Syeus Mottel, CHARAS, The Improbable Dome Builders, The Song Cave & Pioneers Work, 2017.[1973.]

Introduction written by R. Buckminster Fuller.

Includes a new interview between Michael Ben-Eli & Ben Estes.

CHARAS, The Improbable Dome Builders is Syeus Mottel's documentation of a community in New York's Lower East Side in the early 1970s, and their desire to build a geodesic dome in a reclaimed vacant lot underneath the Manhattan Bridge.

Among the city's struggling street life and systemic racism, Carlos “Chino” Garcia and Angelo Gonzalez, Jr., two friends that had been involved in gang life from an early age, are at the center of the group called CHARAS.

Influenced by R. Buckminster Fuller's teachings, and personally mentored by Fuller's assistant, Michael Ben-Eli, the young men of CHARAS began a period of devoted study of solid geometry, spherical trigonometry, and the principles of dome building. Following this period, CHARAS developed a program that encouraged community autonomy and the reclaiming of public space.

More than simply a documentation of the project, the book offers stories, interviews with each CHARAS member, over 200 photographs, and a record of the group’s process, from their intensive study to the obstacles they faced while physically constructing domes. Several of the other men who would join CHARAS were also ex gang leaders or members, and had been moved in and out of the prison system while watching friends and loved ones succumb to drugs, poverty and violence. Touching on a range of topics still very relevant today, including affordable housing, community autonomy, education and rehabilitation, “This book is dedicated to everything that is.”

First published by Drake Publishers in 1973, The Song Cave is very excited to co-publish this new edition with Pioneer Works.

Syeus Mottel, freelance photographer and media consultant for Buckminster Fuller, spent the months between September 1972 and January 1973 documenting and interviewing the community of CHARAS, a grassroots organization made up of ex–gang members in the Lower East Side. After creating a storefront school for themselves and supporting local businesses, they wanted to tackle issues of affordable housing. They asked Fuller to give a talk to the group and, after deliberations, agreed to consider the geodesic dome as a model to challenge their community’s lack of agency over their urban space.

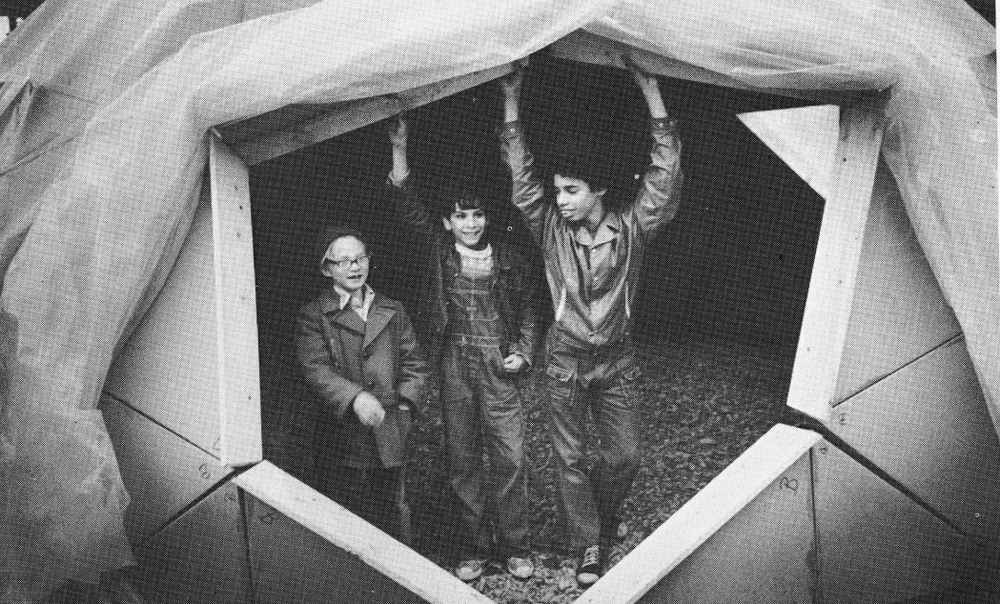

The photographs here, all Untitled, 1972/73, show CHARAS members watching television in their loft headquarters at 303 Cherry Street, a dome’s rain-protective polyethylene sheet inflating in the wind, and children and women holding 3-D tessellated models. One picture depicts an unlikely family-style portrait taken after the group constructed a sixty-foot dome on an empty lot—only two blocks from this gallery’s location—on a day when a jovial Bucky came to visit. Fuller is shown lovingly grasping a bored-looking child, flanked by his assistant, his wife, and the protagonists of the project; the dome in the background sinks into the earth like an asteroid.

Unlike the Southwestern dome communities born out of a hippie “turn on, tune in, drop out” ethos, the adoption of the dome by CHARAS can be read as more radical. The narrative, however, doesn’t account for what happened after Mottel’s part public relations, part documentarian stint. On the ultimate failure of the domes, Stewart Brand—publisher of the countercultural periodical Whole Earth Catalog—wrote that his generation left the domes behind like “hatchlings leaving their eggshells.” As the group watched Bucky climb into the back of a cab to leave the site, did they feel left behind, or led forward? — Nolan Boomer

As a kid in the 1980s, I was fascinated by a book that sat on a shelf in the living room of my family’s apartment on the Upper West Side. On its cover was an otherworldly dome set down like an alien spacecraft in a vacant urban landscape. To me, it looked like a cool work of science fiction, especially among a collection of volumes by R. Buckminster Fuller with titles like Utopia or Oblivion and Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth. This book, however, was different: CHARAS: The Improbable Dome Builders was created by my father, Syeus Mottel.

Born in the Bronx in 1930, Syeus grew up in New York and became a theatrical activist and photographer with interests all across the city. He was part of the Directors Unit of the Actors Studio in the ’50s, with Lee Strasberg serving as a sort of second father. Movie projects included a stint as the on-screen photographer in William Greaves’s 1968 meta-film Symbiopsychotaxiplasm, shot largely in Central Park. In the early ’60s, Syeus had met Bruce Davidson, a Magnum Photos member who became his mentor, and in the decades that followed, he chronicled his own life with his Leica and an observant photographer’s eye. He documented the cultural events he attended as well as the political and social movements of the era.

At the time, Fuller’s futuristic visions were popular among countercultural dropouts disengaged from politics and mired in self-exploration. But that wasn’t Syeus. He was a socially active citizen who felt that Fuller offered practical solutions to man-made problems—certainly more so than apolitical artistic movements (Fluxus, Pop art, et al.) that were not doing enough to change society for the better.

In 1968 Syeus took photographs at a lecture by Fuller in New York and sent them to him as a gift. In return, he received a personally signed response praising what Fuller called the best photographs of himself he had ever seen—and offering Syeus a job as a media consultant. He took on the duty and, a few years later, after another lecture, Fuller asked if he would accompany him downtown to meet a group of dome builders. He hopped in the cab, and that was how he crossed into the world of CHARAS.

Chino Garcia, Humberto Crespo, Angelo González Jr., Roy Battiste, Anthony Figueroa, and Sal Becker: CHARAS was an acronym of its founders’ first names. The six men, all in their twenties at the time, lived on the Lower East Side. New York City then was a collage, some parts dense with newly minted skyscrapers and other parts barren—negative space on a tattered map marked by corruption, lack of funds, and disregard. Large swaths of Manhattan were derelict or abandoned, especially downtown. In 1968 the future founders of CHARAS attended a lecture Fuller gave at the headquarters of the Real Great Society, a primarily Puerto Rican community organization, and heard him describe his design for the geodesic dome.

Since the 1930s, Fuller had been trying to mass-produce a low-cost, low-impact dwelling that could help ease the housing shortage in the United States. His first attempt was the easy-to-assemble Dymaxion House, which failed to take off. Fuller then developed the design for his geodesic dome during his time at Black Mountain College in the late ’40s. The dome utilized the strength of a triangular structure, as opposed to the square or rectangular shape of a brick. A network of triangles, interconnected, could create a spherical structure of considerable strength. The dome design epitomized Fuller’s theory of “doing more with less,” and it could be enlisted to address housing needs in an efficient and economically viable manner. He shared his vision with the world at the 1954 Milan Triennale.

CHARAS formed in 1969, after its six founders went on an Outward Bound expedition to Mexico. There, they learned survival skills and experienced communal living. When they returned to New York, they were determined to raise Fuller’s domes in their struggling neighborhood, to provide low-cost housing on their own in the absence of governmental support.

Garcia later wrote “A Step Towards the Future,” an essay in which he laid out CHARAS’s intentions. “My general feeling is that I am living in a fragmented society and concrete civilization built by a monster economy for greed and not in the interest of the humans that live a hard life,” he wrote. “A group such as CHARAS has gotten together to develop a concept of more humanized labor and living facilities in the interests of everyone.” Among their goals was “showing people from the ghettos how to organize themselves to design for their future.” Their message was urgent. “We have to start designing now,” he wrote, “knowing that in 30 years the population will be fantastically greater and our problems will also be greater.”

In 1970 CHARAS learned of a city program for community organizations to obtain open loft space in condemned buildings. For $5 a month, they rented a new 2,500-square-foot headquarters just a few blocks north of the Manhattan Bridge. In the loft, they built temporary domes with simple canvas and wood, in a fashion they repeated for public events across the city. In 1971 a $15,000 grant from the New York State Council on the Arts provided funding they needed to switch to cement in the service of more permanent structures. In the fall of 1972, they began construction on a large dome on a parcel of rubble-strewn land next door to their loft, at 303 Cherry Street. Within six months, it was complete.

Construction on a geodesic dome.

SYEUS MOTTEL/COURTESY MATTHEW MOTTELBut shortly after, the story ended—or at least a part of it did. Rather than seed the urban landscape with livable domes and alternative solutions for housing problems, CHARAS: The Improbable Dome Builders all but disappeared. Drake went out of business in 1975; the book fell into obscurity. My father fought to get it back in print, making entreaties to just about every major publisher in business at the time. Fuller’s books, he reasoned, routinely sold hundreds of thousands of copies—so who wouldn’t be interested in a meeting of his theories with real life? Alas, he found no takers.

In the meantime, CHARAS continued its activities. In 1978 the group converted a spacious former school near Tompkins Square Park into an open-source community center where their culture and politics could blend with the brimming East Village art scene in an egalitarian atmosphere not yet clouded by real-estate speculation and gentrification. During CHARAS’s residency, which would continue for 20 years, Sonic Youth played a benefit gig there. Filmmaker Jeff Preiss curated an experimental film series. Jemeel Moondoc shared studio space with the scuzz-rock band Royal Trux.

In 1979 Syeus got married and focused on family life. I was born in 1981, when he was 50 years old. He became a professor of media studies at a Manhattan community college, but it would be many years before I understood the full significance of his archive. When I was 17, I went to see the legendary electronic-music group Silver Apples perform, and Syeus casually said, “Oh, the Silver Apples were friends. I photographed them.” He went on to tell me of others whose pictures he had taken: John Cage, Ornette Coleman, Thelonious Monk, Paul Newman. As a punk teen, I had fixated on the generation gap between us, but our mutual cultural interests drew us closer for the rest of my dad’s time on earth.

In 2010, when I was an artist-in-residence at Issue Project Room in Brooklyn, I made an audio-visual performance piece, titled Osmotic Imagination, using parts of Syeus’s vast photographic records. I projected candid street photos of Martin Luther King Jr. beside pictures of William S. Burroughs, Abbie Hoffman, Miles Davis, Patti Smith, and many other artists who—independent of any direct familial influence—had become of monumental importance to my own art. At the performance, Syeus thanked me for resurrecting memories that he had forgotten.

With that commission, I decided to become the archivist and curator of his collection. In the years since his passing in 2014, I have found and digitized riches from more than 500 folders of contact sheets that include photos of a Vito Acconci poetry performance at Robert Rauschenberg’s studio, Diane Arbus speaking with the blind Viking musician Moondog on 57th Street, and Charlotte Moorman leading an avant-garde art parade through Central Park. My hope at the start was that the Syeus Mottel archive could become an open-source document for other investigators of culture to discover and use.

In summer 2016, Ben Estes and Alan Felsenthal of the Song Cave, an art and poetry press whose mission statement focuses on “recovering a lost sensibility and creating a new one,” contacted me to inquire about CHARAS: The Improbable Dome Builders. They were interested in republishing it, they said, since the book had come to be considered a gem among collectors and urban-studies experts. They brought the project to the Brooklyn-based exhibition and residency space Pioneer Works, which signed on as co-publisher. This past summer, Situations gallery on the Lower East Side—two blocks from where the Cherry Street domes had been built—presented an exhibition dedicated to CHARAS: The Improbable Dome Builders in advance of its republication this fall. More than 40 years after my father conceived it, the book is back in the world.

A geodesic dome built by the group CHARAS in New York in 1970.

SYEUS MOTTEL/COURTESY MATTHEW MOTTELVisitors to the gallery often asked, “What happened—how long did the domes last?” They lasted a few months, I said, but the larger purpose of the domes was to highlight the need to create affordable housing. The need remains, though not because of abandoned land. In “Tenants Under Siege: Inside New York City’s Housing Crisis,” an extensive article published by the New York Review of Books during the run of the show, Michael Greenberg surveyed grim realities for all but the rich in the city, with real estate prices rising and rent controls falling away. Since 2007, at least 172,000 apartments in the city have been deregulated, and the eviction of tenants as a result has led to a marked increase in “severe overcrowding.”

The plot of land at 303 Cherry Street is no longer vacant. But it plays home to what might be part of a solution still: 1,500 units of affordable housing for low- and moderate-income tenants in buildings constructed by the neighborhood organization Two Bridges between 1972 and 1997.

The vision of CHARAS lives on. - MATTHEW MOTTEL

http://www.artnews.com/2017/12/20/back-future-writer-explores-fathers-past-geodesic-domes-new-york/

SITUATIONS is pleased to present the photography of Syeus Mottel (b. 1930-2014) in an exhibition titled CHARAS: The Improbable Dome Builders, opening August 4th and on view through the 26th. The show was curated with Ben Estes, of poetry imprint The Song Cave, in conjunction with their upcoming re-release of Mottel’s 1973 book of the same title. Through the lens of avant-garde architectural theory, Mottel’s work touches upon topics ranging from the morals of city planning and affordable housing, rehabilitation and education, public vs. private space, and the need to strengthen inner-city communities.Mottel documented many important figures of the 20th century including Martin Luther King Jr., Ornette Coleman, Thelonious Monk, John Cage, and the Silver Apples. However, the focus of this exhibition is on a project in which CHARAS, a group of six ex-gang members, built a Bucky Dome with directives sought from R. Buckminster Fuller. More than 100 photographs and slides documenting Mottel's time with CHARAS will be on display.

In 1970 CHARAS held a meeting in an empty loft of a condemned factory building in the Lower East Side of Manhattan with R. Buckminster Fuller, the celebrated and revolutionary architect and inventor of the geodesic dome. CHARAS was interested in physically altering the housing conditions available in their immediate neighborhood, the Lower East Side. Unfortunately, their skills were basic and their educational background limited. After a few hours, and despite the seemingly impossible barriers between “Bucky” and CHARAS, they found themselves having an earnest and important conversation, and with the excitement and commitment between them all becoming apparent, the young men of CHARAS decided that they wanted to begin actively implementing Bucky’s ideas, and create a program to develop a sense of community autonomy, reclaim public space, and give their lives a new found sense of purpose.

After a period devoted to the intensive study of solid geometry, spherical trigonometry, principles of dome building, and a myriad of related subjects conducted by Bucky’s assistant, Michael Ben-Eli, CHARAS broke ground to construct a geodesic dome for their community on an unused plot of land in the shadow of the Manhattan bridge. Mottel documents the trials and tribulations of getting the dome built, including CHARAS’s intensive training, search for funding, accidental fires, holiday potlucks, and Bucky himself coming to the building site to see their incredible work. The photographs reveal intimate portraits of these ex-gang leaders and drug addicts, turned community leaders, who found a new sense self through the applied philosophies of Buckminster Fuller.These photographs have a significant relationship to the gallery since the dome was built two blocks from the gallery’s current location. As our neighborhood faces old and new challenges, it seems especially important to revisit Mottel's work and subject matter.

https://www.situations.us/syeus-mottel-charas-the-improbable-dome-builders/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.