núñez’s Cuba. For example, in the poem “[filiations]”:

my mother mends her soul with palm fibers

her sight falls short

her sight falls short

but she’s got being to spare

she lives to keep company

she’s yagua in the uproar

she’s yagua in the uproar

a truss of palmiche (81)

The reader is trusted to know or look up “yagua” and “palmiche,” while through these culturally specific words the poem is allowed to remain true to the poet’s experience, unmediated.A few lines later, the speaker’s uncle is described as “southpaw cabinet maker uncle” (81). This is a good example of how Hedeen chooses to deploy English in her translations—she looks for fresh ways to say. I had to look up “southpaw,” and I love it when literature makes me do this. In this way, Hedeen is my favorite kind of translator—she lets English be its most capacious. Other good examples of this kind of translatorial work are in many phrases for which Hedeen finds colloquial options in English. One example: “an innocent void / turns out nouns like soot” is Hedeen’s rendering of the lines including the Spanish verb “produce”—no boring cognates allowed in this translation (29)! In addition to rich vocabulary and work with syntax, attention is also paid to sound: satisfying vowels and chewy consonants. Occasionally, these translations tip a bit too far into alliteration for my taste, when alliteration is not the technique used in the Spanish: “over the blue stumbling / shallow sky / shipwrecked sands” for the Spanish “que en el azul tropieza / cielo de bajo fondo / arenas naufragadas” (64-5).

In Hedeen’s translation, we get another take on the politics of the original text. There are quite a few lines that specifically refer to politics, such as:

my homeland isn’t anthologies

don’t forget I’m a tojosista

all that counts are the pages salvaged

from a bare-bones economy (7)

In aligning himself with the tojosistas (outsider poets writing in the periphery of urban areas, around the time of the Cuban Revolution), and critiquing the economy, Rodríguez Núñez lets the reader in on his political stance. Hedeen’s choice of the expression “bare-bones” for “subsistencia” in the Spanish further highlights the gravity of the Cuban economic environment. “The tropics are naturally socialist,” Rodríguez Núñez writes in another poem (113). In the poem “[indisciplines],” he remixes the Communist Manifesto slogan “¡Proletarios de todos los países, uníos!” (Workers of the world, unite!) thus: “workers of the world / only leisure unites us” (43). “Trabajan” (literally, “they work”) becomes the more forceful “they slave” for emphasis (43). In fact, the labor/leisure divide forms a major thematic aspect of tasks.don’t forget I’m a tojosista

all that counts are the pages salvaged

from a bare-bones economy (7)

tasks, it must be said, has the best cover design of any book of poetry I’ve seen in a long time: it is yet another beautiful object created by co•im•press, a growing small press whose founder, Steve Halle, is incredibly devoted to publishing work in translation. It’s very striking, and captures much about the book. The warm colors suggest the tropics. A skeleton bird form overlays a live chicken, indicating the phantom self the speaker references in various poems. The skeleton is pecking at a shell, its morbid task, while the live chicken stands idle, at leisure. A chick skeleton lies unhatched inside another shell, suggesting either progeny or death and decay, two dark forces that are often beneath the surface of the poems in this book. The tasks presented in tasks are the human ones—remembering, forgetting, mourning, loving, recording. - Kelsi Vanada https://readingintranslation.com/2017/06/22/island-under-our-skin-tasks-by-victor-rodriguez-nunez-translated-by-katherine-m-hedeen/

How does an immigrant return to their native country if they’ve never actually left? Cuban poet Víctor Rodríguez-Núñez asks this timeless (and timely) question through twenty-one sections that make up the long poem tasks, translated masterfully into English by Katherine M. Hedeen and published by the exciting co-im-press.

In terms of describing tasks, I honestly don’t know where to begin—and this seems to be exactly the point: experiences, like Rodríguez-Núñez’ lines, are without beginning or end, borderless and beyond differentiation:

beards half a century old

scissors dread me

I’m hardheaded

I’m from another dream of roosters crowing

raccoon bandit

hygiene of bathrooms both exotic

not so much as a volcano

a sooting of flurries

I’m a blue mark in the silence

freshly cut grass flamboyant trees

wonders of doubt

in the mirror there’s someone gazing back

ransacked by the light

an old acquaintance

—attempted excerpt from the section “origins.”Through the elimination of commas, periods, and uppercase letters (save for proper nouns and the “I” in translation), Rodríguez-Núñez moves toward a form which he in the book’s introduction calls “edgeless poetry.” Indeed, it is difficult—sometimes impossible—for the reader of tasks to find a point where an idea begins or ends, and it’s exactly within these limitless impossibilities that new meanings and magical images emerge from the text. Rodríguez-Núñez and Hedeen leave the reader hanging in a compelling cloud of disorientation—guided by question marks as the only sentence-splitting punctuation—throughout the book:

what does the peasant

right in the middle of a furrow

weeds no longer relevant

facing the freeway

where cars hum

for a moment head-raised want to tell you?

that it’s rained and the corn is coming up strong this year?

that the sun’s yolk

has just burst the horizon

starry with palms and agave flowers?

that the task is hard

and you won’t write about all this?

tulips glimmer

only proof the sun survives

leaves aren’t tame

they turned to glass in the night

when the workers cut the grass

—attempted excerpt from the section “indisciplines”.Although memory perpetually haunts the quotidian, a comforting regeneration of nature always surrounds the narrator’s experiences. tasks deserves to win the Best Translated Book Award 2017 because it reads like a stunning, hopeful requiem—or a cut-up poem crafted from the transcript of a roundtable discussion between Federico García Lorca, Inger Christensen, and The Kinks—presenting an imaginative remix of otherness and eco-poetics in a carefully crafted form where words, like migratory birds, roam freely across borders. - Katrine Øgaard Jensen http://www.rochester.edu/College/translation/threepercent/index.php?id=19482

“I am absolutely against nationalism,” Víctor Rodríguez Núñez tells Katherine Hedeen, his colleague and translator, in Asymptote. “In my view it’s a completely perverse ideology that’s justified humanity’s greatest crimes.” He continues, “There’s no reason for me to limit myself. I can leave the island and still be Cuban, but differently, and that’s exactly what I want to be.”

Rodríguez Núñez makes his home away from Cuba in Ohio, where he has taught at Kenyon College since 2001. Gambier, Ohio, is a far cry from Havana, not only because of the differences between cultures and languages, but also between the landscapes themselves. From the February snow of the Middle West and the voracious sun of the Caribbean, the silent corn huddled in sentry and the metropolitan energy of an island capital — place, culture, and identity exist in a close-knit system of mutual influence. The poet conserves his private rendition of Cuban identity, insists that he can “still be Cuban, but differently.”

How does an artist make sense of these contradictions? How does one refuse the violent baggage of nationalism but embrace the influence of genius loci? Like so many expat authors before him, Rodríguez Núñez finds intimacy in the distance and familiarity in the gradual, inescapable forgetting:

The poems in Rodríguez Núñez’s award-winning volume tasks invite the reader to a Cuba of recollection, of disjointed, misremembered encounters and vague impressions challenged by his later visits back to Cuba. This mindscape exists for the poet to trace the imperfections of his own memory as if tracking a lost cat through the old neighborhood only to find that, no, there never was a cat. The poems are dense and reflexive until his verse breaks open to reveal a lucid scene, as in the opening lines of “[indisciplines]:”

“Here for the first time Rodríguez Núñez eliminates uppercase letters as a marker for units of meaning,” Hedeen writes in her translator’s introduction. “This change in form has profound implications for content, a radical move toward a new form the author calls ‘edgeless poetry.’ No limits to sense, no point where an idea or image begins or ends, the greatest fluidity of thought possible. And so, it’s not just verses, stanzas, or poems that are enjambed, it is meaning itself.”

This may be a slight overstatement. Many if not most of the lines stand as discrete semantic units that build one upon the next into a difficult but mostly accessible coherence. The verse is evocative and at time overtly political: “a squirrel’s more mindful than a government minister,” he writes. “you give it a nut it saves it asks for another / and it’ll eat even when it’s full / the tropics are naturally socialist”.

The central innovation of Rodríguez Núñez’s verse seems to stem not from his composition or the turns of phrase — often striking in both languages — but from his employment of the line break and his omission of both capitalization and much of the punctuation. By disjointing grammar, words (especially verbs) teeter at the end of certain lines, where they masquerade (as reflexive or transitive, for instance) before the following line casts its new, often revisionary spotlight. Take for instance this passage from the first poem in the collection, “[origins]:”

Hedeen’s translations are crafted and thoughtful — although she misses an opportunity here for the frisson of “after all I am,” a phrase which relates the postnationalism and nostalgic confusion of the volume as a whole. One instance aside, her translations represent the Spanish poems in verse that is still poetry when it finally arrives in English, and that is no small accomplishment.

Rodríguez Núñez challenges the translator with daisychains of observation, interior monologue, and disjointed reflections. These poems take the day-to-day as their premise, a launchpad for the remanufacture of identity. Grappling with the grubby means of producing one’s self is the true task:

“I no longer write poems,” Rodríguez Núñez tells Hedeen, “I write poetry. When I write, I’m not interested in the structure; it’s the process itself that’s most important. In other words, my strategy is precisely not to have a strategy, but to have a tactic.”

The mesmeric energy exists separate from the mere lack of capitalization and punctuation, though. It comes from the gyre of his attention. To borrow a description from one of his poems, his process is like “a centrifuge where molasses runs off”.

He also does not insist on his Cuba as a truth bestowed. In fact, “to forget is to create”. It is the inherent instability of a process lacking telos, the inversion of photographic aura. Rodríguez Núñez doesn’t aim to capture the real Havana, or the real soul of Cuba, or his own true self. When the ex-pat’s comfortable distance has collapsed, and the poet abroad suddenly comes face-to-face with the real, distance and intimacy are each transformed by perception and the productive process — authored, not authoritarian. -

“I no longer write poems,” Rodríguez Núñez tells Hedeen, “I write poetry. When I write, I’m not interested in the structure; it’s the process itself that’s most important. In other words, my strategy is precisely not to have a strategy, but to have a tactic.”

The mesmeric energy exists separate from the mere lack of capitalization and punctuation, though. It comes from the gyre of his attention. To borrow a description from one of his poems, his process is like “a centrifuge where molasses runs off”.

He also does not insist on his Cuba as a truth bestowed. In fact, “to forget is to create”. It is the inherent instability of a process lacking telos, the inversion of photographic aura. Rodríguez Núñez doesn’t aim to capture the real Havana, or the real soul of Cuba, or his own true self. When the ex-pat’s comfortable distance has collapsed, and the poet abroad suddenly comes face-to-face with the real, distance and intimacy are each transformed by perception and the productive process — authored, not authoritarian.

“I no longer write poems,” Rodríguez Núñez tells Hedeen, “I write poetry. When I write, I’m not interested in the structure; it’s the process itself that’s most important. In other words, my strategy is precisely not to have a strategy, but to have a tactic.”

The mesmeric energy exists separate from the mere lack of capitalization and punctuation, though. It comes from the gyre of his attention. To borrow a description from one of his poems, his process is like “a centrifuge where molasses runs off”.

He also does not insist on his Cuba as a truth bestowed. In fact, “to forget is to create”. It is the inherent instability of a process lacking telos, the inversion of photographic aura. Rodríguez Núñez doesn’t aim to capture the real Havana, or the real soul of Cuba, or his own true self. When the ex-pat’s comfortable distance has collapsed, and the poet abroad suddenly comes face-to-face with the real, distance and intimacy are each transformed by perception and the productive process — authored, not authoritarian. - Daniel E. Pritchard medium.com/anomalyblog/the-brilliance-of-the-cut-on-víctor-rodríguez-núñezs-tasks-c3e5f1db7171

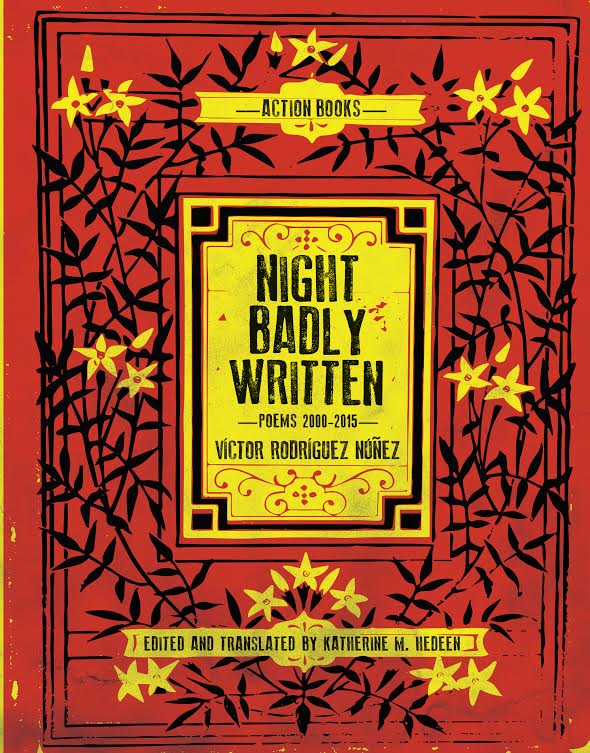

Victor Rodríguez Núñez, Night Badly Written: Poems 2000-2015, Trans. by Katherine M. Hedeen, Action Books, 2017.

"The imagination of this Cuban, this true poet...stains the darkness of these times with a red squirrel guided by the light...Victor Rodriguez Nunez doesn't wait for the arrival of anyone because he was baptized by poetry at birth."--Juan Gelman

"Victor Rodriguez Nunez is a unique poet, not comparable to anyone writing today in any language I can read. [...] Immense is his power of inheritance, the fierceness of his autonomy, compassion and instinct to broaden the livable space. Nobody else has such a gift to encompass so many crossroads, to be at the heights Vallejo once was, but so free and singular. Nobody else can be gracious, quotidian, marvelously strange and a winner of history at the same time. With branches and roots still expanding."--Tomaž Salamun

"This collection by Victor Rodriguez Nunez lets the night speak in its revolutionary strangeness, 'withstand[ing] / the advance of clarity' and established order. I know of no poet who gives us such vital access to 'the crowded inner landscape' and puts us into such intimate relationship to its numinous mysteries. This visionary poetry is fearless, fierce, and dazzling."--Mary Szybist

Victor Rodríguez Núñez, Every Good Heart is a Telescope, Trans. by Katherine M. Hedeen, Toad Press, 2013.

Poetry always has the feel of mysticism and mystery, or maybe this feeling is a stereotype left over from high school literature class. It is generally the result of confusion, lack of time committed to consuming the poetry, and the general difficulty poetry imposes on the reader.

In Víctor Rodríguez Núñez’s collection, Every Good Heart is a Telescope, he elevates the mysticism and mystery of poetry through people, events, and experiences that we can be begin to understand tangibly through the use of metaphors relating to science, mathematics, inventorship, and space phenomena. Such imagery is equally as mystical and mysterious as poetry itself, but almost everyone has been consumed by science, mathematics, inventorship, or space at some point in their lives, most often during childhood. The reader will immediately become refamiliarized with their dreams of the yesteryear through Núñez’s love affair with the heavens, metaphysics, alchemy, and our unbounded universe.

As an example, my favorite in the collection is a poem entitled Hypothesis, describing admiration through great mathematicians and scientists, including the likes of Ptolemy, Copernicus, Bruno, Galileo, Kant, and Hegel:

Ptolemy thought

the world was like certain women’s eyes

A sphere of wet crystal

where each star traces a perfect orbit

with no passion

tide or catastrophe

Copernicus came along

wise man who traded breasts for doves

cosines for fright

and the sun’s pupil became the center of the universe

while Giordano Bruno crackled

to the delight of husbands and priests

Then Galileo

probing deeply into young girls’ hearts

shipwrecked on good wine

—light gathered up by sun—

he raped stars that weren’t from the movies

and before dying on a comet’s tail

he declared love to be infinite

Kant in turn knew nothing of women

prisoner in a butterfly of calculations

in metaphysical pollen

and for Hegel

so abstract

the problem was excessively absolute

As for meEach of Núñez’s poems has similar patterns to that reflected above; they are each fleeting at first glance, but upon a second, third, fourth read, they are universal and infinite in reach. This is partly due to his reliance on images pulled from science, mathematics, philosophy, and metaphysics, each of which have the same unbounded aura. This is also a result of Núñez’s continual practice of directly addressing the reader in his poems. This technique causes each poem to become intimate in a way that I have rarely encountered in poetry.

I propose to the twentieth century

a simple hypothesis

critics will call romantic

Oh young girl who reads this poem

the world revolves around you

In Vincent Francone’s Three Percent review of Of Flies and Monkeys, Francone states “a poet needs to involve me in the process of reading the poem, in short: craft is not enough.” Núñez meets and surpasses Fracone’s requirement—he does not use his craft as a crutch, and instead supplements his skill by requiring the reader to be alert, to become engrossed, and most importantly, not to forget the collection after only reading it once. My sole criticism of the volume is that I wish the original Spanish text were included alongside the English translation. Despite this, I will never look at the stars again without thinking of Núñez’s poetry. - Tiffany Nichols

Víctor Rodríguez Núñez (Havana, 1955) is one of Cuba’s most noteworthy contemporary writers. He is a poet, journalist, literary critic, translator, and scholar. Among his books are Cayama (1979), Con raro olor a mundo (1981), Noticiario del solo (1987), Cuarto de desahogo (1993), Los poemas de nadie y otros poemas (1994), El último a la feria (1995), Oración inconclusa (2000), Actas de medianoche I (2006), Actas de medianoche II (2007), tareas (2011) and reversos (2011). His Selected Poems has come out in many countries, most recently Todo buen corazón es un prismático (2010) in Mexico, and has been translated into English, French, Italian, and Swedish. In addition, a wide selection of his poems has appeared in another twelve languages. His poetry has been awarded major prizes, such as the David (Cuba, 1980), the Plural (Mexico, 1983), the EDUCA (Costa Rica, 1995), the Renacimiento (Spain, 2000), the Leonor (Spain, 2006), and the Rincón de la Victoria (Spain, 2010). During the eighties he wrote for and was the editor of El Caimán Barbudo, one of Cuba’s leading cultural magazines. He has compiled three anthologies that have defined his poetic generation and published various essays on Spanish American poets. Among his translations are books by John Kinsella, Margaret Randall, and Mark Strand. He divides his time between Gambier, Ohio, where he is Professor of Spanish at Kenyon College, and Havana, Cuba.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.