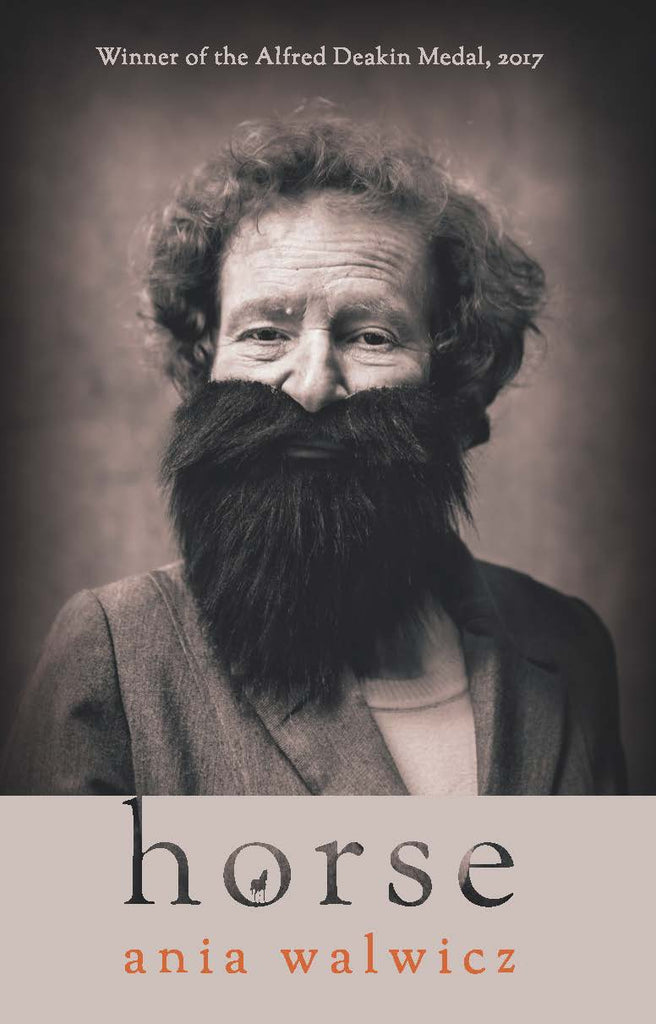

Ania Walwicz, horse, UWA Publishing, 2018.

Book extract

excerpt

Enter into the world of imaginative writing that crosses over into theories of language and the mind: A fairytale. Magic horse tells me. I grow a beard. Who is me? Work crosses boundaries between poetics, theory and autobiography. An opera of the self. I am the diva. Dark comedy and terror of psychoanalysis comes to life here. A learning experience. Layered text. I become the Doctor. The composition of the self. The work of memory, charm and play. Doctor Walwicz tells you a trauma. Doctor Freud reads me here. I know everything now and all at once. Fictocriticism. A multilevel text. You can do it too. I analyse me. You can do it to you. A different reading of the self. My diary. I tell you everything here. I open my head. I open my heart. Read me.

eaten away with a black hole now. He said that there were migranes caused just by the way the head is held now. When we were children. His father hurt me. Freud hurts me because he tells me and then he forgets me. He tells me and then he forgets me.I tell me and then I forget me. But I remember me here.It is the mouth And the digestive system. The Alimentary canal the network of my body . The pee pee and the poo poo. The medical diagram. The foot that withers. The arm that can’t bend. The back that is twisted.The illness of the body. Ieat sweets. I am given cakes and cakes and cakes. Sweet days. I smoke cigarettes of my grandfather in Vienna in the post office of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. I cough and cough now. I am Sigmund Freud and I smoke a cigar.I* am hurt by the tsar of Russia who keeps me in a cellar. Who traps me in the stable now in the abject stable now of abjection of Julia Kristeva.His name is Fritzl. He photograps me in a lake. Iam a little girl. He tells me I am I boy now .That I must wear trousers and looks best like that. He takes me to barber the bat barber. Iget short hair.i ride in sidecar of motorcycle now erlkoning speaks to me now come to me my child and come to me now come to me and come to me he knows these poems in german come to me and come to me and come to me now iam ania vanya stable boy in stable in hold position I bend over …”neurosis determined by period in which it originates … fixed in earlie!it childhood”.

This is a brilliant comic work…a wild horse turned loose in a field where its movements trace a transversal line through the ficto- and the critical so that the two become forces that acting on and through each other, so that there is no question of fencing them off…As this wild horse gallops it also shape-shifts- becomes a nightmare, becomes pony, becomes dream horse or rocking horse or dark horse. With each transformation, genres mix, collide or sometimes collude, and the field itself is reconfigured, and the forces within it are realigned. - Anna Gibbs

Ever since the seismic arrival of her amazing debut collection writing (Melbourne: Rigmarole 1980), Ania’s prose poetry has staked a claim worldwide for riotous parody and resistance in defiance of the marketplace of consumable story. In horse the rider is horseplayed as the horse is playridden, always en procès, in metamorphosis and on trial, pushing consumption to its bulimic and parodic limits… horse is a creative powerhouse: registers and quotes jostle: cultural and literary theory, psychoanalysis, children’s literature, high literature, cinema, and pop music, autofiction and current affair – all spark off in extraordinarily productive friction. - Marion May Campbell

Poet and avant-garde novelist Ania Walwicz's Horse will be an acquired taste. From the mischievous preamble, we're on notice that we're reading a work of "ficto-criticism", in a playful interleaving of autobiography, fairytale, literary (and dramatic) criticism, semiotic theory, automatic writing, and Jungian and Freudian psychoanalysis. I was more than a few times reminded of that Joyce line from Finnegans Wake: "they were yung and easily freudened" – not just for the sense of writing as therapy that animates this work, but for its puckish and compulsive wordplay. You'll certainly get a kick out of it if you're a fan of Gertrude Stein: Walwicz's constant phrasemaking and language puzzles are rhythmical and repetitive and witty in a similar way. For all its ironic layering and lit-crit filigree, there's a knot of trauma embodied in the book's disintegrating orbits of grammar and syntax; bleak unspeakables behind the jokey psychodrama and fragmented attempts to portray the self. - Cameron Woodhead

www.smh.com.au/entertainment/books/horse-review-ania-walwiczs-avantgarde-interleaving-of-forms-20180813-h13vxf.html

Virtuosic performance text, palimpsest of a nineteenth-century Russian folktale, and a merciless and often very funny sectioning of the self, Ania Walwicz’s horse enacts what it names: ‘Polyphony as identity’. The narrative more or less follows the story of The Little Humpbacked Horse by Piotr Jerszow, in which a magical horse repeatedly helps Ivan, a foolish young farm boy, towards his fairy-tale ending. In Walwicz’s wilder and more fragmentary retelling, the protagonist’s identity comprises both horse and rider, tsar and groom, tyrant and the tyrannised, abused child and academic, the self of fiction and the ‘autobiographical’. The effect is almost Cubist, in that all of these facets are visible without becoming a settled, realist literary image. - Bernard Cohen

https://www.australianbookreview.com.au/abr-online/current-issue/237-january-february-2019-no-408/5276-bernard-cohen-reviews-horse-by-ania-walwicz

Horse Preamble

Dear reader. I will tell you a story. This is a story of my life now. Dear reader turn away from these pages…They will only bring grief to me… It will only wound me and hurt me. But I must do it now. lch muss… Inner necessity. I have to do it now. I must.I have to. I have to do it now and do do do a doo doo … lt is imperative. I have to. This is something I have to do to save me. Dear reader, I’m in bits and pieces. I am a broken house. I am a puzzle. I have to place this together. This will glue me and repair me. This will build me. Buildingsroman. A constructive novel. A book. This is the theatre of my head in a theatre. I act this out. I enact me. I act out. I act up. I work this out. I am actor enactor of the inner theatre of Anna 0. This is the theatre of my head. I am my performance now. I become somebody else. I want to become somebody else who is me. I am a she looking for me. Somebody help me. Help me. I help me. I talk to me when nobody else… I talk when I can’t talk. I speak here where there is no speech or speaker. This is a page and a tape. This will be done and done with. This is the theatre in a theatre. I act my body now. I feel my finger tips when I cannot feel my finger. This will stop a dam from burst asunder. This will•keep a dyke from flood. I’m little Dutch boy. I keep the world, together. By doing this, just by doing this, just by this, exactly. I intend to travel back and travel forward. I aim high. I plan to fly and fly. I am making this up and this makes me into into somebody. I become my story. I put on costumes in my, the theatre of my head. A performative text and a performance now. I am speaking in your head. I put on a fur cap and red boots now. I act up. This is a play in a play. I enter a narrative, a fragmented narrative. I cut me up. Rumplestitskin. I tear myself in half when somebody knows my name, but nobody knows me now and I don’t know me. But I will know me. I aim to. I want to.I plan to. I will start with a little child. I will start with Swidnica, a little town. - Ania Walwicz

read more here

‘Language can multiply itself and form secret and unusual patterns’: Andrew Pascoe Interviews Ania Walwicz

Ania Walwicz, Boat, 1989.

Ania Walwicz, Red Roses, 1992.

Ania Walwicz and Phillip Hammial, "Travel" & "Writing", Angus &a Robertson, 1989.

Ania Walwicz, Elegant, Vagabond Press, 2013.

Elegant flight of language, theatre of my head, enactment, i never end, action, re-enactment, this can be done again and again and again, the loopy loop, sharp piercing, a sign, an elegant outfit.

A university tutor introduced me to Ania Walwicz’s writing when I was a young student. I remember being surprised by the sustained dynamism of red roses (UQP, 1992), a book-length poetic/ficto-critical meditation on ‘becoming one’s mother’: ‘i want to write about everybody’s mother everything is becoming my mother everyone is becoming my mother all texts speak about her’ (21). I had never realised how much I had come to rely on the conventions of grammar and syntax to guide literary representations of the world. Without punctuation or chapter breaks to pace reading, one proceeds breathless through Walwicz’ text and arrives at the ‘end’ somewhat exhausted. It is Walwicz’ desire to evoke what she calls a situation of complexity, rather than a situation of ease, for her readers.

Beneath this flouting of convention, however, Walwicz' works explore complex political, social, cultural and personal issues. Many of her prose poems in the collections Writing (1982), Boat (1989), Elegant (2013) and Palace of Culture (2014), for example, address questions of identity. As a Polish immigrant to Australia in 1963 (aged 12), Walwicz frequently touches on themes of alienation, subordination, dislocation and loss of language. In 'so little', for example:

We were so big there and could do everything. [...] My father was the tallest man in the world. Here we were nothing. There vet in the district and respect. The head of the returned soldiers and medals. Here washed floors in the serum laboratory. Shrinking man. I grow smaller everyday. The world gets too big for me. We were too small for this big country. We were so little. We were nothing. We were none and naught and no money. We were no speak. There we were big and big time. Here we were so little.

Other poems explore sexual identity; in 'Cherry', she draws a connection between sex(uality) and violence:

Cherry, cherry pie. Sugar baby. Baked these pies in New York. Very bright, very red. Cherry pie time now, then [...] My mother, she beat me. Made my nose run. Red lady. Cherry time.

And 'needle' suggests a complex process of stitching together self-identity:

i sew me i get a packet of needles i'm a needle now i'm sharp tip with a little eye i go right in i make me better i make me i sew me needles and pins that's how it begins

We can take pleasure in the stream-of-consciousness with which she continually flirts, the protest against control and linearity, the sense of feeling around in the dark through language for a point of release. Her most recent book The Palace of Culture begins at this entry point:

i begin i begin to i begin to dream i dream what i begin say say what you see now i dream about what i dream i have a dream now

Walwicz has kept a dream diary for more than 20 years and counts Surrealism, dream narratives, psychoanalysis and Freud in particular as some of her many influences. We note this in the fluidity of her writing style, and the sense of the language – with its slips and errors, looping and unexpected leaps in thought – being unmediated in the space between dream and page. As she has said, '[i]t appears that I am producing this dismembered language, but in fact I am producing language which is actual and closer to the actual process of feeling and thinking. My motto is: notation and enactment of states of feeling/being'. Ania's poetry – or experimental prose – provides a sort of channel experience, an in-between place to revel in.

Walwicz often combines these dream-like narratives with the use of fairytale mythology as a way towards exploring self-identity. We see this in the poem 'Little Red Riding Hood', where Little Red is appropriated to assert a rebellion against norms of female subordination. Carnal desire is flaunted but also delightfully dangerous:

I always had such a good time, good time, good time girl. Each and every day from morning to night. I was so lively, so livewire tense, such a highly pitched little. I was red, so red so red. I was a tomato. I was on the lookout for the wolf. Want some sweeties, mister?

Walwicz' writing is perennially naughty, with frequent intimations of a repressed, girlhood sexuality unleashed: 'oh mister bear come out now to eat me' ('palace at 4 a.m'). But alongside the humorous, frisky undertones, Walwicz' work also flirts with the dream as the space for the production of nightmare – a space where not only our desires, but our fears and anxieties come spilling out.

In Walwicz' writing, the fun and the whimsical co-exist with the grotesque and the horrible; inside erupts into clear view; one fears the bear and is compelled towards the bear, and even becomes the bear. Her work represents a loop-de-loop of the psyche, where the end is not the end, but a new beginning:

what will happen to me what next and what next tell me this drives me this takes me where it wants me till until i'm ready then i'm ready when i'm ready i'm ready i don't stop me

In addition to her books, Walwicz' work has been published in more than two-hundred journals and anthologies. She has performed her work locally and internationally (including a performance in Geneva alongside one of her inspirations, John Cage) and currently teaches Creative Writing in RMIT's Professional Writing and Editing program. - Jessica L. Wilkinson

https://www.poetryinternationalweb.net/pi/site/poet/item/26640/15/Ania-Walwicz

Ania Walwicz, Palace of Culture, Puncher & Wattmann, Sydney, 2014.

Reading the poetry of Ania Walwicz is a little like being drawn into a trance: the density of the prose-like lines; the disorientation of the lack of punctuation; the repetition of certain words, phrases, alliterations. It is not a poetry that can be read in short bursts. Each poem is a commitment to a vision, to a mind-space explicitly shaped by the intensity and demand of Walwicz’s language. Having burst into Australian poetry with her ‘Polish accented’ voice more than thirty years ago, troubling the dominant Anglocentric view of Australian culture, Walwicz’s poetic still works to startle a reader from her comfort zone and to disrupt her expectations about what poetry is and can be. - Rose Lucas

www.australianbookreview.com.au/abr-online/archive/2014/125-november-2014-no-366/2253-palace-of-culture-by-ania-walwicz

All Writing Is Pigshit

Ukulele Ekphrasis

Ania Walwicz is an Australian poet and play-wright, born in Swidnica, Poland, she emigrated to Australia in 1963 and was educated at Melbourne's Victorian College of Arts and the University. She has been a writer-in-residence at Australian universities and is well-known for performances of her work. She is widely admired for her highly experimental poetry, which rejects the conventional structures of free-verse in favour of the prose-poem form, but creates energetic rhythms through patterns of grammatical and tonal recurrence. Walwicz's principal collections include Writing (1982), re-issued as Travel/Writing in 1989, Boat (1989), and Red Roses (1992). Her theatrical pieces include Girlboytalk (1986), Dissecting Mice (1989), Elegant (1990), Elegant (2013), Palace of Culture (2014) and Horse (2018).

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.