Friederike Mayröcker, Scardanelli, Trans. by Jonathan Larson, The Song Cave, 2018.

excerpt

In SCARDANELLI, Friederike Mayröcker, one of the most well-known poets in Austria, associated with the experimental German writers and artists of the Wiener Gruppe, continues to sharpen her mystical and hallucinatory poetic voice. Filled with memory and loss, these poems are time-stamped and often dedicated to friends they address, including Friedrich Hölderlin--"I do often go in your shadow"--who appears in the first poem of the book and stays throughout. Even the title, SCARDANELLI, refers to the name that Hölderlin signed many of the poems with after having been diagnosed with madness toward the end of 1806. Mayröcker uses her own eclectic reading, daily life, and the scenes and sounds of Vienna to find a new language for grief and aging--"I am counted among the aging ones though I would prefer to consort with the young (rose of their cheeks)." Despite the intractable challenges Mayröcker's language and unconventional use of signs and symbols presents to translation, Jonathan Larson manages to convey masterfully the unmistakable singularity of her work.

Tumult, ferocity, flow, exaltation, immersion: Friederike Mayröcker, among the world’s greatest living writers, reinterprets literary vocation as total theater. Swimming through the language-tide, she cuts syntax into new folds and undulations. Responding to her gestural commands, words form constellations, clusters, diaristic strings of inference. Like Kandinsky, she oscillates between abstraction and figuration, and treats phrase-groupings as pungent, aimed vectors, ambushing the senses from the picture-plane’s four corners with floral insinuations and hermetic explosions. She doesn’t narrate; she amplifies and conjures, turning linguistic intake into a synesthetic, intertextual act of voracious reincorporation. Jonathan Larson’s gorgeous translation does Rosenkavalier service, mediating Mayröcker and tuning Scardanelli’s luster into Anglophone receivers. Mayröcker’s bouquet—a notebook, an event, a demand—gives Ponge a run for his money. —Wayne Koestenbaum

Very consistently, in verse and prose, [Friederike Mayröcker] has combined collage procedures with fantasy and free association, relying on the imaginative power, elegance and inventiveness of her language alone to make up for the loss of referential coherence, linear plots in prose or ‘subjects’, as distinct from themes, in poems. Her combinations of the most disparate material have their being in total freedom. —Michael Hamburger

Formally and linguistically bold, these poems from Mayröcker make their way through an uncharted territory. That comparison isn’t made lightly: there’s a dimensional and tactile quality to many of these poems that gives the reader a lingering sense of specific spaces—and a startling feeling of being yanked out of them when Mayröcker opts for an abrupt ending of transition, as she frequently does in these works.” - Tobias Carroll

https://www.wordswithoutborders.org/dispatches/article/the-watchlist-december-2018-tobias-carroll

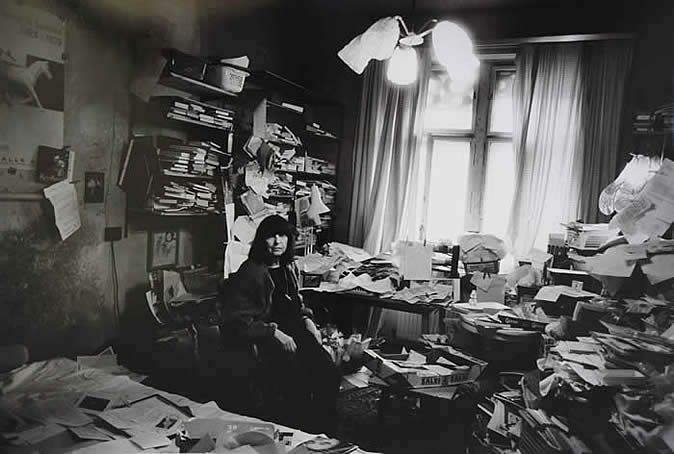

Among Austria’s most celebrated poets and author of over 100 books, Friederike Mayröcker often arrives before American audiences via a description of the one-bedroom apartment/writing studio she has inhabited since the 1950s. Google image searches find her there, hunched over a typewriter and surrounded by colossal piles of books and papers — think Kurt Schwitters’s Merzbau meets Jay DeFeo’s The Rose meets Francis Bacon’s studio. Mention of her lifelong partnership and her collaborations with fellow experimental poet Ernst Jandl, begun in 1954 and lasting until his death in 2000, often directly follows this description. Despite the problems of framing any female writer’s work with these two elements of domesticity — in her home and with her celebrated male partner — I’m compelled to repeat these snippets because they so vividly symbolize the layering and communication that give rise to the genius of Mayröcker’s texts.

Scardanelli, translated by Jonathan Larson and released in English this November by The Song Cave, is titled after the nom de plume with which Friedrich Hölderlin signed his poems after he had gone mad in 1806. All of the book’s poems bear some relationship to Hölderlin, quoting from his late work and incorporating imagery — meadow, grove, sheep, violets, wanderer — found in his late poems. Yet, Scardanelli is not an attempt to occupy Hölderlin’s nom de plume, but rather a book written in the company of other writers, Hölderlin chief among them. Dated and ordered chronologically, Mayröcker wrote all but the first poem in her eighth decade, after the death of Jandl, and Scarandelli’s existential tone reflects this. It discloses being as a state of impermanence, made of absence, while simultaneously so alive with traces of language, objects, and memory that pure absence, absolute death, are revealed to be false concepts.

“Hölderlin tower, on the Neckar river, in May” opens the book with this confluence of absence and trace. The title references the tower where he lived in the town of Tübingen, until his death in 1843. Written on the occasion of a 1989 reading at the tower, the poem clearly develops from the experience of inhabiting what was once Hölderlin’s physical space and draws attention to both acute absence and presence:

Unlike “Hölderlin tower” most of Scarandelli’s poems don’t remain cinematically in a singular setting but float in location and memory, anchored in the act of composition. This includes distinctly remembered spaces like the “bright-red-Hölderlin-room,” but also Mayröcker’s studio and the abundant textual material that is physically present in her piles of books and papers as well as within the archive of her mind. Remembered moments conjured up at “the machine,” as Mayröcker calls her typewriter, lead to layers of quotations, often citing the original writer’s name directly in the text. This practice at the machine creates networks of experience and memory, composition and life. There is nothing outside of the text:this pinch of Hölderlinin the bright-red Hölderlin-room /in the corridor standingmy gaze drifts to the red flowers in the glassedged with fallenpetalsnothing else /the room empty only the vase the flowerstwo old chairs—I open 1 windowin the garden you say the treesare still the same ones they were thenbut 1 hears 1 sound of music thereglistens the bluish silver-wavefor Valerie Lawitschka6/6/89

As with so much of Mayröcker’s work, Scarandelli’s intertextuality runs deep and spans both literary and non-literary sources: Mayröcker tells writing students that they should read 10 hours a day; she immediately writes things down even while on the phone and these snippets become part of her texts. Furthermore, nearly all of Scardanelli’s poems are dedicated to specific people, calling to mind Frank O’Hara’s sentiment that “the poem is between two persons” and extending each poem beyond the author. The poem, offered in the poet’s absence, manifests a very present act of communication.[…] as I opened the window wide the breath’s tender movementsof summer (the alarm clock buried under linens : scraps of paper with notesthat after only several hours I will not be capable of de-ciphering — just as the screed-floor covered with unopened letters that I skidand as if on ice-skates. .), the beauty of the delirium in 1’s heart.

Along with dedications, date stamps, quotations, and references to composition, Mayröcker’s other signature movements repeat across poems, weaving individual utterances into the textual body that is Scarandelli. Like “Hölderlin’s tower,” most of these are a single stanza and begin in medias res with a lowercase letter. Most unfold in a single breath-thought with few, if any, periods breaking up ideas, thus creating a music of parataxis that moves in rounded, inclusive gestures rather than jumpy accretion. Slashes, dashes, italics, and words set in all caps are not infrequent, although most curious is Mayröcker’s use of the digit “1” as we see in “I open 1 window” and “but 1 hears 1 sound of music there.” Larson’s “Translator’s Note,” which follows his eloquent and informative introduction to Mayröcker’s oeuvre, tells us that “both the indefinite article ein/e/n/m/r/s and the number eins are represented with the digit 1.” In addition, klein (small or little in German) is rendered as kl.) and einmal (one time) is written in digits as 1 x.

Larson points out that this uncommon orthography provokes “an active reading in German where the reader provides the agreeing declension in the case of the adjectives and articles” and “the effect shared among these are a resistance to typographical standardization in favor of a pliable language.” The use of the digit 1 also suggests a subject-object relationship that questions boundaries between self and world, proposing the unity of being and language. The integration of subject and object, self and other, reified in typography and collage techniques, also emerges in slippages of imagery. Take, for example, the opening lines of “life’s billowing wave Höld. actually deathlet”:

“life’s billowing wave” begins back at the Hölderlin tower, in memory conveyed through fairly realistic description until the fourth line turns with “shores of abundant blos-/ soms resin in my heads.” Casually and mid-stride over the transformative nothing that is the end of a line Mayröcker multiplies the speaker’s head into a plurality, “heads,” identifying with the “abundant blos-/soms.” In the very next line she shape-shifts again, recognizing her “own shadow” in the “ ‘shadows of 1/dog in the river’.” Language slipping along so seamlessly in rounded inclusion brings these identifications into being, not as ruptures of a singular speaker, but as part of 1 subject’s nature.Tübingen as we trotted along the narrow meadow-path : the mead-ow-path trotting along the Neckar to the left as it already flowed andflooded for centuries as its waves accompanied us being therewe trotted on past herb-gardenlets on shores of abundant blos-soms resin in my heads, that time I noted “shadows of 1dog in the river”, it was my own shadow and still lingering alongthe path the flowers while the sounds the nightingale shy,Hölderlin — thus greened living ivy THE HIGH-SPIRITS : that time

While this network of subject and object appears throughout Mayröcker’s oeuvre, it takes on rapt poignance in a book framed by conversation with Hölderlin/Scarandelli. Hölderlin’s poetry of the Open, his madness, his taking up a pen name, throw the boundaries and nature of the self into question. As he proclaimed in his short 1795 philosophical text “On Judgment and Being,” “Where Subject and Object are absolutely, not just partially united … there and not otherwise can we talk of an absolute Being.” Mayröcker innovates squarely within this tradition and there has been no other time as in need of such vision. -

https://hyperallergic.com/470141/scardanelli-friederike-mayrocker-jonathan-larson-2018/

The author of well over one hundred works of poetry and prose, including theatrical and musical productions, as well as children’s books, Friederike Mayröcker has been awarded every German-language prize literature has to offer. With breathless abandon, she has continually expanded her oeuvre and exploded notions of genre and convention, while always getting to the heart of this earthly living by invoking what Friedrich Hölderlin referred to as “poetic dwelling.”

Her first major collection, Death by Muses, appeared in 1966. The book associated her with the Vienna Group—which included her longtime partner, Ernst Jandl—and a poetics concerned with formal stricture that was loosely identified as concrete poetry in the 1950s and ’60s. Mayröcker’s writings after this period can be read as an outgrowth of these earlier conceptual interrogations of literary expression. Her writing about—as in around—the self (a preoccupation Jacques Derrida termed circumfession) animated new approaches remarkable if not astonishing in their singularity. The rush of this work absorbed phrases emitted from the gramophone and telephone, and all manner of scraps from literature and memory, walks, trips, sedentary hours, as well as the rhythms of growth and decay, all put into an orbit of enchanted bricolage.

Mayröcker, now ninety-two, has penned three recent works, études (2013), cahier (2014), and fleurs (2016), which are especially daring in their pursuit of an ever-evolving form to grasp the outer and inner limits of a language for determining whether or how “the time of life is measurable.” Pathos and Swallow is the title of her latest collection, which she had just completed before our conversation. —Jonathan Larson

read the interview (Bomb)

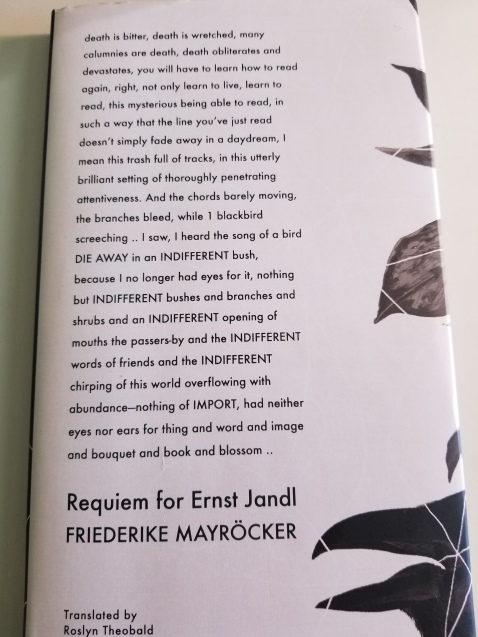

Friederike Mayröcker, Requiem for Ernst Jandl, Trans. by Roslyn Theobald, Seagull Books, 2018.

Austrian poet and playwright Ernst Jandl died in 2000, leaving behind his partner, poet Friederike Mayröcker—and bringing to an end a half century of shared life, and shared literary work. Mayröcker immediately began attempting to come to terms with his death in the way that poets struggling with loss have done for millennia: by writing.

Requiem for Ernst Jandl is the powerfully moving outcome. In this quiet but passionate lament that grows into a song of enthralling intensity, Mayröcker recalls memories and shared experiences, and—with the sudden, piercing perception of regrets that often accompany grief—reads Jandl’s works in a new light. Alarmed by a sudden, existential emptiness, she reflects on the future, and the possibility of going on with her life and work in the absence of the person who, as we see in this elegy, was a constant conversational and creative partner.

Requiem for Ernst Jandl is the powerfully moving outcome. In this quiet but passionate lament that grows into a song of enthralling intensity, Mayröcker recalls memories and shared experiences, and—with the sudden, piercing perception of regrets that often accompany grief—reads Jandl’s works in a new light. Alarmed by a sudden, existential emptiness, she reflects on the future, and the possibility of going on with her life and work in the absence of the person who, as we see in this elegy, was a constant conversational and creative partner.

"A magnificent translation. . . [Theobald] gives us an autofictional masterpiece of raw emotion, that will resonate with anyone who has ever given thought to how quickly life passes. . . . A web of associations and recollections, Requiem for Ernst Jandl is full of references to both the dead and the living, to literary theorists and to poets, to friends with their advice for the bereaved, and to places both real and dreamed up – and most of all, to Jandl himself. Through the powerful immediacy of her at times heart-wrenching language, Mayröcker proves that grief does not have to be private and can acquire a dignity that triumphs over any worry about decency." - Times Literary Supplement

Friederike Mayröcker and Ernst Jandl lived together from 1954 until Jandl’s death in 2000. They were lovers, companions, friends and creative partners; as we read Mayröcker’s elegy to Jundl the feeling of being lost and bewildered without him pervades her text. In a partnership that spans more than forty years, it’s fascinating to see what images and thoughts she brings to her poetic reflection on their time together. After spending so much of her life and her passions with him, how could she possibly choose what to write about in order to honor properly their memories?

One of my favorite pieces in the book is a reflection on a poem fragment that Jandl writes that is stuffed, with many other literary fragments, into his desk. In the winter of ’88 the two are painstakingly excavating the contents of his desk and Mayröcker recollects:

thebookbindersdaughter.com/2018/04/24/in-the-kitchen-it-is-cold-requiem-for-ernst-jundl-by-friederike-mayrocker/

One of my favorite pieces in the book is a reflection on a poem fragment that Jandl writes that is stuffed, with many other literary fragments, into his desk. In the winter of ’88 the two are painstakingly excavating the contents of his desk and Mayröcker recollects:

Afternoon after afternoon, actually the entire

winter of ’88, we are absorbed in

viewing, approving, conserving what

has been written down. And then, suddenly,

one day I come across four lines

dashed off in pencil:

winter of ’88, we are absorbed in

viewing, approving, conserving what

has been written down. And then, suddenly,

one day I come across four lines

dashed off in pencil:

in the kitchen it is cold

winter has an awful hold

mother’s left her stove of course

and i shiver like a horse.

She goes on to connect the poem to her current state of grief over Jandl’s passing:winter has an awful hold

mother’s left her stove of course

and i shiver like a horse.

The last line, which informs of the most

profound abandonment, aloneness, exclusion

seeking solace in an attempt

to identify with that mute creature—a carriage

horse in winter’s cold depths, standing

in one place for hours, head hanging, in no

one’s care, waiting for a human to get it

going—is so poignant.

And it is the very last line of the poem that haunts Mayröcker:profound abandonment, aloneness, exclusion

seeking solace in an attempt

to identify with that mute creature—a carriage

horse in winter’s cold depths, standing

in one place for hours, head hanging, in no

one’s care, waiting for a human to get it

going—is so poignant.

This line: mother is not at her stove:

conveys the damnable utterly graceless

transience and finiteness of this life, mother

is not at her stove—where did she go.

I’ve read two other books on grief recently: Will Daddario’s To Grieve and Max Porter’s Grief is a Thing with Feathers. Of all these, Mayrocker’s text elicited the most emotional response from me. Her multifaceted response to grief in all its forms—emotional, philosophical, social—struck a nerve. - Melissa Beckconveys the damnable utterly graceless

transience and finiteness of this life, mother

is not at her stove—where did she go.

thebookbindersdaughter.com/2018/04/24/in-the-kitchen-it-is-cold-requiem-for-ernst-jundl-by-friederike-mayrocker/

Friederike Mayröcker, brütt, or The Sighing Gardens, Trans. by Roslyn Theobald, Northwestern University Press, 2007.

read it at Google Books

brütt, or The Sighing Gardens is the hallucinatory tale of an obsessive writer’s love affair late in life as told through the daily journal entries of the writer—a montage of relentless observation interspersed with found materials from newspaper articles, literature, and private correspondence. The process of aging and the process of writing are two persistent and carefully intertwined themes, though it is apparent that plot and theme are subordinate to the linguistic experiments that Friederike Mayröcker performs as she explores them. Mayröcker is known for crossing the boundaries of literary forms and in her prose work she creates a hypnotic, slurred narrative stream that is formally seamless while simultaneously overstepping all the bounds of grammar and style. She is always pushing to expose the limits of language and explore its experimental potential, seeking a re-ordering of the world through the re-ordering of words. Her multilayered texts are reminiscent of the traditions of Surrealism and Dadaism and display influences from the works of Beckett, Hölderlin, Freud, and Barthes. Yet, much of Mayrocker’s writing simply has no corollary and the experience of reading Roslyn Theobald’s brilliant translation grants the English-speaking audience an unforgettable encounter with this completely original work.

The book I most want to celebrate for its formal innovations and its gorgeous weirdness is the Austrian poet Friederike Mayröcker’s torrential novel brütt, or The Sighing Gardens (translated by Roslyn Theobald, 2008). I can’t really call it a novel. It’s a sequence of rapid-fire love-struck cabalettas, strung together with minimal punctuation (just comma, colon, comma), in the ranting, cloacal mode of Thomas Bernhard. - Wayne Koestenbaum

"Friederike Mayrocker enjoys a growing reputation as a writer whose art insistently crosses the boundaries between literary forms. Her prose is lyrical, and draws on the work of a wide range of modernist writers, from Gertrude Stein to Virginia Woolf. Beckett and Thomas Bernhard have also influenced her style of bombarding the reader with a mixture of realistic and fantastic images. The device forces the reader to participate in the mental drama which supplants narrative in her work. [A]n ambitious project, often lyrical and intense, and altogether a tour de force." - Times Literary Supplement

"Friederike Mayrocker presents her readers with many puzzles; but among the numerous, currently inflationary topics of autobiographical prose, her work crystallizes the central issues." - Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung

"As much as the text defies description, it also indicates future possibilities for poetry. Anyone drawn into the tow of the book will continue to write it for him or herself." - Lesezirkel, Vienna

“I MUST FORGET EVERYTHING in order to finish this work, you have to get yourself in harness, no enmeshed, once you get involved in a writing project a writing diktat, there is no going back, or everything will be ruined, isn’t that right, maybe it’s getting your claw hooked into the robe of language, you attach yourself, you get snared, you get snagged in language in the MATERIAL in the TEXTURE, etc., and in the same way language seems to get hooked, attached, it hooks its claws into us the moment we acquiesce, so, we lead we guide each other, in equal measure . . .”

–Friederike Mayröcker, brütt, or The Sighing Gardens

–Friederike Mayröcker, brütt, or The Sighing Gardens

Reading Friederike Mayröcker’s brütt, or The Sighing Gardens (Northwestern University Press, 2008), translated by Roslyn Theobald. Part of the newish Avant-Garde and Modernism Collection series of that press—Haroldo de Campos’s Novas is, too—under the general editorship of Rainer Rumold and Marjorie Perloff. Mayröcker (b. 1924), long a leading figure of the German post-war avant-garde, and long associated with Ernst Jandl, publish’d the book in 1998: one figures it written by a seventy-plus year old Mayröcker.

In the form of dated entries, Mayröcker’s “I” considers a rather empty quotidian of sharp reveries and sporadic naps, books pick’d up and put down, letters written and received. The writing itself—syntactically skippy, with cherish’d oddments of emphases, or sudden OUTPOURINGS OF THE MAJESCULAR—is fleet and sidewinding (slurry) simultaneously, lashing out here and there to include whatever swings up out of the daily rhythm, the gone, the current, the wayward. It is punctuated by (drawn up into a temporal frame by) several stock epithets unchanging: “I tell Blum” or “I write to Joseph” or “X (or William or Ferdinand) writes to me” or “Elisabeth von Samsonow writes.” So the universe of the book becomes one of stories exchanged, or sentences exchanged, a language parade (and growing old, and writing). Though I mark’d innumerable terrific air-sucking lines (Mayröcker’s particularly good at implanting sudden fiercely piercing images, seemingly out of nowhere, completely odd), it’s likely that it’s the cumulative effect, the gentle assault that’s typique. Mayröcker:

And, because I found a copy of Thomas Bernhard’s The Loser (because one “character” in it is “Glenn Gould”) and’d been plowing around rather aimlessly in it, I found a passage by Bernhard that rather echo’d some of Mayröcker. He writes about how, after spending “six weeks in uninterrupted writing” about Glenn Gould, writing the book in hand:

In the form of dated entries, Mayröcker’s “I” considers a rather empty quotidian of sharp reveries and sporadic naps, books pick’d up and put down, letters written and received. The writing itself—syntactically skippy, with cherish’d oddments of emphases, or sudden OUTPOURINGS OF THE MAJESCULAR—is fleet and sidewinding (slurry) simultaneously, lashing out here and there to include whatever swings up out of the daily rhythm, the gone, the current, the wayward. It is punctuated by (drawn up into a temporal frame by) several stock epithets unchanging: “I tell Blum” or “I write to Joseph” or “X (or William or Ferdinand) writes to me” or “Elisabeth von Samsonow writes.” So the universe of the book becomes one of stories exchanged, or sentences exchanged, a language parade (and growing old, and writing). Though I mark’d innumerable terrific air-sucking lines (Mayröcker’s particularly good at implanting sudden fiercely piercing images, seemingly out of nowhere, completely odd), it’s likely that it’s the cumulative effect, the gentle assault that’s typique. Mayröcker:

I say to Blum: language history, I say, everything is language history, we just don’t want to admit it. Where options are left open to us, I say, where options are left open to us in a work of art, we start searching in vain for some kind of rules to follow, I misread the address of the sender, instead of Schillerplatz : Achillesplatz, I wonder if there is any kind of connection here?, I couldn’t tell, was that car in the dark coming toward me or headed away, instead of writing the address “München” most of the time “Mündchen,” it occurred to me early this morning that I’m trying for a kind of NOVELNESS in my most recent work, I am striving for NOVELNESS, whatever that means, I say to Blum, what do you think about the transitions in your work, a journalist wants to know, but I don’t know what to think, I tell him : this constant, I believe impassioned attitude of fantasy (and so not actual fantasy) is still an overarching influence, and saw tears on the amputated tree, glittering gold-colored tears of resin, I say, saw roses on tall stems, wilting robinias along the boulevards, the shrimp on my plate, that is the entire secret, or as Botho Strauß says : SUDDENLY THE END RIGHT IN THE MIDDLE OF THE DRESSING ROOM . . but sometimes, I tell Blum, when I take stock of everything, in these miserable, barren hours, it happens that I find myself having to say : I have done everything wrong, I have lost everything, wasted, missed, I headed off in the wrong direction, maybe the AESTHETICS OF LANGUAGE, which has been at the heart of my work since the beginning, was simply the wrong goal in the earthshakingly monstrous times, oh, the composites did it to me, the composers, the strolling, as Elisabeth von Samsonow writes, in her mind she sees me the way I was strolling in her ocher-colored handwriting, an ocher-colored woman’s hand with red border around the wrist, offering me a small bouquet of spring flowers, now in the middle of autumn, I tell Blum, stars in bright colors, plump green stems cut in uneven lengths, bundled together with a double cord, long-legged out of water (climbing) . . .Elsewhere I scribbled the comment that Mayröcker’s poems “remind me of Bernadette Meyer,” and add’d, “some remind me (sparsely) of Joseph Ceravolo, both, undoubtedly, false etymologies, skew’d impossible lineages. ‘Of the international graphomaniac tradition.’” I think of neither in the case of brütt, Ceravolo lacking the heft and pull, Mayer the dada piquancies—things like Mayröcker’s “scribbled down on small folded mauve-colored napkins, my little finger gliding like a ribbon of syrup across the empty page” or “my transit body is exhausted, I lie down on a sleeping mat, a lark is shooting salvos around inside my skull.” Though I do keeping thinking something like cette écriture féminine qui n’en est pas une, this writing that exceeds writing, all overlap and splash, uncontainable and there, all-encompassing in the same moment. Mayröcker’s approving quote of Bataille: “The wind outside is writing this book.” Or Mayröcker’s writing, in a kind of damning comparison?

I never write anything down, says Blum in a rather distant tone of voice, before I have thought it through completely and understand it, Blum says, language is a tumult, I say, like the senses, like ecstasy, clearly our libidos are controlled by our brains, isn’t that so, I say, last night’s housefly has gone back into action, a page full of scribbles . . .Reminding me somewhat of Luce Irigaray’s argument for a “language in which ‘she’ goes off in all directions and in which ‘he’ is unable to discern the coherence of any meaning”: “Woman has sex organs just about everywhere. She experiences pleasure almost everywhere . . . The geography of her pleasure is much more diversified, more multiple in its differences, more complex, more subtle, than is imagined—in an imaginary [system] centered a bit too much on one and the same.”

And, because I found a copy of Thomas Bernhard’s The Loser (because one “character” in it is “Glenn Gould”) and’d been plowing around rather aimlessly in it, I found a passage by Bernhard that rather echo’d some of Mayröcker. He writes about how, after spending “six weeks in uninterrupted writing” about Glenn Gould, writing the book in hand:

In the end . . . I had only sketches for this work in my pocket and I destroyed these sketches because they suddenly became an obstacle to my work rather than a help, I had made too many sketches, this tendency has already ruined many of my works; we have to make sketches for a work, but if we make too many sketches we ruin everything . . .Versus (and is the difference one of degrees, Bernhard struggling, in fact, to throw over the pre-knowing?) Mayröcker’s insistence that:

I MUST FORGET EVERYTHING in order to finish this work, you have to get yourself in harness, no enmeshed, once you get involved in a writing project a writing diktat, there is no going back, or everything will be ruined, isn’t that right, maybe it’s getting your claw hooked into the robe of language, you attach yourself, you get snared, you get snagged in language in the MATERIAL in the TEXTURE, etc., and in the same way language seems to get hooked, attached, it hooks its claws into us the moment we acquiesce, so, we lead we guide each other, in equal measure . . .Vatic voice as claw in the lingual firmament, I do love it so. - John Latta

The two terms of the title, brütt and die seufzenden Gärten, signify the contradictory aspects of love, according the author: the former referring to its brutality and pain, the latter to tenderness and surrender. For although Friederike Mayröcker has a reputation as an experimental writer who would never dream of providing a coherent narrative line, this current "novel" is being billed as a "love story."

Her avant-garde following need not become alarmed, however, for this is certainly no conventional "love story" and there is no need to fear that she might have lapsed into sentimentality ("the sighing gardens"!) or any semblance of a plot. Beginning with the statement "Ich erlebe nun eine Liebesgeschichte: meine letzte' muß es heißen" (I'm now experiencing a love story: my last one, it should be said), everything is fragmented and relativized by the author. Rather than a love story in any traditional sense, Mayröcker's novel is an extended meditation on the effect of love on a middle-aged, avant-garde writer: what does it do to how she perceives the world, how she articulates her pain and surrender, her sense of narrative and language?

It is never really clear if "Joseph," the putative object of her affections, is actually a figment of the narrator's imagination, providing her with an incentive to write "eine Art Tagebuch" (a form of diary) of this affair and its aftermath. In a series of dated entries, she records details of her experience in love along with a running commentary on the effect of her longing on her writing and her subjectivity. The "diary," written in the first person, begins on 9 Septebmer and covers the period until 4 July of the following year. The entries consist of the narrator's thoughts and observations on the topics of love, life, aging, literature, philosophy, esthetics, art, music; wordplays; fantastic sequences; recurring phrases and passages used like a theme and variations in music; and word-collages in Mayröcker's ironic, distanced, idiosyncratic prose, punctuation (:/!), and typesetting style.... The main questions for the unintiated reader may be, perhaps: who is the object of this love story.

Is it Joseph, one of a series of formulaic male ciphers including "X. (oder Wilhelm oder Ferdinand)," who recur throughout the text? Or is it "Blum," the one constant partner in the narrator's life, with whom she "converses" in each entry and who seems to understand her broad-ranging interests and to appreaciate her style. "Blum" is the other component of the dialogic principle governing the process of the narrator's writing: "sage ich zu Blum," "sagt Blum," "Blum fragt mich," "antworte ich Blum." Although "Joseph" seems to be the cause of her suffering, and although she speaks directly to him at times, he leads her into the temptation of "narrative" banality; "Blum," however, serves as her esthetic conscience, helping her "1 GANZ BESTIMMTE SCHREIB-HALTUNG BEIBEHALTEN ZU KOENNEN, usw" (to be able to maintain 1 very definite style of writing, etc.).

If you are a fan of Mayröcker already, or if you delight in non-narrative verbal pyrotechnics pushing the limits of language, this is the "love story" for you. It's brilliant in its use of and discourse on language. If, however, you are the type of reader looking for a coherent plot, passion, or romance in any traditional sense—sigh!—you are in for a rude (brütt?) awakening. [Susan Cocalis, World Literature Today] - Susan Cocalis

Her avant-garde following need not become alarmed, however, for this is certainly no conventional "love story" and there is no need to fear that she might have lapsed into sentimentality ("the sighing gardens"!) or any semblance of a plot. Beginning with the statement "Ich erlebe nun eine Liebesgeschichte: meine letzte' muß es heißen" (I'm now experiencing a love story: my last one, it should be said), everything is fragmented and relativized by the author. Rather than a love story in any traditional sense, Mayröcker's novel is an extended meditation on the effect of love on a middle-aged, avant-garde writer: what does it do to how she perceives the world, how she articulates her pain and surrender, her sense of narrative and language?

It is never really clear if "Joseph," the putative object of her affections, is actually a figment of the narrator's imagination, providing her with an incentive to write "eine Art Tagebuch" (a form of diary) of this affair and its aftermath. In a series of dated entries, she records details of her experience in love along with a running commentary on the effect of her longing on her writing and her subjectivity. The "diary," written in the first person, begins on 9 Septebmer and covers the period until 4 July of the following year. The entries consist of the narrator's thoughts and observations on the topics of love, life, aging, literature, philosophy, esthetics, art, music; wordplays; fantastic sequences; recurring phrases and passages used like a theme and variations in music; and word-collages in Mayröcker's ironic, distanced, idiosyncratic prose, punctuation (:/!), and typesetting style.... The main questions for the unintiated reader may be, perhaps: who is the object of this love story.

Is it Joseph, one of a series of formulaic male ciphers including "X. (oder Wilhelm oder Ferdinand)," who recur throughout the text? Or is it "Blum," the one constant partner in the narrator's life, with whom she "converses" in each entry and who seems to understand her broad-ranging interests and to appreaciate her style. "Blum" is the other component of the dialogic principle governing the process of the narrator's writing: "sage ich zu Blum," "sagt Blum," "Blum fragt mich," "antworte ich Blum." Although "Joseph" seems to be the cause of her suffering, and although she speaks directly to him at times, he leads her into the temptation of "narrative" banality; "Blum," however, serves as her esthetic conscience, helping her "1 GANZ BESTIMMTE SCHREIB-HALTUNG BEIBEHALTEN ZU KOENNEN, usw" (to be able to maintain 1 very definite style of writing, etc.).

If you are a fan of Mayröcker already, or if you delight in non-narrative verbal pyrotechnics pushing the limits of language, this is the "love story" for you. It's brilliant in its use of and discourse on language. If, however, you are the type of reader looking for a coherent plot, passion, or romance in any traditional sense—sigh!—you are in for a rude (brütt?) awakening. [Susan Cocalis, World Literature Today] - Susan Cocalis

Friederike Mayröcker, Night Train, Trans. by Beth Bjorklund, Ariadne Press, 1992.

More than an account of a train trip from Paris to Vienna, Night Train depicts a journey through life, as conceived by the female narrator. In poetic prose that is as magical as it is honest, the speaker reflects on issues such as time, childhood, and the process of aging. In light of our ultimate destination of death, the question reverts to what it means to be alive. Life is seen as an opportunity for self-development, that is, for creativity coupled with sexuality, which for an author means writing.

In 1969, at the age of forty-five, Friederike Mayröcker took early retirement from her job as a secondary school teacher, retreated into an almost hermit-like existence surrounded by unruly mountains of books, papers and notes in a tiny flat in the Zentagasse district of Vienna, and started to produce the main body of her extraordinary avant-garde literary work. After having written more than eighty books, won numerous awards and been nominated for the Nobel Literature Prize, she has, at last, had a major selection of her poetry translated and published in English. Raving Language: Selected Poems 1946-2006, translated by Richard Dove, came out last year from Carcanet press. It provides an excellent introduction to her work and a quite unique reading experience.

Two of the most frequently used words when attempting to describe that experience seem to be ‘hallucinatory’ and ‘magical’. These are not adjectives that come easily to the pen of modern and post-modern critics but they are accurate descriptions of the almost physical effect brought about by immersing oneself in the waterfalllike bombardment of this author’s poetry. The range of her poems, and the baroque nature of her imagery, is dizzying: we are taken, often within the space of a line or two, from surrealist fantasy to detailed naturalistic observation, from a reminder to see the oculist to heartfelt elegy. Mayröcker herself in a 2004 interview describes, somewhat warily in case she ruins the spell, the condition into which she enters in order to write (or into which she is sent by her writing) as drug-like or magical. One poem talks, in fact, of taking a ‘snort of Hölderlin’, and there does seem a sense of the intoxication that Mayröcker seeks in her reading and writing being essential, addictive and freeing: ‘hold it in your hands read it/ with your eyes, or you can sever the twine with the knife (the writing grows/ lively), or you can do it the other way round, hold/ in your eyes read with your hands, but in each case/ it says LIBERATION THROUGH READING.’

Repeated listening to particular pieces of music (Maria Callas crops up frequently in the poems) and reading voraciously are Mayröcker’s preferred ways of entering into this state.

At Vienna’s Schule für Dichtung (‘Poetry Academy’), she recommended to probably horrified student writers that they read for at least ten hours a day, for, as she states in another poem, ‘writing is applied reading’. Her reading which, from the twentieth century includes Breton, Artaud, Bataille, Michaux, Derrida, Barthes and Beckett, frequently finds its way into her writing in a central montage technique which she first developed in the sixties at a time when colleagues of hers in the Wiener Gruppe were moving instead towards an atomisation of language in their experiments with concrete poetry. The way Mayröcker’s reading, writing and daily living feed each other and are seamlessly woven together gives one the feeling that the whole of her art and life forms one grand collage in the manner of the Dadaist and fellow ‘rag picker’ Kurt Schwitters and his series of merzbau or collaged environments which he built around himself throughout his life like a snail growing a succession of shells. I am also reminded of the Palais Idéal of the obsessive French outsider artist ‘Facteur Cheval’ who collected rocks on his rural postal round to create the fantastical buildings of his dreams, including his own mausoleum.

The seemingly obsessive nature of Mayröcker’s gathering, arranging and transforming of materials is a quality she shares with another of the master collagists of the twentieth century, Joseph Cornell. Phrases in her poetry seem to me to be strikingly similar to some of Cornell’s diary entries where he records his epiphanies and manic episodes, and the sense of their work as a gift, or as an attempt to set up an exchange or conversation with others whether living or dead, is also something they have in common. Many of Mayröcker’s poems are dedicated to friends, writers and artists; most frequently to her life-long lover and fellow writer Ernst Jandl whose death in 2000 precipitated a flood of elegiac and often frenzied or raving work which succeeds in ‘getting madness’ into the language to represent her experience, and what she has described as the ‘heart-rendingness of things’, more faithfully.

I’m writing deluded letters whichyou’ll never receive, such thin andvulnerable skin-intercourse, this ismerciful weather, the whitethroat’skiss in the gardens. this word in thewire in communion I’m dreaming ofyou, and ecstasy itself, this magpie,have just invented language ravinglanguage.

To have invented language is perhaps as outrageous a claim as those often made by another of her favourite writers, Gertrude Stein, but reading Mayröcker’s late grief-soaked and yet still wildly leaping work it feels justified. At times though her language can be extremely simple and tender:

mother, eighty-three, hospitalthe gingko tree by the open windowof the hospital roomis spreading out its armsis that a gingko tree, she says,there’s something else youcan write aboutthe nun looking after hercomes to her bed and saysdo you want to confess and takecommunion tomorrowand holds her handI say she’s without sin,always has beenthe white-stockingedfinches among the leaves

If there is raving and rapture in her poetry (and like Christopher Smart she can resort suddenly both to capital letters and to her knees), it is not without irony: ‘on knees of desire was feverish in a minor key in the guest house/ today’ – from ON KNEES OF DESIRE OF DESIRE TO WRITE CRAWLING, PILGRIMISING. Nor is her writing without control. ‘What is indispensable’, she has written, in a note which Richard Dove quotes in his helpful introduction to Raving Language, ‘is the opening of all flood-gates while maintaining the strictest standards and exercising ruthless discipline and rigour’. There is wildness in the first and second drafts, she has said, but the iron fist comes in with the third and fourth.

Mayröcker is also a prolific writer of books of poetic and emotionally engaging but emphatically nonnarrative prose; nowhere in the world, she has claimed, can she see evidence of story. One of the key works in this category, ‘brütt, or The Sighing Gardens’, has also just been published in English by Northwestern University Press. The last poem in Raving Language is entitled ‘have got a flow of poems now’. Long may the flow of her writing and these very welcome translations continue. - Jeremy Over

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.