Sam Mills, The Quiddity of Will Self, Corsair, 2012.

The ghost of a beautiful young woman, Sylvie, hovers outside the window of Will Self's study. She is seeking to influence his latest novel, before she can rest in peace. Sylvie was a member of the WSC - a mysterious cult of charismatic writers who appear to worship Will Self. When Richard, a twenty-something idler and literary wannabe, discovers Sylvie's dead body he gets sucked into their dark world of absinthe, cloaks and bizarre initiation rites, slowly losing his sense of perspective on the strange events that encircle him. What is the true nature of the WSC? What did they do to Sylvie? And does Richard now face a similar fate?

“If you love books. If you love books so much that you love even the word ‘book’. Then this is a book you’ll love.” Jonathan Trigell

"Funny, inventive. . . Mills keeps the game up with the sheer unexpectedness of her narrative. . . an ingenious, energetic read, admirable for the verve and macabre imagination with which Mills pursues her quarry." The Sunday Times

“An extraordinary odyssey of orgiastic obsession… a novel as ambitious and outrageous as this seems to defy conventional review… the author's invention and enthusiasm – and the depth of her apparent obsession – are undoubtedly infectious.” - The Guardian

“An inventive debut novel about a group of literary wannabes who long to influence Will Self. A literary equivalent of Being John Malkovich, it sparkles with knowing wit and almost limitless literary time travel....An extraordinary feat of the imagination” - Alex Hemingsley's Book Choice BBC Radio 2 Claudia Winkleman’s Arts Show

"It sounds too weird to be enjoyable, but the themes -- the extent to which art mirrors life and vice versa and whether the writers who teach us about life are worthy of worship -- are well drawn out. And for the unconverted (I wouldn't say knowledge of Self's work is a pre-requisite for reading this) the cultish depths of Mills' affection for the author is genuinely infectious... quirky above and beyond the call of duty" - Irish Independent

"If you enjoy a book that makes you reconsider the paradigms of fiction, the oddity of imagination and the brilliance of original thought, look no further than author Sam Mills’ debut adult work The Quiddity Of Will Self. Within the pages of The Quiddity Of Will Self lies a true gem of contemporary literature. It encompasses so many elements of the very best writing, from the transgressive to the absurd, suspenseful to the comedic. This is a must for any reader who craves to be challenged by a novel, and will in turn find themselves infinitely rewarded. Like finding a fifty-dollar note in your back pocket on a hungover Sunday morning, The Quiddity Of Will Self is a wonderful, ambitious and surprising novel. A breath of fresh air sure to be one of the most talked about books of 2012 and absolute must for any book club looking to add some spice into their reading by embracing the weird, and finding the wonderful." Andrew Cattanach, Booktopia

“A fine book, nine years in gestation and publishing, it should find a space on the cult shelf of any good bookshop.” - New Books Magazine

"The Quiddity of Will Self is perhaps flawed, but it’s also a great and very ambitious book, and it needs to be accepted for what it is. You can enjoy the ideas, the invention, and the constant confusion of fact, fiction and authorship..." - Giles Anderson

“Of course, there’s much more to Self than just a predilection for deploying arcane vocabulary, and as such Mills has more to draw on than wordplay. The novel is divided into five parts, of which the section narrated by Richard is the first. The next two parts are macabre and original enough that they might sit comfortably alongside any of the stories in Self’s dark collections Dr Mukti and Other Tales of Woe, and Liver...a playful novel” Pop Matters website review by Alan Ashton-Smith

'The somewhat embarrassing ramblings of S Mills' Private Eye

“The story is strong and some particularly creative concepts make for a good read reminiscent of The Secret History.” - Sarah Gammon

“Skilled, confident and brave; Sam Mills writes in worship of an existing cult author... Identity, insanity, orgies, mystery, murder, loss, deception, ghosts, hermaphroditism - it’s all in here and yet it doesn’t feel overcrowded as a novel. Its denseness works and the creative ideas drive the story well. This is literature of grand proportions and I’m not surprised it is the work of nine years... ‘The Quiddity of Will Self’ isn’t a book to devour in one sitting (I fear it may explode your mind), it is a book to take your time with, to break from, ponder and digest its ideas.” Book blogger Tessa Brechin

"So if you’re looking for something to get your teeth into, or a book to push you out of your comfort zone, give this dark and refreshingly different tale a try." - Book blogger Literary Kitty

"TQOWS is a novel I found myself flying through, a real page turner, which is quite a feat for a book that boasts such beautiful, challenging prose, but the essence of the tale was so beguiling, just as the essence of Self's genius is in the book, that I was unable to put it down. The Quiddity of Will Self is, in my opinion, an excellent book, tremendously written and beautifully measured, a must for fans of a myriad of genres, and Sam Mills is a name to look out for..." - Book blogger One Man Book

"A particularly original, quirky, imaginative and extremely funny book” - Book blogger Chris Haak

“Obsessional, fragmentary, metafictional and strangely beguiling” – Lee Rourke

A former girlfriend lived in a house previously inhabited by Will Self and his first wife. Spending the night in what I presumed to have once been the master bedroom (the house was now shared, rooms individually assigned), I wondered if I could detect a faint ghostly presence. Indeed, I wrote about it in a short story – "The rancid smell of ancient couplings occasionally wakes her in the night" – which I sent to Self. But the satirist – an acquaintance, even a friend, of mine – was not amused, opining, if I remember rightly, that it was in poor taste and he hoped I wasn't intending to publish it. So, imagine my surprise as I plunged deeper and deeper into Sam Mills's extraordinary odyssey of orgiastic obsession to encounter lines such as "My cock soared Selfwards", "Her left hand, splayed across the final pages of Great Apes, pressed it against her stratified pinkness … her climax shuddering up, up, up to Will …" and "I sweep into his cock, feel myself fly as it rears up like a rollercoaster." The cock, it almost goes without saying, is Self's.

A novel as ambitious and outrageous as Mills's fourth (her first emphatically for adult readers) seems to defy conventional review and synopsis, so freely does it play with notions of authorship and fiction versus reality, even to the extent of the author having inaugurated the very same Will Self Club (WSC) around which she spins her increasingly absurd yarn.

In a plush block of flats in north London, Richard Smith discovers the body of his neighbour Sylvie, who, it seems, has been having plastic surgery in an effort to look more like Will Self, a figure of worship for Sylvie and the members of the WSC, who include objectionable but charismatic young writer Jamie Curren and his equally unappealing acolytes. Finding himself initially under suspicion, Richard turns private dick and infiltrates the WSC, getting to know Jamie, his half-sister Zara, author of multicutural love story Bombay Mix, fake misery memoirist the tweedy Tobias, and other cartoonish but strangely believable literary types.

The action takes place in a series of galleries, derelict mansions and Soho clubs that readers of Self's work will recognise from The Sweet Smell of Psychosis and elsewhere. Self's characters pop up, too, from Dr Busner to the Fat Controller. Extracts are quoted, including a lengthy one from The Book of Dave in part two of the novel, in which Sylvie haunts Self's writing room, with its typewriter, fold-up bike and yellow Post-it notes stuck to the walls. There's even a Professor Self – "no relation" – in the weaker part three, a diary kept by Richard during his incarceration in a Liverpool tower block as part of a government initiative, the New Deal Reintegration Scheme (Richard reimagines it as a live art event in which the public may come to watch him write his novel, The Diary of a Murderer).

Part four (there is a contents page; these are not plot spoilers) propels us forwards to 2049, where we learn that Self died in 2045, having finally won the Booker at the age of 82. But it's part five, "Sam Mills", I was most looking forward to, since self-referential fiction is definitely my idea of fun. I won't spoil yours by revealing any details of the author's transmogrification.

If the fictionalised Mills's claims are to be believed, the novel took her nine years to write. A labour of love, clearly, and Self is the object of a great deal of it. It will be interesting to see if the example of Paul Auster and Sophie Calle has set a precedent (he fictionalises her in Leviathan, she adopts his fictionalisation in her life and her art), and Self writes a novel called Drug Lime that eventually wins him the Booker. The Quiddity of Will Self felt overlong, as most contemporary novels do, and a squeezed middle would have been to its benefit, not to mention a more thorough copy-edit, but the author's invention and enthusiasm – and the depth of her apparent obsession – are undoubtedly infectious. - Nicholas Royle https://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/mar/30/quiddity-will-self-sam-mills-review

It's easy to understand someone nurturing a secret fandom of Will Self.

His fantastically craggy face, richly ornate vocabulary and wryly sensible Newsnight contributions have put him up there with the likes of Germaine Greer and Stephen Fry as Britain's most telly-friendly intellectual. He's also a quite brilliant purveyor of epoch-shaping fiction, who has embraced chronic laziness -- or "idling" as he calls it -- as a lifestyle choice. There really is a lot to love. Still, it's hard to imagine that there would be enough people out there to form a Will Self fan club and that the president of said club could write a novel (largely about Will Self) and that it would be any good. And yet, The Quiddity Of Will Self, by Sam Mills, though slightly overlong, is mostly enjoyable.

Part love story, part murder mystery, part meditation on the state we're in, the book is a kind of literary Being John Malkovich, with Self taking the place of the actor. It follows Richard Smith, a young wannabe writer pissing away his life after coming into some inheritance money. He discovers the corpse of the murdered Will Self, except that, rather than actually being Self himself, it is, in fact, a transsexual who was surgically altered to look like the celebrated writer, whom she idolised. It only gets more absurd from there on in.

Finding himself under suspicion, Smith tries to infiltrate the fan club, in the process getting to know some over-the-top literary types who plunge him into a dark world of orgies, alcohol and board games.

Finding himself under suspicion, Smith tries to infiltrate the fan club, in the process getting to know some over-the-top literary types who plunge him into a dark world of orgies, alcohol and board games.

Most of the action takes place against backdrops that readers of Self's novels will recognise -- eerily deserted galleries, derelict mansions, louche Soho clubs -- and the book is seasoned to choking point with plot and character references to Self's work. Lengthy extracts are also quoted, (unnecessarily, it feels) and some of the scenes in the book seem a little self-consciously designed to shock.

Along the way there are there are demented psychiatrists, macabre literary cults and a strange interlude with a talking kitchen.

Along the way there are there are demented psychiatrists, macabre literary cults and a strange interlude with a talking kitchen.

It sounds too weird to be enjoyable, but the themes -- the extent to which art mirrors life and vice versa and whether the writers who teach us about life are worthy of worship -- are well drawn out. And for the unconverted (I wouldn't say knowledge of Self's work is a pre-requisite for reading this) the cultish depths of Mills' affection for the author is genuinely infectious. It all feels slightly tongue in cheek as well, which adds to its literary curiosity value, while detracting from any lasting emotional power.

Part Five, a piece of self- referential fiction simply entitled Sam Mills, is hilarious and sees the author wondering how she will sell her unmarketable opus.

Part Five, a piece of self- referential fiction simply entitled Sam Mills, is hilarious and sees the author wondering how she will sell her unmarketable opus.

Will Self himself offered his "suspicious support" to the project. He may be pleased to learn The Quiddity Of Will Self predicts him winning the Booker in his 80s.

The book itself is unlikely to garner such adulation, but it does provide brief moments of genius and is quirky above and beyond the call of duty. - DONAL LYNCH https://www.independent.ie/entertainment/books/review-the-quiddity-of-will-self-by-sam-mills-26853390.html

I need to start with a disclaimer: there are a lot of Dicks in this book. There are also lots of long and often obscure words. But while I’m keeping the dicks in my review to a minimum, the words are harder to translate. In fact, you may find them a bit of a mouthful, but you only have your Self to blame. So if you read this and get your haecceity confused with your quiddity, as I’ll do in a bit, don’t worry. I’m just easing you into some of the language of the novel. It’s all part of the fun—and after all, isn’t it Will Self’s own stated aim “to be misunderstood”?

Like many of you, I’ve wondered Whatever Happened to Corey Haim, gone Desperately Seeking Julio (the available translation of Maruja Torres’ Oh es él! Viaje fantástico hacia Julio Iglesias, though you would be mad not to prefer the more literal Oh it’s him! Fantastic voyage to Julio Inglesias) and thought about Being John Malkovich.

The Quiddity of Will Self, according to its author Sam Mills, is the “literary equivalent” of Malkovich—or BJM, as it’s called in the novel. At first, I had difficulty with this concept. After all, one of the main reasons the film works is that Malkovich is in it. He’s there on the screen in front of you, quite literally being John Malkovich. How do you replicate that in literature? You can take an author (as Mills has), you can write like them (as Mills sometimes does), you can put them into your novel as a character (as Mills has), but you can’t ever really be them. Short of Self writing about himself, as he’s already done in Walking to Hollywood, the same idea doesn’t easily translate from screen to page.

The other difficulty I had is that quiddity, the concept central to Mills’ novel, is all about a thing’s “whatness”. Not what makes it unique, which is haecceity or “thisness”, but what properties it shares with others. Often, though, Mills’ fictional quiddity seems more like haecceity. Her book is written in the style of the idea of Will Self: long words and lots of cocks. Characters in The Quiddity of Will Self form a cult to worship the Self, and there is even a drug that allows them to share perspective as the Self. Substance abuse theory aside, if I wanted to get at the whatness or thisness of Will Self, why not just read his books instead?

Which is harsh. The Quiddity of Will Self is perhaps flawed, but it’s also a great and very ambitious book, and it needs to be accepted for what it is. You can enjoy the ideas, the invention, and the constant confusion of fact, fiction and authorship—one reviewer got the author’s gender wrong, not so strange when you consider that the fictional version of Sam Mills is male in part five of the novel—but if you’re looking for a sympathetic narrator, you’re unlikely to find one here.

The book is divided into five sections of varying style, quality and length. Despite having one of my favourite opening lines ever, the first section of the book is much too long. It has more than a whiff of Self’s novella, The Sweet Smell of Psychosis, in which a journalist called Richard falls into the orbit of media monster Bell and his cronies. In Quiddity’s first part, a writer (another Dick) falls in with the inner literary circle of the Will Self Club after his mixed-up downstairs neighbour, who has had plastic surgery so that she resembles Will Self, is found murdered. The victim, Sylvie, returns in part two, this time as a ghost who haunts Self’s study whilst the writer works obliviously. Part three continues the tale of Richard, who has been framed for Sylvie’s murder, as he participates in a New Deal Reintegration program run by Professor Self (no relation) as an alternative to prison, and part four is set in a 2049 where Will Self has finally won the Booker Prize, aged 82.

However, it is part five where the book comes into its own. We are introduced to the narrator Sam Mills, as he (yes, he) tries to get The Quiddity of Will Self published, fails to meet Will Self, and founds the Will Self Club. There’s quite a lot of BJM too. This witty, semi self-referential section really works, and made me forgive some of the weaker parts of the novel as they’re necessary as precursors for this last and strongest section. According to both the fictional Sam Mills in the book and the author in an interview, The Quiddity of Will Self took nine years to write. As a novel it’s perhaps too long and disjointed, but as a set of linked stories (much like Self’s debut The Quantity Theory of Insanity) it stands up, and the final section flies. It is weakest where it feels like the author has written part of it, put it down, and then returned quite a while later with a new idea, but that’s a small price to pay because the ideas themselves are worth it.

As Sam’s fictional agent Archie tells him (with a nod to her real agent, Simon Trewin), “We’re in a recession and everyone is cautious.” Fortunately, though, they weren’t too cautious to publish this strange and original book. Whatever its shortcomings, it remains very much my idea of fun. - Giles Anderson https://www.litro.co.uk/2013/01/the-quiddity-of-will-self-by-sam-mills/

The book itself is unlikely to garner such adulation, but it does provide brief moments of genius and is quirky above and beyond the call of duty. - DONAL LYNCH https://www.independent.ie/entertainment/books/review-the-quiddity-of-will-self-by-sam-mills-26853390.html

I need to start with a disclaimer: there are a lot of Dicks in this book. There are also lots of long and often obscure words. But while I’m keeping the dicks in my review to a minimum, the words are harder to translate. In fact, you may find them a bit of a mouthful, but you only have your Self to blame. So if you read this and get your haecceity confused with your quiddity, as I’ll do in a bit, don’t worry. I’m just easing you into some of the language of the novel. It’s all part of the fun—and after all, isn’t it Will Self’s own stated aim “to be misunderstood”?

Like many of you, I’ve wondered Whatever Happened to Corey Haim, gone Desperately Seeking Julio (the available translation of Maruja Torres’ Oh es él! Viaje fantástico hacia Julio Iglesias, though you would be mad not to prefer the more literal Oh it’s him! Fantastic voyage to Julio Inglesias) and thought about Being John Malkovich.

The Quiddity of Will Self, according to its author Sam Mills, is the “literary equivalent” of Malkovich—or BJM, as it’s called in the novel. At first, I had difficulty with this concept. After all, one of the main reasons the film works is that Malkovich is in it. He’s there on the screen in front of you, quite literally being John Malkovich. How do you replicate that in literature? You can take an author (as Mills has), you can write like them (as Mills sometimes does), you can put them into your novel as a character (as Mills has), but you can’t ever really be them. Short of Self writing about himself, as he’s already done in Walking to Hollywood, the same idea doesn’t easily translate from screen to page.

The other difficulty I had is that quiddity, the concept central to Mills’ novel, is all about a thing’s “whatness”. Not what makes it unique, which is haecceity or “thisness”, but what properties it shares with others. Often, though, Mills’ fictional quiddity seems more like haecceity. Her book is written in the style of the idea of Will Self: long words and lots of cocks. Characters in The Quiddity of Will Self form a cult to worship the Self, and there is even a drug that allows them to share perspective as the Self. Substance abuse theory aside, if I wanted to get at the whatness or thisness of Will Self, why not just read his books instead?

Which is harsh. The Quiddity of Will Self is perhaps flawed, but it’s also a great and very ambitious book, and it needs to be accepted for what it is. You can enjoy the ideas, the invention, and the constant confusion of fact, fiction and authorship—one reviewer got the author’s gender wrong, not so strange when you consider that the fictional version of Sam Mills is male in part five of the novel—but if you’re looking for a sympathetic narrator, you’re unlikely to find one here.

The book is divided into five sections of varying style, quality and length. Despite having one of my favourite opening lines ever, the first section of the book is much too long. It has more than a whiff of Self’s novella, The Sweet Smell of Psychosis, in which a journalist called Richard falls into the orbit of media monster Bell and his cronies. In Quiddity’s first part, a writer (another Dick) falls in with the inner literary circle of the Will Self Club after his mixed-up downstairs neighbour, who has had plastic surgery so that she resembles Will Self, is found murdered. The victim, Sylvie, returns in part two, this time as a ghost who haunts Self’s study whilst the writer works obliviously. Part three continues the tale of Richard, who has been framed for Sylvie’s murder, as he participates in a New Deal Reintegration program run by Professor Self (no relation) as an alternative to prison, and part four is set in a 2049 where Will Self has finally won the Booker Prize, aged 82.

However, it is part five where the book comes into its own. We are introduced to the narrator Sam Mills, as he (yes, he) tries to get The Quiddity of Will Self published, fails to meet Will Self, and founds the Will Self Club. There’s quite a lot of BJM too. This witty, semi self-referential section really works, and made me forgive some of the weaker parts of the novel as they’re necessary as precursors for this last and strongest section. According to both the fictional Sam Mills in the book and the author in an interview, The Quiddity of Will Self took nine years to write. As a novel it’s perhaps too long and disjointed, but as a set of linked stories (much like Self’s debut The Quantity Theory of Insanity) it stands up, and the final section flies. It is weakest where it feels like the author has written part of it, put it down, and then returned quite a while later with a new idea, but that’s a small price to pay because the ideas themselves are worth it.

As Sam’s fictional agent Archie tells him (with a nod to her real agent, Simon Trewin), “We’re in a recession and everyone is cautious.” Fortunately, though, they weren’t too cautious to publish this strange and original book. Whatever its shortcomings, it remains very much my idea of fun. - Giles Anderson https://www.litro.co.uk/2013/01/the-quiddity-of-will-self-by-sam-mills/

The Will Self Club

For information and news updates about the Will Self Club, please visit www.thewillselfclub.co.uk. Below is an outline of the Philosophy of the WSC:

"We have no true spiritual masters in current Western society - our priests are paedophiles, our politicians are celebrities, our celebrities are earthworms. Who can fill this spiritual vacuum? In the past, we might have turned to philosophers, but they have gone out of fashion and even Alain de Botton will not suffice. The answer can only lie with writers. Fiction can illustrate greater truths than non-fiction; the enduring appeal of 1984 tells us more about the dangers of an authoritarian society than any history textbook. A writer stands outside society, observing, analysing, searching for the truth. Their faith is a watermark in the pages of their books; C.S.Lewis spread out his Narnian imagination over the skeleton of his Christian faith and Swift operated within a matrix of Judeo-Christian principles. A writer can teach us about life, morals and how to construct a better sentence. Hence, the greatest writers are worthy of worship.

This is an idea that originated with the Golden Dawn and grew in the early twentieth century with the Edgar Allan Poe Faith, a shadowy group who included Jack the Ripper as one of their initiates, leading to fatal consequences. Since then, there has been a widespread growth in literary religion - or 'Writer Worship Clubs' (as the Guardian has termed them), or 'Satantic Book Boffins' (The Daily Mail). Currently, their popularity is at its peak. In Sussex, a Virginia Woolf Club has been established, though it seemed not so much a religion as a thinly veiled forum for transvestites to enjoy putting on grey wigs and 30s-style dresses whilst sleeping in the grounds of her former domain, Monk's House in Rodmell. In Glasgow, rather inevitably, the Irvine Welsh Club now enjoys 200 members, whereby the Initiation Ceremony depends upon those who can negotiate the best bargain for crack cocaine from a selected drug dealer. In Wessex, construction is shortly to be completed on a temple dedicated to Thomas Hardy and the Tom Paulin Dublin Faith has now been recognised as a world religion, though it is listed in the Directory of Religions just beneath Jedi Warriors, suggesting it has yet to be accepted as a serious faith.

Of these Faiths, the Will Self Club (officially known as the W.S.C) is considered to be the elite superior (though the Martin Amis School lags behind as a close second). Membership is said to be a mysterious and, at times, torturous process. There is the black ball system, followed by a complex initiation. The member is never 'told' that they have been accepted into the faith, only 'shown'. The monthly worship sessions are said to take place in a stately home on the outskirts of London; a journalist who once attempted to infiltrate one such meeting was never seen again. All that remains of his visit are some texts, abstract in nature, such as 'absinthe', 'torn pages and naked breasts' and 'I'll never win the Nonce Prize'. Those who do manage to infiltrate the hierarchies of this faith, however, receive the lifelong blessing of W.S. in deified form, frequent moments of exquisite serendipity, and experiences of the flesh that are miraculous and ecstatic in sensation."

© Sam Mills | created at www.mrsite.com

Sam Mills, Blackout, Faber And Faber, 2010.

I am on the run. The police are chasing me because they think I'm a terrorist.The trouble all began when my Dad, who's a bookseller, hid a writer called Omar Shakir in our house. Omar wrote a book you may have heard of but won't have read. It's called The Exploded. It inspired a terrorist attack on London. That's why it's a BANNED book. We live in dangerous times. Lots of books are banned now. Harry Potter. Alex Rider. James Bond. If you're caught reading one, you could go to jail. The state says books and films and computer games have to be nice and happy, so they don't inspire teenagers to commit violent crime or terrorism. I thought they were wrong. I thought, how much harm can a book do?Then I read one. Now I'm about to commit murder. Now I know better.BOOKS ARE DANGEROUS.

It's an odd thought about Sam Mill's Blackout, which deals with censorship, but her book would itself have been at risk of being banned in South Africa in the 1960s merely because of its title.

In 1965, a censor during the Apartheid era, without troubling to actually read the book, put Anne Sewell's 1877 novel Black Beauty on a banned list because he didn't like the title. He wrongly assumed that a Victorian novel about a horse was in fact a black rights novel.

Banning books is not an issue that goes away. Joseph Heller's Catch 22 was banned in the 1970s by certain states in America and those theatre-goers who see a production of the Wild Swans at the Young Vic in 2012 may reflect on the fact that they are seeing a work of literature that is still banned in China.

So Sam Mills is taking on a meaty subject in her new novel Blackout (she thanks Philip Ardagh in the acknowledgements for "thinking up my title") but then her first two novels - A Nicer Way To Die and The Boys Who Saved The World - are both bold, challenging works.

Blackout is set in a near future Britain where, because of the threat of social disorder and terrorism, books are banned or 'ReWritten' in sanitised formats. Even Harry Potter (by supposedly encouraging children to try magic) is deemed dangerous enough to be banned. The spirit of Orwell hangs over Mills's book. CCTV cameras are everywhere. It's a time of public hangings, an era when books and iPods are burned and confiscated. Some terrorists and transgressors are even stoned to death in public. - Martin Chilton http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/children_sbookreviews/8889808/Blackout-by-Sam-Mills-review.html

Black Out is set in England in the near future. Books have been deemed dangerous by the State as they seem to be causing kids to commit terrorist acts.

Terrorism is the major issue at this time.The State says books have to be sweet and pleasant so they don't inspire teenagers to commit crime. Famous novels are rewritten, many are banned.

Read and banned book and you go to jail.

Stefan is the son of a bookseller. He goes to school and is baffled by the stuff they read, they don't make sense(especially when he's read bits of these books before the state rewrote them). But he has been brainwashed by the State into thinking books are evil and that it's perfectly acceptable to hold public executions of authors in the name of the war on terror.

But then he comes home one day to find a "terrorist" in his home. Omar Shakir. Sentenced to death just for writing a book with supposedly illegal content. He is in hiding, His dad is helping them.

But that's wrong, truth to the state will set you free. At least that is the poor conclusion Stefan's indoctrinated brain comes up with. So when the Censorship pays them a visit Stefan turns them all in.

Taken to The Institution, Stefan is interrogated,some might say tortured, before being sent to live with a new family, Mr and Mrs Kelp. But they have their own plans. They are government rewriters and use him to study the effects of books that are banned.

Then Omar rescues him, but neither know he's been brain washed to kill the Words members when a trigger phrase is spoken, until it's too late. Hated both by the State for shooting someone in public and hated by the words for killing there members Stefan is on his own.

A when he stumbles across a secret code in a book will he decipher it in time to save his father?

Read this book to find out how Stefan struggles with conflicting thoughts and a country that wants to keep children down,

This is a great book for teenagers and upwards, it's told in an interesting story but raises some interesting points about government control and dictatorships, as well as fighting back etc. Also the idea books can control you is an interesting one. it's a very interesting read for that aspect and the story is pretty good as well.

I'd recommend buying it just to try. - Devonian reviewer

Black Out is set in England in the near future. Books have been deemed dangerous by the State as they seem to be causing kids to commit terrorist acts.

Terrorism is the major issue at this time.The State says books have to be sweet and pleasant so they don't inspire teenagers to commit crime. Famous novels are rewritten, many are banned.

Read and banned book and you go to jail.

Stefan is the son of a bookseller. He goes to school and is baffled by the stuff they read, they don't make sense(especially when he's read bits of these books before the state rewrote them). But he has been brainwashed by the State into thinking books are evil and that it's perfectly acceptable to hold public executions of authors in the name of the war on terror.

But then he comes home one day to find a "terrorist" in his home. Omar Shakir. Sentenced to death just for writing a book with supposedly illegal content. He is in hiding, His dad is helping them.

But that's wrong, truth to the state will set you free. At least that is the poor conclusion Stefan's indoctrinated brain comes up with. So when the Censorship pays them a visit Stefan turns them all in.

Taken to The Institution, Stefan is interrogated,some might say tortured, before being sent to live with a new family, Mr and Mrs Kelp. But they have their own plans. They are government rewriters and use him to study the effects of books that are banned.

Then Omar rescues him, but neither know he's been brain washed to kill the Words members when a trigger phrase is spoken, until it's too late. Hated both by the State for shooting someone in public and hated by the words for killing there members Stefan is on his own.

A when he stumbles across a secret code in a book will he decipher it in time to save his father?

Read this book to find out how Stefan struggles with conflicting thoughts and a country that wants to keep children down,

This is a great book for teenagers and upwards, it's told in an interesting story but raises some interesting points about government control and dictatorships, as well as fighting back etc. Also the idea books can control you is an interesting one. it's a very interesting read for that aspect and the story is pretty good as well.

I'd recommend buying it just to try. - Devonian reviewer

I have a lot of difficulty with dystopian books, which is why you’ll find I review them very rarely. At their worst for me, they tend to slide into one, a sort of malleable ‘future’s bad but X can sort it out’ plot which barely shifts from text to text. It’s rare to find ones which get that but – make it their own, you know? That make this future, this hideously real future actually – real. Too real. Like, blink and it’s here real.

Ladies and gentleman, I give you Blackout by Sam Mills. I came to this a bit blindly really, picking it up off the libray shelves by happenstance, and it was a little bit of a blank canvas. I didn’t know the author, I didn’t know the book.

Well, I do now. Mills has given us a scarily plausible future where books are rewritten, where reading banned books is a crime, and Stefan, the son of a bookshop owner, has just discovered that his Dad is hiding the author of one of the ‘worst’ in his house. It reads like a YA spin on 1984, with elements of Children of Men thrown in there for the mix, and it is a proper good book.

It’s also one that’s difficult to precis, in that the plot twists and folds upon itself, but if you know the references above, you’ve got a good idea of where this is going. Blackout also has some very skillful moments where the actual ‘danger’ of reading is discussed and the potential of a book to change the world – for good or for bad. There’s a lot here that could be used in a classroom context or in a discussion of banning books.

What I love in Mills’ prose is the way this all seems so, scarily, possible. This is skill, to make the horrific believable and actual. Though there are parts of this which sag, just a little, Blackout is a really really good book. - https://didyoueverstoptothink.wordpress.com/2013/11/23/blackout-sam-mills/

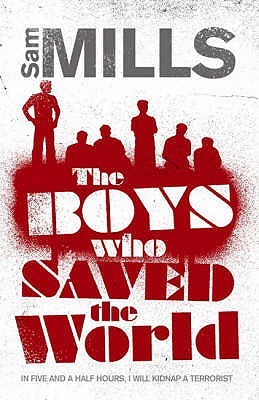

Sam Mills, The Boys Who Saved the World, FABER AND FABER, 2007.

Jon knows what he has to do. If he isn't strong, everyone in his school is going to die. Or so he's been told by Jeremiah, the leader of a group of lonely, damaged boys who have started a new religion. But when the boys become convinced that a classmate is involved in a plot to blow up the school, they lay their own plans.

INTERVIEW WITH THE AUTHOR

Sam Mills, A Nicer Way to Die, FABER AND FABER, 2006.

16-year-old James and his step-brother Henry are the only survivors in a horrific coach crash that kills their entire class. And James knows the nightmare has only just begun. For Henry hates James, bullies him in secret and has promised to kill him one day.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.