Patricia Eakins, Hungry Girls and Other Stories, Cadmus Editions, 1989

The title story won a Charles Angoff award in 1987 and this collection of thirteen connected stories, Eakins' first book, announces a new talent on the scene. As Paul Violi observes, “Eakins' work has the multifarious appeal of genius, and she may have written a major book. Certainly she has written a magical one.” These stories are a modern bestiary which rework the stuff of mythologies, spanning the cultures of the planet, reclaiming for the Imagination its territories from Science. They are counterfables in which the usual fabulous project is reversed: animal characteristics are attributed to humans, and humans and animals are seen as codeterminants of the moral and cultural landscape.

Eakins writes of terrifying pullulation [rapid breeding, swarming, teeming] with enormous charm; nature in her stories is gargantuan and omnivorous . . . life is a constant turmoil of metamorphoses, Heraclitian but marvelous strife. So many of her creatures, in their very genesis, even in their pre-natal state are already causing havoc, seething beneath the soil of edenic landscapes, bursting forth to reduce human affairs to defenseless absurdity. . . . Yet in virtually all of Eakins' stories, the beauty of life is redeeming; in this she reverses Rilke, as if to say, that beauty is not the beginning of terror, but survives it. For all their careful observation, the stories have the furious motion of myths . . . applied to familiar genres: the western, the feral child, the nuke mutant, the courtly Japanese tale, the Persian parable . . . their spiritual range is that of an encompassing vision.

A stunning mixture of mythology, surrealism, anthropology and nature, the thirteen stories in this collection are a tour-de-force of originality, imagination and style. From story to story, Eakins invents a fantastic bestiary which resembles at times the gentle and wise creation myths of primitive tribes and at others the dark sociological satire of Swift and Rabelais. These stories . . . exhibit a finely-honed, carefully constructed anti-realism; . . . a kind of attack on the highly conscious, rational, dualistic, scientific thought processes common to Western thinking in the modern age. The author seems to argue, with justification, that imagination and the unconscious are doors to understanding that have rusted shut on their hinges as a result of our over-reliance on reason. Borrowing from any number of conventions both sacred and profane, from contes fantastiques to creation myths to traditional Japanese courtier tales, these stories seek to provide, like the myths and fables they often emulate, explanations for mysteries beyond the kinds of knowing fostered by scientific thought. The Hungry Girls is quite simply one of the most intriguing and entertaining new collections of short fiction I have read in recent years. — Greg Boyd

Like some of the best poetry, these

tales dazzle and amuse us with their inventiveness, love of paradox,

and skill with language. - Enid Dame

What we have here in this collection is

the birth of a North American Borges — mental, clever, all puzzles

and riddles, lit as chess, mind-trek, with this difference . . .

whereas Borges is centered in dream, myth, the occult, the focus of

Eakins is a fantasy-biology in its widest sense. The whole book is

visioned through the naturalists' eye “ only (like Borges) this

naturalist is just a little surrealistically off center. Delicious

writing, a kind of fantastic bestiary. It has the bronze solidity and

permanence of major work . . . Romping through all-history,

all-geography, turning her fantastic animals into sociological

paradigms (Cf. Gulliver's Travels or Melville's Mardi), working out

absurd sociological models with utter tongue-in-cheek sobriety . . .

Eakins has thrown a puzzler at us more than anything else announces

the beginnings of the major phase of a major artist among us. —

Hugh Fox

Patricia Eakins must have grown up on

bestiaries because every story in her new collection is about some

sort of made-up animal, and like the medieval writers, she is very

moral about her creatures, except in her case the morals tend to be a

little disturbing. — Stuart Klawans

The Hungry Girls is an astonishingly

ambitious and accomplished book, especially considering the risks

Patricia Eakins takes. Writing in the genre of the fabulous tale, she

stakes a claim in territory pioneered by . . . Rabelais, yet her work

reveals a distinctive and often startling sensibility. The strength

and resonance of many of Eakins' stories come from her deft use of

the shocking. . . . At times the fantastical is no more than we might

see on the evening news . . . Eakins sometimes casts a devastatingly

cold eye on what human culture accepts as normal . . . Eakins

apparently believes in our need for story to make the world come

alive again. Even her most fantastical stories are tales of the human

condition. — Kathleen Norris

. . . Patricia Eakins tells us thirteen

tales of primal, disturbing beauty in an authoritative voice that is

both scientific and lush. Under the guidance of this storyteller, we

suspend our old ways of seeing and enter a mythic landscape where the

perverse becomes redemtive and the macabre becomes natural. Eakins'

tales . . . strip away sentimentality to reconnect us with old truths

and to reveal the world as it is: graced, mysterious, and brutal . .

. Eakins' book yields an astounding menagerie of life. Parable, epic,

folklore, fairy tale, saga — the teller houses her vision in each

of these forms to pass on a collection of wisdom that is rare in this

age of information. — Mary Lynn Skutley

Patricia Eakins' The Hungry Girls is as

rare a creature as those that populate its pages, a genuinely

original, beautiful, and disturbing work of art. It is a kind of

imaginative bestiary for our times, but a bestiary in the same sense

that Borges' Ficciones is a collection of myths or that Calvino's

Cosmicomics is a scientific treatise. And it shares with these works

a lightness of touch, comic wit, and astonishing inventiveness. — Robert Coover

An awesomely inventive tale-teller,

Patricia Eakins has created a world that is a mirror of our own (only

minus such human impediments as morality and memory). Its animals are

tantalizing in their trompe l'oeil reality, rendered with disarming

aplomb, and she sets them in fierce and unstoppable motion without a

blink to give away her game. That deadpan poise is what gives these

stories their rare menacing wit: Aren't these things possible? These

species sound so plausible, their behavior so—nearly—familiar . .

. Patricia Eakins writes beautifully: a fine ear and a sense of shape

make uncommon music of her direct imaginings. If you've had enough

fiction-as-usual — name brands, minor ephiphanies, timid time-bound

gestures — The Hungry Girls has some astounding things to tell. —

Roselyn Brown

What most distinguishes her work is a

thickness I'll call Geertzian, a packed quality — the excitement

and immediacy of lyric poetry . . . The test is the sentence. Power

is the word that comes to mind. The actual, physical presence of

energic mass, I mean energy/mass. It's the relentless electric charge

of the fiction. . . . The test is the sentence . . . In Eakins, there

is an integrity, an authority, everywhere at all times present and

accounting. — George Chambers

These stories are more than

imagination; they are witty, playful, soberly detailed glimses into

realities totally believable. These stories are wicked in their

conjoinment of what the eye sees and the heart and mind know. The

settings are convincingly detailed, the language of each story richly

native to it, and the animals are so living in their acts and

behaviours and relationships one knows they are real.

— Faye Kicknosway

The Hungry Girls is a continuously

startling work, an elegant violation of the rules of contemporary

fiction. Like gamelan music or like creation myths and tribal

histories, these stories have no real beginning or end. Each seems a

piece of some larger record—of a life, a people, a village, a

culture. In part their genius resides in the authenticity of each

story's tone and point of view and in part with the music and imagery

of the language itself, which is poetic and sensuous. One savors the

flow of words, sometimes rollicking, often disturbing, ever

mysterious and evocative. That we cannot quite say what these stories

mean speaks of the purity of their connection to the well-spring of

human creativity. The characters (whether men, women, beasts, or

something between) arise like dream figures, inexplicable, unless we

make them safe by reducing them to less than what they are. These are

stories that echo from so many regions of the psyche they confound

analysis, and finally we must take them of a piece both vivid and

bewildering. Finally it is their aesthetic to which we are drawn, the

intricate compilation of detail, evincing a rare and humbling

artistry. — Elizabeth Herr

More than stories in a collection,

Eakins' tales are palimpsests of cultures, the details of each

slightly effaced portrait glancing through the layers of cultural

imagination. With their faintly bizarre sexuality and their good

humor, they belong to the world of fable, not to the dusty archives

of academic anthropology—they are, in that sense, fabulous.

— Mariana Rexroth

In this first collection of fiction, Patricia Eakins's territory is in that tangled thicket of the imagination somewhere between Borges and Burroughs, between the fairy tales of Grimm and the magic realism of the South Americans, a kind of ''Invisible Cities'' as animal sanctuary, yet her oeuvre is in no way derivative. Each of Ms. Eakins's stories posits a separate, self-contained world with its own set of exemplary monsters. The hungry girls of the title story, who emerge almost literally from the soil - the eating of dirt seems to germinate them - have gargantuan indiscriminate appetites. With each successive generation of girls, they grow more grotesquely large until they become virtually as big as houses.

''The priest saw that each of the girls sitting on the ground had at least one young man living inside her. He saw the young men lean ladders against the hungry girls' sides so they could climb up on their shoulders and comb their hair and whisper in their ears. . . . One fellow drove a stage coach right into a girl's body, six horses and a sizeable carriage with a great deal of baggage on top and behind!''

This passage has a Marquesian wit. That the girls represent some kind of rampant nature, voracious and amoral, hardly explains the story's mystery. Ms. Eakins's stories refuse explication, remain exotically opaque.

''The Hungry Girls'' is about the primordial universe unmediated by the civilized and the rational, but it is also implicitly about the imagining of self-sustaining worlds, the making of convincing artifice. Patricia Eakins's language is in every way equal to her inventions. For example, the story ''Forrago'' starts: ''Now in the darkest and narrowest alleys of Porto Affraia, alleys too dark and narrow even for stand-up whores and small-time thieves, there thrive some small ratty creatures with greasy, ashen coats and greedy big eyes. The teeth of these fragaos, or forragos, are sharper than scimitars.'' Where the hunger of the hungry girls is a kind of fecundity run amok, the ratlike forragos are unmitigatedly vicious. Ms. Eakins's imaginary creatures have a visceral reality as powerful and convincing as the human characters in most of our realistic fictions.

Creatures like the banda, who are benign, tend to be more or less ineffectual. The banda's role is to warn children to avoid the path to the witch's house. But the banda ''has no vocal cords in his throat and his tongue is velvet. No wonder the child thought the banda's whisper was leaves, restless in wind. Still. The banda did the best he could.''

If the child follows the banda's advice, which he is only dimly aware of having heard, he can escape the witch. ''But it will not happen. It never does.'' The sentimental banda gives the witch an occasional minor comeuppance, but mostly leads a life mired in well-intentioned failure and the dim solace of regret.

Nature in Patricia Eakins's densely rendered universe is both evenhanded and arbitrary. ''The Hungry Girls'' gives us a dimly familiar version of our world, as perceived through a transforming imagination. It is a work of imaginative brilliance, a considerable achievement in modest disguise. In time, ''The Hungry Girls'' will no doubt find its audience. Meanwhile, readers interested in the pleasure of surprising fictions will go out of their way - it may be the only way - to find the Cadmus edition of Patricia Eakins's triumphantly quirky first book. - JONATHAN BAUMBACH

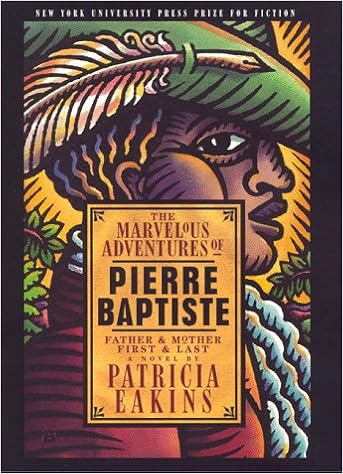

Patricia Eakins, The Marvelous Adventures of Pierre Baptiste: Father and Mother, First and Last, NYU Press, 1999

read it at Google Books

borrow it

The first-person narrative of a savant slave, Patricia Eakins's The Marvelous Adventures of Pierre Baptiste is one of the most imaginative novels in many years. From the opening pages, the reader is swept up by the linguistic fireworks of Eakins's autodidactic protagonist as he recounts "the tribulations of bondage in the sugar isles," his escape and how he was marooned, and his subsequent trials and adventures. Making expert use of historical convention and with an ear for rhetorical authenticity, Eakins has given us a compelling novel that bridges not only human cultures but the chasm between human and animal.

Here then is the account of the life and times of an African man of letters "whose ambitions were realized in strange and unexpected ways, yet who made peace with several gods and established a realm of equality & freedom & bounty in which no creature lives from another's labor." Pierre Baptiste emerges as an embodiment of all that is lost in a racist culture

First-novelist Eakins (The Hungry Girls & Other Stories—not reviewed) received the NYU Press Prize for this account of an 18th- century slave who becomes an autodidact, a philosopher, a castaway, and a mother and father both. Try, if you might, to imagine Robinson Crusoe’s Friday with Tristram Shandy’s education—and without Robinson Crusoe—and you—ll get some notion of what to expect in Eakins’s rather audacious tale. It’s narrated by one Pierre Baptiste de Buffon, an African slave who has spent most of his life in the Caribbean islands during the years leading up to the French Revolution. Pierre was purchased by an erudite and forward-thinking landowner who—in defiance of both law and custom—taught him how to read and write and eventually made him the manager of one of his estates. About as privileged as a slave could be, Pierre studied philosophy, science, and literature, and was able to converse with his master’s peers as an intellectual (if not a social) equal. He learned from them that a Revolution proclaiming the equality of all was convulsing France and threatening to spread across Europe. Determined to see at firsthand what was happening, Pierre ran away and tried to float across the Atlantic in a rum cask—only to run aground on an uninhabited island. Here the story turns into a veritable bestiary of the weird and unexpected. The impractical Pierre is hard-pressed to survive in the wild until he catches a wounded mermaid and nurses her back to health. She repays his charity by coming ashore each day and vomiting fish into his mouth. Eventually, Pierre discovers himself pregnant, and in due course he delivers four new “creatures” into the world. Presiding over this odd family, Pierre tames his island wilderness and tries to complete his “CYCLOPEDISH HISTOIRE OF GUINEE AND BEYOND” (i.e., the story of his life), which will probably go on for quite some time—if it’s ever finished at all. Bizarre, marvelous, and horrifying at once: a refreshing escape from the mundane. - Kirkus Reviews

The trials of a genius trapped in bondage supplies the framework for Eakins's first novel (after the short story collection The Hungry Girls), which purports to be the adventure-filled autobiography of an 18th-century black youth born into slavery on a sugar plantation. The plantation master, an amateur naturalist named Dufay, recalls 10-year-old Pierre from labor in the cane fields to help him classify flora and fauna on the Caribbean island. Impressed by young Pierre's acumen, and by his good humorAhe nicknames him GoodyADufay allows the boy to learn to read and write. Pierre often sneaks into the master's library to pore over volumes of Plato, Descartes, Newton and Diderot. After encountering a noted philosopher's condescending description of "Negroes," Pierre sets out to create the definitive encyclopedia of African culture: "In so doing, I would open for inspection THE GENIUS OF MY PEOPLE, proving we who had been stolen from Guine? THE EQUALS IN EVERY RESPECT OF OUR MASTERS and DESERVING OF LIBERTY." Later, when Pierre (now married to the hideously ugly but loving plantation cook) refuses to sleep with Madame Dufay, she accuses him of rape; Pierre sets out to sea in a barrel addressed to France. After an arduous experience, he is washed ashore on an uninhabited island. Here the novel's brilliance begins to tarnish. Pierre's commentaries on his Caribbean life are often scathing, humorous and brutally heartbreaking, but alone on his island, Pierre waxes tediously philosophical, and his adventures become weird, indeed: he is impregnated by a mermaidlike creature, carries the results to term in his mouth and gives birth to four "philosofish," whom he proceeds to educate. Such over-the-top, magic-realist bizarreness detracts from, and almost capsizes, what is for the most part startlingly creative, memorable work. (May) FYI: This novel won the NYU Press Prize for Fiction; excerpts have appeared in the Paris Review and other literary journals. - Publishers Weekly

Eakins' skill at spinning a tale and her love of language are obvious in this story of an eighteenth-century black slave who repeatedly defies convention and ultimately creates his own universe. Torn from his mother as an infant, Pierre is selected at age 10 to be his master's porter, thus gaining access to a library and becoming a self-educated man on the sugar plantation. He even successfully resists his master's attempt to breed him by selecting for his wife a woman known to be barren, as the result of horrific treatment at the hands of her previous owner. But when he deflects his mistress' advances, she threatens tortures worse than death, and he escapes from his island home by taking to sea in a barrel, thus embarking on fantastic adventures. The story is told in the style and language of the time and is studded with tales seemingly grounded in legend and myth. Eakins succeeds in her desire "to create stories that read as if they come from the body of lost history." - Michele Leber

Patricia Eakins's first novel is a fictional slave narrative that doesn't have a great deal to do with slavery. Eakins's hero, Pierre Baptiste, is a slave on the island of St.-Michel who, while recounting his ''marvelous adventures,'' is most concerned with presenting himself as a philosophe and an auteur. Eakins is clearly enamored of the trappings of the slave narrative; she supplies the broadside title page, the ampersands, the all-caps phrasing and the appeals to Kind Reader. While she puts Pierre through the obligatory genre paces (he educates himself, marries, escapes to freedom and commits his trials to paper), these incidents are handled perfunctorily, with no apparent regard for history or the human drama of enslavement. Betraying a faddish preoccupation with narrative and texts, Eakins has Pierre dream of writing a ''cyclopedish histoire of Guinee and beyond.'' Built to be deconstructed, the pretentious histoire veers from folk tale to science fiction/fantasy without rhyme, reason or a fraction of the humor and vitality of Charles Johnson's brilliant fictional slave narrative, ''Oxherding Tale.'' Here's one of Pierre's typical eruptions: ''Lost the Gods immortal, brothers and sisters, all far, far away. But for birds & ghosts & insects, I was alone. Oh, the insectae!'' The progression of events is equally incomprehensible -- it's ''Medea'' (a woman roasts her own infant, serving it to the baby's father); it's the Bible (Pierre is swallowed by a giant fish); it's ''Robinson Crusoe'' (Pierre is marooned on a desert isle); it's possibly even ''Charlotte's Web'' (Pierre befriends a female spider). It's a mess. - ELIZABETH JUDD

http://www.nytimes.com/books/99/06/27/bib/990627.rv014633.html

Everybody knows the yarn of the shipwrecked sailor, cast away on a tropical island. We’ve all also heard the tale of the noble slave who frees himself through his intellect and ability. Patricia Eakins builds her Marvelous Adventures of Pierre Baptiste from these time-honored strains — Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, Aphra Behn’s Oronooko and such — to create a story with the worn-smooth feeling of driftwood.

Eakins, though, does more than just retell. Aswim with references to Caribbean colonial life and the French 18th century, the book shows painstaking research. Nor does she just transpose plots; she appropriates colonizers’ stories, retelling them from the colonized perspective.

Eakins’ novel follows a sugarcane slave’s progress from his eavesdropped and stolen education, through his marriage to a voodoo witch to his flight from the plantation, eventually landing on a deserted island. Pierre’s negotiation between his ancestry and his adopted culture, during the plantation half of the book fascinates. With the journey, though, the ground falls away under him — Pierre falls into wild hallucinations, replacing his people’s stories with crazed visions. Eakins’ writing follows, trading balance for lurid incoherence, ending in the thin-veiled theorizing of the Tempest-cribbed end.

The ideas driving the book are politically laudable. But good politics hardly ensures good art. Her recombination of other fictions works like an intellectual’s shell game, but by the end of the novel it is abundantly clear that the shells are all empty. —Justin Bauer

http://mycitypaper.com/articles/061799/bq.quicks05.shtml

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.