Mark Beyer, Agony, New York Review Comics, 2016.

excerpt

ENJOY THE ECSTASY OF AGONY. Amy and Jordan are just like us: hoping for the best, even when things go from bad to worse. They are menaced by bears, beheaded by ghosts, and hunted by the cops, but still they struggle on, bickering and reconciling, scraping together the rent and trying to find a decent movie. It’s the perfect solace for anxious modern minds, courtesy of one of the great innovators of American comics. Now if only Amy’s skin would grow back ...

This NYRC edition features a recreation of the original, pocket-size, slipcovered paperback, designed by Art Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly.

“Mark Beyer’s 'Amy and Jordan' was one of the great underground comic strips of the late ’80s and early ’90s — the Candide-on-PCP misadventures of a seemingly accursed New York City couple.” —Douglas Wolk, The New York Times Book Review

"Almost childlike in its energy and lack of story logic, this is a charming explosion of grotesque comedic misfortune, exactly as the title promises...Beyer’s calamitous comedy has aged well, its geometric, densely patterned imagery recalling fine art as much as comics and still packing a punch among today’s alternative cartoonists.” —Publishers Weekly, PW Picks

"Exquisitely, gleefully hopeless." —The A. V. Club

"I couldn’t get enough of their misery: I finished it in one sitting and flipped back to the beginning.” —The Paris Review Daily Blog

"Mark Beyer’s Agony is a highlight of the 80s art comics movement... Now available in a new edition as the first release of the New York Review Comics line, the abstract, absurd, and bleakly funny comic book returns, and it’s just as oddly beautiful and relevant as ever. ...Throughout Agony, Beyer’s artwork is odd, alienating, and remarkably effective. A self-taught artist whose work could easily be classified as outsider, raw, brut, or naïve art, Beyer strikes a balance between simple, even childlike figure-work supported by a very dynamic and complex design."— Comics Alliance

"Gorgeously madcap and brutally inspiring.” —Kirkus Reviews

“Agony by Mark Beyer is an otherworldly pocket-sized jewel that’s bound to be rediscovered.” —Blouin Artinfo

“Beyer’s work is universal at its heart ... One of the masters of the form.” —Publishers Weekly

“Mark Beyer’s are some of my favorite comics of all time, and surely the most perfectly realized vision of urban despair ever to hit the comic page. A must for any fan of bleakness and misery." —Daniel Clowes

“He’s one of the flukiest geniuses in comics." —L.A. Weekly

“Exquisite poems of urban despair, dreamy and nightmarish.” —Chip Kidd

“Perhaps the ultimate urban nightmare comic...Mark Beyer [is] not only an extremely funny cartoonist, but one of the most progressive as well.” —Time

“A childhood hell palpitating with adult neuroses.” —The Village Voice

“Beyer’s seminal strip is a terrifying New York of the mind.” —Dash Shaw

“I hope Mark Beyer’s work will find a place in the canon...A treasure of the comics medium.” —The Millions

“A complete and total original.” —Kaz

In the 80's I grew up loving RAW Magazine and anything to do with it. One of their regular artists was Mark Beyer. He was a naive artist who took perverse pleasure in satirizing the hardships of life.

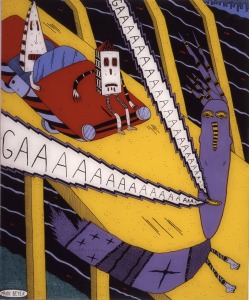

RAW Magazine came out with many solo works by their artists that they called One-Shots. Agony was Mark Beyer's RAW One Shot. In it he put his reoccurring characters, Amy and Jordan, two androgynous beings that look like a cross between a human and an amoeba, through their torturous paces for no other reason than because it is fun. The thing that makes Mark Beyer's work so fascinating is his imagination and sense of design. He does the most creative and interesting things on the page and he is not limited by normal esthetics or sense of anatomy. His characters live in a universe all their own with it's own laws of physics. It's awesome to see what new and interesting ways Beyer comes up with to depict the tortures of Amy and Jordan. Even though the subject matter that Mark Beyer writes about is dark I think there is a lot of life and joy in his work. Just look at all the love and care he put into each panel! And the book is 173 pages long! Personally I find this work totally stimulating and beautiful the way a Hieronymus Bosch painting is. You love to pour over all the incredible detail and marvel at the originality of all the crazy tortures he depicts just like in works like The Garden of Earthly Delights or study the fascinating detail of this world you think you should know but can't quite make out the way you do an Yves Tanguy painting.

http://thegreatcomicbookheroes.blogspot.com/2013/09/agony-by-mark-beyer.html

Originally published by Art Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly's RAW Books, and featuring characters that appeared in several issues of RAW magazine, Mark Beyer's Agony is a highlight of the 80s art comics movement, spearheaded by that landmark publication. Now available in a new edition as the first release of the New York Review Comics line, the abstract, absurd, and bleakly funny comic book returns, and it's just as oddly beautiful and relevant as ever.

The heroes of Agony are Amy and Jordan, a codependent couple for whom nothing seems to go right. Rudderless and adrift in a world operated by chaos and caprice, Amy and Jordan are plagued by the randomness of modern life in a farcical hellscape interpretation of a typical urban existence.

The series of trials that Jordan and Amy are put through plays like a Monty Python sketch penned by Samuel Beckett. The pair are assaulted by spear-throwing natives, attacked by a bear, locked up in prison, swallowed by cracks in the floorboards, and tormented by strange creatures. Amy is particularly marked for torture, landing in the hospital again and again. She's beheaded, eaten by a fish, stripped of her flesh, and gets an infection that swells her head so large she can't fit through the door, and when Jordan lances her head to reduce the swelling, the onrush of blood floods their apartment.

Despite its nightmare logic and funhouse twists, Agony's version of reality is at times disturbingly familiar. Amidst the bizarreness of their tribulations, there's much in the blobby, vaguely geometrical Amy and Jordan to relate to. They lose their jobs and lash out at each other. They can't stay healthy or pay their rent. Their friends are vapid and pointless, they can't relate to them, and their families are faulty support systems.

Even when good luck befalls them, everything seems to go wrong. When Jordan and Amy receive a massive amount of undeserved cash, they throw it out the window to give it away, and the ensuing frenzy results in three deaths. They're unexpectedly freed from prison, but homeless and destitute, and only released because a guard beat Amy nearly to death. Every attempt they make to escape the city and return to a simpler life ends in absurd disaster, and usually someone's death.

Like many, they're just trying to retain hope when they possess no agency and have no prospects in a world that often seems hell-bent on destroying them. And despite how much you try to fight it, that belly full of schadenfreude interprets it as mostly hilarious. Mostly...

Throughout Agony, Beyer's artwork is odd, alienating, and remarkably effective. A self-taught artist whose work could easily be classified as outsider, raw, brut, or naïve art, Beyer strikes a balance between simple, even childlike figure-work supported by a very dynamic and complex design. Beyer's flat pages ignore the laws of ratios and perspective, and yet achieve a strange sense of space and scope.

No matter what kind of environment they're in, there's an almost inescapable immensity to it; even offices and hospital rooms telescope out to infinity, making the characters feel incredibly small and insignificant. Even the panels themselves occasionally seem intent on crushing the hapless duo, squeezing in like accordions to suffocate them. And all around Amy and Jordan, spiky misshapen creatures move one-dimensionally through a world that is flat, simple, harsh, and totally unpredictable; a world shaded by dissonant textures that buzz like a chorus of dead radio stations competing for attention.

Mark Beyer's artwork is not everybody's cup, but even those who can't appreciate it can see how every pen-stroke reinforces the primary struggle of the book. It's Amy and Jordan versus existence, and like a lot of us, they're losing. - John R. Parker

http://comicsalliance.com/agony-mark-beyer-review/Most of us have at one time or another suffered from the nagging suspicion that the universe is out to get us. Or -- even worse -- that our suffering, whether brought upon by malevolent forces, just plain bad luck or random occurrence, will never end. That will always be just one damned thing after another, ad infinitum.

Which is exactly what makes Mark Beyer’s work so appealing and funny. Beyer takes that self-absorbed conceit (because, really, the basic cri de coeur of this type of angst is “why me”?) and expands it to absurd levels on the comics page, using his grotesque and at times primitive art style to create a hellish and unrelenting nightmare for his protagonists, where the basic question isn’t “will things ever get better” but “what type of misery awaits us around the corner?”

That’s the central notion, at any rate, behind Agony, Beyer’s superb graphic novel, originally published by Raw Books in 1987 and now available once again all these years later thanks to the New York Review of Books’ new comics line.

There’s no plot, per se, in Agony, just a series of hazardous events that eventually stop. The main characters, Amy and Jordan, lose their jobs, are attacked by bears and indigenous people, contract horrible diseases, end up in jail, see bad movies, are threatened, tortured, assaulted, insulted and much, much more. Not necessarily in that order.

Everything the couple does to turn their fortunes around results in more hardship. Even attempts at altruism are for naught – when Amy attempts to help others by flinging money out a window, it results in a homicidal stampede (detailed in the Mourning Call newspaper, natch).

Even death is not a reprieve from the constant stream of despair and cruelty. Early on, Amy has her head torn off by a mysterious creature, but Jordan manages to retrieve it and get it sewn back on by seemingly competent doctors. They survive horrible falls and ridiculous illnesses (at one point, Amy’s head swells up to the size of their apartment) only to revert to normal once more, ready for further punishment in the best cartoon character fashion. At times it seems as though Amy and Jordan don’t inhabit our world but some horribly punitive afterlife, forever chastised for unknown sins committed in the world of the living.

With the constant abuse and misery, it’s no wonder that Amy and Jordan occasionally give into despair or contemplate suicide (“Maybe if we’re lucky someone will strangle us in our sleep”). Hope springs eternal, however, and it’s notable that more often they attempt to convince themselves that good times can eventually be had, either by sheer luck or self-improvement. Jordan often spouts tired self-help phrases, though how much he actually believes the cliches he utters (“All we can do is to just keep trying to improve ourselves. We’ve got no other choice really.” “It’s very important that we try to make something out of our lives.”) is open to interpretation.

It’s worth noting that the lion’s share of the misery seems to fall upon Amy’s shoulders. If there’s a flesh-eating disease or homicidal maniac waiting to pounce, rest assured it will pounce on her first. It doesn’t help that Jordan is usually less than sympathetic to Amy’s plight. “I just want you to know that I don’t blame you for making us go on this trip,” he says to her at one point after she has just spent a panel vomiting blood. Upon hearing that she might suffer serious mental problems after one assault he quips, “She’s always been disoriented and mentally confused. It doesn’t sound so bad.” Whether Beyer is making a statement about the general treatment of women in America or just pushing the “Perils of Pauline” aspect of the story to the breaking point is a question I’ll leave open for debate.

Beyer is able to capture late 20th century angst and anxiety – urban or otherwise – in such pitch perfect fashion that it’s a shame he hasn’t found more places to publish or an audience more accepting of his dark comedic viewpoint. Here’s hoping the re-release of Agony Beyer affords him the opportunity to get some new comics out to the public. I’d love to see his take on our current, overly plugged-in culture. -

http://www.tcj.com/reviews/agony/

Whenever I get to thinking about the old New York City, with its cheap book marts and thriving alt-weekly trade, its surplus of less unaffordable apartments, and tolerance (or indifference) to street art that hadn’t been curated or vetted to death—in short, the turnstile-jumping bridge-and-tunnel life that began disappearing long before 9/11—I think about Mark Beyer.

At one time, many of these weeklies serialized Beyer’s cerebral, deadpan comics—especially the long-lived Amy & Jordan—before they dried up, along with the paper they were printed on. Beyer got started in 1976 when Arcade: The Comics Revue, a short-lived West Coast magazine founded by Art Spiegelman and Bill Griffith, published his first strip; his wider debut came after Arcade folded sometime later that year, in the pages of Spiegelman’s next venture, RAW, in 1980. Designed by Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly to be held and flipped through and beautifully curated, RAW was the ideal venue for Beyer’s work—a weirdo’s weirdo in profoundly weird company. Best known for introducing the world to Spiegelman’s ash-grey epic Maus, the magazine also featured Joost Swarte, Chris Ware, and Gary Panter, alongside the Boody Rogers’ bizarro Babe, Darling of the Hills, and Beyer bits like The Glass Thief (Vol. 2 No. 1: Open Wounds from the Cutting Edge of Commix), and Outside Out (Vol. 2 No. 2: Required Reading for the Post-Literate).

It is Spiegelman who attests to Beyer’s prolific obscurity: “Living in New York, it’s very easy to be skeptical about underground comix continued existence,” he told Cascade Comix Monthly back in 1979, “in a way that my compatriots in San Francisco don’t. [. . .] I think that one of the biggest problems is this thing that I just mentioned about no new blood. For instance, Mark Beyer, who, as far as I’m concerned is one of the most important third-generation cartoonists, has a very difficult time of it. He wouldn’t have if he had just been born five years sooner, but now he has a small book, he had to print it himself because none of the traditional underground publishers could handle it because of their economic situations. [. . .] The idea of a mainstream underground is a boggling one to me. I understand economically and realistically where that idea comes from, but if someone like Mark can’t find a reasonable outlet for his work, then there’s no chance for new artists to really develop.”

- Untitled Mark Beyer painting, 1978

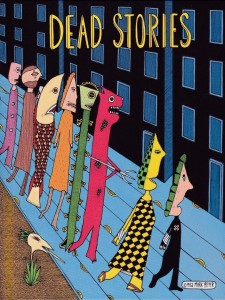

- Dead Stories by Mark Beyer, 1982

- RAW #6, 1984. Cover art by Mark Beyer (pencils/inks) and Françoise Mouly (colors)

My introduction to Beyer took place in the ‘90s by way of the meticulously self-deprecating caricatures that graced the covers of several novels published by the independent—and, now, sadly defunct—Four Walls Eight Windows press, in what still seemed in those days a truly distant New York. (I later interned there, but that’s another story.) There was Sasha Sokolov’s A School for Fools, a translation from the Russian with its Nabokov blurb (“An enchanting, tragic, and touching work.”) and decidedly un-Nabokovian rendering of two students, their butterfly net, and some very strange-looking butterflies. That book, in turn, led me to a series of novels and a collection of short stories by Michael Brodsky: Xman (1987), X in Paris (1988), *** (1994), and Southernmost and Other Stories (1996), all published by Four Walls. Like The Garden of Early Delights executed on an Etch A Sketch, Beyer’s geometric illustrations seemed to share a tortured, winking quality with Brodsky’s picaresque novels. Though the violence is always cartoonish or abstracted (Beyer has also created a line of soft dolls), there is hardly a panel or detail in which someone—or something—is not acutely suffering. Still, something about the way Beyer poses figures in profile and his nerdy, endearing style made out of that strange landscape an oddly intimate and relatable hell. Having been raised on the Great Works and Morocco-bound Classics by well-meaning parents, I was totally unprepared for something so untutored to be so effective—as well as for the realization that art could be made out of the minor materials of one’s own awkwardness by, more or less, turning one’s socks inside out to expose the raveled stitching.

- Susan Kare illustration in MacPaint 1.0, 1984

- Amy, Jordan, and bear from Mark Beyer’s Agony, 1987

Though I had come to his work late—A Disturbing Evening was self-published in 1978 and Dead Stories in 1982—what stood out, beyond the existential nightmare logic, was the way in which Beyer managed to capture all sorts of vague and interstitial states from anomie and boredom to horror and dread, with infinite shades of agony and irony in between. What I treasured most in his drawings were the contradictions, the enigmatic open-endedness, the never-ending mystery of the mundane; that Beyer resists resolution and the temptation to wrap things up neatly remains a perverse source of pleasure.

If the world we inhabit now resembles a Beyer strip, perhaps it’s because the grotesque and vulgar and irrational elements seem more in focus, while our two-dimensional discourse limps along in the background like some kind of deflated speech balloon. Health care, housing, and employment haven’t become any less precarious. The stigma around mental health hasn’t gone away. Even desk jockeys die from overwork. In The Bowing Machine (1991), which Beyer illustrated in color with text by Alan Moore, a rivalry between two salarymen—one American, one Japanese—is upended by a new machine, which adjusts the American’s posture for maximum deference. (There are panels featuring newspaper articles on the art of bowing in both English and Japanese.) Ultimately, the American rival falls victim to the performance-enhancing machine, emerging bent nearly in half, but the winner of this cynical contest by technicality. So, one might ask: is the American fortunate or unfortunate? Who should be jealous of whom? In the words of his Japanese rival, the final page is as much a rebuke of this spineless victory and America’s global influence—our, ahem, posturing in the world—as it is about the finer points of a culture that the American finds so terribly foreign and strange: “Now he has laid himself so low that I can never rise above him.”

A representative square panel of Agony (1987) depicts Beyer’s stock depressed couple, Amy and Jordan, as a stippled little pair on the road to nowhere, shaded by trees that look more like flaming pencils dwarfed by a cold, starry sky, as Jordan proclaims: “THAT’S JUST THE PROBLEM, NOTHING MEANS ANYTHING!” Another has the two surrounded by “local peasants” at the top of a hill, where the only text is Amy’s: “WHAT DOES MONEY MEAN, THOUGH? NOTHING! WE KNOW IT ONLY TOO WELL.” In his introduction to the reissue of Agony in 2016, Colson Whitehead compares this landscape to Samuel Beckett’s “absurd wastelands,” noting that, like the author of 1953’s Waiting for Godot, Beyer’s brand of despair is braided with both gallows humor and the inability to look away. Amy and Jordan are modern cognates of the tragicomic pairs in Beckett’s play: more Vladimir/Estragon (“ESTRAGON: I can’t go on like this. VLADIMIR: That’s what you think.”) than Pozzo/Lucky.

Agony, in particular, looks like something Beckett might have created if he’d been born in Bethlehem, PA, and had his comics serialized in the old New York Press. (Beyer was born in Bethlehem in 1950; Haring was born about an hour away in Reading, in 1958.) Perhaps Alasdair Gray is a better comparison: this short book is very much a product of the ‘80s, concise as it is abstract, and rendered in Beyer’s cloister-phobic, crudely flattened perspective. Amy and Jordan are back again, looking like they’ve been assembled out of common rubbish, but it’s not so much what happens to them that’s interesting—it’s their useless awareness of the ridiculous terrors still lying in wait, the suspicion that they are playthings in a grander scheme. Living in perpetual fear, constantly reacting to some new stimuli, they have little memory beyond the current atrocity. Windows and doors are erased, exits disappear. While Beyer’s innovative panel design has been noted, less remarked-upon is the way he wields vanishing point as a kind of visual non sequitur to menace the pair, pursuing his characters from page to page.

Nothing goes as planned. The usual logic does not apply. Amy and Jordan struggle to keep down jobs and liquids. They’re fired from another sinister conglomerate, the Pondox Corporation, “due to gross incompetence,” flee from “some hideous ghoul creature,” shed their skin, bicker, commiserate, escape the City, return to the City, regrow their skin, go to the movies, wonder, and cry. There’s no reason for the prolific detail, the elaborate background crosshatching and stippling involved in even the most perfunctory frames on the wall, while the protagonists in the foreground remain virtually protozoan; no reason that, after ripping off Amy’s head, the ghoul should take it to the Aquarium and dump it in a fish tank, where it’s eaten by fish. This minor masterpiece features suffering and bizarre tortures and dashed hopes, but also skyscrapers and rent checks and the odd tender moment.

Like I said, it’s a deeply relatable hell. - Daniel Elkind https://wearethemutants.com/2018/11/26/escape-from-the-pondox-corporation-mark-beyer-and-the-mystery-of-the-mundane/

Mark Beyer, Dead Stories, Water Row Press, 2000.

MARK BEYER DEAD STORIES Originally self-published by Mark Beyer in 1982 in stapled covers, offered here is the Limited Hardcover Edition published by Water Row Press in 2000. Beyer's characters Amy & Jordan face attack dogs, hateful people, sickness, death and misery as they stumble through the pages of Dead Stories - one of Mark Beyer's finest works.

see more here

Mark Beyer is a self-taught artist who began making comics in 1975. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Village Voice, and many other publications, and was a mainstay of RAW magazine. He created a series of animated shorts for MTV’s Liquid Television, designed album covers for John Zorn, and collaborated with Alan Moore. Amy and Jordan, the stars of his graphic novel Agony, were also featured in a newspaper strip that ran from 1988 to 1996, and which was collected in Amy and Jordan in 2004. His paintings and drawings have been exhibited around the world, including in Europe, Japan, and the United States.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.