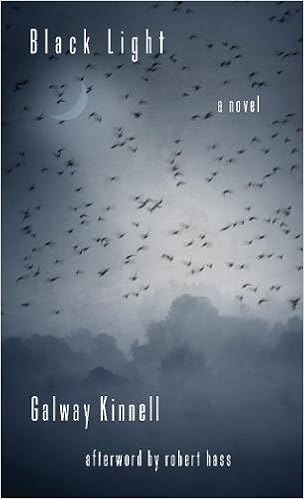

Galway Kinnell, Black Light: A Novel, Counterpoint; Revised ed., 2015. [1966.]

read it at Google Books

www.galwaykinnell.com/

Black Light is a voyage of discovery and transformation. Set in Iran, it tells the story of Jamshid, a quiet simple carpet mender, who one day suddenly commits a murder and is forced to flee. With this violent act his old life ends and a strange new existence begins.

Galway Kinnell combines his gift for precise imagery with a storyteller’s skill in this journey across the Iranian desert—away from the fragile self-righteous virtues of adopted moral tradition, into the disorder and sexual confusion of agonizing self-knowledge. First published in 1966 by Houghton Mifflin, this extensively revised paperback edition of Black Light brings a distinguished novel back into print.

"The writing is condensed, austere and effective . . . “ –The Atlantic

"[Black Light] is poetic in its pared down language and precise sensuous imagery.” –Times Literary Supplement

"Black Light shows that more poets should write novels... Running throughout the short novel is a landscape that feels both unforgiving and comforting that is mitigated by a quick moving and devastating tale of man trying to find peace in any form it will present itself in."—Spectrum Culture

This is the story of Jamshid, the carpet-mender of Meshed, who was an upright man, and who murdered the Mullah who told him that his motherless daughter was a slut. The book tells of his reverse pilgrimage in search of sanctuary after that deed. He first tries to give himself up, but the policemen will not listen. By the time they have learned of his act, he has taken to the desert, where the old murderer Ali finds him and befriends him. They move toward Shiraz with Hassan the camel, but before they reach their goal, Ali is dead, his heart pierced by the same shears that killed the Mullah, although Jamshid is not to blame, and the camel too has succumbed. According to Ali's wishes, Jamshid tries to bear the body to his wife at Shiraz but is forced to leave it in a cave; when he brings news of Ali's death he finds love waiting, but the law still pursues him and he flees to Tehran, where a brothel becomes his refuge until a final horror drives him further... Poet Kinnell is merciless in his evocation of the stark, surreal desert with its Zoroastrian death middens and haunted ruins, noncommittal toward the pitiful men making their way across it. His Black Light casts no shadow; it burns with a hard flame that masks compassion. Limited. - Kirkus Reviews

In 1959, Galway Kinnell, an American poet from Providence, traveled to Tehran to teach as a Fulbright Scholar. He spent six months teaching and another six working as a journalist for an English-language newspaper where he wrote short articles on the culture of his new home. Though he spent only a year in Iran, the impression it made on him was deep and the beauty, the landscapes, peoples and customs shape his fable-inspired novel Black Light.

The novel opens with Jamshid, the main-protagonist who is more Raskolnikov than Meursault, steadily at work restoring the head of a bird of paradise in a rug. He is a seemingly patient, hardworking man though he has an air of religious superiority. But his pious nature is overcome when he stabs a religious leader, Mullah Torbati, over attempting to extort him over the chastity of his daughter. From this seemingly senseless murder the story spirals into a travel narrative with Jamshid attempting to atone for his sin by running.

He takes to the desert and there he finds a cast of sordid characters. In the desert, he meets Ali, a notorious murderer who falls victim to murder himself. After Ali’s death, he vows to return his body to his widow in Shiraz. In the city he first meets an old-man smoking opium at the tomb of Hafez. Finally, through the old man, he meets Ali’s widow. Soon Jamshid’s luck runs out and he must flee the town. He decides to return to home to finally confess to the murder. However, he finds himself in the redlight district of Tehran, what Kinnell call’s New City, and there he meets a young prostitute, Goli and her caretaker/pimp the old “hag” Effat.

The novel ends so unlike a fable, however. There seems to be no moralizing conclusion; only a final scene of Jamshid fleeing once again. In this way, Black Light–which Kinnell firmly announces as a fable in the 1980 afterword–takes a more modern, absurdist turn. The action of the story is seen not as a man trying to find redemption but a story of the impossibility of atonement in life. In fact, Kinnell more or less spells this out in an exchange between Effat and Jamshid in the closing pages: “‘Jamshid,’ she said at the foot of the stairs, ‘I’ve only learned one this in my life.” Jamshid turned. ‘It’s that nothing matters.’” So, after all this travel, this heartache and destruction we are left with this moral.

For a novel about a very religious society, sex seems to be a driving force in the work. The catalyst to the murder of Torbati is his daughter’s sex. In Shiraz, he has sex with Ali’s widow then in the morning decides he must repent and go back to Tehran. In the last chapters, he is literally surrounded by sex workers. And finally, as he mental state breaks down, he breaks out in a rash all over his crotch and inner-thighs. More and more in the novel Jamshid is confronted with his inability to control the sex of others and throughout he is constantly thinking of his daughter’s sex drives and desires. It is a subtle undercurrent of the book, but one that leaves the impression that this novel is more than just a sophomoric aping of Camus’ existential absurdism.

Finally, Black Light shows that more poets should write novels. Kinnell, who passed away in 2014, was an important force in American poetry and his command of imagery and his patience for describing the bleak Irian desert and rough streets is obvious. As Jamshid wanders Kinnell renders the beauty and desolation, the stark contrasts and the ever-present brightness of the sun and sand into beautiful prose. Running throughout the short novel is a landscape that feels both unforgiving and comforting that is mitigated by a quick moving and devastating tale of man trying to find peace in any form it will present itself in. - Nicodemus Nicoludis

http://spectrumculture.com/2016/01/24/black-light-by-galway-kinnell/

Like the mythological Persian king he's named after, Jamshid, the carpet repairer, restoring the burned rug fibers of the head of a bird of paradise when we meet him on his knees working, thinks he's better and more brilliant than everybody else. It's not pure diabolical arrogance per se, but pride the murky result of his unprocessed pain (his wife is recently deceased and his daughter, Leyla — unmarried and without a single suitor at the age of sixteen! — might as well be deceased) has made him bitter to the point of apostasy. As his faith fades, he comes dangerously close to losing everything, not unlike his unfaithful namesake from the Persian epic, Shahnameh:

Jamshid surveyed the world, and saw none there

Whose greatness or whose splendor could compare

With his: and he who had known God became

Ungrateful, proud, forgetful of God's name

Even before we meet Jamshid in Galway Kinnell's novella, we know from the opening line — "Jamshid kept sliding forward as he worked, so that the patch of sunlight would remain just ahead of him, lighting up the motion of his hands" — that light and what light signifies in Kinnell's context — heaven's wisdom, favor, and rewards — will probably elude Jamshid, yet remain close, all too visible, on the edge of his grasp, as if he were in Hell gazing at Paradise, imploring Abraham with outstretched arm for a drop of water. Black Light's opening serves as fitting foreshadowing for this fable riffing off the downslide of Persia's once omnipotent king, Jamshid. Jamshid, the poor but not so humble man of Meshen, Iran, only feels "a little ashamed that he had never made a pilgrimage to Mecca or for that matter to the Shrine of Fatima at Qum." On the precipice of his spiritual abyss, so far gone in his rage over his life that didn't turn out right, Jamshid internally snubs those journeying to Mecca, the Hajis, and can barely stomach their contemptuous, Afghani glances cast his way. As if they're so self-controlled, so holy, "getting married for the few weeks of their sojourn," in order to make easier the supposed "spiritual rigors" required in their once-in-a-lifetime quest. Their false piety makes Jamshid laugh. Maybe his last. For in an impulsive instant, in a furious fit of pent up pique upon hearing the news that his daughter's rumoured "indiscretions" have made her unfit for marriage — unfit unless Jamshid agrees to the local mullah's assistance in the delicate matter (a bribe veiled in the white robes of religious duty), Jamshid lashes out with all the force in him at Mullah Torbati. Suddenly, inexplicably, Jamshid's carpet shears that just moments before moved in mindless attendance upon a charred rug, trimming the kaleidoscopic plumage of a bird of paradise, now lie next to a sacred corpse, bloodied.

And so begins Jamshid's anti-pilgrimage whose terminus is destitution, whose life sentence might be despair. Roaming a hard desert road as far removed from Mecca as the crescent from the cross, haunts the frail figure of Jamshid through his nomad existence. His destination is nowhere. Transformed into a tramp like so many infidels before him, he seeks he knows not what, maybe an oasis, anyplace he can create some purpose out of killing more time. He meets Ali out in the endless sands somewhere, a grizzled old man who's traveled back and forth himself for decades on the run, or in circles, from one fringe settlement to another, selling trinkets from whatever weathered sacks his decrepit camel still manages to haul, in exchange for bare necessities. But the supplies and the shelter and the sex never last. Nor do Ali's and Jamshid's doomed partnership.

What is Jamshid to do with the constant eclipse that's become of his tortured past, his very life? How can he forget when his past bleeds darkness out of deep wounds into every successive step, and the steps he'll trudge tomorrow? How can he see where he's heading, or from what or whom he must flee; how will he ever chance upon potential refuge with his eyes smothered by black light? Is redemption even possible for a man as accursed as Jamshid, who "could always sense the blackness of vultures in the sky. Never visible ... a constant presence."? One may wonder, too, whatever became of Persia's ancient king, their legendary Jamshid?

Escape with Jamshid from the many consequences of his crime like some vicarious Persian Raskolnikov along for the camel ride, outpost to outpost, palm grove to palm grove, swathed in the paradox that is Black Light's luminescence. It's a reading experience at times reminiscent of what The Sheltering Sky invoked. Mystery. Meaning. Wondering. Why?

While Kinnell is better known as a poet (The Book of Nightmares) and translator (The Poems of François Villon), his rare digression into prose in Black Light is certainly one to savor and reflect upon repeatedly, like enjoying time and again the myriad gradations of illumination in a radiant poem. - Enrique Freeque

http://enriquefreequesreads.blogspot.hr/2012/09/black-light-novel-by-galway-kinnell.html

In 1959, the American poet Galway Kinnell won a Fulbright fellowship to live and teach for a year in Iran. Although he did not learn more than ‘500 or so words’ of Persian during his stay, he acknowledged the impact his fellowship year had on him, and set his only novel, Black Light (1966. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin), in Iran. In story and content, Black Light is almost certainly an imitation of Sadeq Hedayat’s The Blind Owl (1957. New York: John Calder), although the poet has no memory of reading Hedayat’s masterwork, and indeed maintains that he never read it at all. The history of American practices of translation assumes new significance when considering the products of Kinnell’s time in Iran. This essay focuses on Black Light and Kinnell’s ethnographic travel writing, which appeared under the title ‘Persian Journals’ in a series in the Tehran Journal magazine, arguing that each of these texts is a translation into an American idiom of the different encounters Kinnell was having with Iran. - Amy Motlagh

Galway Kinnell, Collected Poems, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017.

read it at Google Books

The definitive collection of poems from Pulitzer Prize winner, MacArthur Fellow, and National Book Award winner Galway Kinnell.

“It’s the poet’s job to figure out what’s happening within oneself, to figure out the connection between the self and the world, and to get it down in words that have a certain shape, that have a chance of lasting.” —Galway Kinnell

This long-awaited volume brings together for the first time the life’s work of a major American voice.

In a remarkable generation of poets, Galway Kinnell was an acknowledged, true master. From the book-length poem memorializing the grit, beauty, and swarming assertion of immigrant life along a lower Manhattan avenue, to searing poems of human conflict and war, to incandescent reflections on love, family, and the natural world—including "Blackberry Eating,” "St. Francis and the Sow," and “After Making Love We Hear Footsteps” — to the unflinchingly introspective poems of his later life, Kinnell’s work lastingly shaped the consciousness of his age.

Spanning 65 years of intense, inspired creativity, this volume, with its inclusion of previously uncollected poems, is the essential collection for old and new devotees of a “poet of the rarest ability... who can flesh out music, raise the spirits, and break the heart.” - Boston Globe

The Collected Poems of Galway Kinnell by Galway Kinnell is a collection of sixty-five years of writing. Kinnell, a Navy veteran, experienced Europe and the Middle East while serving. He was also involved in the civil rights movement. Kinnell was awarded the Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award for Selected Poems and he studied at Princeton and earned his Master’s degree from the University of Rochester.

The tome of the work is presented in several sections reflecting publications and time. His earlier work takes the form of more traditional poetry with sights and feelings of his ports of call in the navy, particularly France and India.

What storms have blown me, and from where,

What dreams have drowned, or half dead, here

…

Each year I lived I watched the fissure

Between what was and what I wished for

Widen, until there was nothing left

But the gulf of emptiness.

The traditional form is partly owed to his admiration of Walt Whitman. He then moves to more of a “Beat” type of poetry. His work seems influenced by the movement even though he was not an active participant. His work in the late 1960s and 1970s moves much more into nature poems:

On the tidal mud just before sunset,

dozens of starfishes

were creeping. It was

as though the mud were a sky

and enormous, imperfect stars

moved across it slowly

as the actual stars cross heaven

In the 1980s through the 2000s Kinnell finds himself writing as an experienced sage. He relies on his personal experience and knowledge to create his mature works. Here, the poems reflect on aging and the death of those who were close and the lives of his children. Kinnell also speaks frequently of religion, but not in the most positive sense. His short poem “Prayer”:

Whatever happens. Whatever

what is is is what

I want. Only that. But that.

He had a strong dislike for Christianity. Some of that can be seen in the long poem, written in the early 1960s, “The Avenue Bearing the Initial of Christ into the New World”:

A roadway of refuse from the teeming shores and ghettos

And the Caribbean Paradise, into the new ghetto and new paradise,

This God-forsaken Avenue bearing the initial of Christ.

Before reading this collected works, I had not read any Kinnell poetry. Although I was impressed with several poems his two most anthologized poems slipped by me– “St. Francis and the Sow” and “After Making Love We Hear Footsteps”. His poems from the from the 1970s and later poems appealed the most to me. The widespread of his poetry and the evolving topics will sure to find favor with other readers with different tastes than my own. As a collected work, Kinnell’s poems, show his growth and refinement as a poet. The introduction by Edward Hirsch will give the reader ample information and background on the poet and his poems. A well-done collection that will allow the reader to pick and choose his or her favorite topics or simply give the reader something to pick up and randomly read. - evilcyclist.wordpress.com/2017/09/25/poetry-review-the-collected-poems-of-galway-kinnell/

The tome of the work is presented in several sections reflecting publications and time. His earlier work takes the form of more traditional poetry with sights and feelings of his ports of call in the navy, particularly France and India.

What storms have blown me, and from where,

What dreams have drowned, or half dead, here

…

Each year I lived I watched the fissure

Between what was and what I wished for

Widen, until there was nothing left

But the gulf of emptiness.

The traditional form is partly owed to his admiration of Walt Whitman. He then moves to more of a “Beat” type of poetry. His work seems influenced by the movement even though he was not an active participant. His work in the late 1960s and 1970s moves much more into nature poems:

On the tidal mud just before sunset,

dozens of starfishes

were creeping. It was

as though the mud were a sky

and enormous, imperfect stars

moved across it slowly

as the actual stars cross heaven

In the 1980s through the 2000s Kinnell finds himself writing as an experienced sage. He relies on his personal experience and knowledge to create his mature works. Here, the poems reflect on aging and the death of those who were close and the lives of his children. Kinnell also speaks frequently of religion, but not in the most positive sense. His short poem “Prayer”:

Whatever happens. Whatever

what is is is what

I want. Only that. But that.

He had a strong dislike for Christianity. Some of that can be seen in the long poem, written in the early 1960s, “The Avenue Bearing the Initial of Christ into the New World”:

A roadway of refuse from the teeming shores and ghettos

And the Caribbean Paradise, into the new ghetto and new paradise,

This God-forsaken Avenue bearing the initial of Christ.

Before reading this collected works, I had not read any Kinnell poetry. Although I was impressed with several poems his two most anthologized poems slipped by me– “St. Francis and the Sow” and “After Making Love We Hear Footsteps”. His poems from the from the 1970s and later poems appealed the most to me. The widespread of his poetry and the evolving topics will sure to find favor with other readers with different tastes than my own. As a collected work, Kinnell’s poems, show his growth and refinement as a poet. The introduction by Edward Hirsch will give the reader ample information and background on the poet and his poems. A well-done collection that will allow the reader to pick and choose his or her favorite topics or simply give the reader something to pick up and randomly read. - evilcyclist.wordpress.com/2017/09/25/poetry-review-the-collected-poems-of-galway-kinnell/

Galway Kinnell was often compared to his favorite poet, Walt Whitman, whose "Crossing Brooklyn Ferry" Kinnell movingly read aloud every year on the far side of the Brooklyn Bridge at a benefit for the New York poetry library Poets House. Like Whitman, Kinnell — who died in 2014 having won the Pulitzer, the National Book Award and a MacArthur, among other honors for books published between the 1960 and 2006 — was a poet of capacious interest in the natural world, profound commitment to social justice, and deep sympathy for the people he saw.

He was a poet of his time, meaning both that he depicts the world, concerns and values of the last third of the 20th century, and that his poems are like those of many of his peers born at the end of the 1920s — A.R. Ammons, Philip Levine, W.S. Merwin and Adrienne Rich — who broke free of the strict formalism of 1950s American poetry to create the more impressionistic, sometimes surreal, nature-focused poetry of the late 1960s and 1970s. For many, Kinnell’s poems are exactly what one thinks of when one thinks of contemporary poetry. All of his books are collected here, along with a handful of late poems. It is impossible to consider the landscape of the last 50 years of American poetry without Kinnell.

Kinnell was inarguably a great poet. Among the subjects he was best at were steadfastness in marriage and parenthood. In his famous poem "After Making Love We Hear Footsteps," Kinnell's young son Fergus wanders into his parents' room when "we lie together, / after making love, quiet, touching along the length of our bodes, / familiar touch of the long-married." Then Fergus "flops down between us and hugs us and snuggles himself to sleep, / his face gleaming with satisfaction at being this very child." There is no ball and chain here, no ambitions crushed beneath the weight of child-rearing. Kinnell's world is enlarged and infinitely specified by his love for his family.

among the fat, overripe, icy, black blackberries

to eat blackberries for breakfast,

the stalks very prickly, a penalty

they earn for knowing the black art

of blackberry-making; and as I stand among them

lifting the stalks to my mouth, the ripest berries

fall almost unbidden to my tongue,

as words sometimes do ...

Kinnell's readers are granted constant and intimate access to his body, to his sensations, to what it feels like to taste and touch and see and hear and think as him. This was a profound priority, an invitation to empathy, to communion, that was essential to Kinnell's sense of what poetry could, and should, do. For him, the poet's work is to come as close to the world as possible with words, to express its contradictions and complexities in literally breathtaking detail, looking

until the other is utterly other, and then,

with hard effort, probably with tongue sticking out,

going over each difference again and this time

canceling it, until nothing is left but likeness

and suddenly oneness

At his best — and he is very often at his best — Kinnell is capable of transforming the world at hand — in both urban and country settings, for he split much of his life between New York and Vermont — into a grammar that can point us toward, be our access to, profundity, to truths, and what often feels like Truth itself.

Among Kinnell's most important late works is "When the Towers Fell," a long poem written after 9/11, which feels deeply prescient right now. Of the fallen towers, Kinnell says, "often we didn't see them, and now/ not seeing them, we see them." The truth of this applies to so much we'd taken for granted, the loss of which now overruns our news feeds. This poem represents a very personal working through of a very public tragedy by a deep and earthbound mind. Kinnell here trains his considerable descriptive powers on imagining what it was like to be in the towers when the planes struck: "Some let themselves fall, begging gravity to speed them to the ground. / Some leapt hand in hand that their fall down the sky might happen more lightly."

We need this poem again, and more poems like it, which ache to understand others' suffering, which suffer over a suddenly dashed dream of what could and should have been, what should be. Kinnell teaches that kind of attentiveness. - Craig Morgan Teicher

http://www.latimes.com/books/jacketcopy/la-ca-jc-galway-kinnell-20171201-story.html

http://www.latimes.com/books/jacketcopy/la-ca-jc-galway-kinnell-20171201-story.html

Galway Kinnell was an award-winning poet best known for poetry that connects the experiences of daily life to much larger poetic, spiritual, and cultural forces. Often focusing on the claims of nature and society on the individual, Kinnell’s poems explore psychological states in precise and sonorous free verse. Critic Morris Dickstein called Kinnell “one of the true master poets of his generation.” Dickstein added, “there are few others writing today in whose work we feel so strongly the full human presence.” Robert Langbaum observed in the American Poetry Review that “at a time when so many poets are content to be skillful and trivial, [Kinnell] speaks with a big voice about the whole of life.” Marked by his early experiences as a Civil Rights and anti-war activist, Kinnell’s socially-engaged verse broadened in his later years to seek the essential in human nature, often by engaging the natural and animal worlds. With a remarkable career spanning many decades, Kinnell’s Selected Poems (1980) won both a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award.

Kinnell was born in 1927 in Providence, Rhode Island and grew up in Pawtucket. A self-described introvert as a child, he grew up reading reclusive American writers such as Edgar Allan Poe and Emily Dickinson. After two years of service in the U.S. Navy, he earned a BA with highest honors from Princeton University—where he was classmates with poet W.S. Merwin—in 1948. He earned an MA from the University of Rochester a year later. Kinnell then spent many years abroad, including a Fulbright Fellowship in Paris and extended stays in Europe and the Middle East. Returning to the United States in the 1960s, Kinnell joined the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE), registering African American voters in the South. Many of his experiences—world travel, city life, harassment as a member of CORE and an anti-Vietnam war demonstrator—eventually found expression in his poetry. One of the first voices to mark the change in American poetry from the cerebral wit of the 1950s to the more liberated, political work of the ‘60s, Kinnell “is a poet of the landscape, a poet of soliloquy, a poet of the city’s underside and a poet who speaks for thieves, pushcart vendors and lumberjacks with an unforced simulation of the vernacular,” noted the Hudson Review contributor Vernon Young.

Of his first books, What a Kingdom it Was (1960), Flower Herding on Mount Monadnock (1964) and Body Rags (1968), Body Rags contains the bulk of Kinnell’s most praised and anthologized poems. Using animal experiences to explore human consciousness, Kinnell poems such as “The Bear” feature frank and often unlovely images. Kinnell’s embrace of the ugly is well-considered, though. As the author told the Los Angeles Times, “I’ve tried to carry my poetry as far as I could, to dwell on the ugly as fully, as far, and as long, as I could stomach it. Probably more than most poets I have included in my work the unpleasant because I think if you are ever going to find any kind of truth to poetry it has to be based on all of experience rather than on a narrow segment of cheerful events.” Though his poetry is rife with earthy images like animals, fire, blood, stars and insects, Kinnell does not consider himself to be a “nature poet.” In an interview with Daniela Gioseffi for Hayden’s Ferry Review, Kinnell noted, “I don’t recognize the distinction between nature poetry and, what would be the other thing? Human civilization poetry? We are creatures of the earth who build our elaborate cities and beavers are creatures of the earth who build their elaborate lodges and canal operations and dams, just as we do … Poems about other creatures may have political and social implications for us.”

Though obsessed with a personal set of concerns and mythologies, Kinnell does draw on the tradition of both his contemporaries and predecessors. Studying the work of Theodore Roethke and Robert Lowell, Kinnell’s innovations have “avoided studied ambiguity, and he has risked directness of address, precision of imagery, and experiments with surrealistic situations and images” according to a contributor for Contemporary Poetry. Critics most often compare Kinnell’s work to that of Walt Whitman, however, because of its transcendental philosophy and personal intensity; Kinnell himself edited The Essential Whitman (1987). As Robert Langbaum observed in American Poetry Review, “like the romantic poets to whose tradition he belongs, Kinnell tries to pull an immortality out of our mortality.”

Other well-known Kinnell works include The Book of Nightmares (1971) and The Avenue Bearing the Initial of Christ into the New World: Poems 1946-1964 (1974). The latter’s eponymous poem explores life on Avenue C in New York City’s Lower East Side, drawing inspiration from T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land.” A book-length poem that draws heavily on Rainer Maria Rilke’s Duino Elegies, the ten parts of The Book of Nightmares revolve around two autobiographical moments—the births of Kinnell’s daughter and son—while examining the relationship between society and community through a symbolic system that draws on cosmic metaphors. The book is one of Kinnell’s most highly praised. Rilke was a particularly important poet for Kinnell and among his many acts as a translator, he would later co-translate The Essential Rilke (1999), with Hannah Liebmann.

Selected Poems (1982), for which Kinnell won the Pulitzer Prize and was co-winner of the National Book Award in 1983, contains works from every period in the poet’s career and was released just shortly before he won a prestigious MacArthur Foundation grant. Almost twenty years after his Selected Poems, Kinnell released the retrospective collection, A New Selected Poems (2001), focusing on Kinnell’s poetry of the 1960s and 1970s. His poetry from this period features a fierce surrealism that also grapples with large questions of the human, the social and the natural. In the Boston Review, Richard Tillinghast commented that Kinnell’s work “is proof that poems can still be written, and written movingly and convincingly, on those subjects that in any age fascinate, quicken, disturb, confound, and sadden the hearts of men and women: eros, the family, mortality, the life of the spirit, war, the life of nations … [Kinnell] always meets existence head-on, without evasion or wishful thinking. When Kinnell is at the top of his form, there is no better poet writing in America.”

Kinnell’s last book, Strong is Your Hold (2006) was released the year before his 80th birthday. The book, which continues the more genial, meditative stance Kinnell has developed over the years, also includes the long poem “When the Towers Fell,” written about September 11, 2001. In an interview with Elizabeth Lund for the Christian Science Monitor Online, Kinnell declared, “It’s the poet’s job to figure out what’s happening within oneself, to figure out the connection between the self and the world, and to get it down in words that have a certain shape, that have a chance of lasting.” Lund noted that “Kinnell never seems to lose his center, or his compassion. He can make almost any situation, any loss, resonate. Indeed, much of his work leaves the reader with a delicious ache, a sense of wanting to look once more at whatever scene is passing.”

Kinnell lived in Vermont for many years, and he died in 2014 at the age of 87. - https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/galway-kinnell

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.